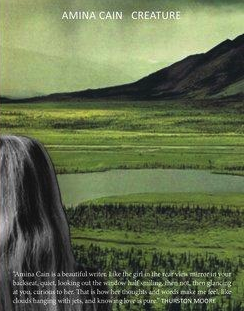

I write to see what is inside my mind: An Interview with Amina Cain

“I’m not sure why I’ve written so many flat male characters. I think it’s more that I have wanted to pay attention to the female characters and so I have.”

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

***

LW: When did you start writing?

AC: I began writing during my last year of college. I started out as an acting major, which I quickly gave up, switching to Women’s Studies. I knew I wouldn’t necessarily do anything specific with this major, but I was interested in the classes. Then, when I took my first creative writing workshop, I knew I had found what I wanted to do with my life.

from the film adaptation of Hour of the Star

There are many references to Clarice Lispector in your work and in your story Queen you quote from The Hour of The Star: “forgive me if I add something more about myself since my identity is not very clear, and when I write I find that I possess a destiny. Who has not asked himself at one time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?” When did you first discover Clarice Lispector? Would you say you connect similarly to her themes of the metaphysical experience of “finding yourself” through the process of writing?

I relate very much to the idea of finding oneself through writing, though what “oneself” is I think is malleable. And that Buddhist idea that to study the self is to find the self and to find the self is to lose the self resonates a lot for me. I’ve been curious lately about why I am so driven to write first person narratives (that are both not me and me) as opposed to third person, for instance. It’s not that I want to tell a story of myself, or even of another, it’s that I want to inhabit something—some feeling, some space (physical or psychic, and yes, even just the space of writing), or voice, and the first person, for whatever reasons, allows me to do this in the strongest way. I certainly think that Lispector’s fiction does this too, much more so than simply telling a story. She creates these charged psychic spaces we can walk into as readers. I first read Lispector the second time I lived in Chicago. I checked out from the library Family Ties, a collection of short stories. Then The Hour of the Star.

So many of your stories seem to be about a central narrator. They can be separate and yet they feel a part of a continuous story. Can you talk about the narrator of your stories? Do you consider her a persona? Do you see her as existing in each of your stories? Or is she different, a new character, each time?

I see the narrators in Creature as different beings but as sharing a single heartbeat. I wanted them to be both separate and connected. In Tisa Bryant’s amazing Unexplained Presence a beautiful continuum comes into being, or else a soft light is shone on connections already present between people who existed throughout time but never knew each other, or even knew to know each other. I was so struck by that when I first read Bryant’s book, and I think the idea of the continuum has stayed with me since, though of course in a different way.

There is a quality of bleakness to your characters, or to quote from one of your titles, “a threadless way” about them. They are very honest about the fact that they don’t know what they are doing or how to connect to others. (And yet, because of this, they do know—like what you were saying about finding the self to lose the self, etc.)

This is a sharp contrast to what we are used to seeing in a lot of contemporary literature. (Of course, “flawed characters” are everywhere—but usually they don’t know they are flawed and when they do, their revelation is fleeting or they step into denial.) Your characters have the ability to speak, feel, and live out their insecurities, distastes, annoyances, melancholy, and this gives them a strange hopefulness and positivity.

I think that most of my characters are searching for something, are always in process with the world around them, and that much of what gets expressed in the stories are the things that are usually not said, supposed to be said, voiced. In fiction, I’m as interested in an inner life as an outer one, and I want to write that life. I think it can propel a narrative forward as much as plot can. There is drama there, and conflict, and relationship, and even setting. I’m glad that the characters feel hopeful to you. Sometimes there is a focus on the sadness and vulnerability in my stories, elements that are certainly present, but to me there is also absurdity and humor. READ MORE >

The Strickland Dildo

Guest post by Emma Needleman

I.

The other day, I clicked a link to an essay called The Zambreno Doll, a prose poem by Garett Strickland. The essay—apparently inspired by the experience of Kate Zambreno unfriending him on Facebook—disgusted me. In it, Strickland accuses Zambreno of deliberately “occluding” him on the basis that he’s a white male, speculates that she needs to hatefucked by a real misogynist, and gleefully fantasizes about turning her into a doll.

