Web Hype

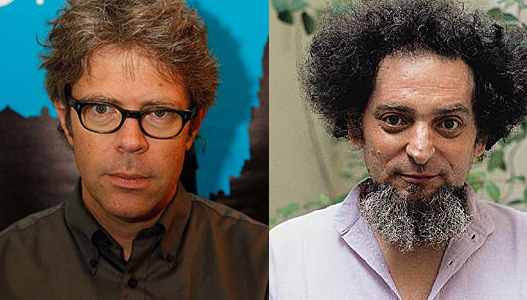

Franzen’s Status

This follows Roxane’s Tuesday post, and Jami Attenberg’s initial observation/criticism of something she heard Franzen say. Their defense of Twitter/Facebook/etc. is of course right: small press writers and publishers need those tools to promote themselves and their works. But I’m less convinced that Franzen has “lost perspective,” as Attenberg puts it, or “doesn’t understand what Twitter is for,” as Roxane claims. Instead, I think Franzen is making a deeper, more disturbing criticism—the latest salvo in a decade-long attack on certain writers, certain kinds of fiction, and ultimately, a certain construction of art itself.

To grasp all of that, let’s look more closely at a different part of his complaint:

[Twitter is] like writing a novel without the letter ‘P’…It’s the ultimate irresponsible medium.

Um—huh? What do lipograms have to do with social networking? And how are they irresponsible?

To understand what Franzen’s getting at here, we need to exhume his ten-year-old attack on William Gaddis, “Mr. Difficult” (which is relevant again, anyway, with Dalkey Archive Press having recently reprinted The Recognitions and J R). There, Franzen took Gaddis to task for being too much of a “Status” writer. What’s that, you ask? In Franzen’s purview, it’s a writer who operates under the assumption that

the best novels are great works of art, the people who manage to write them deserve extraordinary credit, and if the average reader rejects the work it’s because the average reader is a philistine; the value of any novel, even a mediocre one, exists independent of how many people are able to appreciate it. […] It invites a discourse of genius and art-historical importance.

Opposing that (Franzen continues) is the “Contract model,” in which

a novel represents a compact between the writer and the reader, with the writer providing words out of which the reader creates a pleasurable experience. Writing thus entails a balancing of self-expression and communication within a group, whether the group consists of “Finnegans Wake” enthusiasts or fans of Barbara Cartland. Every writer is first a member of a community of readers, and the deepest purpose of reading and writing fiction is to sustain a sense of connectedness, to resist existential loneliness; and so a novel deserves a reader’s attention only as long as the author sustains the reader’s trust. […] The discourse here is one of pleasure and connection.

There are numerous problems with Franzen’s two-model account, which has been dissected and criticized extensively elsewhere. (Here, e.g.) For starters, Franzen implies that writers and readers of difficult fiction aren’t pursuing pleasure, but cultural capital. (Franzen confesses that he himself once did that, and everyone must be like him, no?) He also subtly (subconsciously?) assigns “fathers” to the Status side, “mothers” to the Contract—yeesh.

Returning to that novel lacking a P. It’s easy to see why Franzen would file lipograms, and presumably all constraint-based writing, under the dreaded Status heading. When Georges Perec sat down to write La disparition, he didn’t do so because it would be easy! And his constraint—to write a novel without using the letter E—was a rule that couldn’t be broken, regardless of whatever that Perec might have wanted to do: make the writing funny or sad, thrilling or boring, plausible or implausible. It entailed its own artistic logic that trumped everything else. (The missing E was his dominant, that which could not be sacrificed lest the text lose its integrity.)

In Franzen’s eyes, this is pure Status fiction—the novel as a means of showing off. We can practically see his eyes narrowing in suspicion: it’s nothing but a stunt! From here we can rehash the reasons why some folks today don’t take, say, Tao Lin seriously: as Joshua Cohen characterized it (wrongly, I’d argue) “the writing is beside the point.” (Well, let’s set that one aside for another time.)

