Winter 1974, The Nail Bombs

Here’s something to keep in mind if you happen to be in Michigan next February.

Here’s something to keep in mind if you happen to be in Michigan next February.

On February 17, 1974, at a VFW Hall in Grand Rapids, Michigan, The Nail Bombs played their only show. They played for 11 and one half minutes. They played three songs. There were 19 people in the audience. All 19 started their own bands within two weeks of seeing The Nail Bombs play. Shows played by the bands formed by the 19 people who saw The Nail Bombs play inspired more bands. Those bands inspired more bands. Those bands inspired more bands. Thus, The Nail Bombs are an index case of much of the Midwest’s punk rock scene. (Sure, The MC5. Sure, The Stooges. But remember: with music, multiple ears are available to be infected, and multiple strains infect. The Nail Bombs were a strain. An powerful strain.)

No one knows who The Nail Bombs were. No member of the band has ever stepped forward and said, “I was a Nail Bomb.” No one has even attempted to do so as a hoax. They never recorded a record, or even made a little demo. There was at one point a tape of the show—the only audio evidence of the existence of The Nail Bombs—but it has been lost, and now there remain only some fragments of a transcript. (Fragments will appear at the end of this post.) READ MORE >

on shit

In the comment fields of life, there are no on & offs. There is no accept & delete. There is no excess & there is no restraint. Or maybe there is. Certaintly there is access. There is willingness & unwillingness. There is acknowledgement & avoidance. Engagement & disengagement. Inclusion & occlusion. There is hi & goodbye. There is yes & no. There is a river & there is a storm. There is water either way.

Because there are also maybes. There are I’ll consider its. There are that’s a fine points & what else have you got to says. There are I respectfully disagrees & there are I need to think about its. There are apostrophes taken & ignored, acknowledged & untaken. There is a wealth of unexplored landscape. There are loops & holes & loop holes & there are twists & turns & twirls & I dunnos. There are especially I dunnos. A succession of them, like a foolish parade that swallows itself in a smatter of red.

Apology is not a precondition of saying I dunno. “I dunno” is full of flavor & sometimes vigor & definitely spice. Some say opera, others say life. Some say private & some say public. Some say pirate, others say privateer. Whatever the sphere, it’s been made clear, we are all a little less than godly. We are shit, gaudy at best & at worst we are naked.

Maybe that’s not right. Maybe at best we are naked.

The weird thing is, when I look into the night, I hope to see satellites, but all I see is stars.

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#9)

BE SKUNK

by Gary J. Shipley

***

You got to be always skunk. There’s fuck all else to say – it’s the only stink there is. How else you gonna save yourself from the weak-assed perfume of just being okay, if you can’t stink it up more than them reekers too afraid to reek of anything?

What genus? Spotted, hog-nosed, hooded, any one’ll do. Just be that cunting skunk!

And if it happens, and it will, that you stink so good and proper people reckon you ambrosial, ask around for someone with a nose for anal air, death-row inmates, ambulance men, porn stars, plastic surgeons, any fuckwit with a voice, and ask them what it is they cannot smell, and the death-row inmate, the ambulance man, the porn star, the plastic surgeon will give it to you straight: “If you’re going to smell you might as well really stink like shit. Or else risk not being smelled at all, so go be skunk, skunk yourself the fuck up! And don’t stress the genus any, spotted, hog-nosed, hooded, malodour is where it’s at and always its own reward.”

***

![]()

I imagine ol’ raisin-nuts Baudelaire turning slowly yellow, his tits in a sack, his liver like a pockmarked turd, and I long to save him from all kinds of intoxication. I want to preserve him for unborn generations, who will recognise him not by sight but by the cut of his scent, a scent I’m proud to have initiated and prouder still to spread.

I imagine ol’ raisin-nuts Baudelaire turning slowly yellow, his tits in a sack, his liver like a pockmarked turd, and I long to save him from all kinds of intoxication. I want to preserve him for unborn generations, who will recognise him not by sight but by the cut of his scent, a scent I’m proud to have initiated and prouder still to spread.

![]()

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

December 17th, 2013 / 11:06 pm

25 Points: The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics, 4th Edition

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics, 4th Edition

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics, 4th Edition

ed. Roland Greene, Stephen Cushman, Clare Cavanagh, and Jahan Ramazani

Princeton University Press, 2012

1680 pages / $49.50 buy from Amazon or Powell’s

1. After graduating from college and while in the process of applying to MFA programs, I bought a copy of The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics having come across it in the discount bins of a book retailer down at the local strip mall hell lost somewhere between the suburbs of New Jersey and the rest of Southern California.

