In the Moremarrow / En la masmédula by Oliverio Girondo

In the Moremarrow / En la masmédula

In the Moremarrow / En la masmédula

by Oliverio Girondo, translated by Molly Weigel

Action Books, 2013

93 pages / $16 Buy from Action Books or SPD

the mix

yes

the mix I stuck my bridges together with

That first line is beautiful & on one level it seems a sort of how-I-wrote-my-book-and-so-can-you! treatise by Girondo. They are the last 4 lines of In the Moremarrow‘s first poem, The Mix

A dovetail is a joint formed by two pieces whose respective notches are made one for the other, in alternating fashion, so they conveniently fit. Here, the dovetails are undone, & instead we have for example soulmortar, an unlikely union of the ethereal intangible but vital, with the crushed inert material. Which, in creation myths, sounds like the soul blown into dust to animate a person. Perhaps, then, this is not so foreign. It is more primordial marrow. The mix seems to refer, then, to this poetics of uniting the disjointed, of mending broken ligaments, & the “bridges” are the compound words themselves, the neologistic portmanteaus

It is hard to say what stubborn female couplings refers to. Maybe something about the male poet accepting his anima, that female part of him that is stubbornly there but his machismo stubbornly rejects. This is a reach, as psychoanalysis is a reach. The “ex-she” seems to support it, & the several later poems’ repeated references to the ego seem to support it, & the erotics of “the mix” seem to support it, but it still feels like conjecture

Every left page gives the original Spanish version of the poem, and the right page holds the translation. I notice the Spanish helps. The original version of that first line is two

la pura impura mezcla que me merma los machimbres el almamasa tensa las tercas

hembras tuercas

English grammar now is largely gender-neutral, and Spanish grammar isn’t. Every noun & adjective in this sentence is female (ending in -a or -as) except for two. On a macro level we at least can say that “female couplings” refers to the writing itself. The writing is self-referential. The universe of En la masmédula writes its own rules & thereby writes itself into existence. Perhaps this explains its lack of proper nouns; on one level, it has no need to tie itself to the World as we know it, it needn’t be referential, it loves itself into being, it is self-reverential. It ties itself to the Word. It hermetically seals itself

But on another level, no. It hermaphroditically seals itself

Because it rewrites itself by correcting the mistakes of our World. The mistakes of our World embed themselves inside the grammar that we use, those stubborn couplings that lead us towards fixed fragmentations, binary perspectives, formal & social discriminations. Therefore the recombinations in this book are all still legible, because they adhere to grammar rules but comment on them while deforming them. “alma” for example means soul. It is one of those strange nouns with a feminine ending (alma), but is nevertheless considered a masculine noun, hence the male article “el.” Combining “alma” with the feminine noun “masa,” however, creates a Word of indeterminate gender, but the “el” still precedes it. This seems a problematization. “masa,” in fact, means flour, it is the baseline substance for sweet sumptuous cakes, for savory bread of the Earth, etc.

“machimbres” isn’t a word. It reminds of the word “machismo,” a word English has imported, & of the word “chimba” which can mean the opposite bank of a river, or a pigtail, or a piece of meat, etc. It also sounds like “machihembrado,” a dovetail joint, hence Weigel’s translation choice. It seems again though that this dovetail has been pared down, to remind us of all its assemblage, & question gender once again. To undo the dovetails, quite literally. A beautiful translation choice. It bridges shores. The shores Girondo sticks his bridges with

Translation is hard.

*

solicroak

prefugues

sighspirits

selfsoundings

inlabyrinth

ex-she’s

soulmortar

*

A lot of poems end on their own titles, creating a feeling of being in an enclosure. This is a bizarre feeling, because the poems are intensely lyrical without being confessional or “sincere” or narrative in the way the Lyric I often attempts to be; instead it is like handling a ball of pure psychic energy. The poem entitled “You have to look for it” has three stanzas, each of which ends on “for the poem,” which inscribes itself within the title’s “it.” The first line of the poem goes

In the eropsychis full of guests then meanders of waiting absence

Which is, like, incredible. But once again, very gestural. It once again informs the readers of the poem’s motive & the poem’s dimensions. It is a meeting place, a delimited house, a hovel of guests, entering the poet’s eroticized ego; it couples. There are other people there, straying, erranding

January 31st, 2014 / 10:00 am

A Room in the Living Ruin of the Lyric

Hosni Mubarak

Hosni Mubarak

by Jared Joseph

Persistent Editions, June 2013

35 pages / $8 Buy from Persistent Editions

Hosni Mubarak is author Jared Joseph’s second chapbook of poetry, and Persistent Editions’ inaugural publication. Mubarak’s lyric-challenging poetic establishes Joseph and Persistent Editions as poet and press to be followed.

What strikes first about this collection is its cover: a photo of Mubarak from the shoulders up, his faced streaked in neon reds, yellows, and blues. We know straight off that we are in potentially provocative territory. When the critical reaction to Carolyn Forche’s The Colonel remains today as a reminder not to vacation in the suffering of others, it might seem that a book – written by an American – that takes the name of a deposed Egyptian president might be waiting for the same charges to be levied against it. Not so. What we have here is a different entity entirely.

