A Tiny Addendum to Paul Auster’s Concept Concerning “Boy Writers”

On 16 January 2014, a writer boy named Paul Auster conversed with someone named Dr. Isaac Gewirtz (this boy likely had friends & relations who were a part of the Holocaust) at the Morgan Library (which seems quite splendid, though it may not be if Mayor Bloomberg was able to blow his matzoh-ball-soup breath on it).

According to girl writer & Huffington Post blogger Anne Margaret Daniel, Paul put forth the category of a “boy writer,” which means:

someone who is so excited, takes such a sense of glee and delight in being clever, in puzzles, in games, in… and you can feel these boys cackling in their rooms when they write a good sentence, just enjoying the whole adventure of it. And the boy writers are the ones you read, and you understand why you love literature so much.

I concur with Paul — because of “boy writers,” literature is the best thing ever (except Christianity).

Arthur Rimbaud is a boy writer, which is why he stabbed people at poetry readings and yelled “shit” after the insipid readers declaimed their dull verse.

Edgar Allan Poe, as Paul points out, is a boy writer, as he composed stories on murder and poems on special girls, like the “beautiful Annabel Lee.”

There’s not a lot of boy writers who are un-dead. Most, nowadays, correspond to what Paul terms a “grown-up writer.” Stephen Burt, Carl Phillips, Dobby Gibson, Geoffrey G. O’Brien, Bob Hicok are examples of a “grown-up writer.” They don’t spotlight the “puzzles” and the “games” of the violence, theatricality, exploitation, and upsetness in the postlapsarian world. They document liberal middle class averageness. “It’s about settling down and settling in,” says Burt.

But some boy writers are un-dead.

Johannes Goransson likes makeup and violence. “mascara is infected / belongs to assaults,” the Action Books editor and boy writer elucidates in Pilot (Johann the Carousel Horse).

HTML Giant’s own Blake Butler is a boy writer. In Sky Saw, his characters aren’t given names but numbers (just like in the Holocaust and in the War on Terror). Reading his books are sort of close to witnessing a disembowelment.

Paul Legault (because he likes Emily Dickinson like someone would like an American Girl doll), Walter Mackey (because he likes Barbie), and Julian Brolaski (because his language reads like sticky, sweet, chewy watermelon bubblegum), are all un-dead boy writers.

But the best boy writers (maybe ever) are dead, and they’re Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. Glee? Delight? Cackling in their rooms? Enjoying the whole adventure? All the attribute’s of Paul’s boy writer align with Eric and Dylan. They kept journals, websites, and videos so everyone in the whole wide world could be cognizant of the glee-enjoying-cackling-delight-adventure that they had in planning their massacre. As Eric stated, “I could convince them that I’m going to climb Mount Everest, or that I have a twin brother growing out of my back. I can make you believe anything.”

25 Points: The Emily Dickinson Reader

The Emily Dickinson Reader: An English-to-English Translation of Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems

The Emily Dickinson Reader: An English-to-English Translation of Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems

by Paul Legault

McSweeney’s, 2012

247 pages / $17.00 buy from McSweeney’s

[Note: In the text that follows, the leading number refers to the catalog number assigned to each Dickinson poem and its accompanying translation. These numbers are derived from the Franklin (1999) edition of Dickinson’s oeuvre. The trailing trailing number appearing in square brackets references the actual “point number”, and thus the in order in which the reviewer would prefer, although would not require, that these 25 points be read. JM]

12. Concurrent with my reading of Legualt, I’ve been following Brandon Brown @ Harriet (the blog) on translation. How he says, “There is no master.” I feels it applies here, too. But maybe Brown and Legault are colleagues, correspondents, even. (One of them, surely, is wren-like and sherry-eyed.) Or the inventions are independent identicals, like Darwin and that other guy*. I imagine Brown and Legault meeting in some profile coastal city with a very specifically desirably demographic profile, dotted with saloons and taverns, meeting over craft beers intensely hoppy and a shared literary ambivalence which tastes of salt without being salty per se. But this meeting, which is like a prelude to a deeper or longer encounter, this meeting wordless, sudsy… these beers, these refreshments bitter and compulsory… the possibility of Brown and Legault merely overlapping at the bar is as far as my imagination goes. And is this stopping heartful, braked by the anxiety of influence? “Emily Dickinson wrote in a language all her own, thus the need for this English version of what she meant.” (7) Wait, so does the agony of influence deny the mortification of the flesh? [3]

