Affix Your Tinfoil Headware and Dive into The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick

The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick

The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick

by Philip K. Dick

Edited by Pamela Jackson & Jonathan Lethem

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011

976 pages / Buy from Amazon

Some authors’ lives are more interesting than their literary output. I’d rather read Ted Morgan’s excellent William S. Burroughs biography Literary Outlaw than any Burroughs’ book other than Junkie. Philip K. Dick led such a grandiose life that he’d belong in this category if he hadn’t written A) so many interesting novels and short stories and B) at least three major novels in Ubik, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch and The Man in the High Castle. He also left behind an unwieldy hunk of mystagogic scout work now known as The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick.

Let’s get some basic facts out of the way. Dick is popularly known as the author who inspired films like Blade Runner, Total Recall and Minority Report. He was mired in the pulp mills of sci-fi for most of his career (44 published novels; 121 short stories). He was prescribed (!) meth-amphetamine and gobbled whatever drugs he could pillage from his mother’s medicine chest. He enjoyed the company of five different wives. Most significantly, he experienced a series of mystical encounters:

1) A beam of pink light told him that his son had a rare, serious birth defect that needed medical attention. This couldn’t have been observed with the naked eye. At the hospital doctors confirmed Dick’s otherworldly diagnosis. His wife from that period corroborates the story.

2) When a delivery girl came to his door wearing a fish sign necklace that was worn by the early Christians, Dick came to believe in an underground network of secret Christians that he was being initiated into.

3) During a period of heavy amphetamine use, he looked into the sky and saw a menacing, metallic, malevolent god. This wasn’t a transitory hallucination. The old triple-M sky-god looked down on Dick for a number of days, serving as inspiration for his masterpiece The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch.

4) Most spectacularly, Dick reached the conclusions that:

– Time was an illusion

– Reality was a hologram

– The year was actually 50 A.D.

– The Roman Empire never ended

– Without having read The Book of Acts, he independently recreated parts of it in his novel Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said.

Much of this is revealed as the tractate in his novel VALIS, whichfrequently references Dick’s exegesis, defined as a “critical explanation or interpretation of a text or portion of a text, especially the Bible.” Up until recently, only a truncated version had been published, but self-styled Dickheads were desperate for more. Jonathan Lethem, Pamela Jackson and a team of editors dug through Dick’s cartons of manic exegeting and in 2011 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt published a thousand page volume titled The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick.

August 11th, 2014 / 10:00 am

25 Points: The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

by Philip K. Dick

Mariner Books, 1982

256 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

1. If Phil Dick were a preacher, I think there would be a lot more interest in religion with his unique blend of fantasy, science fiction, philosophical speculation, ontological conundrums, and church history.

2. I bought the Transmigration of Timothy Archer at a bookstore called the Last Bookstore which gave me an ominous reminder of the apocalypse, or perhaps just the end of paperback books. When I studied the history of Christianity at Berkeley, I was surprised to find out that in the year 999, people were convinced the end of the world would come on 1000 and mass hysteria spread across the world. 1000 came and went and the world is still here.

3. The character of Bishop Timothy Archer is based on a real life American Episcopal bishop named James Pike who was friends with Philip K. Dick. Bishop Pike lived from 1913-1969 and led a huge congregation at the Grace Cathedral. He was a controversial figure who supported the ordination of women, racial desegregation, and the acceptance of LGBT people. He worked in support of civil rights and marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. during his march to Selma, Alabama. He was an alcoholic, had a romantic relationship with his secretary, and was brought up on heresy charges multiple times for questioning the virgin birth and the existence of Hell. He was never convicted.

4. The Transmigration of Timothy Archer is the third book in a trilogy that includes VALIS and the Divine Invasion. You don’t need to read the first two to understand this one, though it helps. This one also has no science fiction elements in contrast to the previous two.

5. The book starts with the death of John Lennon and is told through the perspective of Angel Archer who is the daughter-in-law of Timothy Archer. Timothy Archer is already dead and she is reflecting back on his life and the fact that he sought “what lies behind Jesus: the real truth. Had he been content with the phony, he would still be alive.” He begins to question the identity of Jesus after learning about the discovery of the Zadokite Scriptures, now known as the Damascus Scriptures. In those scriptures predating Christ by two centuries, there are references to sayings Jesus made, suggesting the message was not entirely original. It’s those implications that drive Archer on his quest.

6. To be more specific: “My point is that if the Logia predate Jesus by two hundred years, then the Gospels are suspect, and if the Gospels are suspect, we have no evidence that Jesus was God, very God, God Incarnate, and therefore the basis of our religion is gone. Jesus simply becomes a teacher representing a particular Jewish sect that ate and drank some kind of— well, whatever it was, the anokhi, and it made them immortal.”

7. Anokhi means Pure Self-Awareness and was eaten at the Messianic banquet. The Last Supper Jesus had with His disciples wasn’t just a sharing of bread and wine, but in a parallel with Zoroastrianism and Brahman, an assimilation and unification with God.

8. Timothy Archer refers to John Allegro, the official translator of the Qumran Scrolls, who posited a theory in his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. That theory was that Jesus and His early disciples smoked mushrooms that gave them hallucinations and became the basis of their religion.

9. Jeff Archer, Bishop Archer’s son and Angel’s husband, has his own theories. He is particularly obsessed with the idea that “the ills of modern Europe” can be traced “back to the Thirty Years War which had devastated Germany, caused the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire, and culminated in the rise of Nazism and Hitler’s Third Reich.” A prominent figure in those times was the German general, Wallenstein, who “colluded with fate to bring on his own demise. This would be for the German Romantics the greatest sin of all, to collude with fate, fate regarded as doom.” Jeff Archer ends up committing suicide after he falls in love with the woman Timothy Archer is sleeping with.

