Artists, Eccentrics, Solitaries, and Saints:

On László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below

Translated from the German by Michael Hulse

Excerpts from Seiobo There Below translated by Ottilie Mulzet

This article on László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below, a novel just released from New Directions Publishing, originally appeared in German in Die Zeit on September 2, 2010, and its translation was commissioned and published by Music & Literature Magazine on the occasion of their second issue, devoted entirely to the creative cosmos of Mr. Krasznahorkai. This special issue is available for purchase through their website. You can also read an interview with M&L editor-in-chief Taylor Davis-Van Atta here. Follow the editors of Music & Literature on Twitter at @musiclitmag and @CWTParis.

***

These stories are about the sacred. Their high artistic character is not in question for a single moment: the flow of the sentences, frequently continuing over pages and broken up only by commas, is captivating; the stories’ forceful progression toward the moment when the sacred appears is masterly; the connection of the separate sections by a half-concealed group of motifs and their arrangement into a Fibonacci sequence are irresistible.

As if this achievement were not enough, after two or three stories an unnameable, haunting quality, beyond all the beauty of mere appearance, emerges from the aesthetic pleasures offered by Krasznahorkai’s unusual prose. We sense how the stories challenge us as readers; we begin to argue and debate with them. Are they right, or are we? “They” are the Russian Orthodox monks under the spell of icons, the Japanese Buddhists under the spell of a Buddha statue, the despairing Westerner unexpectedly under the spell of a Renaissance Christ. With Krasznahorkai, something has returned to art that was taken for granted and considered essential by Dostoevsky, and that has since then become more than a little diluted: the question leading toward the truthfulness of life.

Krasznahorkai brings his enlightened, relativist present-day Westerners, alienated to a greater or lesser degree, face-to-face with the absolute demands that the sacred makes of existence. The medium through which the sacred speaks in his work is the sacred art of the past, approached in stories that, by the author’s account, often have an autobiographical basis. Readers who may themselves be indifferent to religion will not find themselves repelled by this book, with its breathtaking diagnosis of the times. For Krasznahorkai is no preacher: the dimension in which he works is one of questing, inquiring, doubting. Any overweening earnestness is undercut with the irony that accompanies his often eccentric seekers on their path. And he evades the greatest danger of all, inflated pathos, with the most surprising of his stratagems: while he writes of art purely as an expression of the sacred, he does so in the unemotional key of a scholarly expert discoursing on the technical aspects of art history. Hence the Russian icons are, on the one hand, windows through which there shines a world beyond this one, and through which we may gain visions of the hereafter, yet, on the other hand, the religious narrative is directly confronted with a strikingly well-informed art-historical essay on the traditions and techniques of icon painting.

The luminous inner view and the profane external perspective of the holy are assigned a particularly convincing opposition in the story “He Rises at Dawn.” It describes the work of mask-carver Ito Ryosuke over a period of almost two months completing a Hannya mask for the Noh play Aoi no Ue. We witness every one of the minute steps in this procedure, in great detail and with atmospheric intensity, from the transfer of the stencil lines onto a piece of hinoki cypress wood until the completion of the masterpiece, which marks “[that] his hands have brought a demon into the world, and that it will do harm.” For his work, the carver withdraws into a wooden box he has made, to have perfect silence and seclusion. And yet it is not altogether certain who exactly is performing the work. For the carver does not think or plan anything; “within him there is no desire for the exquisite”; “his head is as empty as if he had been stunned by something, only his hand knows, the chisel knows why this must happen.” Only his hand—and his eyes. Again and again, he holds the mask-in-progress at arm’s length, comparing it with the stencil and with two photographs inside his work box: “this is the model, the ideal to be sought, this is what he must, in his own way, be equal to.” A time comes when his hand and eyes are no longer equal to the task unaided, and he lends support to his eyes with a “system of mirrors,” tilting and revolving mirrors which he installs around the box.