Of course, Franzen’s putdown disregards the fact that it’s difficult (ha ha) to imagine a more mischievous, more generous, more fun-loving novelist than Georges Perec. Sure, Gilbert Adair’s mid-90s translation of La d (A Void) is pretty rocky, but Perec wasn’t a showy, “look at me” kind of guy. (And so what if he was?) He genuinely loved puzzles, which are—fun! Although, admittedly, they’re sometimes hard to solve … (Incidentally, I’ve heard that the Oulipo have a secret constraint that governs all their works: “Be charming.” And what is that if not an explicit acknowledgement of the Reader?)

But I think Franzen understands all this—that some people love difficult, challenging things. I think that’s precisely what unnerves him. He reminds me of nothing so much as the fellow who’s so concerned that others are constantly pulling one over on him—telling jokes designed to go right over his head—that he resolves to abandon the conversation entirely: “I’m not going to play your mean, tricky games! I’m heading home, to read something comforting!”

Thus, it makes sense that Franzen would pooh-pooh social networking. He understands exactly what it is, and what people often use if for—and he severely disapproves. It’s obvious in his quote that he is Not Happy with this new technology—hence his calling Facebook “sort of dumb.” (That’s what you are, silly, if you enjoy it!) Hence, too, his extremely loaded acknowledgement that “it’s a free country,” which is obvious code for “while you may be free right now to be doing these things—you shouldn’t be doing them!”

I mean, c’mon—Franzen can’t be blind to the myriad ways in which social media has assuredly helped his publisher make him a Great American Novelist. And here you and I are, discussing the guy once again. Take that, independent lit! (Independent from what?) No, what I think dismays Franzen about social networking is its potential for constant performance, for constant broadcasting of status—which is, in the case of Twitter, a super-constraint-based performance! 140 characters or less—why, it’s the New Oulipo! (I would have called it “the noulipo,” if that name weren’t already taken.)

But Franzen is pretty clever, and knows well to mask his social anxieties as “looking out for others”:

People I care about are readers…particularly serious readers and writers, these are my people. And we do not like to yak about ourselves.

The man’s first rule of writing is: “The reader is a friend, not an adversary, not a spectator.” You’ve got to do nice, not play tricks on one another. Focus-test your novels, revising any sentences that folks don’t get right away. Cut some slack, use synonyms for the more impracticable harder words. Ask what readers want to read.

Does Snow White resemble the Snow White you remember? Yes ( ) No ( )

In the further development of the story, would you like more emotion ( ) or less emotion? ( )

Do you feel that the creation of new modes of hysteria is a viable undertaking for the artist of today? Yes ( ) No ( )

Would you like a war? Yes ( ) No ( )

Has the work, for you, a metaphysical dimension? Yes ( ) No ( )

What is it? (twenty-five words or less)

Do you stand up when you read? Lie down? ( ) Sit? ( )

In your opinion, should human beings have more shoulders? ( ) Two sets of shoulders? ( ) Three? ( )

Young authors take note: extensive demographic research presumably lurks behind Franzen’s rules. “Write in the third person unless a really distinctive first-person voice offers itself irresistibly”—that’s what most appeals to readers ages 18–34. (He and James Wood should form a club.)

For anyone who finds these criticisms unfair, rest assured that this is the telos of Franzen’s logic. Remember, it’s the Status writer who believes that “the value of any novel, even a mediocre one, exists independent of how many people are able to appreciate it.” Folks didn’t buy or like The Recognitions in 1955? That doesn’t mean it wasn’t great. But from the POV of the Contract, a book’s greatness can be measured by how many copies it sells, or fails to sell. The logic of the Contract is the logic of capitalism—not art. Sure, Franzen pokes fun at this view—

Taken to its free-market extreme, Contract stipulates that if a product is disagreeable to you the fault must be the product’s. If you crack a tooth on a hard word in a novel, you sue the author. If your professor puts Dreiser on your reading list, you write a harsh student evaluation. If the local symphony plays too much twentieth-century music, you cancel your subscription. You’re the consumer; you rule.

