MASSIVE PEOPLE(5): Interviewers Around The Web

It’s been really busy around here. I mean, not around HTMLGIANT, but around our lives that are not related to HTMLGIANT: some of us were eating too much food and giving thanks, others were editing forthcoming books, others were grading student papers, and others were researching remote control helicopters. As a result, we don’t have a specific interview ready today for our series on MASSIVE PEOPLE.

Also, we are bad at checking our email. Things are a little disorganized at the moment (except for Secret Santa, which is really really organized – I’m serious).

Apologies.

What we do have, though, is a small festival of links to other interviewers around the web, those who are doing the work we failed to do for today. Please have a look at their stuff, and please add more links in the comments section if we haven’t mentioned it here. If you are working on a project like this, comment on it too.

- Kelly Spitzer’s Writers in Profile project

- Keith Montesano’s First Book Interviews

- Interviews featured at Bookslut

- And don’t forget the Indie Heartthrob Interview Series

- Interviews at Identity Theory

- Tao Lin’s ‘I Organized My Interviews Into One Post’ Post

- The Paris Review Interview Archive

- Interviews at Ron Hogan’s Beatrice

- Reader Meet Author at Orange Alert

- Author Interviews at Powell’s Books

- Interviews at 3:AM

- The fascinating Anorexic Chlorine Sex Toy Museum of Sean Kilpatrick

- Interviews at The Quarterly Conversation

- Interviews every month at Hobart

- Thunk: Interviews conducted by Ryan Manning

- NOÖ Loves Everyone

That’s all I can think of so far – should be enough to satisfy people looking around for an interview at HTMLGIANT. We’ll get on things and get MASSIVE back soon.

YOU MUST CONTINUE AT ALL COSTS: talking with Kevin Killian about his TWEAKY VILLAGE

YOU MUST CONTINUE AT ALL COSTS

Kevin Killian is a prolific novelist, poet, playwright, photographer, and Amazon-reviewer known as one of the original New Narrative writers. He’s also the author of the new poetry collection TWEAKY VILLAGE from WONDER, 2014. It’s a wild and ranging collection of poems/narratives that deal with the author’s response to free-market capitalism, the constraints of the English language, the repetitious nature of porn, and much more.

I first met Kevin whilst TAing for Dodie Bellamy’s infamous “Writing on the Body” class at San Francisco State University. Kevin Killian taught (and still does) at California College of the Arts. One day Dodie was absent and her partner, Kevin, arrived as the substitute teacher. (What a pleasant surprise!) We performed one of his plays featuring Kylie Minogue and a host of 90’s celebs, unpacked some abject bodily poems, and left with our minds forever altered. I remember Kevin engaging a student who had very conservative/fundamentalist views about sex and drugs. Kevin kindly and patiently explained that sometimes you need those kind of experiences to figure out what kind of life you want to have. Here Kevin discusses making up for lost time, neoliberalism, genre collapse, loving Arthur Russell, San Francisco’s shifting economic landscape, Santa Claus as Bill Clinton, his photo project “Tagged,” and on and on and onward.

***

Matt L. Rohrer: Hi Kevin! Thanks for doing this interview! I LOVE TWEAKY VILLAGE Could you tell a bit of the story behind this book? What was going on in San Francisco, in your life, in the world that spawned these poems?

Kevin Killian: Thank you Matt. I suppose it is a book of defeat really. Just as while writing ARGENTO SERIES I came to realize how little I had done to stop the march of AIDS, TWEAKY VILLAGE is me wrestling with how little I did to combat neoliberalism, which manifests itself visually every time I walk out my door and see the new, hyperwired global capital that is San Francisco today. Another thing that happened is that I began teaching and thus mixing with younger people and the contradictions of their beauty (or youth, which is the same thing), and the shrinking possibilities our world, our country holds out to them makes me feel implicated in the very system I detest.