This gaze is contrasted with the external, intellectualized perspective of Western visitors, who pester the carver with “dreadfully tactless questions.” The Westerners want to know “what is the Noh, and what is the meaning of the hannya-mask, and how can there be ‘something sacred’ from a simple hinoki tree.” To the carver, their interrogation is a confusing tangle of questions, to which he can only stammer the briefest of replies: “…he does not occupy himself with such questions as what is the Noh, and what makes a mask ‘spell-binding,’ he merely occupies himself with doing the very best he can within the limits of his abilities, and with the aid of prayers recited secretly in shrines, he only knows movements, methods of work, chiseling, carving, polishing, that is to say, the method, the entire practical order of operations of tradition, but not the so-called ‘big questions.’”

In this way, the story reflects a certain polarity of East and West, at once steeped in the ethnographic nature of a craft and at the same time religious. The hand and its unconscious actions appear in opposition to the head and its questions about meaning; we find here the contrast of intellectual reflection and the external reflection from the system of mirrors. Indeed, most of these stories revolve around fundamental issues in philosophy. One of Krasznahorkai’s protagonists, at loose ends, attempts by a superhuman effort of the will to see the Acropolis on a hot summer’s day. But he sees nothing at all, blinded by the glaring sunlight and his own sweat, and at the end of the story he decides to return to a group of Athenian friends who have renounced all strivings of willpower and individual endeavor and simply do nothing all day.

The key philosophical motifs in these stories are of being overwhelmed, beaten down. Of one character’s response to an angel in an icon we read: “almost immediately at the sight he collapsed.” Of Baroque music: “it subdues one, breaks one’s heart to bits, knocks one to the ground.” A visitor to the Alhambra is “is so stunned by the beauty, by this beauty that is so, but so unbelievably beautiful that he thinks he is struck by vertigo,” where “a truth never before manifested reveals itself.” And a museum attendant who has been devoting his entire attention for decades to the Venus de Milo is “mesmerized,” “feet rooted to the ground.”

Krasznahorkai does not shy away from superlatives when he aims to convey the presence of the “celestial realm.” But, despite the philosophical appurtenances and the essayistic appearance, these stories are not sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought. For the concepts and superlatives are no more than buoys bobbing on the mighty current of Krasznahorkai’s prose. This musical river of language is the true event of this book, and is overpowering in itself. The current lifts up the reader, drags him down, catches him in whirlpools, is caught still, races across rapids, and with all of these qualities generates an experience that bars us from any distanced reading of the stories but forces us to live at the most intense pitch. It is impossible not to identify with these lonely, despairing, tired-of-life or just plain eccentric characters led by Krasznahorkai toward their moment of truth. We are drawn so close to them that it continually astonishes us when we realize that the stories are told not in the first but in the third person.

Of course, what we see here is yet one more balancing act by the great storyteller, László Krasznahorkai: just as he can be essayistic without slipping into didacticism, and emotional without turning bathetic, so too he remains wary of assigning the central position to his solitary and despairing characters, reserving that place to the current that tears everything with it—in one moment narrative, in the next meditative and interpretative—to the current of his prose.

***

Andreas Isenschmid has been editorial director at Schweizer Rundfunk, head of Literaturchef der Weltwoche, literary editor at the Tage-Anzeiger, among other distinctions. He now writes for the Hamburg ZEIT and is a critic on the program Kulturzeit.

Our Prime Vibratory Antennae: A Conversation with Will Alexander

Will Alexander is a visionary and ecstatic writer whose most recent book is Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat: Essays, Prose Texts, Interviews and a Lecture, published by Essay Press. Other recent books include Kaleidoscopic Omniscience, Mirach Speaks to His Grammatical Transparents, Inside the Earthquake Palace and Compression & Purity.

Will Alexander is a visionary and ecstatic writer whose most recent book is Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat: Essays, Prose Texts, Interviews and a Lecture, published by Essay Press. Other recent books include Kaleidoscopic Omniscience, Mirach Speaks to His Grammatical Transparents, Inside the Earthquake Palace and Compression & Purity.

