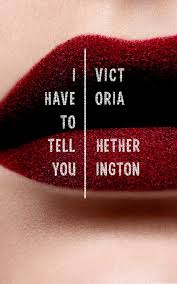

I HAVE TO TELL YOU by Victoria Hetherington

I HAVE TO TELL YOU

I HAVE TO TELL YOU

by Victoria Hetherington

0s&1s, June 2014

151 pages / $6 Electronic. Buy from 0s&1s

There’s a questionably selected excerpt from Victoria Hetherington’s I Have to Tell You available as a preview. It’s from the point of view of a college woman sitting around smoking weed with friends. Written with great veracity, this is as interesting as being the sober listener of a high college student retelling in detail her conversations (not very). Only when the excerpt culminates in the woman’s reflections—

—is the writing characteristic of Hetherington’s excellent first novel as whole: graceful and poignant, often redolent of Annie Dillard’s sparing prose rising to beautiful abstractions, open to the everyday’s influence on personal narratives.

I Have to Tell You is a catalog of pain splintered into multiple characters’ points of view in chronological episodes. Their story is told predominantly through first-person narration, but also through shorthand journal entries, emails, and google searches. It is a litany of voices trying to understand and rationalize their pain to themselves. Some may be put off by this agonizing, but it is not facile, solipsistic, or ironic agonizing—it is instead Socratic, a desperate dialogue with hurt, loss, impending death, and the social devaluation of aging. But all this pain talk is not to say Hetherington isn’t funny or clever, which she often is; writing about pain in fiction often benefits from humor, especially when it’s the pain of white middle-class Torontonians.

Hetherington’s characters indulge in their suffering, which becomes an act of resistance to what creates suffering. Cocaine abuse, erotic desire incommensurable with politics or friendship, an aging woman who gets plastic surgery because she sees in her own reflection the face an acquaintance makes at the moment of death; these self-destructions are resistances, announcements of the pain that goes hand-in-hand with living fully in the world. Their experience of misery is reminiscent of an old saying of Chinese criminals about to be put to death: “In twenty years I will be another stout young fellow”. It’s a proud act that challenges suffering by embracing it scornfully, acknowledging its cyclical pervasiveness.

Suffering in I Have to Tell You also recalls the Western biblical mythos surrounding gender and reproductive organs. Menstruation as God’s punishment is the biblical explanation of a biological phenomenon present before the Bible. Circumcision is a covenant God makes with men in order to arrange for divine dominance of their reproduction. One is an explanation. The other is a prescription. Here, women are punished simply by existing and must find meaning in light of this. Men are made to suffer (or subscribe to suffering) in the name of meaning, for some supposed higher and vaunted power. Similarly, men in I Have to Tell You see their suffering as a cosmic agreement in order to secure some noble identity. This is the case for a character who ascetically and sentimentally makes the woods his home as he prepares for death. Conversely, women are made to suffer merely by existing; they seek a way of explaining and living within the pain from which, being that of culture and stemming as far back as childhood trauma (as in one character’s teenage “relationship” with a strange abusive older man), they cannot escape but can perhaps revolt against. This is not to say the book has an uncomplicated rift between how different people experience pain; everyone, of course, experiences pain and everyone experiences it differently. But the distinctions Hetherington draws between the attitude and culture that surrounds male and female pain in I Have to Tell You, even the self-proclaimed feminist men (who, we see through one character’s specious arguments, still just don’t “get it”), rings true.

Despite their shortcomings, Hetherington respects her characters with an unassuming commitment to unironic truthfulness, showing great proficiency for writing in different voices that speak through a variety of media, woven together with beauty and coherence. The inclusions of technology lack clumsiness or forced cleverness; it’s an organic outgrowth of her characters’ natural assertions or understandings of identity. If there ever is a “Great American Novel” (a probably stupid concept) this is how it should look—but of course it’s Canadian.

***

Joe Hogle lives in Pittsburgh, PA. He is also known as poopsmithey, Ronny Cammareri, and ~LEATHA WHIP~. You can read a hypertext story and some of his poetry here.

June 27th, 2014 / 10:00 am