Reading the piece infuriated me. I’m tired of seeing women I respect get treated like this. It made me so angry that I broke my New Year’s resolution to stop fighting with people on the Internet, and I left a series of comments calling Strickland a “dweeb” and a “loser.” I would like to take the opportunity to say that I stand by these statements. Later, I wrote longer comments calling attention to the gender dynamics of Strickland’s piece, and I also stand by these statements, although not to the same degree as my original assertions that he is a dweeb.

Garett wrote comments, too. They said things like:

“Ah yes right. Forgot I’m a man. Just a man. Not a person or a human or a life, but a man. Just a man. Way to put me in my place!”

“I just looked up the definition of misogyny to make sure. No, I don’t hate women. So I wouldn’t consider [my piece] misogynistic.”

“I find all this cultural obsession with gender objectionable to the point of boredom.”

“Rather than simply keep my mouth shut regarding my opinions—or ghettoizing those opinions to conversations where I can make certain I’m only being agreed with, a la Zambreno—I’ve decided to share them out of an obligation I feel toward radical openness.”

::: :::

Like Strickland, I’m writing this piece because of an obligation I feel towards radical openness. I don’t want to restrict my conversation to places where I know my opinions will be agreed with, like among Mr. Strickland’s ex-girlfriends. That’s why I wanted to write The Strickland Dildo. It’s an exploration of the cultural forces that enable things like The Zambreno Doll to exist.

II.

Garett Strickland looks exactly how I would expect him to. His author photo shows him slumped in a chair, holding a (fake?) gun and looking stoned. He looks like ninety percent of my male friends: scruffy hipsters who earnestly think that people want to hear about their taste in music, dudes who smoke weed all day, and insist that being 1/16 Native American means they’re not “really” white.

I Google him and instantly regret it. It’s exactly what he wants me to do.

::: :::

The evening after The Zambreno Doll is published, my doorbell rings. When I open it, I see that a small, brown package has appeared on the porch. Could it be? The Strickland dildo? The phallus itself?

I bring the package inside quickly. If it’s the dildo, I already know what I’m going to do with it: take mocking photos of it and post them online. I have a whole series planned out. First, I’ll get my prettiest girlfriends to hold it up and make a face like they’re going to be sick. Then I’ll put a little Santa hat on top of it. Finally, I’ll feed it to my neighbor’s dog.

I tear open the package but find no phallus. Insteadi, it’s a set of twelve toy soldiers, the old-fashioned metal kind. I’m disappointed. I didn’t ask for these. I wanted a doll, or its equivalent. Why should Garett get one and not me?

But I know why. Because he’s had it all along. Because he didn’t have to ask. Tears fill my eyes. This is confirmation of a terrible reality.

::: :::

Lately, I’ve been sitting in on an undergraduate class on 19th century German philosophy. The class begins with Kant and concludes with Nietzsche’s On The Genealogy of Morality. I like Nietzsche, maybe more than I care to admit. I certainly like him more than anyone else in the class, even though the other people in the class are all twenty-year-old boys, and twenty-year-old boys have historically been Nietzsche’s primary audience.

I like Nietzsche because he understands cruelty. He knows that we need to be cruel and that we need to know that we are cruel. If we don’t see the pain on the Other’s face, we will destroy ourselves. I believe this is true.

But I don’t think that this paradigm applies to Garett, who just wanted to “put Kate in her place”—to make her feel bad so he could feel powerful. He felt so entitled to that power that he became angry when she exercised even the tiniest bit of agency. He implied that she needed to be hurt, that she needed him to hurt her. That’s why I’m comfortable writing things like, “cry harder, dweebus” or “your dick is gross and bad.”

::: :::

After a few days, I take out the toy soldiers again. Maybe I can do something with them—give them to a thrift store or homeless shelter. I open the box and notice that the soldiers look different, somehow. I squint and lean closer. Suddenly, I realize what it is: each of them has a distinct and highly detailed face. How did I not see it before?

I pick one up and examine it. It’s Garett Strickland. I pick up another one. It’s Sigmund Freud. I pick up another one. It’s the kid from my writing workshop who only wrote stories about women getting murdered. I pick up another one. It’s the man who grabbed my ass the first time I rode the subway by myself.