Alexander writes in “Spirit and Practice,” an essay from Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat, “Being menaced by consciousness, the poet finds that the magnetic inscription of words on the page is only part of a continuum. One’s every movement, one’s every despair, is empowered by a wild illuminant rush which burns at the base of one’s character. This is the praxis of spiritus, the praxis of breath, in the simultaneous realms of the diurnal and the oneiric. This constant awareness seems always empowered by a surreptitious sun emitting its power through the aural canals. And the raw material of life is always transmuted by these aural rays. And because of the fire at this sensitive level, one is continuously placed in temperamental combat against the quotidian carnivore, against its reflexive muscle of fact.”

Alexander’s prolific body of work radiates radiance and exemplifies a type of luminosity that seems extremely rare in this world. His verbal flights soar far above the quotidian to a place of vision. Alexander’s use of language is alchemical and talismanic, relating to mental travel through the expansion of awareness and the unfolding of alternate modes of perception. I’d like to thank Will Alexander for providing a way to see, a way to facilitate the envelopment of energy, and for engaging me in this discussion.

***

Chris Moran: Your writing often takes me to remote sectors of the psyche where the language of poetry is not the exception but the primary ruling principle. This has something to do with your expansive vocabulary, which often incorporates the language of astronomy, geology, mathematics, alchemy, botany, mythology, geography, and many other fields. Your use of language goes far beyond the ‘neuro-linguistic programming’ that can stifle the imagination. It feels akin to scrying, and I sense there is something deeply alchemical going on. How is this lens of perception attained, where poetry is indistinguishable from philosophy? Also, do you see language as divinatory?

Will Alexander: When language is felt as a living intelligence it quickens as one internally develops. One can feel its spontaneity like a drone in one’s system. For me, it magnetizes itself to different genres, and to various branches of knowledge. All knowledge springs from the 26 letters of the alphabet, being a poet I am naturally magnetized to its spectrum. Being free, I can range across its field of expression, which includes medicine, astronomy, botany, history, music, cinema, mysticism, architecture. It’s an infinite and evolving list. I’m picking up murmurs all the time. In this sense as I write language takes on an alchemic personality, like an Amazonian flooding replete with the ferocity and power of aboriginal presence. A power yes, but not unlike the mathematics which the old Kemetians used in constructing the pyramids. A living word is not unlike a living number creating a pulsing construct, be it a piece of writing or a pyramid. In this sense creative language is not adverse to philosophical utterance of the vatic.

CM: It’s not unusual to come across words in your poems that I’m unfamiliar with, and many of your books feature a glossary. What you do reminds me of Hart Crane’s dictum to “create new words, never before spoken and impossible to actually enunciate.” This goes far beyond the saturation of elemental forces, as it incorporates planetary and cosmic energy. Where does this knowledge come from? Is it necessary to access alternate modes of perception in order for poetry to process knowledge, or for a poet to embody knowledge? How do you attain this multidimensional framework?

WA: I’ve been engaged in a praxis sustained across duration. I’ll call it in this context poetic yoga. I remain in poetic trance day and night. It is a living world. As I stated earlier the poetic is always murmuring to such an extent that I feel its palpable presence within me. It is a presence which was first introduced to me when I learned about circular breathing. When one can breathe through one’s medium to such a degree that quotidian distraction can gain no entry. One then embodies whatever one is writing on to such a degree that the specific nature of the subject at hand ignites from the root being engaged by the imagination takes on the tenor of the unexpected. The unexpected charged with magnetism which naturally attracts energies from what the Occidental mind calls the invisible. And it is by means of this invisibility that one can intermingle knowledges and poetically contact new lingual dimensions which ignite new synapse firings in the cortex, which can’t be predicted in an a-priori manner since organic creation carries spontaneous warmth as its resonance and by its very nature cannot be chronicled as one would abstractly add or transpose a superimposed structure replete with in-built boundary.

…….I am Paulina……

Lying in bed the other day and listening to Paulina Rubio’s sultry and filthy voice I felt suddenly (no, I knew!) that I could have written her songs and that she could have written my poems.

——Encrusted W/ Emeralds——Stinking Ditched——Boiling——

——I’m On The Back——Of An Elephant READ MORE >

September 24th, 2013 / 10:36 pm

A Close Reading of a Poem By a Girl

While being educated upon literature, one of the most marvelous assignments I received was to conduct a close reading of a poem of my choosing. Though 99 percent of the people who associate themselves with literature nowadays probably perceive poems as mere documents that they’re coerced to comment upon in workshop, I am mesmerized by beatific poems, and I believe each one necessitates thoughtful evaluation. After all, when you see a beautiful look by, say, Calvin Klein, you shouldn’t just mumble “Nice job, Calvin” and then zip right along to the next one — that’s inconsideration. What everyone should do is concentrate on the look exclusively in order to notice the particular shade of grey and the way in which the squiggly white stripes contrast those of the grey ones.

The same should be so for a poem.

The poem I selected to do my close reading with was Charles Churchill’s night. An 18-century poet who didn’t like gay people, Charles is often ignored, while poets like putrid pragmatist Alexander Pope are emphasized. But, really, Charles needs ten times the heed of Alexander, as Charles is ten times as terrific as Alexander.

For Charles, the greater public views the daytime as the place of hardworking humans and the nighttime as the space of a sordid species. But in his poem, Night, Charles says that daytime is much more foul than nighttime. Using heroic couplets, Charles explains why the daytime is contemptuous, calling its denizens “slaves to business, bodies without soul.” In contrast to the spiritless stupids, those who wander in the night have an “active mind” and enjoy “a humble, happier state.” Near the end Charles states, “What calls us guilty, cannot make us so.” While I concur with Charles that just because the 99 percent say it’s true doesn’t make it true, I don’t agree that the nighttime is so wonderful, as gay people go out at night a ton, and gay people aren’t a thinking bunch.

But Charles’s poem is still bold, bellicose, and abrasive, and all of those traits are laudatory, and, through my close reading, I became much better acquainted with them.

Also disseminating a decided amount of close reading are the baby despots of Bambi Muse. Baby Adolf did one on Emily’s “Presentiment,” Baby Marie-Antoinette did one about Edna’s “Second Fig,” and Baby Joseph did one concerning William’s [“so much depends”].

Close readings appear to be very vogue. So, having already summed up a close reading of a boy poet, I will presently present a close reading of a girl poet.

September 24th, 2013 / 1:29 pm

“Narrative Gold” — (In the Memoir Swamp) — Talking to Seattle’s Elissa Washuta

*****

*****

Rauan: why is most Memoir so bad, so boring (and in so many instances just a kind of “grief porn”)??

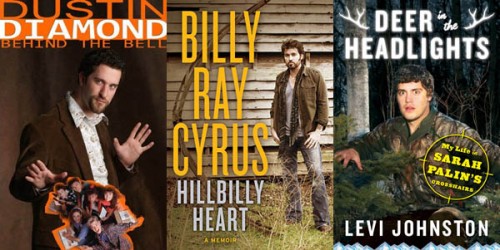

Elissa: Memoir is the genre most often entered by celebrities. It’s also full of books by people whose lives have been stricken by remarkable tragedies or circumstances that are marketable to readers hungry to know about other people’s lives. If we want to know about that secret wig that Andre Agassi wore for years during his tennis career, he’ll gladly sell us a copy of his memoir, Open. If we want to know how Dustin Diamond felt about playing Screech, he’ll give us an earful in Behind the Bell. Politicians use memoir to push their agendas; the infamous use it to set the record straight. Many celebrity memoirs are ghostwritten, and I get the feeling that the people on the covers don’t think much about craft.

Memoir isn’t working, I think, when the author has no ear for language, no eye for image, a limp voice, and an insistence upon a narrative arc that delivers an easy revelatory triumph at the end. In mediocre-at-best memoirs, the narrators balk when faced with the opportunity to tease out the most complicated tangles of their experience–sometimes, the revelation of their own complicity in what’s gnawing at them. That’s narrative gold in memoir: reading about a character with agency is much more compelling than reading about a helpless victim. I certainly do not wish to judge or take away from the lived experiences of the people who wrote the memoirs that I’ve found the most to critique in (including Prozac Nation by Elizabeth Wurtzel and Lucky by Alice Sebold), but in memoir, there’s a problematic tendency to close the gap between art and life that allows the most exciting work to take place.

