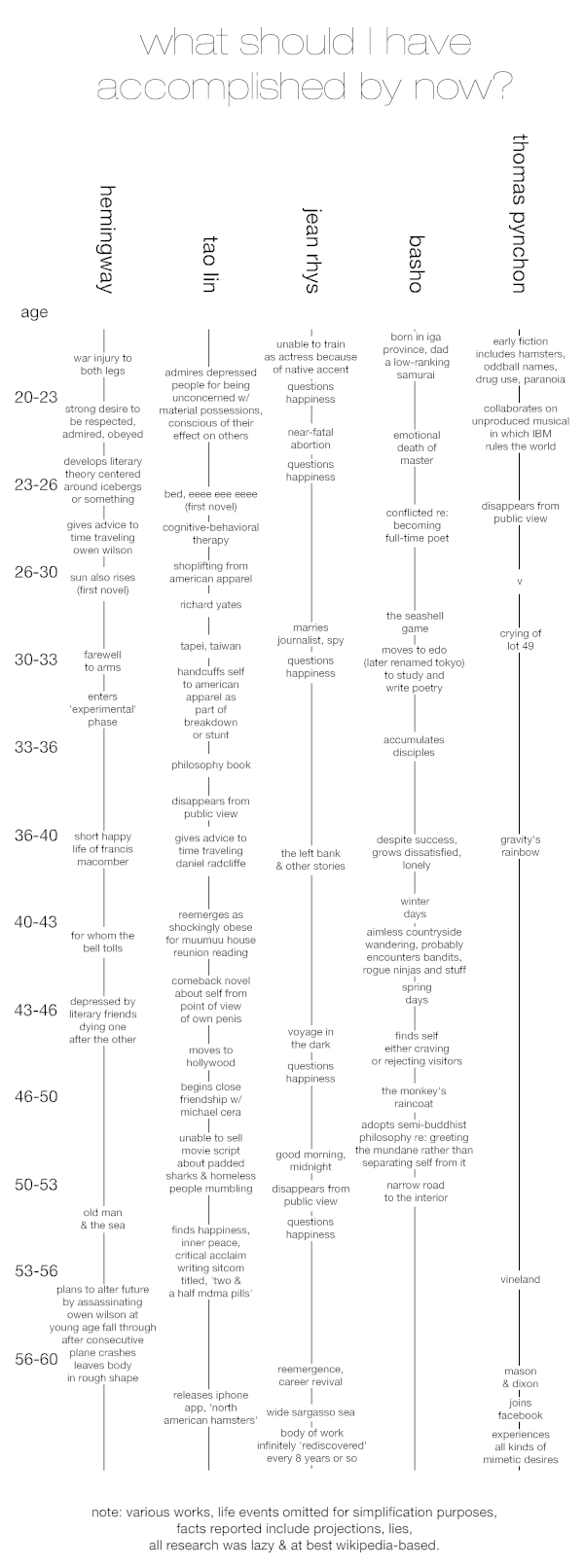

100 things to do when you have the time

“There are people who say, ‘If music’s that easy to write, I could do it.’ Of course they could, but they don’t. I find [Morton] Feldman’s own statement more affirmative. We were driving back from some place in New England where a concert had been given. He is a large man and falls asleep easily. Out of a sound sleep, he awoke to say, ‘Now that things are so simple, there’s so much to do.’”

—John Cage, Indeterminacy

100 things to do when you have the time

- Doodle. Look for new styles, new approaches.

- Draw a picture of a friend. See how many different ways you can do it, such as how few lines you can use.

- Recite something you once memorized: a poem, a song, a story, a monologue.

- Memorize something new.

- Write a review of something you like.

- Go over the steps in a procedure or a process.

- Explain to a friend a thing you know, or think you know.

- Write a song, or cover a song.

- List the projects you’re working on, or want to work on. Set a deadline for completing one of them.

- Review every thing that you’ve done in the past week, the past month, the past year, the past five years, the past decade.

- Reread your diary or journal. If you don’t keep one, reread old sent emails.

- Describe something in as many words as possible, then as briefly as possible.

- Make up a riddle or joke.

- Make a puzzle for others to solve.

- Play a Dadaist/Surrealist/Oulipian writing game, such as automatic writing, the Exquisite Corpse, the Cut-Up Technique, homophonic translation, lipograms, …

- Write a story or poem entirely in your head.

- Observe whoever is around you. Note what they’re doing.

- Observe how the energy levels in a room change over time.