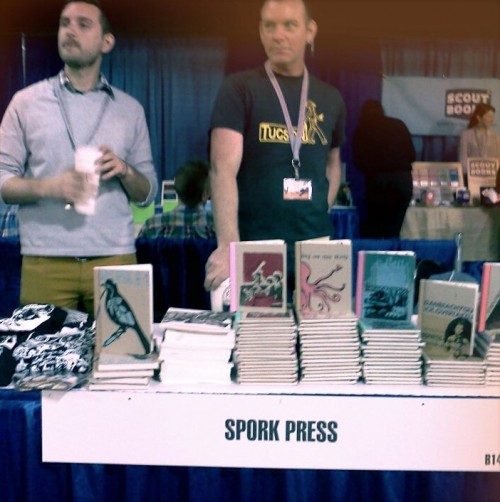

“WE DO WHAT WE WANT” – A Conversation with Spork Press

The Southeast Review will publish a review-essay I wrote looking at recent books by Carrie Lorig, Ariana Reines & Carina Finn. After I finished the review, however, I realized I was at least equally interested in the aesthetics & mechanisms of the publishers behind these books, as I was in the content. As publisher of H_NGM_N, I’m often making decisions & choices, trying to forge ahead, trying not to fall behind. And while I may know why I do what I do, it occurred to me that I know very little about why other people do what they do. So, I reached out to each of the publishers with a very targeted back-&-forth interview exchange in mind, a few quick questions to get behind the scenes a bit which I hoped would also help inform my reading of the works they produced.

In the following interview (conducted sporadically from early July through early September, 2013), I talk with the shadowy secret society known as Spork, publishers of Thursday by Ariana Reines. What started as an email exchange jumped almost immediately to a Google Doc, allowing all of the various tines of the Spork to check in, to comment, to correct, to dissemble.

25 Points: A High Wind in Jamaica

A High Wind in Jamaica

A High Wind in Jamaica

by Richard Hughes

NYRB Classics, 1999

279 pages / $14.00 buy from NYRB or Amazon

1. On the surface, Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica is a dot-to-dot adventure tale. After a hurricane hits an English settlement in Jamaica, two families decide to send their children back to England. Early on in the voyage the children are taken aboard a pirate ship whereupon they visit exotic ports and busy themselves with imaginary games. They are eventually returned home, and the pirates’ subsequent arrest, trial, and execution rounds out the proceedings. Of course, that last part seems a little extreme and out of place, and that’s really the book’s program, because simmering just below this surface is the constant threat of rape and murder.

2. In the spirit of Calvino’s later lecture on lightness versus weight, the narrative manages to float just above the threat of violence. You get the feeling after a while that Hughes is totally aware that you’re aware of the divide between high adventure and childhood trauma, and so he starts to fuck with your sense that awful things need to happen.

3. And, of course, awful things do happen—often and with startling frankness—but they are always quickly buried under the book’s relentless trend towards lightness.

4. The earliest memory I have is of staring up at the bottom of a kitchen table. I don’t know where I was or what I was doing, but I remember looking at a pattern in the wood and then turning toward a doorway. That’s it. I know I’ve told the memory differently over the years, adding in details about toys or sounds or maybe a smell wafting in, but the truth is that I just have this one scant moving image. I don’t think it’s a lie to embellish something so bland and colorless in texture, and at certain points I might have really believed in the additions.

5. Before I reread the novel to work on this review, I kept thinking it opened with a bigger feint at being a lighthearted adventure, but this is totally wrong. By the end of the first chapter’s scene-setting, two colonial ladies starve to death (or are fed ground-up glass by their servants, who knows!), a black servant drowns in a bathing pool, and countless rats and bats are dispatched by the family’s cat. All the while, we’re reminded that this is “a kind of paradise for English children to come to.” Right.

6. I usually skip introductions, but when I talk about AHWiJ, I almost always fall back on Francine Prose’s brief intro for the NYRB edition: “First the vague premonitory chill—familiar, seductive, unwelcome—then the syrupy aura coating the visible world, through which its colors and edges appear ever more lurid and sharp… The experience of reading Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica…evokes the somatic sensations of falling ill, as a child.” Sign me up.

