Rough Honey by Melissa Stein

Rough Honey

Rough Honey

by Melissa Stein

The American Poetry Review, Oct 2010

96 pages / $14 Buy from Amazon or IndieBound

Melissa Stein is the 2010 winner of the APR/Honickman First Book Prize for her book, Rough Honey. In the introduction, Mark Doty notes that Stein’s “sentences are beautifully choreographed; they start and stop the motion of her poems with a nearly invisible, effortless authority. Best of all, her concurrent attention to sound and to image makes the world, on these pages, viscerally real; she employs one of poetry’s oldest powers, yoking the referentiality of words to their sheer sonic force ” ( xi).

I don’t remember where I was when I first read one of Stein’s poems, but I do remember that I immediately ordered the book. I was struck by the combination of visceral and sensual language of her work. In “Whitewater” she begins with the flip of a kayak and an adrenaline rush:

like academics, frothfoamgrit and the taste,

what was it, asphyxiation, psychedelic Escher

in blackwhite cubes (6)

There is something sensual, almost first sexual experience whimsical in linking froth, foam and grit into one word to illustrate the initial plunge. There is a hint of the graphic results in her word choice “asphyxiation” (6). The shift upon the speakers face plant into a rock is an unusual blend of both sensual and visceral:

White protrusion of bone – white petals and light,

Pearl-solid, luminous, all fourth-of-July and scattered,

Pipe bombs bottle rockets Christmas crackers, oh,

What a party, annihilation (6)

The leap from “white protrusion of bone” to “petals and light, / Pearl-solid, luminous” (6) and pairing “Pipe bombs bottle rockets Christmas crackers” (6) is an example of what Hoagland (2006) calls the “pause that would never occur in “natural”, uniformed speech” (62), a self-conscious move that deepens the experience of the poem. It brings a range of emotion to this singular event, from war to holiday, in very few words.

Her voice is similar in style to how Hoagland describes Louise Gluck’s in his essay, “The Three Tenors”. Here, Stein’s “radiance and gravity [like Gluck’s] grow out of the enormous pressure exerted on the contents of a small container” (Hoagland 52). It’s no surprise since Stein considers Gluck to be one of her early influences.

Her tone is dialectical, passionate, detached. Stein shifts the tone of her poems by using the interplay between the sensual and the visceral to detach and create space. Again, in “Whitewater” after the initial thrill followed by impact, the speaker reflects on the surroundings in a sensual way as if none of this has happened:

the tenderness

of paint sable-brushed against silk, powdered

throat of the foxglove, flushed curve spiraling/into a conch

velvet crowing the doe’s nose,

arms embracing the cello’s hips” (6)

Here, she clearly illustrates what Doty has called the “start and stop motion of her poems” (vi). There is the flip/rush, the smashing of face into rock followed by that place where this is no pain.

November 18th, 2013 / 11:00 am

HOPE TREE

HOPE TREE

HOPE TREE

by Frank Montesonti

Black Lawrence Press, August 2013

90 pages / $9.95 Buy from Black Lawrence Press or Amazon

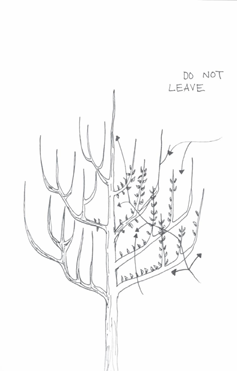

In HOPE TREE, Frank Montesonti literally prunes How to Prune Fruit Trees by R. Sanford Martin. Accompanied by simple drawings, lovely interpretations from the original sketches, the book is one of erasure.

Literary erasure is not without its critics. Jeannie Vanasco, in “Absent Things As If They Are Present” noted that “in 1820, in the preface to Prometheus Unbound, Shelley called complete poetic originality a ruse: “As to imitation, poetry is a mimetic art. It creates, but it creates by combination and representation.” HOPE TREE does just that. HOPE TREE is a risk, one that the author acknowledges in The Foreward: “I have hesi-/tated / I was aware// I have tried to make/ my instructions simple”

Illustrator: Miranda Polley

HOPE TREE is an espalier of words, both visually and metaphorically. The title, a play on the original, is interesting. HOPE is derived from a portion of the original title, How tO PrunE. Montesonti has tipped his hand. Pruning is initially a brutal activity, but also a hopeful one. When done correctly, the tree thrives, produces more fruit and becomes even more strong and beautiful. If not, the results can be an ugly mess, possibly fatal. It is all about the balance between aesthetics and necessity, a combination of knowledge with a leap of faith.

The same can be said for writing poetry. It is never easy to part with a word or favorite line even when it is abundantly clear that it must be done. As difficult as it is to do with your own words, erasing someone else’s words, while it might seem easy, is a much more complex and difficult task. This is not an exercise in editing. It is an exercise in pruning in the original sense of the word, to cut where the most growth will occur. Montesonti aptly notes “the coarse frameworks / may be very beautiful //as they// choke off the circulation” (32).

October 4th, 2013 / 11:00 am