By now, my heart is pounding. I check the rest of the soldiers and confirm: yes, I recognize all of them. Yes, yes, they’re all here. It’s time. It’s finally time. I know what I have to do.

I go into my bedroom and put on my hiking boots. Then I line up the metal soldiers in two neat rows and crush each one under my feet. Like I said before, I find this cultural obsession with masculinity objectionable to the point of boredom.

OPEN LETTER TO HTMLGIANT: THE SEXISM STOPS HERE

I think everyone has an Internet feud they will never forget. Here’s mine: in January 2010, Jimmy Chen wrote a post for your site (that has since been removed) in which he showed a photograph of Zelda Fitzgerald and “complimented” her cute rolls of back fat. In the comments section, I called out the sexist move of reducing a female writer to the shape of her body, and was immediately dismissed with a “fuck you” and someone asking why I had a sexy picture of myself on my own blog.

And on my blog, Chen told me my life would be easier because my face looks like this.

In an open letter apology (that has also since been taken down), he wrote, in his defense:

“Leah [sic] Stein has a ‘right’ to post a sexy picture of her, and I have a ‘right’ to think her life will be easier because of her beauty than an ugly woman’s which is why she [sub]consciously posted it.”

There is nothing easy about the life of a writer with the face of a woman, especially when men get to tell you what you’re allowed to do with your face. Which brings me to yesterday’s post by Garett Strickland, about how Kate Zambreno humiliated him when she unfriended him on Facebook, taking away his ability “to participate in a conversation I’ve got as much right to as any other human being, regardless of the seemingness of my being white or male.”

Note that both Chen and Strickland are eager to point out their “right” to write whatever hateful, sexist, ignorant thoughts cross their minds, even in the personal spheres that female writers are often forced to create out of necessity for their own safety (Chen was commenting on my blog; Strickland was writing on Kate’s own Facebook page).

In retaliation for his hurt feelings, Strickland goes on to unleash what I can most accurately call a sloppy prose poem about sexual inadequacy, which ultimately turns Zambreno into a doll, “Made by Men,” who arrives in a box. When he pulls the string, she delivers “reactionary polemic” that Strickland can’t understand due to “personal deficiencies.”

Here’s the most significant thing Strickland doesn’t understand, the worst of his personal deficiencies: he doesn’t realize that by objectifying Zambreno and turning her into a doll, he is being aggressively chauvinist. He isn’t participating in a conversation he has a “right” to. Notably, in order to have a conversation, he has had to create a doll who can only spew pre-recorded messages, who can’t actually talk back.

To Chen and Strickland, I would ask: have you ever been reduced to a body and a face? Have you ever felt afraid for your safety because of your body? Has anyone ever trivialized your work because of your gender?

In the summer of 2011, I met with a team of Random House sales reps who would be responsible for bringing my novel and poetry collection to bookstores and libraries around the country. One asked me what kind of cover image I wanted for my novel.

“I only know I don’t want a headless woman on the cover,” I said. “I don’t want my book cover to exclude men from picking it up.”

“Do you really think a man would read your work?”

“Well, a lot of men like my poetry,” I said.

“Only because you’re cute,” I was told. By my editor.

I didn’t know what to say. I like to think that out of the 37 people in the world who read poetry, the men who read mine are finding some merit there, and not just jacking off to my author photo.

Chen has described Zambreno as “a feminist who hosts an irrational hatred of me due to not being able to perceive my misogyny ironically,” but what’s truly ironic in all this is that Zambreno has written an entire book about women who were written off, robbed, and institutionalized for/because of their creative talent, while their husbands and lovers were celebrated. I read Heroines with my jaw hanging open in recognition, especially when I got to page 140. She describes Chen’s Zelda post and the feuding in the comments section:

The snarky dismissal. I answer back with vitriol. It becomes heated, ugly. Personal. Slurs of a sexual nature slung in the comments section, mostly by a chauvinistic supporter of Chen’s. A way to bully, which is to humiliate, to silence, to make a woman smaller whose behavior is seen as outsized. (Won’t she fucking shut up?)