I read and listen to (audiobooks of) lots of memoirs. I’ll listen to any memoir that Seattle Public Library has available. While I do think the memoir genre is full of duds, I’ve read so many thrilling, vibrant, well-written memoirs in the past few years, including Rat Girl by Kristen Hersh, The Guardians by Sarah Manguso, Confessions of a Latter-Day Virgin by Nicole Hardy, READ MORE >

First Study for a Long Walk: Castle to Castle

Lynn Xu and I are married, and we’re also poets. For the past year we’ve lived in an interdisciplinary residency in Germany, in a community of artists and all sorts of people we don’t usually get to hang out with: architects, new music composers, choreographers, filmmakers, even a chess Grand Master and a video game sociologist. Soon we will return to the States and to the small vacant lot in West Texas that we call our home. In order to continue conversations we’re having, and to drag art further into our life together, we’ve come up with a project called Architecture for Travelers. At its center is a collaboration with our friend Alan Worn, with whom we’re designing a house and a cottage where we can host residencies for creative people. There will also be poetry, photography, and a long journey involved. We’re not crowd-funding, but we are taking pre-orders for limited-edition photographs and books to help out with expenses. ( For more detailed info, visit our website.)

Beginning in November, I’ll spend a month or so walking 700 miles from my birthplace on Galveston Island to our property on Galveston Street in Marfa, sometimes accompanied by family and friends. Today Lynn and I went on a practice walk, and for the first time incorporated another aspect of the planned trip across Texas: taking photographs each hour on the hour (5 today, about 240 in Texas). We set out from our studio at the Akademie Schloss Solitude and four hours later arrived at Schloss Ludwigsburg. This is the second time I’ve traveled between these two castles on foot, the first was this past winter with friend, collaborator, and artist Charlotte Moth. Robert Walser wrote “A walk is always filled with significant phenomena, which are valuable to see and feel,” and both trips from Schloss to Schloss have lived up to this proclamation. During the first some of our ideas were dreamed up, and this time some details became clearer. Here are the five photographs from today’s walk, along with written sketches about our time on the road.

***

1.

We left at eleven this morning. Heading down the big hill Schloss Solitude sits atop, we could see the straight-as-an-arrow path we’d be following stretched out for six or seven miles, after which it disappears over a wooded hill. I turned around and photographed our starting point. It made me think of Wallace Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar”: “It made the slovenly wilderness / Surround that hill.” Despite a forecast of showers, the weather was perfect and the skies were blue and clear all day long.

2.

At the one-hour mark we were crossing through the outskirts of Stuttgart. There was some interesting architecture to be seen, but as the clock tolled the best thing around was a tree that Lynn spotted in a front yard behind a white picket fence. It was terrifying. It looked both totally out of place and too perfect for the suburban landscape. As we walked on, we talked about the best way to display the 240 photographs that we’ll have at the end of the Texas journey.

Birdwatching with Jonathan Franzen

I was between meetings with my editor and agent, walking down E 12th St. about to enter a cafe for an almond croissant, when I spotted a Columba livia (of the Columbiformes order, colloquially known by pedestrians as a “pigeon”) standing on the sidewalk gazing into the havoc of industry brought upon by humans, the good earth embalmed under slabs of concrete and funk. I always carry my binoculars, a moleskin, and one sharpened No. 2 pencil in my satchel. Did people stare at me as I stared at this fine specimen of urban worry? I could not tell. Peripheral vision, like 20/20, is overrated. Under the lens of my binoculars, past those of my unwittingly hipster glasses, through my cornea into the timeless cave painting of light on my retina, along my optic nerve like some whip of meaning, and into this very large head, I witnessed a stillness—enough to make one dry weep—unknown to our younger generation currently glued to various vapid interfaces with apps on their supposedly “smart” phones. From the ashes of Goethe and Heine, the timelessness of vision’s sad lament of nature could be felt in my bones, and jeans. I needed new pants. This diet was going nowhere.