—but he also endorses it. Worrisome. (This endorsement frees Franzen up to confess that he’s never finished Moby-Dick, The Man Without Qualities, Mason & Dixon, Don Quixote, Remembrance of Things Past, Doctor Faustus, Naked Lunch, The Golden Bowl, and The Golden Notebook—despite the fact that those books are all really enjoyable.) (OK, I haven’t read The Golden Notebook—yet!)

This would be funnier if Franzen’s “free-market extreme” were, you know, more imaginary. But that bit about harsh student evaluations? I’ve seen that happen. And most large presses don’t feel any need to keep difficult classics in print. The damn things don’t sell—the hell with them! But don’t cry for those teachers or authors: they were being “irresponsible.” (Beware you disrespectful Twitter users! You’ll get yours, too!)

Here’s something I don’t fully understand, though—Franzen’s current use of “serious.” (“People I care about are readers…particularly serious readers and writers, these are my people.”) In “Mr. Difficult,” it was the Status crowd who commanded that term:

It wasn’t until the nineties, after I’d wasted a year on the screenplay, that I tried to rekindle my collegiate excitement about really hard books. I needed proof that I was a serious Artist […] and “The Recognitions” was perfect for the task. Reading the whole thing would also confer bragging rights. If somebody asked me if I’d read “The Sot-Weed Factor,” I could shoot back, No, but have you read “The Recognitions”? And blow smoke from the muzzle of my gun.

“Serious” there was a thinly-disguised synonym for “fake” (or “hip,” or “cool”)—so it makes sense that Franzen would want to reclaim if for his Contract peeps. Today, it apparently means genuine. Your status should be apparent from what you do, from what you read and what you make—which should be sincere expressions of yourself, not pretensions:

I have heard of your paintings too, well enough; God

has given you one face, and you make yourselves

another: you jig, you amble, and you lisp, and

nick-name God’s creatures, and make your wantonness

your ignorance. Go to, I’ll no more on’t; it hath

made me mad.

The more I poke at this, the more it reshapes itself into what might be the most central debate in the literary arts since at least 2000: “What, if anything, is now genuine?” (See, e.g., the New Sincerity.) Which makes perfect sense, given the way in which the Internet is increasingly colonizing our lives. What if the journal that just accepted my story is secretly a middle-aged, pedophilic, sentient robotic cat?

Beyond this, I have to say (I am honestly compelled to confess) that I was struck by how the conclusion of Roxane’s post echoed Franzen: “do what you like” (my emphasis), “keep it real.” Mind you, I’m not attacking Roxane (or the New Sincerity)—and I absolutely don’t want to accuse either of pursuing the same odious end as the market-driven “J F.” But I doubt that Roxane’s rhetoric, while admirable, will do much to rescue us from the Franzens of this world.

OK, time to wrap this up—before I started writing, I set an arbitrary 1969-word limit (the year Perec published La disparition). Here’s what I see Franzen as having “genuinely” said:

I say, we will have no more publishing:

those that are published already, all but one, shall

remain in print; the rest shall keep as they are. To a

bookstore, go.

[I’m assuming, of course, that Jami Attenberg’s transcription is accurate. So are you.]

Tags: Dalkey Archive Press, donald barthelme, facebook, Georges Perec, hamlet, jami attenberg, jonathan franzen, Joshua Cohen, Mr. Difficult, New Sincerity, oulipo, roxane gay, Tao Lin, The Dominant, twitter

I wonder if you would say if ‘authenticity’ was at the moment a general American occupation, not just a literary one?

I am thinking of an instance where I was speaking to an American who was going to a ‘genuine wake’ after a funeral. I told him that I had been to a wake, we have wakes where I’m from. He said ‘no, this is the authentic deal, they’re Irish’, negating my (non-Irish) experience, in favour of some sole truth he held of wakes everywhere. As if this was something to compete over.

I wonder why serious writers don’t like to yak about themselves. There is no one I would rather read about than a writer who will write whatever they think they are in such a wayyyyyy that the writing is well written. So that’s a shame. But maybe serious writers aren’t good writers after all.

[…] This is exactly half right about Franzen. What I mean is that it is exactly right in the direction it’s looking. Franzen is […]

i like his moral code. he is the rick santorum of writers.

