I Am Prepared to Read Many More Novels About People Fucking

I haven’t read Sheila Heti or Ben Lerner’s recent novels, the impetuses for Blake Butler’s recent, anti-realism-themed Vice article, but I’d like to respond to Blake’s finely-written itemized essay, because I, personally, continue to desire novels written by humans, which relate, slipperily or not, to human reality—subjective, strange and ephemeral as it is–novels which deal with such humdrums as sex, boredom, relationships, Gchat, longing, and, beneath all, death. I want a morbid realism.

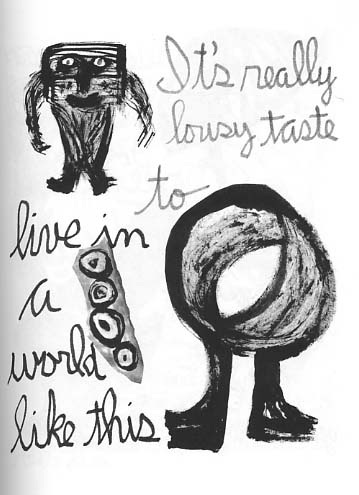

I agree with Blake that a reality show like The Hills and social media such as Facebook create stories by virtue of humans doing simply anything. The documenting, sharing, and promoting of mundane everyday human life is more prevalent and relentless than ever before. In this environment, literature (and movies) about humans (most controversially, about privileged, white, hetero humans) that presents everyday drank-beers-at-my-friend’s-apartment life, wallows in self-pitying romantic angst, and doggy paddles po-faced through mighty rivers of deeply profound ennui can potentially seem annoying, or boring, or shittastical.

DIED: Edward Archbold

On October 5, Edward Archbold, 32, won a live roach-eating contest at a pet store north of Miami, Florida. After his win, Mr. Archbold felt ill, began vomiting, and was taken to a hospital where he was pronounced dead. Other participants in the contest did not fall ill and did not die, suggesting that his death might have been unrelated to the large number of live cockroaches he consumed. Or at least that, for the larger percentage of us, the consumption of a lot of cockroaches is not necessarily dangerous. READ MORE >

How Not to Think: A Few Words

A year ago I was in Germany, alone and growing a beard—the only beard I’d ever had or since—for questionable and seemingly unironic reasons. I felt some prejudice, especially at the doors of clubs, of which I saw several facades but never an interior. I experienced some new forms of illness, peed on myself in a cab and bought an €11 plane ticket to Norway. I felt lost and rarely thought of death, and now my life has leveled out a bit. I live with my girlfriend and signed my first official lease on part of the second floor of a two-story house. I cook and drink American beers, plan my weeks around the presidential debates. Compulsive paranoia regarding the suspect preparation of cappuccinos has been replaced with making sure my clothes are off the couch and bills are paid. New fixations, too, have arisen: to map the narratives of my amaranthine nightmares, to parse the patterns of diffuse images of terror and decay that drift throughout my consciousness, to grapple with religion, God, the transmutation of the body and the limits of the human mind, the actual capacity of the thing and the shape of its components. Lately a vague sensation of erosion has begun to worm its way into my cognizant perception—a knowledge of mental illness, colors swaying into a kind of one color, that which contains every color and/or imageable, magmatic structure.

A year ago I was in Germany, alone and growing a beard—the only beard I’d ever had or since—for questionable and seemingly unironic reasons. I felt some prejudice, especially at the doors of clubs, of which I saw several facades but never an interior. I experienced some new forms of illness, peed on myself in a cab and bought an €11 plane ticket to Norway. I felt lost and rarely thought of death, and now my life has leveled out a bit. I live with my girlfriend and signed my first official lease on part of the second floor of a two-story house. I cook and drink American beers, plan my weeks around the presidential debates. Compulsive paranoia regarding the suspect preparation of cappuccinos has been replaced with making sure my clothes are off the couch and bills are paid. New fixations, too, have arisen: to map the narratives of my amaranthine nightmares, to parse the patterns of diffuse images of terror and decay that drift throughout my consciousness, to grapple with religion, God, the transmutation of the body and the limits of the human mind, the actual capacity of the thing and the shape of its components. Lately a vague sensation of erosion has begun to worm its way into my cognizant perception—a knowledge of mental illness, colors swaying into a kind of one color, that which contains every color and/or imageable, magmatic structure.

