Shop of work, or something like that

So, I’m teaching a grad-level fiction workshop for the first time next fall. I’m excited and nervous. It feels like a big deal. In my pedagogical statements, I write about how many fiction students don’t know how to read. That is, they read like they’re lit majors: they read for analysis and to say something clever about the text. (I was no exception before and during my MFA.)

BUT, but, writers read in a fundamentally different way. We read with our own writing in mind: what works, what doesn’t, what should we take from this writer, what does this writer do that we also do that fails, etc.

My undergrad fiction workshops are always very reading heavy. We read something like 8-10 books. Every book comes with some kind of “craft” lesson. I attempt to teach students how to read as a writer. Mostly, it works.

Yet even the most explicitly political acts of data gathering and collecting, like WikiLeaks, can succumb to a contemporary ideology of the self-sufficiency of information.

n+1 on information and art, then information and anger.

persnickety 11 sleep chucks

8. Slate says DFW would not have sent Pale King to a publisher. Awkward analogy alert:

9. Now that Amanda Hocking has sold out to become a go-go-gillionairre, Forbes weighs in.

Nine. The new JMWW is out.

10. Kevin Brockmeier interview.

I broach my sentences one tiny piece at a time. That’s always how it is for me — slow and considered. I’ll work and work at one little cluster of words. Then, when its rhythms are in place, I’ll move on.

11. John Gardner Fiction Contest ends in 9 days.

12. Ever watched video of your own self reading? How did that go?

Another Kind of Reading List

I always enjoy the reading lists posted here because I like to see what other people read but I rarely see a lot of the books I like to read. Half the time I haven’t heard of most of the books people are talking about. I am finally done unpacking my new apartment, seven months after the move, and I looked at my bookshelves and thought I would make a list of some of my favorite books, the ones I like to read over and over, the ones I read to relax and think and day dream. Some are “literary,” and some are “mass market,” but I don’t really think about books in those terms. I like good stories and these books all tell damn good stories. What are some of the books you love but rarely find on other people’s reading lists?

Drop it like it’s shottttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttt

People like to be entertained. They like to have something happen in front of them that makes them feel like they were there, saw something, can remember it thereafter. It’s a function of the fact that most of the time spent on the air occurs without definitive sequence or direction, at least not one that appears until the thing is over. This appearance of the sequence after the sequence has been completed is true of human lives, regardless of how directionless they may seem while they are going on, but it is also true of something like a table: a thing that does not move, exerts no proper influence. The story of any table, in its not moving, likely has more motion to it than a lot of things that traditionally exert arcs, such as a sitcom or a ballgame.

It is impossible for nothing to happen, really. The sentence “Orb fell through water.” exerts no definitive narrative product, but does show motion, and contains numerous hidden elements, i.e.: what is the orb? why did it fall? Many would expect then the orb to have a reason for falling, a product of its hitting the water, a cause and effect. But what if the orb is never mentioned again? Does this mean nothing happened? Could the appearance of the orb and subsequent lack of resolution thereby inscribe in the motion of whatever came after it, say “Days slurred numbers in a holy walk.” Is the orb in the days, slurring the numbers; why? Does the orb’s minor appearance lose its motion in not returning, the way a dog might pass your window? Obviously I think no, and some would argue that even if it doesn’t lose its motion fully it could have more presence by returning, but which is more masturbatory? Masturbation, often an ideological anathema to narrative wanting, seems defined by its repetition, by its return again and again to a familiar stroke, with a final climax that has no question. Sex, the stuff of most here’s-how-we-keep-you-interested,-by-having-all-the-characters-fuck-all-the-other-characters-and-or-die-one-by-one-style media, holds the relic of passing time, in the name of pleasure, such that at the end of it there is a thing on the floor and a happy body and a readiness to go to sleep.

I won’t say anything directly about America here, about how we are encouraged to go to sleep, because one of the functions of America is to make that argument sound like a supposed stroke in the supposed massive aesthetic jack off of “resolutionless art” that is actually perpetrated in the meat and bones of everything that has put us politically and culturally, on a majority scale, in the joke box of history.