Pertinent to the discussion of Franzen´s opinions on art is the major spanking he got from the publishing world after declaring, upon the publication of The Corrections, that he was “solidly in the high-art literary tradition,” and that Oprah´s club was “sort of a bogus thing”. After which comments Oprah decided to drop him from her Club, diagnosing him as “conflicted” (which seems oddly appropriate since he insists on preferring “serious readers and writers” while at the same time disliking “difficult fiction”).

He eventually made it to Oprah with Freedom. Which is truly part of the about-face he did: artistic integrity in exchange for popularity. This would not be so apparent was he not so vocal about what is art and what is not, what is a novelist and what is not, what is a novel and what is not.

He is, in the purest, most exact sense of the word, a sellout. Not an elitist that became a populist, but an aspiring artist who was in it for the ego-stroking and eventually -after the Oprah fiasco- realized what he was really looking for with his writing.

http://bostonreview.net/BR27.2/campbell.html

Great use of Hamlet. But where are you going with the “do what you like” thing? It seems that’s what social networking is all about–why else would people be doing it? Franzen objects in his fustian way because he’s pseudo-fascist in his literary values, the Lady Bracknell of the best seller list.

I for the life of me cannot find this essay I just read on thriller best seller and 7-figure-paid novelist Harlan Coben, but — shouldn’t Franzen be writing thrillers to bear out this ethos? They sell circles (and therefore reach way, way, way more people) than literary fiction. And shouldn’t he be contributing to Cosmo and Reader’s Digest rather than the New Yorker?

It may be at that. But I think it’s especially central right now, for many reasons. In the case you cite, one possible argument is that the success of identity politics has made it all the more important for people to find their “genuine” selves.

Which doesn’t always mean being genuine, mind you.

Look at my debate with Chris, where he says he doesn’t care to read anything a writer says about his or her own work. It’s a widespread prejudice (with different motivations—Chris’s logic, I’m sure, is different than Mr. F’s).

Yeah, absolutely.

I had a similar notion, once, but the contract required us both to come towards each other, and ‘being accessible’ wasn’t the only way for an author to move toward his audience, nor did ‘having bought the book’ stand in for our role in the readerly dynamic.

Sorry if that wasn’t clear. Franzen seems to be saying, “Be honest, and do things only if you enjoy them. Don’t do things because you think they’ll give you a leg up on other people.” (That’s why I italicized like—to try showing its loaded meaning—but I guess the font didn’t contain all that!)

The problem is twofold. One, some people like reading difficult books.

Two, how does capitulating to the reader equal writing honesty?

Franzen, it seems to me, consistently mistakes his tastes for everyone else’s. He sees someone reading Don Quixote, and thinks they must be showing off, forcing the words down to appear smarter than someone in Kansas.

I think he’s a pseudo-intellectual reactionary who enjoys telling educated people what they should be doing to appear less like intellectual liberals.

David Brooks, Thomas Friedman, James Wood, …

I wanted to look for the part where you explain how using the same bad logic you say Franzen uses is an effective counterargument, but the essay was just too damn tiresome to do so. So I’ll just continue the momentum you’ve established of assuming the worst motives on everyone’s part.

The new Dalkey edition of The Recognitions has several blurbs from Franzen directly taken from Mr. Difficult. They completely sidestep his criticism of Gaddis — the blurbs make it seem like he unequivocally loved the book. And yeah, he expresses admiration for it, but he also thinks it’s responsible for the decline of current fiction. And I’d have a problem with Dalkey’s misuse of the article if I didn’t think it was a pretty good fuck you to Franzen.

Also, I’m similarly confused and fascinated by Franzen’s use of the word “irresponsible.” Does he mean that the author has a responsibility to withhold the mundane details of his life? That the author’s words are so precious they cannot be used to describe a trip to the grocery store, tell dick jokes, talk shit about college basketball?