Still Life

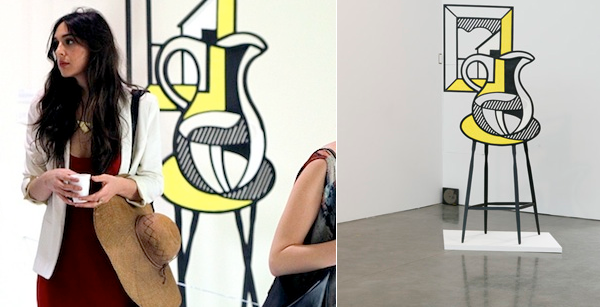

As Claudia of Bravo’s Gallery Girls stood in front of a Roy Lichtenstein still life, the base on which the jug stood — a cut-out sculpture (technically) rendered as a flat painting and oriented in unison with its counterpart behind it — was cropped off, so that the average unacclimated viewer, blockaded online in two-dimensions, would have thought it was merely a painting. In this world of illusion, of collapsible iconic space, one may also be drawn to Claudia’s beauty, the sides of her hair as curtains to the constant one-act play of herself. One night after work, scanning through my Comcast options — with that kind of defeated shameful complicity in television viewing — I settled upon this show, skeptically, as it had appeared on some bitch’s facebook timeline. It basically follows half-a-dozen women through their lives as they maneuver New York City’s gallery world. We see effeminate attitudinal men in rimless spectacles, often holding obnoxious dogs; women whose countenances have been stretched both severe and eerily frozen by plastic surgeries; the glass spiderweb of a cracked iPhone being cried into, inside a cab whose fare their father is, well, faring. I may have shouted at the TV and lowered my pants. I may have drank a bottle of wine. “My still life paintings have none of those qualities, they just have pictures of certain things that are in a still life,” says Roy concerning his less than palpable work. Implicit satire is the spoiled child of the homage. In the episode I saw, Claudia got upset with soon-to-be ex-bff Chantal — whose distant Xanax induced gaze reminds me of a Nebraskan horizon one can never drive closer to — for supposedly getting sick in Paris, causing her to miss out on some hefty electricity bills. We then cut to commercial: a woman riding a bike with a tampon inside her, smiling as if ’twasn’t there. Perhaps menstruation is the opposite of God. We pretend it doesn’t exist. I felt sorry for myself, and the dead author whose novel I was neglecting. Later that night, some claws came out at a table adorned with tulips, its still life barely noticed in the background.

Death By Subtitle: How Extravagantly Fallacious Subtitles Are Ruining Books

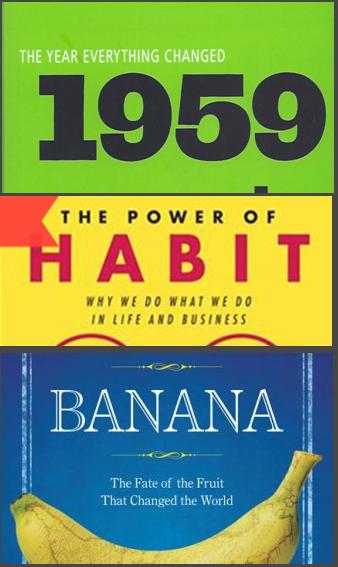

1959: The Year Everything Changed

Habit: Why We Do What We Do In Life

Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World

And now there’s Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How The World Become Modern, a book which, while very good, doesn’t live up to its subtitle. None of these books do. They can’t. Their subtitles are overly ambitious, promising that everything the reader has ever wondered about will be explicated in grand, enriching, yet academic detail over the course of the next 300 pages. Except this doesn’t happen and reader disappointment ensues. These books are all overpowered by their subtitles.