10. Timothy Archer is sleeping with his secretary, Kirsten. READ MORE >

May 30th, 2013 / 12:18 pm

TWO OR THREE WAYS TO RESURRECT PHILIP K. DICK

Philip K. Dick: Remembering Firebright

Philip K. Dick: Remembering Firebright

by Tessa B. Dick

CreateSpace, March, 2009 & 2010

228 pages / $15.77 Buy from Amazon

&

Daughter

by Janice Lee

Jaded Ibis Press, 2011

144 pages / Color Ed. $39 Buy from Amazon or Jaded Ibis

B/W Ed. forthcoming Summer 2012

The last thing Philip K. Dick’s work needs is another philosopher’s commentary. After Fredric Jameson’s “synoptic” reading of Dick’s corpus and Laurence A. Rickels’ 400-plus page I Think I Am: Philip K. Dick, it might seem prudent, indeed respectful, to refrain from any further philosophical discussion of PKD. However, after spending some time with Tessa B. Dick’s “memoir” and Janice Lee’s “novel,” I am inclined to discuss a dimension of Dick’s that neither Jameson nor Rickels were able to deal with in their commentaries: namely, the particularly contemporary problem of living without myth. Anthropology tells us that peoples of the past actually believed in their myths; a mythological framework provided by the gods presumably told you how to lead your life and what your ultimate place in the universe was. Now that all of our myths have been more or less discredited by the advent of modernity, how might a viable contemporary myth cope with the disintegrating social edifice and the resulting modern subject who minimally experiences the “death of God”?

We’ll start with a strident way in – that of Daughter’s vision of “the head of a human figure with a terrifying face, full of wrath and threats” appearing to the protagonist “in the sky, on a night when the stars were shining and she stood in prayer and contemplation.” These two elements – the terrifying face of the big Other, and the lost subject in search of meaning and the miraculous – are constants in Philip K. Dick’s biography. In the late seventies, Dick recalled: “There I went, one day [in 1963], walking down the country road to my shack, looking forward to eight hours of writing, in total isolation from all other humans, and I looked up in the sky and saw a face. . . . and it was not a human face; it was a vast visage of perfect evil.” To the psychological impact of such an encounter, Janice Lee supplies a concrete example: “At the sight of it, she feared that her heart would burst into little pieces. Therefore, overcome with terror, she instantly turned her face away and fell to the ground. And that was the reason why her face was not terrible to others.”

April 30th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Something Film Understands but that Literature Doesn’t

I was talking with Jeremy M. Davies recently (actually, we were on our way to see Drive), and the topic of genre as art came up. Now, Jeremy and I are both huge into genre, in all media. We’re nuts over spy thrillers, sci-fi, and fantasy, for instance—not to mention Batman comics. (Only the good ones, though, natch.)

And of course lots of people in various lit scenes (all over) don’t think that genre fiction can be art. They’re really wedded to that “high art / low art” divide. (Or the “literary fiction / all else” divide, as it’s so commonly called.)

Me and J, we were saying how we don’t get it. How can someone read, for instance, Patricia Highsmith’s Ripliad and not recognize it as total artistic brilliance? Or Philip K. Dick’s VALIS, which is one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, hands down? And of course I’d argue that Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns is one of the finest things published in the 1980s, “despite its being” a comic book. (I didn’t spend all that time analyzing it at Big Other because I thought it was merely cute.)

Anyway, I came to a certain conclusion…

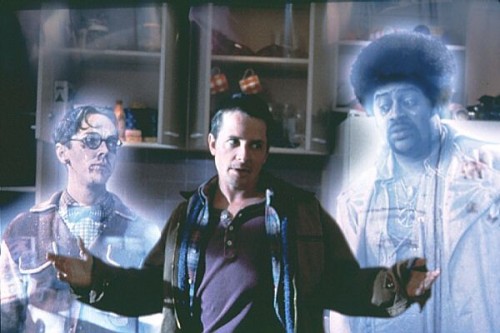

Craft Notes with Peter Jackson

I just finished watching the director’s commentary track on the re-issue of The Frighteners, a movie I truly love despite the fact that it’s deeply flawed, wildly uneven, and basically a failure. (It’s like the Philip K. Dick of horror-comedy crossover movies; though not like a Philip K. Dick movie). Hearing Peter Jackson discuss what he feels went right about the film, what went wrong, and how it all came together–or didn’t–was fascinating. I wasn’t much of a Peter Jackson fan going in–in fact I didn’t realize he had directed this movie until I netflixed it this most recent time–but something about his candidness, coupled with his obviously fan-boyish enthusiasm for cinema in general, really won me over. Plus I learned that he made a FOUR AND A HALF HOUR documentary about the making of this film, which apparently I need to netflix separately. As of this writing, it’s already on the queue. Does anybody else have favorite failed work of art, be they literary, musical, or filmic? I’d be interested to hear what, and why.

“How to Build a Universe that Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later” by Philip K. Dick

It was always my hope, in writing novels and stories which asked the question “What is reality?”, to someday get an answer. This was the hope of most of my readers, too. Years passed. I wrote over thirty novels and over a hundred stories, and still I could not figure out what was real. One day a girl college student in Canada asked me to define reality for her, for a paper she was writing for her philosophy class. She wanted a one-sentence answer. I thought about it and finally said, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”That’s all I could come up with. That was back in 1972. Since then I haven’t been able to define reality any more lucidly.

[After the jump, I write Ken a note about what I thought about the essay]