“A writer takes earnest measures to secure his solitude and then finds

endless ways to squander it. Looking out the window, reading random

entries in the dictionary.” (DD, PR #135)

you can add to that “occasional fucking around online,” which is fine, but if the Serious Author destroys that solitude via constant presence in the social mediasphere, that is Irresponsible to the work itself. it’d be like trying to write a good, Serious book at a raging orgy. which, if you like constraints: go.

it seems franzen submitted his opinion and we are falling all over ourselves to prove that opinion wrong. why?

are we really worried that an otherwise throwaway comment (that would have never seen the light of day and would have never gained as much traction as it did without it being trumpeted here) is a threat to Us?

Franzen is right without knowing why he is right. I like people who are right in spite of completely invalid assumptions, corrupt data, and outmoded viewpoints. Good artists don’t ever have to know why they are right. If they want to know why they’re right, they can go do a spreadsheet. As for Twitter, has anyone perchance followed William Gibson’s tweeting? Don’t.

After being on twitter for a couple months I’m prepared to declare that it is just plain boring. It’s boring. Or… merely interesting. Like a lot of the stuff Franzen is bitching about. I feel a sort of gut connection between the two. Just by observation, nothing that can be defined. Fleetingly, merely interesting, ultimately boring and narcissistic. Also, is possible for artist to be narcissistic and work not being so, vice versa.

I really just want to kick Franzen in the shin most days.

You are miscontruing Franzen’s remark by taking his “novel without the letter p” example too literally. He is saying that 140 characters are not enough to say something worthwhile. That is not a position I would care to defend, but I don’t understand why you are going out of your way to mischaracterize it. He is not objecting to Twitter because he thinks it is avant garde, which would be absurd, but simply because he sees it as too limiting.

“Mr. Difficult” begins with a reader putting Franzen in the position of ‘Mr. Difficult’, which reaction (to The Corrections) caused Franzen to realize that

In other words, Franzen’s self-awareness of his conflicting allegiances are plain to all but determined Franzenfreudeans: he understands his sensibility to be mixed.

He frames the crux so:

What Franzen makes clear about The Recognitions is that a) an attack on its difficulty would find confirmation in his experience of it, and b) he “loved” it.

Franzen’s inward conflict is not impossible to process: he loved something difficult. (–which “love” he calls “to [his] surprise”.)

His argument about Gaddis’s later books is not more obscure: for Franzen, a pleasurably difficult writer became by degree – book by book – an unpleasantly and fruitlessly difficult writer.

(It’s not in agreement with his assessments of Gaddis’s later books that one sees the reasonableness of Franzen’s growing resistance.)

The pleasure/work dichotomy, handled dogmatically is – as juan points out well with the apparent “serious”/”difficult” incompatibility – self-contradictory in Franzen’s own account of it. Difficulty sometimes delights in its artfulness, and easy engagement often bores and repels. That’s so uncontroversial a point of view that it’s itself almost anodyne.

Franzen’s self-account – which seems to me accurate – is that he’s ambitious to be “serious” but also to be a pleasure to work through, which is not the Great Villainy that Franzenfreudeans – however busily – carelessly fabricate as “Franzen”.

The reason it’s important to pick up on this throwaway comment about lipograms is that it demonstrates how F. casually casts formal play as a waste of time. F’s basically saying such a sentiment needed no defense.

I also think it’s right to pick up on the way F. likes to comfort his readers by telling them (repeatedly) how right they are to read formally and linguistically uninventive accounts of lives very much like their own, how that makes them serious but not pretentious. The above comment comparing him to Thomas Friedman and other purveyors of warmed over neo-liberal comfort writing was very apt.

Also also: The below comment about F.’s aesthetic being mixed is, I fear, too generous. It is not so much mixed as carefully pitched to appeal to an arrogance that wishes to see itself as unpretentious. It sees the middle-brow as a cultural peak to be defended against the the threats of both the high and low. And I don’t think that people hate Franzen out of simple jealousy but because he is the loudest spokesperson for a model of fiction that proposes we’ve reached a Fukuyama-esque ‘End of History’ for the form (that revolting self-congratulatory neo-liberalism, again, in another form).