As writers, we know words carry power. I challenge HTMLGIANT contributors to use their power to make this site the weird-ass literary carnival it is at its best, without using discriminatory, sexist, hate speech that objectifies, humiliates, and infuriates their female readership. To quote the Urban Dictionary, please check yourself before you wreck yourself:

Take a step back and examine your actions, because you are in a potentially dangerous or sticky situation that could get bad very easily.

Sincerely,

Leigh Stein

The Embrace of Impurity

Eva Hesse - Hang Up, 1966

THE ZERO-DEGREE NOISELESSNESS OF DEATH: LECTIO I-IV

Speech may be a function of Logos, where rational compositions serve as cultural appropriation, or speech may serve a revolutionary, contestatory role by internally rupturing the structures of Logos at the very points of its own contradictions; screams and laughter may be reactive phenomena, resulting from the neurotic exigencies of life, or they may serve serve as rebellious eruptions of corporeal energy, heterogeneous outbursts of expropriation, where Logos is disrupted by the libido; silence may be the zero-degree noiselessness of death, where life itself is betrayed, or silence may be that moment where sovereignty is elliptically expressed as incommunicable inner experience.

In Medieval philosophy and theology, a lectio (literally, a “reading”) is a meditation on a particular text that can serve as a jumping-off point for further ideas. Traditionally the texts were scriptural, and the lectio would be delivered orally akin to a modern-day lecture; the lectio could also vary in form from shorter more informal meditations (lectio brevior) to more elaborate textual exegeses (lectio difficilior).

LECTIO I: Kate Zambreno’s Green Girl

LECTIO II: Horror vs. The Patriarchy

LECTIO III: Joe Wenderoth pushes the surface

LECTIO IV: The Dionysian Excess of Living

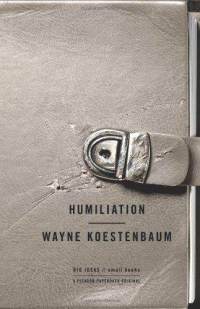

Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation & Kate Zambreno’s Green Girl

Just released from Picador’s “BIG IDEAS // small books” series is Wayne Koestenbaum’s 184 pp meditation on Humiliation, which I read in two 2-hour sits on a stationary bike punctuated with a few seatings on the toilet. It felt good to read this book in those places, which is often where I read anyway but don’t as often get to admit with relevance, but at last, here is a book in which those sorts of places might well be the center.

Just released from Picador’s “BIG IDEAS // small books” series is Wayne Koestenbaum’s 184 pp meditation on Humiliation, which I read in two 2-hour sits on a stationary bike punctuated with a few seatings on the toilet. It felt good to read this book in those places, which is often where I read anyway but don’t as often get to admit with relevance, but at last, here is a book in which those sorts of places might well be the center.

Humiliation operates in many ways at once. In short, numbered sections referred to as “fugues,” themselves cut up into numbered chunks of information, Koestenbaum goes forth into dissecting how the experience of being humiliated operates on a person, and therefore creation. The span of references here are quite wide, revolving quick enough to keep the brain moving as quickly as Kostenbaum’s dissective eye wakes each one up. From craigslist ads such as “HAIRY ITALIAN WANTS TO HUMILIATE A GENEROUS BITCH,” to Koestenbaum’s lurking in men’s rooms for encounters (and politicians caught inside the same), to de Sade and Artaud and Basquiat and Michael Jackson, and so on, the feed remains continuously engrossing in that way that all acts of humiliation seem to, publicly and privately, in spectacle, though here handled through Koestenbaum’s sharp and self-aware way of parsing act into idea.

