FRESH OFF THE NEUE GALERIE: “THE ATTACK ON MODERN ART IN NAZI GERMANY, 1937”

Last Saturday I went all the way uptown to Neue Galerie to see the first American exhibition on the topic of “Degenerate Art,” which will be available through June 30, 2014. One of my favorite subjects during my ultra-brief academic career (aka “undergrad”) was the exploration of the factors that made the transition from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich possible. Above all other realms, that of culture was the one that appealed to me the most in my studying of how the German people were capable of gradually dehumanizing “non-Germans,” and to what extent this process was a political construct smoothly created by the Nazis. Reactively responding to German people’s despair and economic insecurity, Nazis built an ideology that made it possible for Germans to replace fear with hate for anything different. I am still fascinated by the institutional curating of art performed by the government, and what it translated to in political terms to have government authorities declare the validity of certain art, while condemning the existence of other art.

Maybe you should go see it if you feel like it and happen to be in New York, even if the security staff is unnecessarily rude. Especially if you are not familiar with what was presented as “Degenerate Art” and how it became a key tool in spreading Nazi propaganda.

My favorite thing about the Neue Galerie exhibit was the curatorial decision to dedicate the lower level part of the exhibition to a mourning ritual. Specifically, the curatorial team conveyed a sense of cultural loss by presenting empty frames in the place of artwork that was intentionally destroyed by Joseph Goebbels’ Commission for Disposal of Products of Degenerate Art, the government body responsible to preserve the German identity. An inventory which chronicles the status of what was labeled “Degenerate” can be also found downstairs, listing more than 16,000 artworks the Goebbel Commission would destroy, exchange or sell.

No Thanks: A Simple Wish for the Ends of Alt Lit

Last week I watched Nathan Staplegun eat salted peanuts on spreecast. What started off as Nathan eating salted peanuts soon turned into Nathan asking his roommates or friends (and thus turning the computer camera in their direction) what they were preparing in the kitchen, and quickly became a spreecast showing one of Nathan’s online friends playing guitar. On the surface, Nathan Staplegun eating salted peanuts on television (that’s what platforms such as spreecast are: do-it-yourself TV) would seem like a snooze, a no-brainer, an excuse to read more books. But, what Nathan did was really great. He put on TV a thing that he would have done anyway and by doing it on TV turned the act of eating salted peanuts into something else: an event, perhaps.

I love to tell the story of Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party. In 1978, Glenn O’Brien and friends (and his friends were people like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Amos Poe, Deborah Harry, Walter Steding, Chris Stein) got together and decided to take advantage of public access cable television in New York City. The format was simple: hang out with friends, get high (one episode had Fab Five Freddy in costume teaching viewers how to roll perfect joints), have your friends play music, and talk to people (viewers called in live while the show was on air and used their short time to make death threats and complain about how shitty the show was). By television’s standards, the TV Party shows were shitty, but they were fun to watch. And, in their own way, became increasingly popular (special guests included David Byrne, Klaus Nomi, and Mick Jones of The Clash) and influential (in one of his early top ten lists David Letterman cited TV Party as an influence). Art and everyday life will never be separate things; although, the art marketers sure seem to want us to believe that they are. Friends get together, record each other doing silly things, or someone we hardly know broadcasts himself washing dishes or whatever, and art’s possibility is renewed, if not, realized.

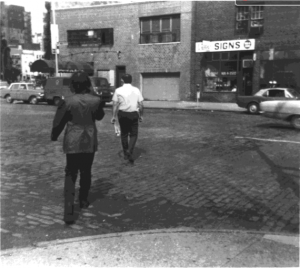

The word ‘creepy’ has not always had negative connotations. Vito Acconci follows people around New York City as part of his month-long performance ‘Following Piece’.

I have been kicking around the idea of starting a series of posts in which I cruise my facebook friends’ facebook photos and post the ones I like as part of ‘Creeper: Favorite Facebook Photos of My Facebook Friends’. The word ‘creep’ (and its variations) has not always had negative connotations. When Radiohead hit the pop charts in 1992 with their debut single “Creep” the song seemed like a strange, wonderful call to embrace the pathos of a loser, a lost subcultural weirdo whose dreams and desires are too much for himself and the world. Much like Beck’s “Loser” the song seemed to reinvigorate a long-standing yet dangerous tradition in the arts: the elevation of the low, the loser, the outsider, the emotional clown, to the status of cultural barometer, of artist. Long-standing because American cultural producers had carefully exploited this type for profit since the early days of white rock ‘n’ roll (Elvis Presley) and the first teen films (Rebel Without A Cause). Dangerous because sometimes people actually believed in these characterizations enough to begin to act like rebels, not satisfied with merely listening to them on the radio or watching them at the movies.