Finally, a genuine question: Has JF ever said anything about poetry?

Agreement, Ben. Though I think it goes even further. What infuriates me so much about Franzen isn’t necessarily his dumping on difficult, formally-playful work. Because that’s ultimately a matter of taste, and his taste is just awful.

What’s dangerous about the man is that he openly endorses the view that the logic of the novel should be the logic of capitalism. In other words, he’s opposed to literature as art. That’s what pisses me off more than anything.

I think Dalkey was openly fucking with Franzen there. I worked for them right after “Mr. Difficult” came out, and the man was not popular around the office. Nor around Illinois State University in general; DFW was still there, and a lot of people felt burned.

Franzen is making arguments. And arguing about arguments is what people do, both online and off.

Arguments made by rich, powerful people have consequences.

No, you’re missing the point. Franzen is opposed to anything in writing that interferes with the Contract. Formalist constraints are one such thing. It’s a pretty old debate at this point.

yeah, i hear you. i guess i was gesturing to that but not saying it outright. but yeah, he’s this weird self-styled champion of culture who doesn’t believe in the possibility of literary art, which is a totally fucked position. plus he’s also kind of unreadably boring

I am aware of Franzen’s views on experimental writing. But the remark you quoted was not about experimental writing, and if you really think it is you’re just misreading it. Idk what else I can say.

The fact that this cranky dismissal is a throwaway remark is no evidence that Franzen thinks “such a sentiment need[s] no defense”! The throwaway remark is a literary form that need not drive any other – like the critical essay – out–that’s the accusation Franzen seems to be making of twitter, no?

“Formal play” isn’t what Franzen is attacking; he’s saying that what he thinks is ‘wrong’ with that list of books he’s proudly (?) not gotten close to finishing is that they’re more trouble than they’re worth. Well, one can argue with him about that–plodding Mann isn’t something of a pleasure to read? none of those books gains momentum satisfyingly enough part-by-part to keep going??–, but, according to the criteria that Franzen actually admits to, ‘experiment’ itself is not the problem with every one of those books. (–length, for one example, is – a stupid criticism, for sure.)

Instead of looking at the disregard of good books as a whole, in order to reject its values as a whole, look for a moment at the value contrast itself between the virtues of Toil and Pleasure. You might love books that are Difficult Indeed–but are there no formally playful texts that you arrogate to yourself the privilege of unpretentiously denouncing for being “repetitive, incoherent, and insanely boring”? Is there no ‘classic’ that you quit on for being more trouble than it was worth?

Franzen’s owning his self-righteousness; the argument that he’s smuggling accumulation apology, like Davey Brooks and Tommy Friedman, is tilting at red herrings.

I don’t think Franzenfreude is “jealousy” (though maybe there’s that, but, critically, so what?); I think it’s obedience.

ok! Who is Chris?

So J-Franz says 140 or so anti-Twitter words, *potentially* taken out of context — assertions that would require an essay to unspool his complete opinion, and a blogger/writer posts it on her blog, which is linked to and discussed by bloggers, writers, readers, haters, and twitterers, which is then commented on as though the Holy Mount hath trembled with a serious pronouncement compelling comment from all. What I mean to say is: HOLY COW, people. I mean, people deanthropomorphize to pirahna and treat Franzen like a Holy Cow they shred to bone whenever he wades into the public stream. Each time pirahna people do this, they feed the J-Franz they mean to devour. J-Franz also says in a self-effacing way, that he seems “to have some small gift for offending people without intending to.” How true! Note that he also purportedly said an interesting thing about writing that’s gotten no play, championing writing as its own reward: “Not to be 1970s about it, but the process is more important than the product…It’s about the happiness of having a story to tell.” Writing As Own Reward, however, is not a company, not a brand, not a dot com, and therefore there’s no major response when he floats this idea, which all writers published or not can probably get with, except for those for whom the work is a vehicle for dispersing that all-important meme known as their name.

