Nicholson Baker’s The Traveling Sprinkler

The Traveling Sprinkler

The Traveling Sprinkler

by Nicholson Baker

Blue Rider Press, Sept 2013

304 pages / $24.85 Buy from Amazon

Before we begin the review proper, an interesting parallel.

Nicholson Baker, in his 2011 Paris Review interview, on the writing of The Mezzanine: “It was totally absorbing, the feeling of being sunk in the midst of a big, warm, almost unmanageable pond. I could sense all these notes I had, all these observations I’d saved up to use, finally arranging themselves in relation to one other.”

Paul Chowder, Baker’s protagonist in The Traveling Sprinkler, quoting Claude Debussy answering a question about his compositional process: “Gradually after these thoughts have simmered for a certain length of time music begins to centre around them, and I feel that I must give expression to the harmonies which haunt me.”

Chowder, again, quoting Freud, “There are no coincidences.”

We first met the middle-aged poet Paul Chowder in 2010’s The Anthologist, as he attempted to write an introduction to a poetry anthology while navigating myriad distractions, from his lost lady love to the wealth of poetic knowledge residing within his own head. He was Baker by proxy, the writer of dirty books laid bare as an astute intellectual who has money and love problems, copious idiosyncrasies, and who just happens to have a masterful knack for nicknaming male genitalia (“Shropshire lad” being a particularly outstanding one this time around).

For The Anthologist, Baker recorded himself in various locations talking into a camera, attempting to be honest and naked in a way that writers often refuse to be behind the carefully composed written word. Honesty in writing, after all, is always edited, and has the benefit of a first draft.

Similarly, The Traveling Sprinkler, made heavy use of audio recordings, self-interviews, that were later transcribed and tinkered with and embellished into the continued adventures of Paul Chowder, who now finds himself owing a new book of poetry to his faithful publisher, who has now quit drinking Yukon Jack in the meantime, who wants to learn the guitar, who can only seem to write when parked in the shade in his Kia, who has once again lost Roz.

While The Anthologist was very much a book about poetry (well, among other things), this book chronicles our narrator’s love affair with music, from his early years as a promising bassoonist (a career path that was derailed by a basketball accident), to his new obsession with both singer-songwriters and modern dance music. Underworld is namedropped, Debussy’s “The Sunken Cathedral” is dissected in an out, and YouTube URLs to college students singing protest songs awkwardly conclude paragraphs left wanting for proper final punctuation. The only thing missing is an official Traveling Sprinkler Spotify playlist. Excuse me while I make one.

Are there any critics of serious literature remaining that vehemently oppose the appearance of modernisms in novels? If so, poor things, keep them away from The Traveling Sprinkler.

The line between Baker and Chowder is once again thin, if not opaque, but, like the book’s namesake Sears product, winds along in anything but a straight line. It can, admittedly, be distracting, as someone who obsesses over the biographical details of authors, to have to pause and wonder if what you’re reading is really how Nicholson Baker really feels about dance music or drones or climate change or even peanut butter crackers. When we read an obviously fictitious novel, we’re free to get swept away, but with Baker so close under the surface, we want him to be the one talking to us. This may, admittedly, be a hang-up limited to serious enthusiasts, and that particular longing shouldn’t be mistaken for critique.

What Baker has accomplished here is to give us, along with late-period David Markson, the best look into the writer’s brain, one that no Paris Review interview could even begin to reveal. More specifically, the aging writer, the one who no longer voraciously reads, and whose head is full of facts and knowledge, but who faces the very real possibility that the well might be dry and all that is left to do is a sort of self-inventory for posterity. The secret is, of course, that writers of all ages are doing just that, perhaps dressed up in a grand narrative or imaginative forms, but that nonetheless. Just ask the 31-year-old that wrote The Mezzanine.

The parallel with Markson is an interesting one, as Paul Chowder admits to never having been able to read novels, while Markson admitted (both in interviews and later by way of his own thinly guised fictional protagonist) to having run out of drive to read them, and that with five of his own still to come. Both writers eventually stumbled upon a groove in which they became literal anthologists of the contents of their minds, Markson right up until he died.