It’s not Dennis Cooper’s male escorts of the month. It’s The Bad News Bears (1976), who demonstrated that life sometimes artfully happens when a bunch of losers get together and push the game to its limits.

In 1969, Vito Acconci made art by simply following people around New York City. Acconci spotted someone on the street and followed them until they disappeared into a place he couldn’t, or didn’t, want to go. Acconci’s performance lasted almost a month. He’d get up, go outside, spot someone, and follow. Most spreecasts, for better or for worse, go on way too long. But, so does hanging out with one’s friends. At some point, you want to be by yourself or hang out with someone else. With the advent of the spreecast you can hang out with people you know or don’t know or want to know simply by joining in. It’s the logic of the club but not as restrictive. Of course, hanging out on spreecasts may never beat the intimacy of being in the same room with a friend or a loved one or turning it all off and reading a book. But I’ve known a lot of people who got all the companionship they needed by simply watching episodes of Breaking Bad or whatever–and apparently, according to some, you can be plugged in and still experience solitude.

This isn’t a plug for spreecast, who I could give two fucks about. It is a plug for a kind of art that denies the art market and realizes itself in everyday life. One doesn’t need an important architectural group, a big publisher, and a major museum to support an effort to follow and document people in your neighbor (although Acconci had all of those). One does need ideas. I was talking to Elizabeth Emily D’Agostino in her car about art. We were parked outside my apartment–a perfect venue to discuss anything. Our conversation shifted to cultural amnesia, an easy target. In our desperate efforts to predict the future I described for her a story written by Tao Lin and boldly proclaimed that this was Lin’s crowning moment and that history would look at this moment as an opportunity lost. The story is simple enough:

when i was five

i went fishing with my family

my dad caught a turtle

my mom caught a snapper

my brother caught a crab

i caught a whale

that night we ate crab

the next night we ate turtle

the next night we ate snapper

the next night we ate whale [. . .]

The last line of the story is repeated almost endlessly or as long as the writer/reader can endure it. Although, I have read a version of it where it ends rather abruptly. For a video account of its hilarity, you can listen to Tao read it here.

Why an opportunity lost? Because when an artist with the talent of Tao Lin comes along he seems to come with a two-pronged fork capable of reflecting the zeigeist back to us and/or breaking the hold the zeigeist has on our attitudes, desires, fashions, discourses, etc. In the post-Warholian world in which we live contemporary artists have made it clear that they are more interested in and perhaps more capable of showing us who they are (i.e. reflecting the ‘zeigeist’ back to us) than breaking the mirrors that bind us to a social-medial and political-economic worldview that reinforces the notion that ‘we’re fucked.’

May 1968, France. Today, the attitudes and aspirations of the ‘me generation’ of the 1970s have resurfaced in the attitudes and aspirations of millennial artists.

We are fucked. In Sheila Heti’s novel, How Should a Person Be?, someone comes up with an idea for an ugly painting competition. I say ‘someone’ because not even Sheila, our narrator, knows who came up with the idea. The idea of making the ugliest painting is more difficult than you’d think. Relationships are ended, lives are changed. During the height of the national crisis that was punk rock in England in the 1970s, a roadie for The Who dismissed the movement as a mere ‘revolt of the uglies.’ I mean, imagine calling a bunch of teenagers parading their misfortunes, economic hardships, childhood traumas, bad skin, social awkwardnesses, and fashion made of actual garbage found in the street as revolting or, worse, ugly? It is with these two sentiments in mind–a conceptual call to ugliness in the name of something else (Heti) and its celebration as an insult (punks)–that I invoke the writers and artists of the alt lit movement, a movement that has come to signify everything that’s right and wrong about everything that’s fast, cheap, and out-of-control in the arts today. Perhaps the time has come to break the mirrors that bind us to our own little personal victories (i.e. ‘I’m internet famous’) and begin the more fun and difficult work of smashing those fucking mirrors so that we–and the big, bad world–may see ourselves again, as something else, something more, something seemingly uglier and thus, perhaps, more beautiful. Of course, you could choose to ignore me (I’m used to it, really)–your career path probably profiting more from it–than listen to me whisper to you, from the salted peanut gallery.