“The reason I’m writing is to silence the deep sea-swell of my humiliated prehistory,” Koestenbaum writes, “a prologue no more unsettling than yours.” One of the major ideas explored here seems the matter of identity and experience that arises from the very act we work as people most ways to avoid: being humiliated. In each transaction there is the victim, the abuser, and the witness. Koestenbaum pulls off this weird shift of internal self-creation mixed with the experience of the other in an incredibly balanced method of veering back and forth between cultural commodity, confessional remembrance, and pointed commentary. A lot of questions are asked, moments are raised, allowing a kind of skin to rise up rather than some definitive proclamation of the idea. The book itself seems to both reveal and reveal and turn and turn, the way we might try to pretend to not be looking at something in the presence of someone else, though unable to fully look away. The moments of the facing, too, are powerful for how plainly they’ve been laid out. The book ends with a list in the spirit of Dodie Bellamy of some of Koestenbaum’s humiliating experiences: “My mother pulled a knife on my father, whose shocked aunt sat watching on a black leather chair. (The knife had a dull blade.)” or “A kid in seventh-grade gym, on the soccer field, called me a ‘wop faggot.’ I was flattered to be mistaken for an Italian.” The chain of small hells is both cringey, silently grinning, desperate, and wise. These things are laid out for us to take them, and this too becomes part of the machine, a kind of revolving door of do what you will with this, and please be kind. That at the same time Koestenbaum bares such skin he makes his subject so impossibly addictively paced and by turns tickling that it is impossible to put down becomes both a welcoming and a silent stab of implication: we are right here and he can’t see us and we can see all of this of him, which is the nature of the transaction of all making, and all taking. READ MORE >

Channeling the Alien-Plath Girl: Emotional Drag/Porn/Excess

I heard Dodie Bellamy use the terms “emotional porn” and “operatic suffering” recently on her blog and I love that. I recently wrote on my blog about “emotional excess” in relation to the films of Andrzej Żuławski, and I’ve just been thinking–I love things that are flamboyantly and unapologetically emotional. It makes me think of teenagers. Since crossing over into my 20s, I look at teenagers and feel kind of embarrassed for them. They lack emotional filters. They’re so direct about their suffering. They’re making themselves look pathetic. But really–I kind of envy them, their lack of restraint. It must be really freeing to be that open without feeling the urge to censor yourself.

When I was in high school, I used to call a certain type of girl a “Plath Girl.” For me, the Plath Girl was white, upper-middle class, educated, a perfectionist, melodramatic, mean, and incapable of feeling joy. I guess I still used this term in college…isn’t that fucked up? This is my therapeutic admission of my fucked-upness. Yes, now I remember. There was a girl I thought was cute and I asked her on a date. She always wore black eyeliner and had a Virginia Woolf tattoo. I thought we could go to the airport and watch the planes take off but she was like, why don’t you just come to my room? When I went to her room, she did lines of coke off her desk while ranting about how much she hated everyone, how depressed she was at school, and before I knew it, she had left me so she could hang with other people. When my friends asked me about the date, I think I just said, “turns out she’s quite the Plath Girl.” (But was this an incorrect categorization? Did the tattoo mean she was actually a Woolf Girl?) Really, I think the Plath Girl is kind of sexy. She has direct access to her emotions and isn’t ashamed to show her bitterness or depression. (I am also involuntarily turned on by emotionally volatile people that can sometimes be cold to me. Perhaps it is a masochistic impulse.) There is certainly a performative element that pervades this kind of outward display of emotion, but that doesn’t mean it’s just some stupid act.

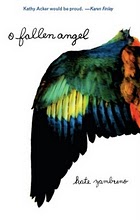

Win Kate Zambreno’s O Fallen Angel

The wonderful Kate Zambreno has offered to give three copies of her book O Fallen Angel to HTMLGIANT readers. In our recent interview with her Kate said:

The wonderful Kate Zambreno has offered to give three copies of her book O Fallen Angel to HTMLGIANT readers. In our recent interview with her Kate said:

“I had these three characters haunting me—Maggie is in many ways a grotesque carciature of another character I had written before, Ruth in an unpublished novel Green Girl, a sort of postfeminist libertine who’s also quite passive and tragic, sort of like if a Jean Rhys heroine was alive now or Clarice Lispector’s Macabea.”

As such, we’d like to hear about your inspirations, or stealings. Comment with a brief confession of something you’ve manipulated or stolen, language-wise or other. Kate will pick three winners sometime late Wednesday.

[Also, this week a new limited edition and only briefly available piece from Kate has been published by Legacy Pictures: I AM SHARON TATE.]

Some Books I Loved Recently and Hope to Write About Soon

I got laid off! It’s awesome (seriously, it’s kind of good news). I have to work till the end of the year and then: the future!

I got laid off! It’s awesome (seriously, it’s kind of good news). I have to work till the end of the year and then: the future!