Here, the emotional counterparts (see: apathy, detachment, disillusionment) to Western media-era remove from world events are not elided; instead they provide the bridges that Joseph uses to write into his encounters with “Mubarak”. Yet Joseph is able to do this without twisting the work to become pedantic – there is no claim to a better perspective, no call for empathy or action other than what might be suggested by its lack. Joseph moves in and out of autobiographical modes through the eyes of this imaginary Mubarak: these qualities are explored in Mubarak, and in the speaker inside Mubarak. This is not a convenient mirror in which to better see ourselves – this is the light across it, the shimmer of something just behind our shoulders, and the language is its play.

The voice of Joseph’s Mubarak is at once erudite and childlike: language not used exactly, but capably, as if itself exempt from a pressure to be dutiful – it phrases the world as it pleases. The speaker shifts fluidly, almost arrogantly, between lexicons: the scientist’s, the politician’s, a young man’s – shifting code and binding vocabularies together, and in the process enacting a wild sense of entitlement:

a tension reservoir of air, something requiring the first exhale-

ation, I don’t really understand natural laws. Anyways, just

one finger needed to fire empty the casing.

July 12th, 2013 / 11:00 am

25¢ CASH

25¢ CASH

25¢ CASH

by Jerimee Bloemeke

Slim Princess Holdings, 2013

36 pages / Book page

scramble all the codes

and transmit the decoded flows of desire

starts the poem that starts the book, a quote I recognize from Deleuze & Guattari talking schizophrenia & capitalism in Capitalism & Schizophrenia. So we have an initiating coded imperative in sleek italics that distances the writer from himself & from the rest of the text, establishing a poetry as somewhat schizoid. That state where – perhaps because of the self’s dissociation from it-self – all interaction is associative, a total empathy with everything.We don’t have a hierarchical root system so much as an omnidirectional rhizome system where every word’s a bud, or a bud-world that only grows Possibles. In Wisconsin I had a schizophrenic friend-acquaintance named Cosmo who often visited me at work & called me Honey Bear. I don’t believe in romanticizing schizophrenia because Cosmo died early. But I do remember Cosmo was funny, a brilliant presence, a musician & a painter, & he owned a sort of honesty & clarity that only a very heightened state affords, when one is able (when one is solely conditioned) to live in a world of code dripped off, to speak in what is not so much a code as it is the very scramble that we as writers often seek to perform, to – by way of breaking down the known code – transmit a very resonating, viscerally familiar one, a primal blood code. It is this distance that allows a return to something closer, something primary:

where they are hiding / with a rubber gloved hand

This is strange to me because each poem, usually, is a line-broken, fairly uniform block of text, so what are these slashes doing? They occur often in this poem & throughout the book. I think they must be a realization of this self-directed (& perhaps reader-directing) injunction to scramble the codes or the straightforwardness (which is funny to make synonymous, code = straightforwardness) in order to let out our outward flows of desire. It is as if what we think of as whole, is actually a mosaic of fragments & dissections based on our minds’ subconscious reconfigurations; here, instead, the whole cohesive discovers its part. If I could see every shard of my desire I would go crazy, I know this, with the same whole love I carve into every face I see every day, I call everyone unique to myself, serially. “where are they hiding” is funny, as if a hiding place isn’t a sort of code itself, “with a rubber gloved hand” sounds beautiful to me because it’s as if these codes wear surgeon’s gloves, deeply impersonal sterilized coverings in order to more profoundly enter & probe around. On the one hand it is like fucking a condom. On the other hand, without that distancing interface, it is hard to otherwise love & meet.

chauffering and he wouldn’t tell us and rolled up

his window (and we saw who we were ourselves)

I think this part is kind of amazing because, for one thing, the language seems so effortless. But also it is that asking of a person “Who are you” which results in a verbal covering & defensive maneuver, an immediate ostensible refusal of traditional self-identification; but then it effects a physical approach, a rolling up that is both as of blinds rolling up & as of wheels circulating in order to move forward. It’s a strange thing about cars that’s explored here in this book often.

May 3rd, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Commuting: Have gone to Ithaca – Frank Quitely

Commuting: Have gone to Ithaca – Frank Quitely

Commuting: Have gone to Ithaca – Frank Quitely

by Jared Joseph

TRNSFR / Varmint Armature Press, 2012

40 pages / $6 Buy from TRNSFR

This is a review of Commuting: Have gone to Ithaca – Frank Quitely by Jared Joseph, which is the third Chapbook from Alban Fischer and TRNSFR’s newish book arm Varmint Armature Press.

[Watch the Book Trailer here: Commuting: Have Gone to Ithaca. -Frank Quitely]

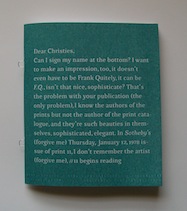

The title introduces the collection as a persona poem. Frank Quitely is the narrator. Frank Quitely is the clever inversion of “Quite Frankly”. The Frank of this work emerges in the title as a person making the journey to work. Frank is commuting to Mythical Ithaca. Everyone needs a commute, and Frank is no different. Frank Quitely is or wants to be the author of print catalogues for auction houses dealing in art like Sotheby’s and Christie’s. In the cover letter that opens the collection Frank asks Christie’s for some recognition as the one “who has wroughted”. This author character Frank is conflated and conflicted with the identity of the Jared Joseph, whose name intrudes upon the world of Frank in moments of Frankness or weakness. In Frank’s despair the world of the print catalogue collapses, and he wonders whether or not there are catalogues or prints inside them or if these are “just” poems or epigraphs to imagined pictures.

August 3rd, 2012 / 12:00 pm