@janeysmithkills

kottonkandyklouds.tumblr.com

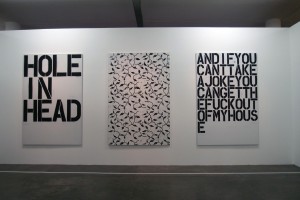

THE PERENNIAL AMBIGUITY OF CHRISTOPHER WOOL

I like Christopher Wool’s artwork. Wool became famous for his paintings of strong, provocative phrases in black letters, primarily ALL CAPS. Wool’s works are of an abstract nature, sometimes intricate in presenting an idea, other times arcanely elusive. In October’s Vogue Dodie Kazanjian scored a rare interview with the media-reclusive artist. The format and presentation of the arguments the writer provides to the text more closely resembles that of an essay, but many intriguing themes come up.

By introducing Willem de Kooning’s approach to artistic work–who worked “out of doubt”–as a starting point, the writer reveals the artistic intentions of Wool to be consistent in their omnipresent questioning and doubting. They are works defined by what Kazanjian calls a “perennial ambiguity.” This ambiguity may also be viewed as the proclamation of the honest confusion of an artist. Thus, the refusal of adopting an authoritative style should not be considered the result of limited intellectual rigor, but rather should be respected for its humility.

Discussing his artistic aspirations and how he managed to become a significant part of the modern art world, Wool asserts that his path was somewhat coincidental. “It just kind of happened,” he states. A key to his success was possibly that his early years in New York coincided with a legendary era of NY nightlife and culture: CBGB and Max’s Kansas City. The intersection of nightlife and the art-reality that was being created was evident in the 1980s, and shaped the public’s perception of artists’ role.

Upon revisiting his old work, the artist himself confesses: “They were offensive, funny, and indelible–you had to pay attention.” Consequently, it is not surprising that the critical response to his work varied. Some thought it populist in its negativity, while others observed in it a radical stance: a cacophonous harmony, or a refreshing pathos. What is predictable in his work is Wool’s lack of “conclusiveness” or the absence of artistic closure.

“I firmly believe it’s not the medium that’s important, it’s what you do with it,” the artist clarifies.

Stuff I Loved in 2011

That’s the feeling I look for, right? In whatever I’m eating, be it real food, or entertainment, art, people. The major event. A safe, manageable portion of the inner land or map blown away, torn out and away, dissolved or smoked. I only know a couple people who really seek that, or when they say they want that destruction it’s a good lie, and maybe they’ve said it enough so it’s shared and indistinguishable from truth. Regardless, it’s a common myth, a familiar dragon to chase, that of the Art That Changes For Good. I rarely recognize the mountain exploding in realtime, while reading something or watching a movie, it’s felt live that way maybe four times in my adultish life. Mostly it’s just feeling the echo of the boom a time later. Still, standing mountains aren’t terrible, and are often really nice. But sometimes you get lucky (pictured, pictured). Here’s what my year looked like:

“I’ve seen with growing disgust…”

“The Mona Lisa Curse,” by Robert Hughes. Part one of six.

UPDATE: “Apart from drugs, Art is the biggest unregulated market in the world.”

Something Film Understands but that Literature Doesn’t

I was talking with Jeremy M. Davies recently (actually, we were on our way to see Drive), and the topic of genre as art came up. Now, Jeremy and I are both huge into genre, in all media. We’re nuts over spy thrillers, sci-fi, and fantasy, for instance—not to mention Batman comics. (Only the good ones, though, natch.)

And of course lots of people in various lit scenes (all over) don’t think that genre fiction can be art. They’re really wedded to that “high art / low art” divide. (Or the “literary fiction / all else” divide, as it’s so commonly called.)

Me and J, we were saying how we don’t get it. How can someone read, for instance, Patricia Highsmith’s Ripliad and not recognize it as total artistic brilliance? Or Philip K. Dick’s VALIS, which is one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, hands down? And of course I’d argue that Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns is one of the finest things published in the 1980s, “despite its being” a comic book. (I didn’t spend all that time analyzing it at Big Other because I thought it was merely cute.)

