THE SEMANTICS OF CHRONOTOPES

BILLY: THE SPORT

“Billy” fucked the love of my life. [1] I had known Billy for a longer time than I had known the love of my life, and that still holds true from an objective standpoint where time is universal. I knew him to be the person I was not expecting to be friends with today, not because he fucked her–because I was actually not expecting that at all–but because our friendship was extremely mild. [2] There were also haphazard and unrelated–as they pertain to each of us as friends–shared chronotopical coordinates. We happened to be at some of the same places at a lot of the same times: the concert where I met the girl I dated before I met the love of my life, the liberal arts institution in the Midwest we both attended and, finally, New York.

Understanding how memory is determined by the chronotope has always been an arduous battle between logic and emotion, because time becomes connected to the space the memory is produced in and the intensity of the experience held in each memory shapes one’s perception of time. Time may appear to no longer be measured by any watch or clock, but by the strength of one’s emotions. Space is also prone to personal subjectivity, as past memories tend to engender feelings of the past, arguments fought and wet kisses shared.

To construct an understandable narrative, the creator must give in to the limitation of linearity, regardless of how convoluted the structure of the linearity becomes. [3] As a producer of memories who also chronicles them in prose, I have often manipulated myself for days until I surrender to an objective need to stop giving in to my desire for the (re)production of an intense memory.

Last time I saw Billy we met at the Highline, [4] which is always awful and never ceases to surprise with how awful it will be over and over again. Time definitely stops forever at the Highline and the space becomes a mini-simulacrum of all that is hell: enthusiastic teenagers, people who like to document their everything for antisocial media and runners who run for fun. No wonder Billy had a freakout and cried, even if the space actually had nothing to do with it. [5]

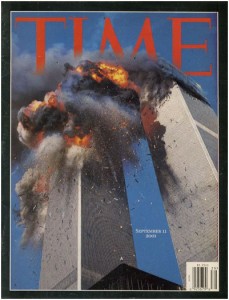

This time I was meeting Billy at a Vietnamese place in Chinatown called PHO-BANG. I go there a lot, because the wait-staff is extremely rude, but also because I like their pho and it is definitely enough for two meals, or even sometimes all the meals of a day if you get the large size with the beef chunks. My favorite detail about the kitschy exotic ambiance is the clock that is next to the counter, a clock that ticks but has stopped forever. On the clock there is a visual of the Twin Towers, a space that real time has made a non-space. I find that definitely inappropriate, but maybe I am silly to think that, especially after really loving the Tom Junod article in Esquire that beautifully conveyed the tragedy of imagery recounting the 9/11 tragedy. [6]

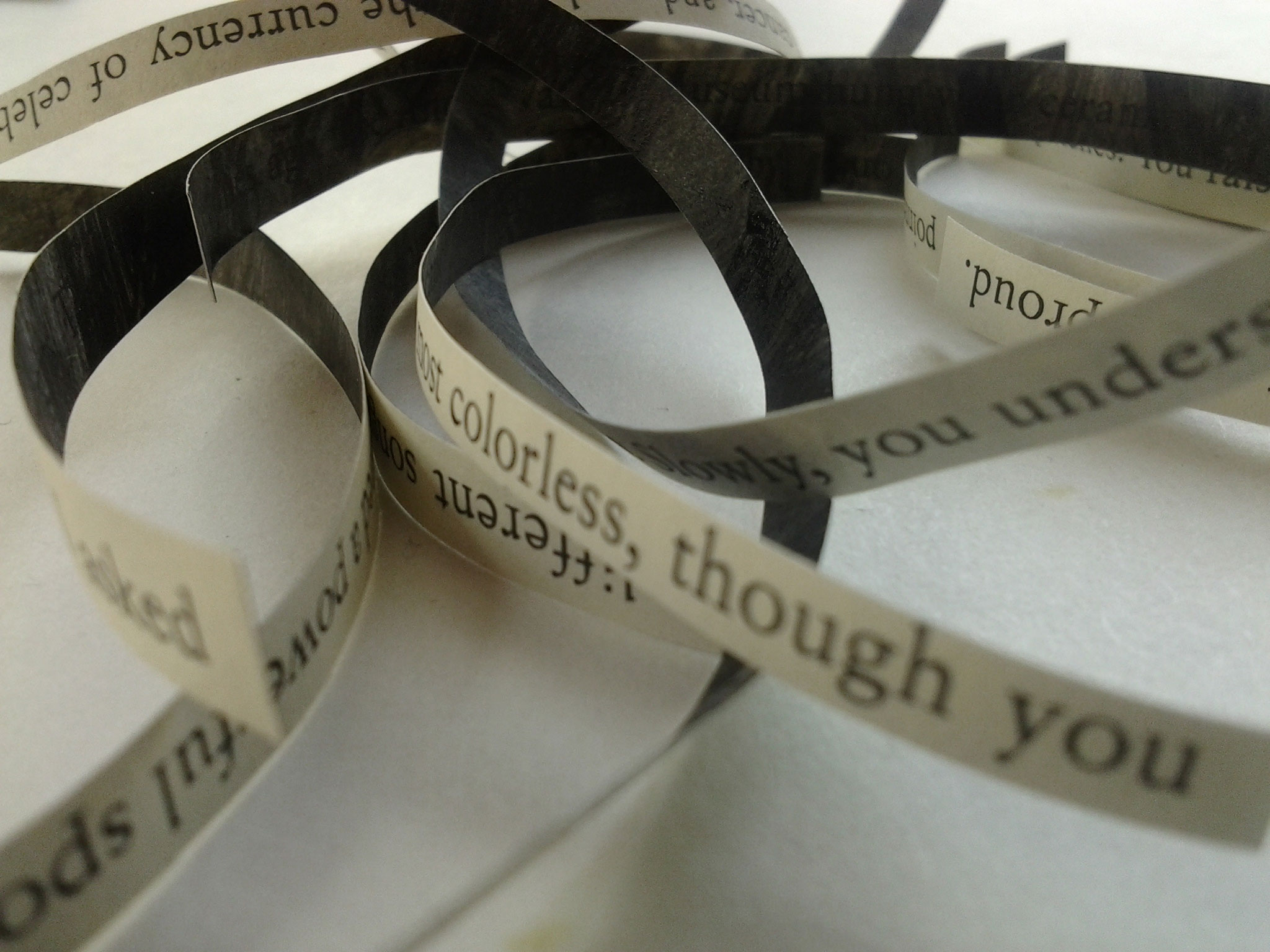

Another way to generate text #7: Gysin & Burroughs vs. Tristan Tzara

A while back, I ran a little series, “Another way to generate text.” The first one proved fairly popular, and I’ve been meaning to make more of them, but generative techniques haven’t been on my mind. However, my post last week, “Experimental fiction as principle and as genre,” generated a lot of text (haha), in the form of comments. Some people who chimed in questioned whether the Cut-Up Technique that Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs developed and used in the 1950s was ever all that experimental. Specifically, PedestrianX wrote:

I find it hard to accept this argument when its main example, the Cut-up, didn’t start when you’re claiming it did. I’m sure you know Tzara was doing it in the 20s, and Burroughs himself has pointed to predecessors like “The Waste Land.” Eliot may not have been literally cutting and pasting, but Tzara was.

This comment got me thinking about the role influence plays in experimentation; more about that next week. Today I want to address the point PedestrianX is making, as it strikes me as pretty interesting. Were Gysin and Burroughs merely repeating Tzara? Or were they doing something substantially different?

To figure that out, I decided to run through the respective techniques, documenting what happened along the way. Because if I’ve learned anything in my studies of experimental art, it’s that thinking about the techniques is usually no substitute for sitting down and getting one’s hands dirty.

If you want to get dirty, too, then kindly join me after the jump . . .

being tired, being inspired

I came across this gem last night while I was not sleeping. I’m particularly interested in Mr. Tate’s idea of “writing out of exhaustion” — that writing while tired (either physically or mentally, I guess) can result in material interestingly distinct from writing written while one is “refreshed.” This seems to be the polar opposite of what Maggie Nelson expresses here (via here) — that periods of inactivity are somehow inherent or necessary to periods of activity. I don’t know… I feel like I see the merits of both. There are times when I’m particularly energized and times when I’m not, but I like to write through it all. How bout you guys: write to exhaustion or write through exhaustion? THOUGHTS?

lunar methodist 4

5. Willows Wept Review redux.

9.

Dear Darth Vader,

Vader, I love you & think you are a total badass, but when you lost Padme and yelled NOOO! Yah, that was super lame. You are supposed to be a person filled with anger & evil, not love and compassion. You really let me down with that NO. In fact, you did not only let me down, but you let all of us down, all of us Star Wars fans. Next time, be a little bit more of an evil badass, not a pretty princess.

Yours Truly, Simón Gutkin

4. An odd and lovely collection of facial expressions in literature.

Face had fallen like a waffle —Frank O’Hara

A gentle, cowlike expression passed over her face like a cloud –Colette

Had a face like a requiem —Honoré de Balzac