At the Awl, a comprehensive post re: David Foster Wallace’s private self help library.

Did you buy How They Were Found by Matt Bell? He wants to give you a free ebook. Details on his blog.

Using Biographies

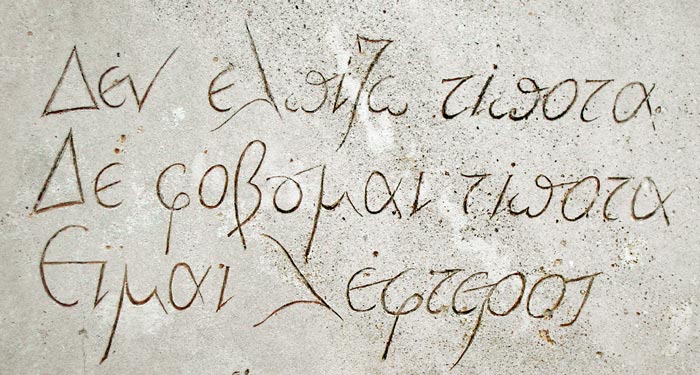

In Peter Bien’s introduction to his biography of Nikos Kazantzakis — Kazantzakis: Politics of the Spirit, Volume 1 — he quotes (apologies: this gets meta pretty fast) Stanley Hoffmann’s review of Annie Cohen-Solal’s Sartre: A Life, in which Hoffman says there are at least four ways to write biographies:

“especially those of writers as monstrously prolific as Sartre. One way is to try to deal both with the events in their private and public lives and with their writings. In the case of Sartre, this would require several volumes and an author who would feel competent to handle philosophy, epistemology, novels, plays, screenplays, politics, literary and art criticism and psychoanalysis . . .”

“Another possibility . . . is to try to find in the works the expression . . . of the writer’s personal traumas and conflicts.” A third possibility is to discuss the works at least briefly and to show “their connection with the author’s and the general public’s concerns of the moment, without providing an extensive analysis of the content or indulging in psychological reductionism.” Lastly, one can leave the work aside and concentrate on the life. “It is, of course, a debatable choice. What is Sartre without his books?” READ MORE >

The Poetical Taxon: A Questionnaire

My friend Joseph P. Wood wrote an interesting article over at Open Letters Monthly titled, “Taxonomy and Grace.” I think his basic thesis is encapsulated in these lines:

“While creative writing in American literature has always had camps, movements (and the prerequisite back-biting and bickering), I believe our current poetic climate is so conflicted and contentious that we have done away with talking about poems on their own organic terms. Let it be clear: I am not arguing for a return to New Criticism nor do I believe in the overtly easy-blame game of it’s the fault of those fucking universities. We live in the 21st century. What’s the point of asking to return to “the good old days” when those days would have excluded the likes of me — a working class, oddly educated, and peculiarly read writer with gaping holes in my canonical knowledge? I’m suggesting that while it is important to attend to our own academic reputations and political and aesthetic convictions, it is more important that we honor the imagination by not solely treating the poem against a singular interpretive mechanism.”

It might initially seem as though Joseph is arguing against the artist pigeonholing herself, right, by ascribing to one philosophical or theoretical stance, and this would be true, but I think he’s also genuinely concerned with the way we read and discuss poetry, the way we disseminate poetry. Has poetry become such an in-club that we can’t love a poem without ascribing it to a school or a movement? Do we have to know a shit-ton about Wittgenstein in order to speak intelligently about a poem? And as for the artist, is joining the club actually the job, or the business, of a poet (insert artist, writer, whatever besides critic)? Shouldn’t we simply write our way into the world? Are we in an age that forces us to straddle the fence between idea-schools and self-expression? What about the movements that aggregate what their members believe and create manifestos? I mean, where’s threshold beyond which the artist is in danger of losing her essential selfhood?

Read the article. Take issue. Praise its inherent belief in beauty and grace.