In an all-to-brief and somewhat stilted interview on The Colbert Report, Baker likened the traveling sprinkler to us, navigating the garden of our minds. I’m not sure there exists a more perfect, if idiosyncratic, metaphor for writing, although what force it is that pulls us along is still up for debate. Regardless of your answer, it’s worth celebrating that Nicholson Baker still has plenty of hose left.

***

James J. Fitze is a writer and editor living in New York City. A music journalist “in a past life,” James currently contributes to a living novel at thedownmachine.com.

November 22nd, 2013 / 11:00 am

THIS SEPTEMBER ISSUE: TWELVE REASONS TO CHOOSE HARPER’S

THE BRIEF HISTORY OF HARPER’S CLUB

Six days ago I received an email with the subject: “HARPER’S MAGAZINE RENEWAL.” The line of argumentation the email included was constructed by the magazine’s “Circulation Director.” I never read it, because I believe everything it said: I didn’t need to be persuaded in regards to the absolute necessity of my continued subscription. [1]

The motive that initially made me subscribe to Harper’s was my desire to intellectually engage on a more personal level with a friend from college, Dan. We both agreed that the depth of our homosocial rapports was not adequately profound, and because we enjoyed discussing with one another we eventually came up with the idea of what we jocularly referred to as “Harper’s Club.” [2] Dan’s academic interests were very different than mine, but we both enjoyed challenging various points of view in our pursuit of forming an informed opinion.

The planning of The Club’s meetings became impossible and our friendship never deepened. Regardless of this failure I could not be happier for the epiphenomenal ramifications of our failed initiative. By encouraging me to think about familiar subjects in different ways, “Harper’s Club” regularly challenged me as a thinker. This held true even when I was the solitary member of the Club, and continues to be valid to this day. Every time a new issue arrives in my mailbox I expect to encounter articles that serve this mission. My expectations are pleasantly surpassed consistently.

THOUGHTS ON ADS (ATTN: MIGHT BE FEELINGS!)

Nicholson Baker’s House of Holes Style Sheet

Deadspin has published the style sheet from Nicholson Baker’s latest, House of Holes, a self-proclaimed “Book of Raunch.”

Here are the As & Bs:

a-holes (38)

assbones (44)

assbuns (199)

asscheek (33)

assclenching (200)

asscrack (239)

assfucking (175)

ass jeans (240; see query)

assjunk (180)

ass pants (241; see query)

assplay (224)

ass-slappy (220)

ass-squeezer (27)

asstrunk (180)

asswood (57) READ MORE >

Cool piece on writing processes of a range of writers, including Kazuo Ishiguro, Michael Ondaatje, Richard Powers, Margaret Atwood, at Wall Street Journal [via Rozalia Jovanovic]

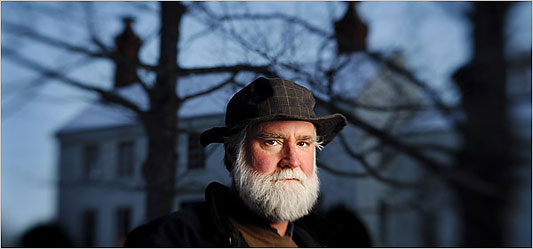

Most days, Nicholson Baker rises at 4 a.m. to write at his home in South Berwick, Maine. Leaving the lights off, he sets his laptop screen to black and the text to gray, so that the darkness is uninterrupted. After a couple of hours of writing in what he calls a dreamlike state, he goes back to bed, then rises at 8:30 to edit his work.

