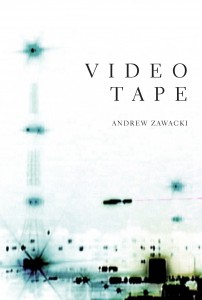

Sad & Hyperreal: Tracing Science Fiction Poetry Through Andrew Zawacki’s Videotape

Videotape

Videotape

by Andrew Zawacki

Counterpath Press, 2013

128 pages / $14.00 Buy from Counterpath or Amazon

“Science fiction poetry” is already a confusion of forms, a mash-up of brainy and hoity, nerdy and emotional, clunky and raw. If both science fictional and poetic, must this inter-genre be narrative-oriented, pithy, lyrical, and riddled with lasers? What else can we call it? “Science poetry” doesn’t account for future-speculation per se. “Cyberpoetry” resonates with cyberpunk and prescribes the rubric for an internet made 3D—strung up with tubes every shade of the neon rainbow. William Gibson himself, the supposéd godfather of cyberpunk, rejects the term applied to both his and his contemporaries work because it reduced what could’ve been a revolutionary alteration on the larger science fiction genre to a subgenre and therefore made it separate and disarmed. “Futurist” or “neo-futurist poetry” already has its predecessors in Marinetti, Mayakovski, and the like. “Speculative poetry” becomes overwhelmingly broad and “futurepoem” has already been claimed by a fabulous small press. For now, we’ll stick with science fiction poetry because everyone knows what we’re talking about when we say it, and any discussions based around the term should necessitate we at least acknowledge it as a genre that will be constantly at war with itself, a form containing two disparate worlds, that, most of the time, would probably rather not have anything to do with each other in the first place.

Many have gone to extreme lengths to define both poetry and science fiction separately and they are indelibly linked by a desire to write down what cannot possibly ever actually be written down. Ben Lerner talks about an Allen Grossman essay called The Long Schoolroom in his Believer interview, citing that Grossman calls all poetry “virtual” because it explores “an unbridgeable gap between what the poet wants the poem to do and what it can actually do.” For the world of poets, while our want may be for access to that Platonic ideal hovering above, we are also caught up in an inevitable failure to ever reach that world. So it is for science fiction writers, except they are concerned with the future rather than the divine. Where they may use the vocabulary of science and technology in order to provide insight into how the nuances of that future may one day appear, poets look to music, linguistics, and extreme concision in order to record their pursuit of those sublime, unknowable moments of everyday life. The rest is simple addition. Science fiction plus poetry equals a work that looks to material “progress,” the sonic, semiotics, and the pages white space in it’s pursuit of both spiritual transcendence and a prophecy for that grand tomorrow.

Another way to define a genre, as always, is simply to point the people who practice that genre well. Cathy Park Hong discusses science fiction poetics in one of her Harriet posts, where she outlines Andrew Joron’s Science Fiction, the most committed exploration of science fiction poetry to date. Hong dabbles a bit in the genre herself in Dance Dance Revolution and the “The World Cloud,” the third section of her own Engine Empire, with poems like “Engines Within the Throne” and “A Wreath of Hummingbirds.” There are countless others who’ve taken a crack at science fictionish projects in recent years. From genre-poets like Hong to conceptual writers like Christian Bök, to Pulitzer prize winners like Tracy K. Smith, everyone seems to be getting a piece. Bök isn’t interested in the conceits of science fiction as a genre, but is willing to spend nine years in a lab teaching the genome of a bacterium to store and write a poem that should last long after the human race is extinct. He calls it The Xenotext and however outlandish the project may seem, he has had a surprising amount of success. Other Conceptual poets, like Kenneth Goldsmith and Josef Kaplan, construct poems dependent on their own machines. Goldsmith’s projects succeed or fail based on how they are figuratively programmed to reproduce. The common language in his transcriptions of news anchors and weathermen are interesting because he captures human malfunctions in otherwise robotic speech, while the success of Kaplan’s Kill-list depends on the rage it provokes in the hivemind’s many forums and comment threads on the web.

“It’s all science fiction now,” is the oft-quoted phrase in these sorts of discussions, which Hong transmits from Joron and which Joron beams-up from Allen Ginsberg and Arthur C. Clarke. We’re turning to the futures of the past in order to interpret a society more and more affected by accelerated progress. Indeed, the list of poets goes on—Heather Christle has poems that unabashedly employ zeros and ones, cybernetic trees, holograms, and sublime computer programs in What is Amazing and elsewhere. Modern Life by Matthea Harvey contains a series of poems about a robotic boy and his half-human perceptions. Ben Mirov tracks the clicks of our increasingly cybernetic brains in Ghost Machine; Mathias Svalina obsesses over the beginnings and ends of all things in Destruction Myth; Timothy Donnelly offers the sky for purchase in Cloud Corporation; and Jasper Bernes enacts a dystopic LA in Starsdown. Even Pulitzer Prize-winner Tracy K. Smith toys with future-speculation in Life On Mars. Johannes Göransson and Joyelle McSweeney proclaim themselves Futurist in their Action Books manifesto, and McSweeney revels in a future plague ground, a poetics of doom, in much of her own writing and criticism. After all, Tao Lin is basically Neo, who opted out of The Real and instead chose to remain dangling in his giant pink egg sac, so long as he had access to a Macbook Pro.

January 17th, 2014 / 11:00 am