2. This was the hardcover 3rd edition published in 1993—previous editions appeared in 1974 and 1963.

3. Out of a total 1100 articles, the new paperback 4th edition presents 250 “entirely new” entries.

4. The Encyclopedia is what’s commonly referred to as a desk reference, i.e., it’s handy to have round.

5. With my 3rd edition I set out to learn EVERYTHING about the reading and writing of poems.

6. I’ve found this a daunting task. Nonetheless, my 3rd edition has been well used over the years.

7. It is a little geeky feeling—but nonetheless stimulating!—to pour over entries, allowing various elements of chance to guide where your floating interests and eyes may take you.

8. A Bibliomancy Tool: righteously applied in the proper MFA program deconditioning environment it just might save a young budding poet or two from the curse of professionalization. Or else it will studiously assist in that very further professionalization.

9. Five types of entries are included: “terms and concepts; genres and forms; periods, schools, and movements; the poetries of nations, regions, disciplines, and social practices such as linguistics, religion, and science.” These “are provisional, and many items could move among them.”

10. “A large number of entries are written by scholars of poetries other than English—a Hispanist on pastoral, a scholar of the French Renaissance on epidexis, a Persianist on panegyric.” READ MORE >

December 17th, 2013 / 6:35 pm

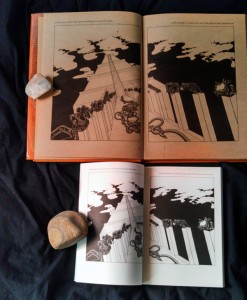

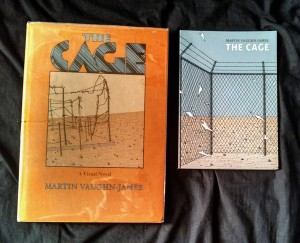

An Odd & Enigmatic Abstraction: Martin Vaughn-James’s THE CAGE

The Cage

The Cage

By Martin Vaughn-James

Coach House Books, November 2013

192 pages / Buy from Coach House Books

In November of this year, Coach House Books released a new edition of their seminal 1975 graphic work, Martin Vaughn-James’s The Cage. When I found this out, I was astounded. I’d been singing the praises of The Cage for years, recognizing it not only as one of the most important (and accomplished) work of graphic fiction ever created, but also insisting upon it being one of the greatest books every produced. Upon its initial publication, there were only 1500 printed copies; beautiful over-sized hardbacks with heavy brown paper inside. The book is a monolith, an object. Just the visual presence matches the title: The Cage, the book, the volume, holds something inside, much as a cage does.

I discovered the book from Richard Kostelanetz’s Dictionary of The Avant-Gardes, a resource that I read from cover to cover, taking note, over the course of the several months I spent reading it, on everything I wanted to learn more about, to discover. And then I spent several months following up on everything I had noted, often not remembering anything about why I had noted a book title or an artist’s name down. I worked in a library at the time, so I would just request anything from Inter-Library-Loan that we didn’t have on our shelves. It was through this process that Martin Vaughn-James’s book came into my life.

I took it home from work and blew through it, realizing that it was doing something heavy, something that I had long wanted the comic form to do, to work with narratives in ways similar to, say, Alain Robbe-Grillet or concrete poets had done, but to make use both of words & images, sequencing and panel development: to open up the tools available to a visual artist who also has a poetic bent. The book accomplishes so much, and I soon became obsessed. I read the book several times while I had it, and then checked it out several more times throughout the year. I desperately wanted to photocopy it (as copies available online were far too expensive) so I could always have it with me, but the book was too big to reasonably photocopy into a facsimile-ish form. I tacked down the three other primarily graphic works from Vaughn-James, again through inter-library loan, and marveled at their contents, but knew that The Cage was his masterpiece. Eventually a copy popped up on the internet for a prize I could sort of afford, so I jumped at it and the book joined my possessions.

To publish this book again in 2013 strikes me as no inconsiderable feat–while comics have certainly gained a larger presence as a “true literary form” (or whatever) by now, most of the dreck that people applaud is, of course, parallel to the novel, “realistic,” though told with pictures in addition to dialog. The Cage takes the height of the 70’s delirious experimentation with form and content, and pushes it into something that, even now, speaks as something new.

As such, I’m pleased to now revisit the work, in two parts. First I will comment upon the initial 1975 release, that is virtually impossible to come by outside of the library at this point, and second, I will consider the reprint, which offers both new front-matter & back-matter, as well as a formally different content, comparing and contrasting the two.