Greenblatt’s The Swerve is the history of a Latin poem, On the Nature of Things by Lucretius, which was lost ages ago and found in 1417. While Greenblatt’s love for this poem is clear and while he extols its greatness, he never comes close to explaining how the world becomes modern.

There are a few half-hearted attempts to justify the subtitle and a Malcolm Gladwell-esque idea that in history there are swerves, moments where everything suddenly shifts. (The key to having a Macolm Gladwell-esque idea involves capitalizing a noun then making it seem extremely important; luckily, Greenblatt has the dignity to avoid random noun capitalization.) Really, though, this book is the wonderfully well-researched history of Lucretius’s poem. It doesn’t have a lot to do with the entire world or momentous modernity. But if you’ve been keeping up with publishing trends, you probably already knew that.

No Tricks

Like many of us, I’ve read “On Writing” by Raymond Carver numerous times. It holds many useful ideas. There is a stage of our own creative writing. (I believe this phase usually arrives in the mid-20s, but possibly I am in error—perhaps it arrives after so many years of practicing the craft, not so much a writer’s age.) Either way, this stage involves reading copious interviews, craft books, and essays on writing, by writers. Apparently, as writers, were are seeking some golden ticket, some integral advice, etc. I believe most writers leave this period, and then, you know, write.

What is the most famous (or infamous) line from the Carver essay? No tricks.

“No tricks.” He says. “Period. I hate tricks.”

First, I like tricks. So what? Others have written the same. Second, Carver is wrong. He doesn’t hate tricks, he uses them. He especially employs tricks in the shorter form. Why? Because “tricks” are not tricks. Tricks are technique. Technique is important to the short story, very important to the sudden fiction, and absolutely essential to the flash fiction form. We flash writers have fewer words. We need artistry.

Let me show you Raymond Carver using some tricks. Read “Little Things” here.

OK, onward.

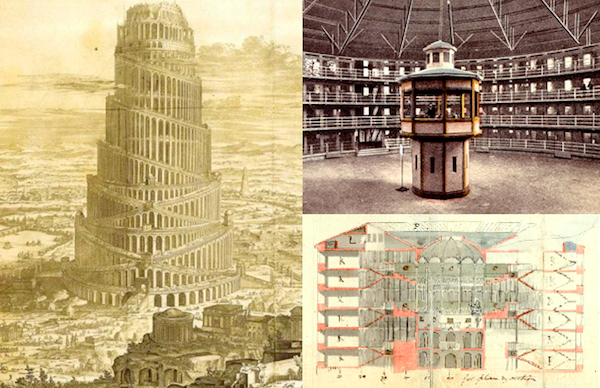

Babble on Babylon

“Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech,” says the ticked off voice from above in the Book of Genesis (11:7) — though modern versions prefer confuse to confound, retroactively auspicious, since Babel sounds like the revised “confuse” (bālal) in Hebrew — thereby scattering our tongues into various, um, babbles, from the harshest Cantonese, bluntest Ebonics, to the always DTF-French. Regarding the etymology of babble, “no direct connection with Babel can be traced; though association with that may have affected the senses,” attests the Oxford English Dictionary. Near bizarrely, the original English word for babble was babeln (c. mid-13th century), that helpful -n a kiss away from Babylon, just for funnies, where this all supposedly took place, meaning “gateway to God.” Early 19th century philosopher Jeremy Bentham conceives the Panopticon, an institutional building (usually prison, though also applicable to hospitals, daycare, etc.) in which authorities at an omniscient center have a 360° view of the entire perimeter. Mr. metaphor Foucault (in Discipline and Punishment, 1975) is moved by the idea of “permanent visibility,” a form of power whose construct was more imperative than its actually being possible: the prison guards, while having access to the sweeping perimeter could only look at one area at a time, their backs turned to everything else. The habitual possibility of being watched was just as effective as actually being watched. Hence, religion as security cam.