okay, so, Franzen’s been toasted again:

“Every woman must decide how not to sleep with Jonathan Franzen . . . how best to escape his sexual clutches if (she) ever encountered him on the path that led to the nearest market town” —

(from The Toast)

“for he shall be riding on a white steed, and his right hand will bear no glove. When you see him, you must rush at him, and throw your kirtle over him, and hold fast to him –”

(from The Toast)

But is it funny? In poor taste?

click here to read the “Toast” in full

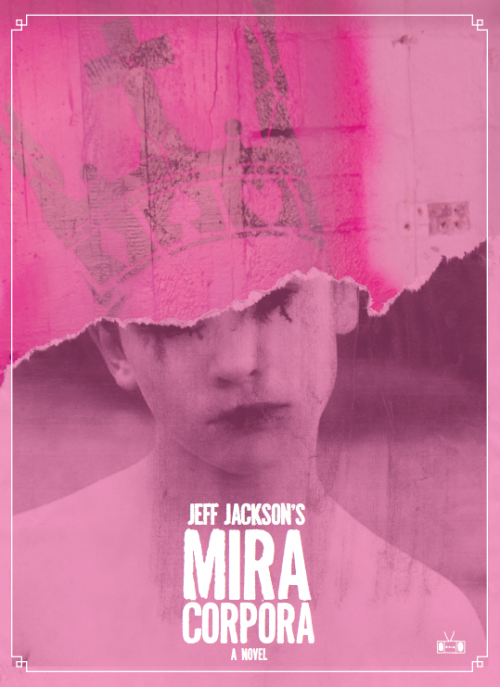

The Original Narrator No Longer Exists: An Interview with Jeff Jackson

Jeff Jackson is the author of the novel Mira Corpora, just released from Two Dollar Radio. He holds an MFA from NYU and is the recipient of fellowships from the MacDowell Colony and Baryshnikov Center. His short fiction has been featured in Guernica, The Collagist, the anthology Userlands, and performed by New River Dramatists in New York and Los Angeles. Five of his plays have been produced by the Obie Award-winning Collapsable Giraffe company, including Botanica which was selected by New York Times as “one of the most galvanizing theater experiences of 2012.” Of Mira Corpora, Don DeLillo says this: “I hope the book finds the serious readers who are out there waiting for this kind of fiction to hit them in the face.” And Dennis Cooper says this: “Jeff Jackson is one of the most extraordinarily gifted young writers I’ve read in a very long time. His strangely serene yet gripping, unsettling, and beautifully rendered novel Mira Corpora has within it all the earmarks of an important new literary voice.”

Michael Kimball: I’m curious about the way the title and author are presented on the cover. It’s not “Mira Corpora” and then “Jeff Jackson” as it is on the spine. On the cover, it’s “Jeff Jackson’s Mira Corpora.” It’s something I’ve only seen with movie titles, I think, and I’m wondering how you decided on that particular presentation.

Jeff Jackson: Two Dollar Radio was apparently inspired by movie posters when they came up with that presentation. There wasn’t any conscious strategy behind it other than to create something that stood out. I can see how it invites a deeper reading, though. Early readers have said the book’s prose has a cinematic quality (and I’m a huge cinephile) and putting my name before the title seems to reference that the narrator shares my name.

You might have read about the golden age of online book clubs, but have you heard that those genius kids at APRIL in Seattle are starting their own book club? You should click here and read about it.

You might have read about the golden age of online book clubs, but have you heard that those genius kids at APRIL in Seattle are starting their own book club? You should click here and read about it.

Sign up for $30 and get three sweet books in the mail over three months. Seattle folks: you can talk about the books with other attractive brains at the Frye Art Museum Cafe every month. You have to RSVP, so that’s important. The first book is our own Matthew Simmons’s excellent Happy Rock, and the meeting in Seattle is October 6th at 2PM.