7. Another big theme of the book’s opening is the whole colonial question, which is vital and pressing and could probably be handled with greater finesse than I can muster here. Suffice it to say that the first sentence presents ruined slave quarters, sugar-grinding houses, and mansions, all “fruits of Emancipation in the West Indies.” Considering the adventure-story-through-a-fun-house-mirror about to come, it’s hard not to think that this kind of stage-setting is about just rewards, that the English family deserves everything that’s about to come.

8. A brief digression cum recipe: AHWiJ allegedly contains the first mention of a drink called the Hangman’s Blood—a mixture of rum, gin, brandy, and porter—“innocent (merely beery) as it looks, refreshing as it tastes, it has the property of increasing rather than allaying thirst, and so once it has made a breach, soon demolishes the whole fort.” Clearly the kind of mix that leads to public exposure and pissing blood and, of course, piracy.

9. Is there actually such a thing as an anti-adventure novel? (I’d imagine something like Coetzee’s Foe might come close, although its meta-narrative seems more about deconstructing the adventure genre than teasing out its hidden desires.) And furthermore, if there were such an anti-genre, would it stand in opposition to all of the finicky colonial and gender and race problems inherent in Defoe and Dumas and Stevenson? While AHWiJ is never really a wholehearted rejection of the adventure novel’s Victorian and Enlightenment-era point of view, the ways in which it represses and then inverts these views are extremely sneaky and, by the book’s end, terrifying.

10. The narrative portrays the adult world as a haze of concealed motives and consequences. A pirate’s drunken leer and a parent’s concern over a coming hurricane are met with the same curious misapprehension: that something vital or alarming is just beyond one’s young recognition. But while Hughes draws a kind of tight circular POV around the children, he also lets the reader step out into the larger circle of this adult world, and somewhere between the larger circle and the nested one is a place where motives and the threat of their attendant consequences exist. READ MORE >

November 12th, 2013 / 2:14 pm

An Unconstrained Review of Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke

Ferdydurke

Ferdydurke

by Witold Gombrowicz

Yale University Press; First Edition edition, August 2000

(First published 1937)

320 pages / $8 – 25 Buy from Amazon

Talking past us, talking at us, at the open, the grand begin, from the onset another one of those sharp-edged misanthropic types, ever painful, absurd, so put-upon, the youthful thumb-bite, Lucky Jim, careening off the edge of thought, Under the Volcano, failing to recognize the genius before them, as though that “one-by-one box of bone” were such a shame for strangers, never to really know us, “ordinary fucking people”, sez our protagonist, Joey. From that position of unsteadiness, the feared impossible: not only the absence of reward, its perfect vacuum, sez our Joey, reversed through time to grade school again so that he might try a little better, having done something bad, having made a mistake. Luckily, it can be reversed.

How can we reconcile this, this poetic sensibility, with such devastating crudeness? Where is the perfect delicacy we’d been taught to cherish, the winking allusion, where do we find the much-needed descriptions of flowers, fields, a fencepost outside Dublin, waves, the blooming of the sakura blossoms, the vividity of maggots teeming in some peasant’s loaf of bread? How will we know how to think of trees if our books don’t tell us? There isn’t even bread here, all the crying children are assholes, the adults hem and haw and reinforce the base. Desire is the catalyst to every reaction, desire, especially those forms which fraternize with grasping, pinching, plumping. He reaches out and takes, he hides, all parties are whisked around like the Country Doctor, excepting those strangers who don’t seem in on the joke . . . but that would mean that we were in on the joke. Were we in on the joke? Where one of our sallow-cheeked Anglophile businessmen might pretend not to be in the apartment while some financial superior is banging down the door for up to five pages at a time, our rollicking little twit plays a long con through the door for . . . well, time kaleidoscopes, but he knows that she knows, she know or does not know, she would never let on, he would never let on. You thought of sex, then? How pathetic. A flower in a shoe provokes a scent-conspiracy enacted by a schoolgirl, but class warfare becomes a bonk on the nose. Anyway, back to sex. I’m not being coy, it’s just that the hierarchy of things is all messed up by Witty, and in the process he’s somehow managed to sneak a guffaw through the keyhole of a sneer. What is any one thing worth to another? I suppose it is true that I don’t know. The only difference between our world and his is that ours is occasionally illogical.