29. Handed over to the hand that writes, “simple” and “direct” are always driven forward. I mean, forward as out or away, into that exile that enable observation, not into the completed future of conveyance. (That, and I just don’t trust McSweeney’s.) [4]

98. Biography bugs me most of all. I wish we had no daguerrotypes of Dickinson to caption. I wish reading really pressed some sort of pause button on life itself. I wish I didn’t feel like I, too, know how caretaking will warp you. [16]

167. But with such rueful wishing, if not in it, a realization disappoints me with surprise and surprises me with disappointment: I have this idea all the time. [25]

221. Translation isn’t telling, much less re-telling. But it snags in the same temporal flow as does narrative. [7]

319. What was Dickinson herself translating? Emerson? Swedenborg? Whiteness: “racial,” temperamental, existential (not a word she would have recognized, not for all the tenements in Amherst)? The Puritanism that idles with such delightful perversity in Frost’s “The Generations of Men”? The erotics of a universal chlorosis? Proverbs she found when she dreamed of communion in the hills so misty from her gnomic lookout? Hell, that’s it. Dickinson, even her doubts are too bold. For all Legault’s contemporary light shines, it can’t cast her shadows. [8]

333. Not that I think Dickinson’s—or any poet’s poetry, for that matter—is inviolable. Reading it will always rough it up anyway. But what about introversion? [2]

392. Consider Paul Legault’s project a sort-of ekphrasis on Dickinson’s unwritten autobiography. Consider that Dickinson’s medium isn’t poetry, that Legault’s isn’t comedy (though more than a few of these read as if they could have been spouted by a vintage, arrow-through-the-head Steve Martin), that there is no translation evident here, only notation, only commentary, only adumbration, thoughts broken in the process of their own manufacture by the machine that is, quite literally is, addiction to the author’s held-out promise of exegesis. Consider your prurient self covertly mocked. [21]

421. Emily Dickinson isn’t your friend, and never was. Anyway, friendship thrives on novels (its parasitic), not poems. And Emily Dickinson does care, in the sense that she wants to know something true of her own being. That she would exemplar herself, if only privately. [20]

438. The apostrophe of the second-guess. The syntax of the spit-take. After all, the literal is the absurd. [13] READ MORE >

January 3rd, 2013 / 12:09 pm

The Other Poems interview with Paul Legault

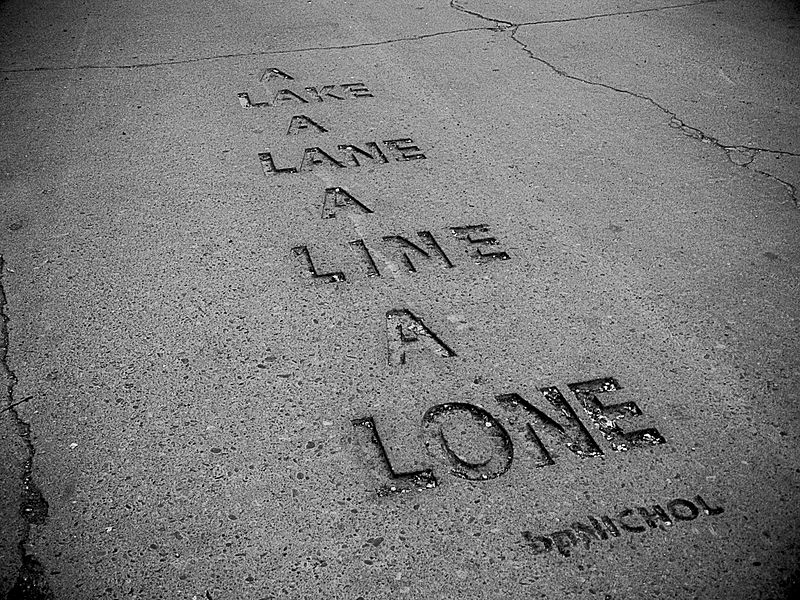

Sam Ross: Paul, your book begins with an epigraph from bpNichol:

From there the book erupts into a series of sonnet-dialogues with a host of personages, personifications, and “others”–from Whales, to Celibacy, to Mayakovsky as a Pony. Are these dialogues a means of approaching a dialogue with the self (as bpNichol suggests), mocking attempts at such a dialogue, or are the Others meant to be fragments of a unified self or whole (I’m thinking of a title of one of the Other Poems which begins: “We are made up of smaller version of ourselves stacked up on top of the smaller versions of ourselves….”). Maybe all three? Also, look at this!

(I like this.) READ MORE >