Anyway, I came to a certain conclusion…

Favorite Passages from Deleuze & Guattari’s What Is Philosophy? (In Chronological Order)

To criticize is only to establish that a concept vanishes when it is thrust into a new milieu, losing some of its components, or acquiring others that transform it. But those who criticize without creating, those who are content to defend the vanished concept without being able to give it the forces it needs to return to life, are the plague of philosophy.

There is such force in those unhinged works of Hölderlin, Kleist, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Kafka, Michaux, Pessoa, Artaud, and many English and American novelists, from Melville to Lawrence or Miller, in which the reader discovers admiringly that they have written the novel of Spinozism. To be sure, they do not produce a syntheses of art and philosophy. They branch out and do not stop branching out. They are hybrid geniuses who neither erase nor cover over differences in kind, but, on the contrary, use all the resources of their “athleticism” to install themselves within this very difference, like acrobats torn apart in a perpetual show of strength.

If philosophy is paradoxical by nature, this is not because it sides with the least plausible opinion or because it maintains contradictory opinions but rather because it uses sentences of a standard language to express something that does not belong to the order of opinion or even of the proposition.

Philosophy thus lives in a permanent crisis. The plane takes effect through shocks, concepts proceed in bursts, and personae by spasms.

We do not lack communcation. On the contrary, we have too much of it. We lack creation. We lack resistance to the present. READ MORE >

Edge of Vision: An Exchange with John Duncan

John Duncan is an artist that has been working in the realm of art-as-experience since the mid-1970s when he lived in LA. His work has gone through many different forms and mediums as time has progressed, moving from direct actions at the start of his career to carefully articulated audio work as a primary outlet currently. Early on in his career Duncan found himself exiled from LA after performing a specifically transgressive performance piece, BLIND DATE. I find Duncan interesting due specifically to his insistence on art being affective, and how he has moved through and explored this idea throughout his career. The idea of affect is a powerful force no matter what medium it’s applied to, and Duncan is a master of transcendence, of reaching new feelings.

A couple weeks ago I emailed John Duncan with the request to ask him a few questions, and he was kind enough to comply and provide fantastic answers:

M. Kitchell:I have an interest in the consideration of “the artist” as a shaman, or the artistic practice as a shamanistic practice. What I specifically mean by this refers to “the belief that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds,” and the idea that “the shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community” (wikipedia). You have specifically expressed the idea that much of your praxis is geared towards learning, in a sense a self-education. It seems that an extension of this, in the presentation of the work itself, is the interest in a mode of communication, a way to share the experience and the knowledge learned. In some of your performance & installation work, it could be said that you are subjecting the audience to as much stress, or, perhaps, negativity, as you have submitted yourself to. There seems to be the intent of arriving at, say, a new consciousness, a discovery, an advancement. I think there’s generally an expectation of a distance between the audience and the work of art, but much of your work seems to deny that distance, it seems to specifically violate it. This denial of distance is not specifically something unique to your work, but much of your early work (SCARE, MOVE FORWARD, MAZE) seems to aggressively challenge this distance. Can you talk a little about this, how important the communication of an experience is to your work?

John Duncan:The essence, especially now, is not so much the communication of an experience as it is the experience itself. In all the works you mention, the point is to somehow get spectators to at least meet me halfway as participants. To make it clear that the extent the work reveals itself to a participant depends on whether or not the participant allows it to do so, on each person’s attitudes and character.

The difference between my earlier and more recent events is that in the past participants were usually trapped and forced to deal with a unique situation that they weren’t at all prepared for, which was essential to the event. Once trapped, it was up to the individual to interpret the situation as a threat or as a chance. Now, participants are free to leave at any time. They are given a condition to accept or not. For the person who does accept, decides to follow their curiosity, the work continues to open and develop. If the person refuses, everything stops there for them, the knowledge that they couldn’t let go is what they take home.

James Pate at Montevidayo says some really precise stuff about chaos and art, ending with this (YES): “With both–and with Grosz too, I would say– we’re left with an aesthetic that I like to think of as the abandoned house approach to art. You go in and wander around, but no one lives there anymore.”