Since I’m feeling so positive, I want to list some books I read recently and loved. My mom would call this “a lick and a promise,” which, now that I think about it, is kind of gross. Can someone tell me what is a lick and a promise? Mom would say it when she only wanted me to do a fast job of cleaning up the living room with the intention of doing a better job later, as I intend to do with these book thoughts about Killing Kanoko, When You Say One Thing But Mean Your Mother, Ten Walks/Two Talks, Poetry! Poetry! Poetry!, The Irrationalist, and O Fallen Angel, below the fold. READ MORE >

May 12th, 2010 / 12:45 pm

Murderous Fucking Murderous: An Interview with Kate Zambreno

Kate Zambreno go es for the throat. Or at least her language does, in the manner of those who came to wreck not by demanding, but by will. Her debut novel, O Fallen Angel, (which won the Chiasmus Press ‘Undoing the Novel’ contest) arrives in the grand spirit of Acker, Artaud, Burroughs, but where these are A and A and B, Kate is Z in full: her own, slick, squealy, and of another light. As well: Fun, funny, fucked, freaklit, surprising, terrifying, gorgeous. Her words are a meat we surely want more of, quickly.

es for the throat. Or at least her language does, in the manner of those who came to wreck not by demanding, but by will. Her debut novel, O Fallen Angel, (which won the Chiasmus Press ‘Undoing the Novel’ contest) arrives in the grand spirit of Acker, Artaud, Burroughs, but where these are A and A and B, Kate is Z in full: her own, slick, squealy, and of another light. As well: Fun, funny, fucked, freaklit, surprising, terrifying, gorgeous. Her words are a meat we surely want more of, quickly.

On the event of her book’s release (which you can pick up now through SPD) (and read an excerpt of at The Collagist) (and see read live in Chicago this Saturday at Quimby’s), Kate and I spent some time discussing via email her new book, her influences, art, language, terror, cliches, Playboy, Bacon, body fluids, and all things therein.

* * *

BB: The copy of the back of O Fallen Angel says it was inspired by Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. The images in that painting are quite striking, esp. in that I didn’t look it up until after the text. The orange and white contrast, with the odd body shapes on pedestals as if vivisected and mutated bits of humans stuck on gross smooth forms really resonated in retrospect with the three rotating voices of your text, and made me realize a lot about it in seeing, applying the imagery to the residual effect of your words. I wonder if you could talk about how that image struck you as a way of opening the door here, what effect it had in a process sense, and perhaps how it continued to inform the structure or tone of the book.

Kate Zambreno: I’ve been really haunted by that triptych. For a while I lived in London, really when I first started writing I worked in fiction at Foyle’s bookshop and read all of this experimental fiction for the first time—Ann Quin and Elfriede Jelinek and all the Peter Owen books, Jane Bowles, Anna Kavan—and ran the cult fiction section. I would go to the Tate Museums to the Francis Bacon room in the Tate Britain where they had that first major triptych. I worshipped and gawked at that first triptych, that orange gruesome horror it filled me with such violence and ecstasy. Those three gruesome distorted bodies, the open mouths in Bacon, the silent scream. I’m really interested in the silent scream how we are muted in society, Bacon’s mouths, Helene Weigel’s mouth wide open screaming an empty loss in Mother Courage, Munch’s Scream. I guess that’s some of what I was writing towards in O Fallen Angel, what I’m really always trying to write towards, those who are dumb and deaf but inside writhing with unwordable agony, and are diagnosed as selectively mute, those who lack language so they commit violent acts, they are only given language that is banal and well-behaved , the need to burn burn burn but they cannot so they set fire to themselves, they self-immolate (as one of my characters does literally and the other does symbolically). The spectacle of this, of the wound, to borrow an idea from Mark Seltzer’s cultural study of the serial killer. And we gather around this wound, this trauma in our talk-show society, but then we also suppress it, the anguish, sadness, we medicate it. I also really love how much a reader Bacon was and we both share a passion for the Greeks, the Greek tragedy really inspired O Fallen Angel, especially The Oresteia, the choruses threaded, some of the imagery, and Malachi is a Cassandra figure, ranting, raging, never believed.