There is some other world out there where certain figures didn’t suffer the storm: Gombrowicz, Babel, Schulz, Brod. Kafka does too, the lucky devil. A whole separate slew of old white men, if a little more sickly than those we wound up choosing for the canon. Perhaps, in this other world, their full lives came at the expense of the popularity of a few of our dour old lepidopterists, those white-haired academicians who made ‘thrilling sentences’ and taught generations of young creative writing students the value of having that same sallow-cheeked businessman’s hands shake while he’s doing the dishes, just a few sentences before the end of the story. Couldn’t we afford to lose some of those endlessly relatable repressed suburbanites? Is it very hard to imagine a world where our writers reminded us, a little more angrily and a little more often, how near we are to nonsense? How funny that is, how sad it is? How horrifying the vacuum, how easy to gibber into it until it at least looks full? Wherefore the men for whom we golf-clapped, endlessly pleasing one another beneath the table?

It is very considerate of us to have excused ourselves for the inconvenience we posed, which did, after all, allow us plenty of time to swap spit-bubbles from Eliot, Pliny, Byron, Mistah Kurtz, to forget about Odessa in favor of some finely hyphenated adjective from the Odyssey, appended like a broach to the neck of a sentence. Still, what is it that drove Gombrowicz to stay in Argentina, what is it that drove an Argentine at the ‘opposite pole’ from the Pole to ask, “Who shall tell me, Israel, if you are found in the lost labyrinth of my blood?” Are we assuming that a people’s ability to save their own work from the fire exonerates us from the time we spent watching from across the street, if not working the bellows, if not ourselves the fire?

October 4th, 2013 / 11:00 am

The 50 Best Movies on Netflix Instant (My Version)

After coming across Josh Jackson’s recent list over at Paste Magazine, I thought: it’s a fine list, but my version would be considerably different. So, since I really really like compiling things, I decided to give it a go.

A few constraints/parameters:

(i) Despite the title, my list doesn’t pretend to be a “best of” list. It’s just a list of my favorites.

(ii) I didn’t repeat any of Jackson’s selections, even though he chose a few I might’ve included, like Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Delicatessen and Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich.

(iii) I only used one film per director, even in instances when I could’ve easily done multiple (Catherine Breillat, Wong Kar-wai, Buster Keaton, and Jean-Luc Godard come to mind).

(iv) Omissions abound, obviously. No room for Olivier Assayas’s Boarding Gate, Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, or Stephan Elliott’s Eye of the Beholder, to name but three of the missing I’d have liked to include. Then again, I enjoy the incompleteness of lists like these, that they can never truly be comprehensive is part of the fun I derive from composing them. Always, there will be a mistake. Always, they will be lacking. What a truly wonderful revelation!

(v) I started off intending to emulating Jackson’s numbering system, counting down from #50 to #1, but then I decided against it because it only reinforces the “best of” model by saying #1 is the best of the best and #50 is the least best of the best, and so on. Instead, you can just think about the fifty films listed below as one big assemblage of moving, striking, compelling, and provocative artworks I consider kick-ass and well worth your time.

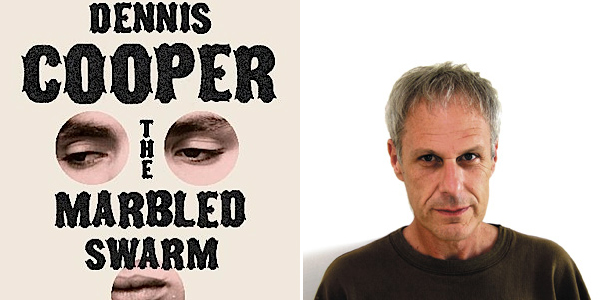

My fear arouses me: an interview with Dennis Cooper

The odds are decent that you know Dennis Cooper better than I do. After hearing about his work for years and constantly promising myself that I would try a little someday, I found myself graduated from the MFA program with time to read books of my own choosing again, and so I finally started reading his novels, and I haven’t stopped in the few months since. You’ve already read in this space about his latest book, The Marbled Swarm, a ludicrously powerful book that you really need. After reading The Marbled Swarm I had to send him some painfully earnest fan mail, and he received this note with a grace and generosity that will surprise no one who has read his blog. I asked if I could interview him. He said yes. His answers are more than worth your time; the book demands it.

So I had a really frustrating experience buying The Marbled Swarm at a local independent bookstore. I saw that they had two copies of Blake Butler’s There Is No Year shelved where you would expect, and I figured it would be easy from there because a) you share a press and b) “Butler” is alphabetically pretty close to “Cooper.” After a long search, I had to go ask one of the bookstore employees. She said that your book was supposed to be shelved in gay fiction, with a question mark at the end of her statement. (I was there with my wife; the employee seemed skeptical that I would want a book from the gay fiction section. I was sort of furious about that whole interaction.) And it was there! Do you like being shelved under the category of gay fiction? Do you think it’s been helpful for your work, commercially or otherwise?

I’m always surprised and disappointed when my books are cordoned off like that. I can’t speak to the reasons why that store in particular shelved The Marbled Swarm there, obviously, but, in general, I think it’s the result of a longstanding habit.

When I published my first couple of novels in the late 80s and early 90s, there was this vogue among critics and publishers regarding the notion of ‘gay literature’. I think that was the point where literary arbiters first cottoned onto the idea that there was a historical trajectory involving the work of authors who happened to be gay that had been largely unexplored and was ripe for a thinkfest. Also, there was apparently a decent sized gay male readership of fiction at that time. I remember people in the publishing industry saying that any gay-themed novel was pretty much guaranteed to sell around 5000 copies, so quite a number of writers who happened to be gay were being swept up by major publishers and given small advances based on the logic that the books would at least earn back if not even make everyone involved a bit of money. I’m not sure if that was actually true or not. READ MORE >

An Excerpt from Jarett Kobek’s ATTA

New from Semiotext(e) is Jarett Kobek’s ATTA, “a fictionalized psychedelic biography of Mohamed Atta that circles around a simple question: what if 9/11 was as much a matter of architectural criticism as religious terrorism?”

He prepares himself, watches television, hopes the box displays violence. But television is coy, intimates killings as abstractions. Beatings, certainly, beatings and brutality. But minimal death. Always the moment after. Police crash into a room, find a body, hunt the killer. But the actual kill? Off-screen. Or with guns. And what can he learn from guns?

Atta opens a video rental account, chooses movies that help with knowledge of death. He rejects Hollywood fantasies, imperialist propaganda efforts, prefers outlandish tales of monstrous abuse. The Horror section. Blood explodes in these films, bright red replica splashes on skin. READ MORE >

i’m a bullhole cliche / assshit: An Interview with Victoria Trott

When I started reading online literature, sometime in mid-2008, I discovered a short list of bloggers/writers (Tao Lin, Ellen Kennedy, Zachary German) with similar attitudes and approaches to literature. Later, when Muumuu House was established, I found, among them, a new name: Victoria Trott. I read her poems, her blog, and it was all very strange, funny, and poignant. On Halloween 2009, I met her at a late night get together in (where else) Williamsburg. She seemed quiet, estranged, grinning aimlessly. By then she’d sort of disappeared from the online scene, leaving behind only a few publications (not to mention an unreleased forthcoming issue of German’s now-discontinued litmag), an altered moniker, and a lot of questions. In late 2009, she created a hilarious, ingenious Twitter account, and in summer 2010, a wonderful new blog. Finally there was some clarity, openness, continuity, but still, I was curious. Last fall, I compiled a list of questions I had for (and regarding) Victoria in a Gmail draft. Then I emailed her some of those questions, commencing a slow correspondence, spanning three months. Here are the results:

David Fishkind: Hi Victoria, How are you?

Victoria Trott: Hey David, someone bought me breakfast today and I took half of a Ritalin, I feel pretty good. How are you?

How did you get involved with online literature? Or maybe, what is your time line of involvement?

Here’s a timeline of my involvement with online literature, which has the stuff about blog switching, I think

2007 – high school sophomore, read Hikikomori on Bear Parade. showed Tao Lin’s blog to my friend, she said “amoeba ass?” and laughed with a puzzled face.