- Perform John Cage’s “silent piece” (4’33”). Pay attention to both the aural and the visual.

- Perform random FLUXUS pieces, then try inventing new ones.

- List all of your interests. Prioritize them.

- Compose a view.

- Explore a texture (a fabric, a liquid).

- Examine a nearby text. Why is it the way that it is?

- Explore a space: a room, a building, a street, a city.

#THINGSIDIDNTTWEETATAWP

These are things I didn’t tweet while walking around AWP like a zombie (typos included):

Do As Franzen Does. Do What You Like

In some ways, we’ve brought this on ourselves; it is a slippery slope. First you wonder what Angelina Jolie had for breakfast because she was so great in that one movie or whatever and then you’re buying cereal and thinking, “Does Oprah eat Raisin Bran?” Eventually, you even start to give a damn about what famous writers think about the weather or, say, social networking, and someone like Jonathan Franzen revels in his dislike of Twitter and other means of social networking from his Important Writer perch and we respond because if Franzen hates Twitter does he hate us too? The angst is unbearable and yet it’s all sort of inevitable.

Franzen’s A Great American Writer and all but I don’t give a much of a damn about his opinions on anything (see: Edith Wharton obvi). Or I do. Is it really surprising that Franzen doesn’t care for Facebook or Twitter? His overall comportment does not suggest an affinity for the levity of social networking. I can’t really say I love Facebook, myself. It has become increasingly hard to make sense of the interface and I keep getting invited to parties and readings in Bali and Temecula and I don’t live in those places so the experience is, at best, fragmented. At the same time, I don’t need to proselytize my dislike unless I’m on Twitter. Who cares? My opinion doesn’t matter nor does Franzen’s, though he is Very Fancy so in the calculus of mattering, his irrelevant opinion is less irrelevant than mine. Math.

J. Franz talking smack about Twitter, though, thems fighting words.

Power and the Glory by Graham Greene

God and man? But isn’t it searching in a dark bar at three a.m. for a hipster magician that isn’t there? Yes. No. Maybe. If you asked Graham Greene what he would take to the desert island, he would say, “Sunblock, three ribbed condoms, a tube of camouflage, the bible, and Power and the Glory.” It was his favorite book. History lesson: While President Calles is sane on all other matters, he completely loses control of himself when the matter of religion comes up, becomes livid in the face and pounds the table to express his hatred. You can trust God to make allowances, but you can’t trust smallpox, or men. The dentist metaphors are supposed to be about the “teeth” of your beliefs—without them you only eat mush, or a stale BRAT meal: bananas (“ripe, brown, and sodden, tasting of soap”), rice (an annual plant), applesauce (favored by children and criminals), and toast (brimstone bread). Miracles, do you believe in them? Yes, but not for me. In his 111th collection, Graham Greens’s characteristic M.O. is intact: casually enjambed verse-prose stanzas marrying the narrative apotheosis of microfiction to the fatigued hope of a Shakespearean monologue:

I found a married priest in the snow

And not knowing what it was or why it was there, I ate a tart and gutted it

as if a LieutenantTo me, up to my polished gun holsters in bladder, the brandy was a surprise

I drank it in like the cunning wink of an exploding butterfly

on the lip

of a teacup while God upstairs puts a bag over His head

& gasses the house& says, “Well if I hated you I wouldn’t want my child to be like you, it makes no sense.”

Enter a shaken rooster of sin.

Fishkind’s Unretraction

It is a beautiful Saturday. Granted, it could be a little warmer, but I can’t really complain. I mean, I can complain, and I will, but that’s my prerogative, n’est-ce pas? I feel like shit. Am I allowed to feel like shit? I don’t feel like shit anymore. I can deduce that this shit-feeling came from my use of French, meant to be a quip. I can’t do that without apology. Consider this my retraction. I must retract a lot of things if I’m ever going to get back to baseline. I don’t know what that means.

I was awoken by my girlfriend’s cell phone at 5am, buzzing in the first email of the rest of her life. Her mother nervous about her brother getting stitches in a racquetball accident around 11pm last night. My girlfriend proceeded to text her brother, who also, inexplicably, was up and aware of this email, a chain of events stemming from his own personal world of hurt, literally, as he claims to have been hit by a racquet at such speed and flection as to have caused serious damage to his… skin? I don’t know why people get stitches. What I want to know is at what level of intensity of a wound does one leave the Band-Aids and peroxide at the wayside and shuffle down to the hospital on a Friday night. Maybe I’ve needed stitches in the past, maybe I haven’t. There’s a story my mother used to tell about my slicing my hand on some glass as a baby and getting “butterfly stitches.” And to me, that sounds worse than real stitches—perhaps implemented only to doctor the lacerations inflicted by a butterfly knife.