A Note: All photos included in this post were taken on my cellphone and do not necessarily reflect either the colors or the image quality of the printed books themselves

December 17th, 2013 / 12:26 pm

a very short parable

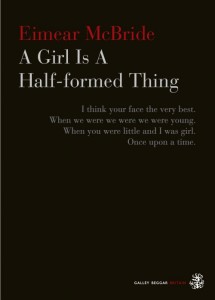

Girl Is A Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride

Girl Is A Half-formed Thing

Girl Is A Half-formed Thing

by Eimear McBride

Galley Beggar Press, 2013

240 pages / Buy from Amazon or Gallery Beggar Press

We were on the sofa one evening and I was typically glued to my book when my boyfriend leaned over and read aloud: Feel the roast of it. Like sunburn. Like a hot sunstroke. Like globs dropping in. Through my hair. Spat skin with it. Blank my eyes the dazzle. Huge shatter. Me who is just new. Fallen out of the sky. What. Then he rolled his eyes and asked me how the hell I was following that. The TV was on. The lamp was making a weird buzzing noise. The dog was loudly slurping her bits. To be perfectly honest, I’ve no idea how I was following A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing. The language is extravagantly jumbled. The pace is disconcertingly broken. The chain of events is peripatetic. Nevertheless, it had somehow managed to draw me in, to hold me. Each tiny sentence was blaring louder than the TV, louder than the buzzing lamp, louder than the slurping. And I understood perfectly; I knew exactly what was happening.

Last week, A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing won the inaugural Goldsmiths Prize for fiction. The prize, initiated by Goldsmiths University of London, is unlike any other I’m aware of in the UK. According to the official website, it has been established ‘to reward fiction that breaks the mould or opens up new possibilities for the novel form,’ celebrating ‘creative daring’ and ‘the spirit of invention.’ Eimear McBride might have instigated her debut novel intentionally for the prize, had it not been written almost a decade ago. The story of the book’s journey to publication makes the author’s victory all the more significant, albeit bittersweet. Originally rejected by publishers, presumably on the basis that it was too strange, too difficult, it was ultimately taken up by Galley Beggar Press, a small, independent publishing house. In the months which followed its release this summer, A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing has been reviewed to widespread acclaim. McBride has been variously declared a genius and her writing compared to James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.

The book begins with childhood in a gloomy and petty-minded version of rural Ireland. The half-formed girl of the title narrates. She is a reckless, fractious person, and the story is driven by her anger. She has no father to speak of and her mother is a pious, resentful woman. It is the strength of the bond with her elder brother that gives the half-formed girl her humanity. It is to him that every impassioned sentence is directed, even though it’s not with him that she is angry. Took me hot hand to the bathroom then and water on my face. Gentle wiping, saying there now it’s alright. Cleaned blood from me like I saw at school. Head back gulping the thickly flow. Now, you say, we’ll be good. Now we’ll do what we are told. Maybe she’ll forgive us if we’ll be good. Alright? We’ll be good now. After surviving a brain tumour in early boyhood, he is condemned as a dullard, his options stealthily shrinking as the years slip past. Handicap. Handicap. One from back gets the ball. Kicks and aims. It strikes your face. Bleared with mud. And knock you over. Laughter. Laughter. He is the character I cared about, the one I wanted to read on for. The story continues into the narrator’s twentieth year, her voice growing incrementally strained. The end is incalculably devastating.

I went to art school. (This may seem like a somewhat circuitous way of attempting to make a point but please bear with me.) I made colourful, wooden things, but my best friend made remarkably distressing video pieces. She’d perform actions that hurt, and film them. These actions weren’t necessarily physically painful, even still they proved excruciating to sit and watch. For example, in one piece, she used her chin to drag her naked body across a flat-weave carpet. In another, she manically licked tiny stickers off a white wall, and in another again, she bound her hand and forearm in elastic bands and then scrabbled to remove them using only the bound hand. Once I challenged her on what exactly was to be achieved by creating such unsettling work. So long as I made you feel something, she said. Feeling uncomfortable is better than feeling nothing at all. I recalled this conversation many times while reading McBride’s debut.

To say that I ‘enjoyed’ A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing would be lying. I thought it was a spectacular book, but it made me feel thoroughly horrible. McBride won the Goldsmiths Prize last week because, in the words of one of the judges, her debut is ‘boldly original’ and ‘will stimulate a much wider debate about the novel.’ It certainly encouraged me to contemplate the boundaries of traditional prose, and to reconsider the rules of grammar and punctuation. But the book’s greatest feat is that it outstrips the intellect and becomes foremost visceral in effect, a matter of the stomach and soul instead.

***

Sara Baume is a writer, of sorts. Her reviews, interviews, articles and stories are published occasionally both online and in print. She lives on the south coast of Ireland and can be found at www.sarabaume.wordpress.com

December 16th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

The Tales by Jessica Bozek

The Tales

The Tales

by Jessica Bozek

Les Figues, December 2013

76 pages / $15 Buy from Les Figues Press or SPD

Jessica Bozek calls her spurts of narrative in The Tales poems, but they aren’t, quite. Except for the sprawling middle section, Bozek’s short book is made up of justified blocks of prose such as this:

THE SAVING:

A FAIRY TALE

The loon’s lesson.

Now under funerary green, the citizens are cut off from the surrounding lands. A loon teaches them that they can dive down into their own small lake and come up in another lake. The cost of this transport is that all communication must happen underground.

The spurts trace the trajectory of someone called “The Lone Survivor” after a cataclysmic war known by its aggressors as Operation Sleep. The Lone Survivor makes his way into the world of the attacking nation, seeing visions of thriving life as he tries to hold onto his own past. From what I can see, he is eventually banished to a sort of reservation/museum-type installation, where reparations are attempted as time progresses. The political implications here are explicit, and welcome. But the value of the tales is mostly, I think, in their language, the way Bozek tells this story. Not through poems exactly. Nor, though, through fiction.

Of course, Bozek can call her work whatever she wants to call it. Poetry. Prose. Visual art. (The book is, indeed, beautiful, printed with all the white space that such short blocks of writing require, black endpaper, a red and gold Russian starkness on the front and back covers with a typeface of the same ilk.) But The Tales reminds me more of the hybrid work I am used to seeing from Tarpaulin Sky, in books like Kim Gek Lin Short’s China Cowboy and Sarah Goldstein’s Fables. In fact, The Tales earned its publication by winning the 2012 NOS (Not Otherwise Specified) Contest with Les Figues Press.

Bozek’s work here strikes me as one in a string of very compelling books of very short prose that are both language- and narrative- oriented. Such writing, I think, performs its work in a different space than poetry or prose. Where poetry, I would argue, creates much its value in the relationship between words, and more traditional fiction creates value in the relationship between paragraphs and events, Bozek’s hybrid vignettes seems to do their work between sentences, redefining causation, its images evoked with some clarity and yet set beside other images that would not “normally” come after them. The effect is a sort of circling-around, an attempt to penetrate the ineffable that is almost Zen-like. The shorts’ slow spiral tends toward some wordless meaning, I envision, drawing a picture in the readerly mind of a world with qualities so magical as to be literally inexplicable.

Part of this world is what we understand as dystopian, in the tradition suggested by the preface on “Operation Sleep,” by the book design, by words like “reparations” and “the State Museum for the Justification of Military Action.” But there’s something in the prose that is beyond words, too. In this vein—that, perhaps, of poetry—it is important to recognize that priority is given not to the narrative overall but to the effect of individual pieces. Symmetry is not a priority in this volume, and I am glad for it. Each piece stands for itself.

Which may be one reason why Bozek uses the word “poems” to describe what she’s written here. Another reason, I might guess, is her sheer personal investment in each piece, the compression of so much thought and feeling into so little language. The text of the book is followed by a full complement of back matter, sometimes outwording the vignettes themselves, as with one of the many with the title “The Lone Survivor’s Tale”:

I shed clothes in remembrance. The braided cables on my sweater unravel from the neck as I wind through the tree trunks, making a cyan tangle. When there is little left, I bite down to keep the cuffs.

Jessica Bozek explains, in her notes:

As glad as I was to have these iterations, I was even happier without them, for it is exactly the gaps in The Tales’ information that make it so compelling. The book’s middle third, the only section written in what would seem visually to be more explicitly “poetic,” ensues when the Lone Survivor “unspool[s] the words of those lost.” Across a series of mostly blank pages are scattered fragments of images and speech, remnants of some mostly erased world. The blank, here, is visual. In the rest of The Tales, it is conceptual, a blank in mental imagery, evoked in the way of the koan. So that we simply believe Bozek when she says:

I have begun weaving nests from the fallen hair on the floorboards and furniture. I leave these nests on high things outside. I want to be useful to the birds.

There is something more here, some ache, some weird impulse of energy and sadness toward a relevance that will never be relevant, not even to the few birds that remain to the Lone Survivor as companions. Not to mention the sheer image of a nest of fallen hair, wispy and whisked away in seconds by the wind.

But then, again: it doesn’t sound as good when you try to explain it. Which was why I was so happy to let Bozek’s Tales just breathe.

***

Dennis James Sweeney‘s recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Fractured West, Sundog Lit, Whole Beast Rag, and Word For/Word. Find him at dennisjamessweeney.com.

December 16th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Some Recently Acquired Reading Materials

Note: This is a small handful of books that I’ve either recently enjoyed or merely received in the mail, a more extensive review is probably in the works for a few of them, but for the moment I wanted simply to list the things themselves with notation where it seemed apt.

***

1. APOLOGY Magazine #2 I actually wrote the magazine’s editor Jesse Pearson about this one because I’d read that in the first issue they featured a Frederick Exley piece and that made me very happy. He was kind enough to send me the second issue and I’m planning to review it in a similar fashion to that tome I wrote about Out of Nothing, as these two things (Apology/OON) are some of the most exciting printed literary journals/magazines/etc. I’ve come across in quite some time. #2 features work from noir master David Goodis, as well as an interesting photo/essay from Richard Kern; and hijinks from Tim Heidecker; work from Steven Moore, Jerry Hsu, Anthony Berryman, and many others. I love the way this magazine feels very much.

2. Gigantic Failures by Mark Anthony Cronin. I bought this collection of short fiction (Disconnected Stories, the cover reads) awhile ago because I’d read a bit of Cronin’s work here and there online and was curious about the effect of one continuous block of his headspace. I was not disappointed. This is probably my favorite collection of short fiction put out by a small press this year, and reading it I was reminded of a younger version of myself voraciously reading through Jesus’ Son or The Big Hunger. I spoke with Cronin once about his appreciation for P.T. Anderson and since then can’t shake the notion that the absurdist-yet-highly-emotive world depicted in these stories connects easily to the fragments of a Magnolia or Boogie Nights. I fucking love this book. Amber Sparks, another author of a fascinating recent collection May We Shed These Human Bodies, had this to say “’The Man’s name was erased, totally forgotten. He became something beyond himself: a sermon given unto the world…’ Make no mistake: Mark Cronin has given us a collection born of myth and archetypes. Despite the modern settings, despite pop culture references sprinkling the stories, despite the piles of Walmarts and McDonald’s and AK-47s—these are stories that get at the heart of very simple, age-old truths, and the dream of what it is to be human in any time.” An excerpt was published at Volume One Brooklyn, and you can order the thing here.

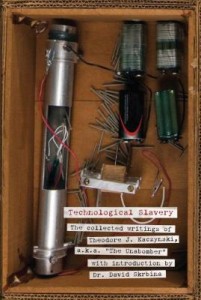

3. Technological Slavery: The collected writings of Theodore J. Kaczynski, a.k.a. “The Unabomber” introduction by Dr. David Skrbina Over the summer I had the immense pleasure of reading Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, and as a result have since kept my eye out for the occasional potentially-fucked narrative pressing the reach of reality that much farther. For awhile I was convinced there was something deeply profound in the connection between the Beach Boys’ Dennis Wilson and Charles Manson, and as a result purchased Wilson’s solo record and spent several weeks researching that element of the Manson ordeal. I came up with very little, but that isn’t really the point. Lately, a research obsession has been Kaczynski, and it’s largely due to my ignorance of the trajectory of his life thus far. When I was younger “Unabomber” was simply something people said when you wore a hoodie up and a pair of sunglasses, but since then I’ve realized that Ted Kaczynski is easily one of the most striking and disconcerting figures America’s ever seen—akin to Howard Hughes, I’d say, or the entire Kennedy family and all intertwined in their narrative rolled up into one man. Entering Harvard at sixteen, he then went on to become UC-Berkeley’s youngest professor before entering the woods to eventually embark on a mail-bombing spree that baffled the country until his “manifesto”—featured in this volume—“Industrial Society and Its Future” was published by the New York Times and a family member noted his writing style and he was locked away. He’s still alive, and recently sent his address in prison to the Harvard Alumni Association along with a list of accomplishments including his prison sentence. All that aside, because the list of Kaczynski’s criminal charges isn’t nearly as fascinating as the rest of his life, I bought this book because it felt like a source of information regarding our world that won’t even be considered for years to come. I think of entire college classes devoted to studying the Nazis in Germany in small Midwestern Universities and the prospect of this happening in 1950 being completely preposterous. I think of years to come when entire disciplines will exist devoted solely to the analysis of the Zapruder footage, say. I applaud Feral House for publishing this and other highly important titles. I am very excited that I as a living human animal am able to read this sort of thing without being arrested or something and that information is out there for us if we desire it, I dunno. I’m an idiot.