I Like Nicholson Baker A Lot

Last week I read Nicholson Baker’s new novel, The Anthologist, all in an evening sitting propped uncomfortably across the smaller of two sofas in my apartment. One thing about reading Nicholson Baker is in his exorbitantly minute and often startling descriptions (his first novel, The Mezzanine, is simply the thoughts of a guy during a ride up an escalator, which sounds boring but is incredible), you might think that it would then be easy to get caught up in the vibe, overthinking ideas and elements as you sit in the presence of a master doing the same. And yet, Baker is so good at catching all the spillage of thought you might have in listening to him speak, there is actually very little loosening of one’s own awareness while in the grip of even such an often everyday-aimed and frank voice as he wields. I hardly even recognized how uncomfortable I get usually while reading. It all went down, as have all of his books, leaving me hungry and excited, even in, again, a seemingly arbitrary subject matter: The Anthologist is about a guy, Paul Chowder, preparing to write the introduction to a poetry anthology. There is simply probably no one else alive who could pull this off, and Baker does, quite so.

15 ‘Towering Literary Artists’ Who Are Still Alive

By request, a list of 15 living writers who I would consider ‘towering literary artists,’ even though that phrase itself comes with the baggage of being a little silly, but still. These men and women all spit fire line by line, and have been doing so for many years, and continue to do so, as we speak.

This list, of course, is somewhat arbitrary in its compiling, as I just jotted down the first 15 towers that occurred to me, and there are many others that could have, should have appeared on this list, a list that likely could go to at least 30, maybe 50, and especially had I included authors with smaller yet still growing bodies of work. Here I stuck to people who mostly have published at least 8 books so far (I think here only one of them has less than that) (and if I opened beyond that this list would be easily twice as long right off the bat), and with a dearth of poets as I am not quite as done up in that area as in fiction, and therefore this list also clearly reflects my taste more than would a neutral and objective list of towering authors (i.e. a lot of people would easily switch out Lish for, say, John Ashbery, etc., or perhaps Diane Williams for J.M. Coetzee or Cynthia Ozick or John Barth): this therefore is more those who I feel towering among my own mind, in my history, but who also clearly have made their mark across the world at large. Feel free to comment and let me know all of those I left out, or make your own list, etc.

David Markson

William Gass

Bludgeoned with romance

Nicholson Baker’s quirky latest novel, The Anthologist, is comprised of failed poet Paul Chowder’s ruminations on poetry and how unrequited love for it has essentially ruined his life. Through it all, though—the rejections from Paul Muldoon, Chowder’s lady friend leaving him, the failure of his floundering flying spoon poems—he clings to the words and lives of Roethke, Bogan, Swinburn, Keats and the rest with a tenacity not seen since Bob Backlund’s crossface chickenwing rampage. It has actually inspired me to start reading poetry again, which I haven’t done regularly in some time (any recommendations?). All his talk of olde timey poets has also pushed me to check out Richard Holmes’s The Age of Wonder, a lovely book exploring the connection between gentlemen scientists of the day and iconic poets such as Wordsworth and Coleridge. Dudes were making enduring discoveries and creating timeless art long before they could even grow a proper pre-Victorian mustache! All very impressive. I suspect the era’s precociousness had something to do with all the frock coats, shoe buckles, pantaloons and widespread leeching. God save the Queen.

Nicholson Baker’s quirky latest novel, The Anthologist, is comprised of failed poet Paul Chowder’s ruminations on poetry and how unrequited love for it has essentially ruined his life. Through it all, though—the rejections from Paul Muldoon, Chowder’s lady friend leaving him, the failure of his floundering flying spoon poems—he clings to the words and lives of Roethke, Bogan, Swinburn, Keats and the rest with a tenacity not seen since Bob Backlund’s crossface chickenwing rampage. It has actually inspired me to start reading poetry again, which I haven’t done regularly in some time (any recommendations?). All his talk of olde timey poets has also pushed me to check out Richard Holmes’s The Age of Wonder, a lovely book exploring the connection between gentlemen scientists of the day and iconic poets such as Wordsworth and Coleridge. Dudes were making enduring discoveries and creating timeless art long before they could even grow a proper pre-Victorian mustache! All very impressive. I suspect the era’s precociousness had something to do with all the frock coats, shoe buckles, pantaloons and widespread leeching. God save the Queen.

August 27th, 2009 / 12:28 pm