People talk about process-as-opposed-to-product all the time. This talk isn’t a “shit-storm” because there’s not much resistance to the sense that in process-as-opposed-to-product inheres vitality. Franzen’s remark – this one – about “happiness” simply isn’t controversial. You might get people vigorous about whether process-without-product is a coherent idea–or a useful antiphilosopheme–, or whether Franzen deserves “happiness”, but people love to curate their processes.

There’s two Franzen arguments that’re yoked together in the blogicle: ‘140-character units don’t admit of nourishing or even reasoned interaction’ and ‘difficulty indicates that something might be Wrong’.

Leave aside the pseud use of “pseudo-intellectual” and middlebrow revenge of “middlebrow”. Do you think that Franzen is part of a War on Experiment?

You know, I am unsure if you are the same deadgod as before, because *before* I used to read your posts and want to get to the end. An effective argument makes someone actually want to hear your argument. I begin reading a paragraph and my brain auto-tunes out. It is intelligently incoherent-clarity at its best. And it has nothing to do with the post being “too smart”, because right now I am reading an essay by Werner Heisenberg on Quantum Theory and the Structure of Matter and I can actually finish the paragraphs and understand it, you know? And not to say I don’t understand you… but I don’t *want* to understand you? Get it?

I understand that you’ve responded to a post that’s in direct and calm response to earlier remarks (and to their context on a thread) with a weirdly personal assertion of not having read or “*want*[ed]” to read that post.

(I, anyway, am interested in your perspective, but not in how “smart” you are. It’s odd to me that you’ve exposed these feelings to the world.)

Concerning your pained sense of ‘incoherence’, maybe other readers are interested in what you *want* to understand, but if you do *want* to understand the post you’ve replied to, here’s a paraphrase:

Eyeshot says that Franzen “purportedly said an interesting thing” comparing “process” and “product”, a slightly old-fashioned way of talking about making (especially making art), and points out that there’s been “no major response” to this “interesting thing”. I think that’s because that “interesting thing”, while “interesting”, isn’t at all controversial. I also wonder what Eyeshot thinks of the gist of the blogicle, as opposed to the fact of Franzenfreude itself.

What do you think of Franzen’s conflicted relation to ‘difficulty’ in fiction, and of the point he would make in aversion to twitter?

did you guys know that perec is hungarian for “pretzel”? as in, “Aztán jött csak a perec, a roppanós, vékony burkolat alatt a még gőzölgő, de szülői tiltás esetében is még biztosan meleg, mindennél puhább, fehér mennyország.”

which roughly translates to “Then came the only pretzels and crunchy, thin coatings under the still steaming, but also for parental prohibitions certainly still warm, softer all-white heaven.”which is the most beautiful thing i’ve read online today, and which would not be out of place in an oulipotext. also, who else thinks that georges perec looks like an artsy-fartsier bob ross? hands up.

Who cares if the guy doesn’t like Twitter? Twitter is not half as cool as people make it out to be.

This is just such a misinterpretation of Franzen’s original article. I read it in its entirety and I have to say those quotes are taken out of context, and most of them were made in an ironic or sarcastic manner. Please, anyone reading this, just go read it yourselves. If you do you will see that it is a very open and intensive look at the concerns of writing and publishing complex novels. He never says he commits to his Contract model, he claims to be both, and that they are not really definitive catagories but models to work with in a particular discussion. Also, he assigns Contract to mother because as he states, it is how his mother really was. His concerns with social media do not seem at all based on a paranoia of constrictive mediums. Twitter is not really a format designed to help users create beautifully spare statements that could be deemed a ‘constraint-based performance’, it is more something that enables anyone to tape up a quick comment about their hair or amazing tacos (both very frequent topics). I mean, not that there are not any clever, beautifully written tweets, but it is not something a novelist would be daunted at for those reasons. More the exposure and overwhelming constant stream of personal information and queries. Frazen is not at war on difficult novels, he wrote that one because he recieved a great deal of emails criticizing his for being too difficult.

[…] the blog, to excoriate Franzen for his shortsightedness. HTMLGIANT’s Roxane Gay and A.D. Jameson unpacked the quote and revealed a narrative similar to the one that’s been dogging Mitt Romney throughout this […]