Awoken again, about 45 minutes later, her mother was calling, asking about details of the injury. My girlfriend says on the phone she has been asleep, a questionable remark, but what do I know being subject to that very plea. Her mother spoke softly about something I had lost, drifting away again into submission. The phone was placed again on the beside table, to go off again in a few hours.

Vidja Games and Mystery

Narrative is rarely any fun without mystery. You can get mystery in a lot of ways. In a creative writing class my senior year at Butler, my teacher Susan Neville passed a story around the room. I don’t remember what the story was. I think it was about two people in a car. I think they were young people. Susan pointed out that though the characters were taking turns speaking, neither one was responding to what the other person had to say. She said that if you listened to the way people really speak to each other, this turned out to be mostly true. We don’t listen: we wait for our turn to speak. What she didn’t point out was that this stood in stark contrast to the way college students tend to write, wherein a pair of extremely attentive conversationalists trade ideas and information in the collaborative pursuit of synthesis, consensus, etc. What she also didn’t point out was the way that this corrodes the mystery of the story: when two characters with ostensibly different interests agree completely on the direction of a conversation (or even on the terms of their own disagreement), the writer’s intent becomes glaringly obvious. So there is one way of creating mystery. Make your characters talk past each other.

Another way is to present an image so breathtaking, so rich with implications, and yet so beyond our grasp, that mystery can’t help but form. Another way is to create a character who makes interesting decisions that make us wonder why they made the decisions. Another way is to make thoughtful, sublime choices in language. Another way is to make thoughtless, sublime choices in language. And so on. Another way, but often a rather blunt instrument, is simply to withhold information. If your reader doesn’t know what’s going on, who’s doing it, or why, that counts as mystery, right? Well, sure. But maybe not the good kind.

The old Nintendo games tended to be naturally mysterious. There were many reasons for this. One is the graphical limitation of the system. NES games could only display a small number of colors with limited animation. It didn’t have a lot of pixels to work with, either — it was a very low-res system. This made the system’s representations abstracted, and, as such, a little mysterious. Sometimes (often) you literally couldn’t tell what you were looking at. READ MORE >

The 3rd Man by Graham Greene

The ocean is full of flowers that betray most readers. Or Graham Greene’s adulterations of poetic form in The Third Man are particularly well suited to his subject—racketeering. As we all know, on March 13, 1938, Germany took over Austria (termed the Anschluss)–a contingency specifically disallowed in the Versailles Treaty. Then we all took Austria back, but then it gets messy. This book is a tale of a “secret agency” (in the words of Sun Tzu) told through dialogue, exposition, tunnel chases, elegiac couplets, literary quotations, assassinations, and letters. Greene continues to be, as one critic has put it, “compulsively readable,” especially in his characterization of his villain, a charismatic but chronically unfaithful racketeer who publishes his friend’s writing as his own (westerns), and who is capable of saying “…I never lied to myself.” For example, the author spent nearly five million pounds, and employed over 150 researchers, in his mission to destroy martini lunches inside and outside the country (concerning events that happened over 60 years ago!). When needs arose our author may have used words that lied. Nonetheless, the hatted fellow cannot resist the money (this book was meant to be a screenplay), and his complicity is evident in the desperate acerbity of their dialogue (whispered). At one point, spy # 7 unleashes a terrific string of epithets: “lazy… plotter…sewage sucker…acronym…shootout child…liar…destroyer sadist fake.” Our hero Bond counters:

If you wish not to go on with this I’ll shoot.

Don’t shoot.

I’ve shot everything before.

What’s wrong with us.

Fog of war.

Why are we at war.

Because I don’t want to give up my penicillin.

Your dreams are a mess.

They are my masterpiece.

What specter haunts the sentence we’ve created?

Consider this moment in Kate Zambreno’s Green Girl, “For now, Ruth submits to nothingness. My Sleeping Beauty. She lies in bed still and flat, frozen before an unopened day.”

Combine it with that moment when we first meet the sleeping heroine Robin Vote in Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, “The perfume her body exhaled was of the quality of that earth-flesh, fungi, which smells of captured dampness and yet is so dry, overcast with the odor of oil of amber, which is an inner malady of the sea, making her seem as if she had invaded a sleep incautious and entire.”

Recall the moment of ghostly incantation manifested briefly in Hitchcock’s Vertigo: