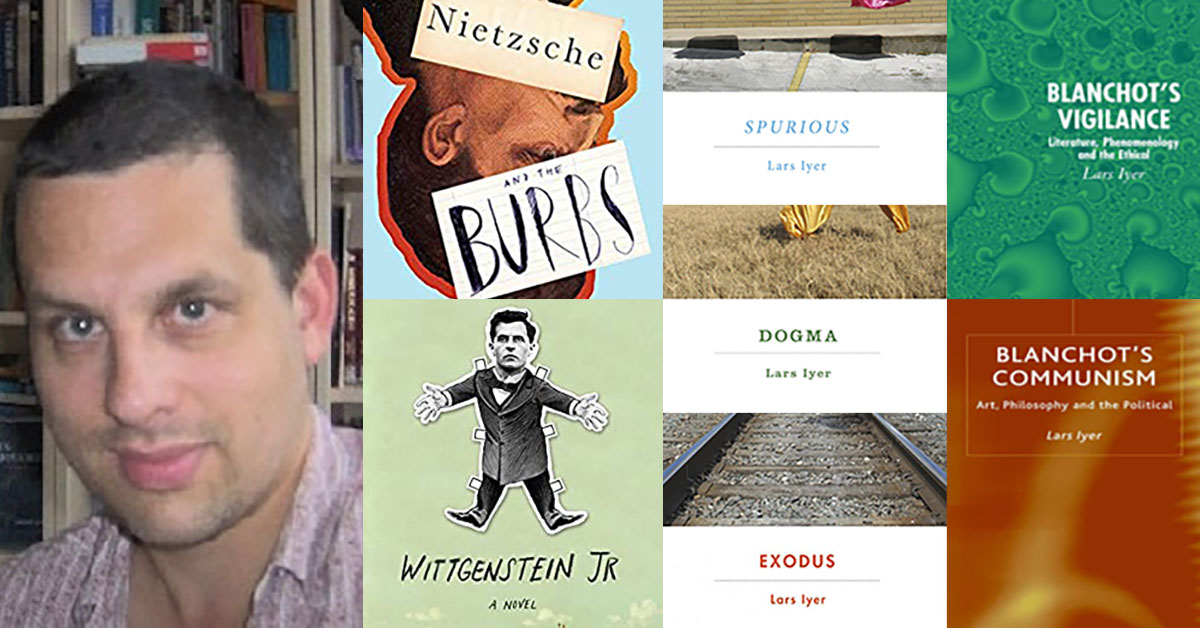

Lars Iyer emerged in the early 2000s as a leading scholar on the work of Maurice Blanchot, publishing Blanchot’s Communism (2004) and Blanchot’s Vigilance: Literature, Phenomenology and the Ethical (2005). In 2003, he began performing creative writing experiments at his blog, posting fragments of fictional narrative influenced by his work in philosophy. The result of these experiments was the Spurious Trilogy (Spurious, 2011; Dogma, 2012; and Exodus, 2013), a series of short, episodic, and brilliantly funny novels about two gin-loving UK philosophy professors, Lars and W., who await the apocalyptic event or messianic arrival that would mark the end of our end times.

Iyer’s new trilogy (Wittgenstein Jr, 2014; Nietzsche and the Burbs, 2019; and Simone Weil, in-progress) also depicts characters struggling to live and think during and beyond the end, and it continues his experimentation with combining fictional narrative and philosophical thought. In Wittgenstein Jr, a group of Cambridge philosophy students refer to their professor as Wittgenstein, having noted similarities between him and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. The philosophy students, like Lars and W., are looking for a leader, someone whose way of life might serve as a model for their own — they may have found it in this 21st-century Wittgenstein. In Nietzsche and the Burbs, the conceit is similar. A new student, formerly enrolled at a private high school in London, has transferred to a public school in the suburbs. The novel’s narrator, Chandra, along with her friends Paula, Merv, and Art, begin calling him Nietzsche. They’re drawn to this 21st-century teen Nietzsche’s unconventional answers to questions in class; to his aphoristic posts at his blog (“last-philosopher-dotcom”); and to the smile on his face as he listens to a teacher read from a novel about a Wittgenstein-like character building a cone for his sister in the middle of a forest.

The following interview consists of emails that Lars and I exchanged in October–November 2020.

Evan Lavender-Smith: I especially enjoyed a sequence of scenes near the beginning of Nietzsche and the Burbs. In the first scene, Chandra, Paula, Art, and Merv sit by a river and discuss their experience of life in the suburbs. They lament that their intelligence has been “crabbed … turned in on itself … squandered on movie trivia … on the ranking of favorite albums and films”; they say they’ve been “overstimulated … overprogrammed … grade-inflated … infotained”; they call themselves “the most useless generation that has ever lived … the most pampered … the most unchallenged … the most unhappy.” In the next scene, the friends have returned to school for free period:

It’s like Groundhog Day. We’re living the same day over and over again. We’re living the same free period over and over again until we learn some lesson.

What lesson? I wonder.

That life sucks, Art says.

We’ve learnt that, I say.

That nothing’s ever going to happen again, Paula says. That we’re marooned in the suburbs forever.

We’ve got farther to go, we agree. We must annihilate all hope. We must expect nothing—nothing.

Hope? What’s hope? I ask.

We must forget the very word, hope, we agree. The very memory of hope…

Bill Trim, sitting down with us.

You’ve found us at our lowest ebb, Bill, Paula says. We’re full of nihilism.

These adolescents are in a state of despair — but I’m still laughing here, as I am on nearly every page of the novel. In the historical Nietzsche’s writing, laughter serves as a figure for an “active” and “affirmative” nihilism: a courageous acceptance and affirmation of the loss of belief, followed by a creative redefinition and restoration of belief. In your manifesto (“Nude in Your Hot Tub, Facing the Abyss: A Literary Manifesto after the End of Literature and Manifestos”) you write, “It is an image of farcical life that shows its hand in that literature which comes after Literature,” and you refer to a “cleansing painful laughter that splits your sides and your heart.” I wonder if the laughter you describe in the manifesto is comparable to the historical Nietzsche’s laughter. Would this laughter — the laughter of active and affirmative nihilism — allow the adolescents of your novel to overcome their despair?

Lars Iyer: The adolescents of my novel live in a world that has no room for negativity. It’s totally managed, totally processed, totally realized, and all under the banner of happiness. Nothing actually happens — pseudo-event follows pseudo-event. There’s nothing new — the future is programmed, prescribed, totally modeled.

Everything other has been categorized and absorbed. Everything’s visible — in hi-res. In high-definition. In pure-self-evidence. There are no secrets left, no shadows. Everything’s taken straight. There’s no irony. The world is what it is and nothing more.

Instead of politics: quantified management. Instead of the ethics of self-cultivation: the entrepreneurial self. Rebellion is prepackaged, clichéd. Disobedience runs along obedient grooves. Education is indoctrination, little else.

This is the void of post-history, in which every attempt to bust out is neutralized in advance.

On wild, drunken, drugged-up nights, my characters wax apocalyptic — they want to negate this overlit, oversaturated, overdeveloped world in its entirety. Theirs is a total laughter, a laughter that finds everything ridiculous. It’s liberating — freeing. It loosens the hold of the present, of all worldly hopes. It accepts that nothing in the world is going to help us. It’s a laughter unto the death of this world, this system. Of the world’s self-inflicted death at the hands of climate catastrophe and financial collapse.

Such apocalyptic laughter laughs at itself, too. At its vanity, its hyperbole, its excess. It laughs at itself as all too human, all too finite …

Only faint echoes of such laughter remain afterwards. Sure, you can ascend to the plane of apocalyptic laughter on wild nights of drinking and drugging, but there’s always the descent, the morning after; there’s always ordinary life, which is, for my characters, privileged, middle-class suburban life, and dull, dull, dull. There’s just boredom, suburban ennui, and the vague nihilistic desire to say no to the world …

The historical Nietzsche hoped nihilism could be transformed — that it could become active and affirmative, not merely saying no to the world, but saying yes, thereby overcoming despair, at least for a time. We are to accept fate — everything that’s happened — as though we wanted it thus, as though we wouldn’t have wanted anything else. What a task!

My teens think this might be possible through music. Create the right kind of music, share it with others, and you can affirm the path that led to this act of creation. You can gather up all the contingencies of your life — that you happened to be born here, that you went to this school and hung out with these people — into a kind of necessity. The suburbs, and everything about your suburban life, can be affirmed as the condition of music-making. This would allow my characters to triumph over their hatred of the suburbs and thereby overcome nihilism.

But can you really affirm everything exactly as it is, without wishing it to be different — better? And if so, would you be obliged to include cruelty, bullying and all the humiliations of school life in your act of affirmation? Indeed, how inclusive would the affirmation have to be — would you have to affirm everything about your life; about the lives of those around to you; about your parents’ lives; and those of your next-door neighbors? Where would you stop? Would you have to include everyone and everything: the whole world; the whole universe, all of history?

(And why is affirmation the model, anyway? Isn’t it more appropriate to condemn parts of our lives? And wouldn’t it be better to simply escape the suburbs and find somewhere else to live — a queer bohemia, perhaps, as Paula suggests?)

You quote from my manifesto. “It is an image of farcical life that shows its hand in that literature which comes after Literature.” Such farcical life is what’s left on the eternal day after, the eternal hangover, when apocalyptic laughter has died away. And it’s marked by a bathetic writing, which, as Pieter Vermeulen has explained in his Contemporary Literature and the End of the Novel, is neither resigned to the soft triumphalism of our overmanaged world, nor able to rise to the tragic heights that, according to the historical Nietzsche, might allow us to transfigure it.

Lavender-Smith: Music’s potential to transfigure nihilism reminds me of another figure used by the historical Nietzsche: dance. The epigraph to Nietzsche and the Burbs (“You must have chaos in your heart to give birth to a dancing star,” from Thus Spoke Zarathustra), reappears later in the novel as the chorus for “Dancin’ Star,” a song composed by Merv. As in your previous novels, which also frequently reference music, there’s a trancelike quality to the prose. Repetition, ellipsis, consonance, and any number of other devices contribute to this—including a particular technique that involves rapid alternations between direct and indirect discourse, a conflation of Lars and W.’s voices that, to my ear, creates a continuously surprising prosody. I’ve just now closed my eyes, opened Spurious, and placed my finger on a paragraph. Here it is:

How’s it come to this? W. says. What wrong turn did he make? He was like Dante, he says, lost in a dark forest.—“And there you were,” he says, “the idiot in the forest.” I was always lost, wasn’t I? I didn’t even know I was lost, but I was lost. Or perhaps I was never lost. Perhaps I belonged in the forest, W. muses. Perhaps I am only that forest where W. is wandering, he says, he’s not sure.

Vermeulen, whom you mention, describes your technique as one of “never allowing the first-person narrator, Lars, to speak for himself; instead, Lars mainly renders W.’s verbal abuse of him, mostly in free indirect discourse (in which Lars is referred to as ‘I’), sometimes directly (in which he appears as ‘you’).” Like Vermeulen, I’m interested in the relation between the narratological and metafictional features of your writing (e.g. conflating the voices of two characters, one of whom shares your first name), but I’m more interested in the relation between the writing’s narratology and its music. As Vermeulen notes, your novels are often compared to those of Samuel Beckett and Thomas Bernhard. I wonder if this comparison follows, in part, from a shared appreciation of music’s value when it comes to conceiving and creating form and language in narrative writing. How do you imagine the relation between music and the form of your writing?

Iyer: I don’t believe in novels that don’t know how to dance!

Rhythm, in particular, is central to my work. There’s a spring to my prose. Clipped sentence fragments, all run together, with the use of italics for emphasis … Ellipses opening within sentences, trailing off at the end of them … Blanks between sections …

I’m always after a sense of flow. Émile Benveniste tells us that the Greek word rhuthmos did not originally mean a pulsed beat, a regularity imposed upon chaos. For pre-Socratics like Heraclitus, the word suggested something fluid or in motion — something flowing, improvised and changeable that swirls around regularity, opening it up (think of drummer Tony Williams in Miles Davis’s second great quintet).

Two millennia after Heraclitus, Nietzsche revives this sense of rhythm in his account of the Dionysian drive. In The Birth of Tragedy, this drive is linked to both death and chaos on the one hand, and eros and the affirmation of life on the other. It is both creative and destructive. The Apollonian drive, by contrast, is focused on the clarity of form, of beauty, throwing a veil over the Dionysian flux and constructing the necessary illusion that there are individuated entities that are part of an intelligible and stable world, rather than just dynamic processes of becoming.

Nietzsche makes use of the Apollonian and Dionysian forces in his discussion of rhythm. Rhythm as such is a breaking up of undifferentiated flux into regular intervals. The Apollonian places emphasis on the even division of rhythm, on a wave-like beat. The Dionysian is linked to the use of stress that allows rhythm to be felt much more viscerally — to become danceable, to approximate the ancient sense of rhythmic flow.

In my novel, I often work with stress, accentuating the rhythmic meter of my prose with punctuation and italics and deploying repetition at the level of the sentence, the phrase and the word. It’s my way of continuing the lyrical flow I find in the real Nietzsche’s prose. (I discuss the role of music for Nietzsche and in my novel in more detail here.)

I often seek a relentlessness — a fairground careening not dissimilar to The Fall’s 14-minute “And This Day” on Live in Reykjavik. But I want this relentlessness to be broken, too — to be undone by brief hiatuses. That’s the role of ellipses and interruptions between sections.

Here, I think of Miles Davis’s magnificently funky “Aghata,” on the album of the same name — rapturous, funky, but also smashed into periodic breaks, where we hear the held notes of an organ. The music seethes and boils propulsively — it’s a real bitches’ brew — but it opens periodically into sonic equivalents of vistas — into unbound flux, where relentlessness rests, and, for a few moments, you can close your eyes, before the funk starts up again …

You mention the epigraph to Nietzsche and the Burbs, which chimes with that of Wittgenstein Jr (“When you are philosophizing you have to descend into primeval chaos and feel at home there”). Both novels concern the necessity of engaging with chaos — a central theme of these novels and the one I’m working on now, Simone Weil. Order is security, structure, pattern — but it can become fixity. Chaos is freshness, novelty, but it can also upset, overflow … The question: how to balance the two in a living form — a “dancing star” (Nietzsche and the Burbs) or in a way of life (Wittgenstein Jr)? How can their dynamic enliven the world in which we live?

In my novel, Wittgenstein’s brother takes his life because he cannot embrace disorder. My Wittgenstein, with the help of his students, learns that the flux of becoming isn’t necessarily to be feared. Sure, he won’t be able to finish his Logik — his masterwork, which was supposed to answer the cosmic order. But that project, as he learns, was ill-conceived. He lets himself embrace friendship and love — and with them, the chance of imbalance, of chaos. Will he be spared the madness that enveloped his brother, or will he find a way to live with what he hitherto feared?

My Nietzsche also fears madness, which is a kind of chaos of the brain. His band seeks to unleash Dionysian forces in music, opening out the song-form. They admire Can’s Future Days — Damo Suzuki’s feather-light vocalizing; music as mist, as spray, as shimmering expansiveness. They’re lovers of Pauline Oliveros, who lets us hear deep trance, the aum of the universe.

Nietzsche’s bandmates seek to unbind traditional song structure, surrendering compositional control in a communal and improvisational music practice. But is such surrender too risky for Nietzsche, who might have preferred, like his historical role model, to master chaos through the rhythmic progress from dissonance to consonance — to the production of harmony? Wouldn’t he want to turn chaos into something beautiful and complete, seeking the Heraclitean unity-in-strife of a “dancing star”?

Lavender-Smith: We’re alternating between referring to “your” Nietzsche and the “historical” Nietzsche. Obviously, anachronism is present in both Wittgenstein Jr and Nietzsche and the Burbs: we read of 21st-century characters named Wittgenstein and Nietzsche who say and write/blog things similar to what the 20th-century Wittgenstein and the 19th-century Nietzsche said and wrote. But there’s something special about the anachronism: the novels recapitulate — and perhaps even enact — the contemporary experience of reading the historical Wittgenstein and the historical Nietzsche. Following the students in your novels as they attempt to come to grips with contemporary life under the influence of these philosophers’ thought isn’t far off from my own experience in reading philosophy. I’ve been reading Foucault on biopolitics in consequence of the current pandemic and US election; like your characters, I find myself looking to philosophical thought I admire with the hope of being led toward a more rigorous conception of how we live and think today, how we might better live and think tomorrow. I’d be interested to hear more about the thinking that went into your decision to “recast” these philosophers in today’s world. Why Nietzsche?

Iyer: Nietzsche never felt he was part of his time — he had been born too early. His philosophy, he believed, belonged to the future — to the “new philosophers” he evokes in Beyond Good and Evil; to the “future nobility” he mentions in The Gay Science.

The late Bernard Stiegler agrees: it’s only we, who live more than a hundred years after Nietzsche’s death, for whom his notion of nihilism becomes clear — who can really experience what the “death of God” means.

For Stiegler, ours is the period of the “apocalypse” of nihilism, in which it is unveiled in a commonly felt despair. This revelation is the result of a civilizational collapse in the sense of possibility — of the very basis of our projects, initiatives and motivation.

Until recently, according to Stiegler, this despair was concealed by a positivity and can-do-attitude that determined our sense of ourselves. “I can do it all” — this was the premise of the entrepreneurial self at the basis of our “achievement society,” as Byung-Chul Han calls it. But such positivity didn’t last; and the apocalypse of nihilism arrives:

When despair becomes the most common experience, the most widespread, it is no longer possible to ignore the specific questions raised by the death of God, the questions, dare I say, worthy of the death of God.

(“We Have to Become the Quasi-case of Nothing — of Nihil: An Interview with Bernard Stiegler”)

The characters of my novel know all about despair, which is why they are receptive to my Nietzsche’s proposed remedy. He exhorts his bandmates to drive their despair deeper, to really experience their unhappiness — as he puts it, to complete nihilism and, in so doing, overcome it. My Nietzsche tells them to say yes to suburban reality exactly as they find it, in all its dreariness. Even the cruelties of school life are to be embraced and affirmed. This is what inspires the attempt of my teens to achieve amor fati, embracing their suburban fate, through music.

But despite Stiegler’s claims about the relevance of some of Nietzsche’s analyses, there is also real anachronism in reincarnating him in the contemporary world. There’s little knowledge of, or interest in, figures like Nietzsche in the UK — perhaps it is the same in the USA. Philosophical thought of this kind, which is embedded in the spiritual life of the thinker (I’m thinking of Pierre Hadot’s analyses) is no longer part of our culture.

This is why I felt I had to present my Nietzsche in the burbs as a rather ghostly figure. My teen characters already feel themselves to be posthumous. Well, my Nietzsche’s even more dead, if that’s possible. He whispers, rather than sings. When he talks — he’s very reticent — it’s as if from a great distance. He hides himself away; he doesn’t make himself available for friendship. He does drink, but refuses drug-fueled Dionysianism of the others. He never seems really joyful …

Lavender-Smith: Before writing the Spurious trilogy and teaching creative writing, you studied and taught philosophy, wrote books on Blanchot and articles on a wide range of topics in philosophy. I’m wondering how you conceive of the difference between reading/writing philosophy and reading/writing fiction. I often think of the way Deleuze and Guattari’s distinguish philosophy and art — philosophy creates “concepts”; art creates “sensations” — and I find myself on the lookout for works of philosophy and art, especially fiction, that trouble this distinction. Do you find it worthwhile or possible to think in categorical terms about the nature of reading/writing fiction and the nature of reading/writing philosophy?

Iyer: Perhaps it’s a question of renegotiating the boundaries between the two — of reflecting on how fiction might be said to think philosophically, and indeed of the philosophical use of fiction.

In recent years, there has been talk of film being a mode of philosophizing, of thinking, for example, in Robert Sinnerbrink’s recent book on the film director Terrence Malick. This might seem an odd claim — after all, film is a visual narrative art, and doesn’t make arguments or draw conclusions, so it isn’t obviously philosophical according to our usual understanding of the word. But this assumes philosophy must refer to the standards of professional, academic thought — to the framing of arguments, analysis on concepts, articulation of objections, etc.

Sinnerbrink argues that philosophy should be understood more broadly than that — as a kind of ethical reflection, which might deepen our capacity for imaginative moral experience, even lead to moral transformation. Film — but we can extend Sinnerbrink’s point to encompass all the arts — contributes to human flourishing in this capacity to philosophize in this way.

But the arts, fiction included, are not only about expanding the horizons of ethical meaning and thought. Look what, for example, Beckett’s The Unnamable shows us about selfhood and language. What about the way Woolf helps us rethink time and perception?

You mention Deleuze and Guattari’s distinction between philosophy and art. I think of Laura Cull Ó Maoilearca’s suspicion that it remains too schematic since they do not allow artistic practices to constitute modes of research in their own right, and has constituted a network of artists and thinkers engaged in “performance philosophy.”

Lavender-Smith: You’ve reminded me of John Ó Maoilearca — Laura Cull Ó Maoilearca’s partner — specifically his writing on film and François Laruelle’s “non-philosophy.” Like you, I’m attracted to the possibility of dissolving boundaries between philosophy and fiction; I’m also attracted to Ó Maoilearca’s proposal, via Laruelle, that we rethink their very definitions. In Refractions of Reality: Philosophy and the Moving Image, Ó Maoilearca begins by sympathizing with Andrew Light’s admission in Reel Arguments that Light has sometimes “wished he was a filmmaker rather than a philosopher.” When I read your novels, I often think of film: your characters frequently reference film and your writing borrows conventions from screenwriting. Would you talk about the influence of film on your writing? I also think of Laurelle and non-philosophy when reading your novels, especially the Spurious trilogy. Has Laurelle been an influence?

Iyer: I’m in debt to John Ó Maoilearca’s work for bringing Laruelle’s difficult ideas to life with such clarity. I admit I’m only the barest beginner when it comes to Laruelle, so you’ll have to take what follows with a pinch of salt …

Looking through the Spurious trilogy just now, I couldn’t find the phrase “non-philosophy,” which I was sure I’d used … But I found a paragraph in a draft of Exodus, which I’d cut in the name of furthering the flow of my prose:

Why does he collaborate with me?, W. wonders. Why does he bother? He’s had to justify it so many times to his philosophical friends, W. says.—“Lars has developed his own legitimate madness,” he’s told them, paraphrasing Char’s poem. There’s a kind of greatness to my idiocy, he’s explained. Lars has discovered another kind of thinking, W.’s said. Non-thinking, that’s what W. calls it. Non-philosophy. But his friends never understand.

For W., Lars embodies a charismatic idiocy, a fascinating madness. Of course, W. spends most of his time in the novels berating Lars for his appetite and obesity (W. is said to eat, by comparison, very delicately), his love of squalor (W., by contrast, lives in a Georgian ship’s captain’s house), his apocalypticism (which altogether lacks W.’s supposedly counterbalancing messianism), his obsession with blogging (not real philosophical labor, apparently), his general hysteria (versus W.’s cool-headed sobriety), his penchant for Jandek and mass culture (instead of an exclusive diet of arthouse films and literature), his allegedly working class background (which W. supposedly shares, although he went to grammar school).

Yet W. is fascinated by Lars, too — in particular, by his “non-thinking,” which he links to his friend’s former unemployment and low-status warehouse work, to his experience of the everyday as “the infinite wearing away.” Lars’s greatness, for W., lies in his position as an outsider thinker, who, like Deleuze’s figure of the idiot, is capable of “counter-thoughts,” questioning abstract, rational truths and the power of established order.

Ó Maoilearca reminds us of Laruelle’s suspicion of this elevation of the idiot. Deleuze, according to Laruelle, retains the usual hierarchy, placing the philosopher higher than the “counter-thinker.” Sure, Deleuze might claim that the idiot is able to turn “the absurd into the highest power of thought,” but it still takes a philosopher to make this claim on the idiot’s behalf.

This confirms what, for Laruelle, is an authoritarianism built into philosophy itself. In truth, “the philosopher does not really want idiocy.” Deleuze would never let himself really think like an idiot or write a truly idiotic philosophy. As Ó Maoilearca explains, Laruelle looks instead for a “transcendental idiot” who is not merely a philosopher’s stooge.

Is the Lars of the novels such a “transcendental idiot”? W. associates him with the non-logos that exceeds the order and sense of the philosophical logos, disclosing it as merely a restricted economy within a larger chaotic field. Lars is an outsider thinker, perhaps even an antiphilosopher, and is therefore immune to the usual temptations of the academic: careerism, selling out, writing student-friendly textbooks, etc.

But perhaps we can understand W. to be assuming what, for Laruelle, is the typical position of the philosopher by trying to master Lars’s idiocy, seeking to translate Lars’s non-thought into philosophical thought, Lars’s non-logos into the philosophical logos. That’s the ambition of their Dogma movement.

Of course, to complicate matters, W. does this in a book written by Lars, and in a literary and not a philosophical work. In so doing, is Lars fighting back? Is this Lars’s literary attempt at mastery? Is Lars trying to translate philosophical thought into a literary non-thought?

W.’s dream in the trilogy to allow Lars’s non-thinking to infuse his own thought with new life, to let idiocy rejuvenate the old verities and to give non-philosophy its philosophical head. He dreams their movement, Dogma, will combine his philosophy with Lars’s non-philosophy and lead to an entirely new form of thinking.

But what of Lars’s dream, this blogger who has published literary books about his friend? What is the relationship of Lars’s novel Dogma, which narrates the rise and fall of this movement, to W.’s dreamed-of thought revolution? And where do I stand with respect to Dogma as the Lars who is its real author?

Is the Lars of the novel W.’s stooge? Or is W. Lars’s? Which one’s the idiot? And where do I stand — the “real” Lars? Is literary writing philosophy’s stooge in my work? Or is it the other way round? These questions are performed in the trilogy by means of literary writing and the philosophical (or non-philosophical) manner of thinking that belongs to it.

Questions for future exploration: what would non-literary writing look like, in Laruellean terms? What would the relationship be between such a writing and the post-literary writing I call for in my Manifesto? …

You ask me about film. Yes, film is indeed a constant concern of my characters, never more so than in the novel I’m currently writing. Simone Weil is based on the life of the philosopher, but set, like Nietzsche and the Burbs and Wittgenstein Jr, in the present. One character, Ismail (named after a character in Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander) is a would-be film-philosopher, a PhD student, intent on making a film that does what only film can do.

At first, Ismail tries to ape avant-gardism, to the derision of his friends. He moves on to remaking scenes from Tarkovsky and Malick films, pastiching the art-film and foregrounding its anachronism. Finally, under the influence of Jonas Mekas, he decides to work with fragments of everyday life instead — to film his friends larking about.

Ismail now embraces his own technical shortcomings, no longer worrying about over- and under-exposure, variable focus, etc. Like Mekas, he wants simply to present his viewers with one epiphany after another, with fragments of paradisiacal life. He’s making a non-film, perhaps …

As you mention, John Ó Maoilearca has said he’s sometimes wished he was a filmmaker rather than a philosopher. Back in the days before I wrote Spurious, or even started the blog on which it was based, I dreamed of becoming a literary writer. And now I am one … or am I? I’m reminded of the old story:

Once upon a time, Chuang Chou dreamed that he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting about enjoying himself. He didn’t know that he was Chou. Suddenly he awoke and was palpably Chou. He didn’t know whether he were Chou who had dreamed of being a butterfly, or a butterfly who was dreaming that he was Chou.

Maybe I’ll wake up one morning and find myself as the academic philosopher I used to be, dreaming of non-philosophy or non-literature or who knows what …

Lavender-Smith: Today is the eve of election day here in the U.S. I woke up this morning and found myself behaving in the manner of the MFA graduate student I used to be, cuddling an empty bottle of bourbon and Emil Cioran’s The Trouble with Being Born.

Lately I’ve found myself yearning for transformation on the order of transcendence. Characters in your novels yearn for transcendence, as well, and yet so many recent philosophers insist on immanence as a frame for transformation. Nietzsche and Deleuze address the problem of maintaining this immanent frame by offering new solutions: nihilism must be “overcome” (Nietzsche); immanence must be made “pure.” Laruelle points to something like the “system error” of philosophy—but even in Laruelle I sense the same sort of one-upmanship that seems to persist throughout the history of Western philosophy: There’s a problem with past philosophers’ systemization of life and thought—and I’m going to solve it. Also like the characters in your novels, I sometimes find the so-called “theological turn” in philosophy appealing. I’m thinking of Emmanuel Levinas and the possibility of perceiving “a trace of divinity in the face of the Other.” I’m also thinking of friends, including the friends in your novel.

There’s this beautiful movement at the end of Nietzsche and the Burbs that finds the group of friends taking LSD and heading out into woods together. Preceding their trip, Art makes an off-hand reference to neuroplasticity: “We’re going to remake our brains—collectively. The brain is plastic, man—it’s plastic.” And during the trip, Art suggests that the friends might become “spiritual terrorists … joyful terrorists.” You speak above of “the descent, the morning after … the vague nihilistic desire to say no to the world” that follows such an experience, but I’d like to believe that the brains of these characters are indeed plastic enough to be remade according to the terms of a Levinasian phenomenology: a revelation of the Other as the “primordial phenomenon of gentleness,” a perception of one’s “infinite responsibility” for the Other. Am I being naïve in my desire to sympathize with Art? Does the final movement of Nietzsche and the Burbs depict the friends’ approach toward an active and affirmative nihilism?

Iyer: Now we get to the heart of the matter. I waver on the question of the relationship between transcendence and immanence. Sometimes I’d like to say I’m a good immanentist, like so many recent philosophers. But sometimes I feel a notion of transcendence is indispensable.

Let me explain. The teen characters of my novel are the equivalent of the “higher men” of the fourth part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra who, although creative and ambitious, have succumbed to various temptations which prevent them from affirming the suburban world in which they live as immanently worthwhile.

My character Art, for example, mishmashes scraps of older religions — from supposed Tantric Buddhism, ascetic anti-worldly Christianity, Gnosticism and pagan Earth-worship into an uneasy whole. Merv builds Minecraft cock-palaces in his bedroom and reads Anne Frank. Paula yearns to exit the suburbs for a queer bohemia. Chandra simply wants to destroy everything.

For my Nietzsche, Art and the other teens should affirm their suburban reality just as it is, in its immanent plenitude and autonomy, without attempting to distract themselves from it. They should really experience their suburban despair, giving nihilism its head, thereby allowing it to be completed and possibly overcome.

My Nietzsche undertakes his own attempt to transfigure the suburbs, recording his experiences on his blog. He notes that the suburbs seem to slip out of phase with themselves, to double up. His psychogeography of the burbs shows him how their transparency, even their insignificance, can grow opaque, thick. He discovers a kind of temporal lag or slowness which means the suburbs never quite catch up with themselves, and a spatial sprawl that can never be quite contained.

You mention Levinas, who was a close friend of the thinker and writer Maurice Blanchot. They both develop the idea of what they call the “there is,” a primordial chaos that lurks “behind” the ordered world of particulars. Levinas does so philosophically, and Blanchot does so in his fiction and in his literary criticism. I understand the double or image of the suburbs as exactly this “there is.”

For both thinkers, this “density of the void” (Levinas), this “night without truth” (Blanchot) is a constant threat to order and intelligibility. Our world is fragile; we cannot depend upon the distinctions and limits that structure our experience.

Levinas and Blanchot differ on the significance of the “there is.” Levinas fears it, arguing that only the relation to the other person can save us from the truth of immanence, thereby grounding our experience and opening up an ordered and intelligible world. Only the transcendent relation to the other person — “the primordial phenomenon of gentleness” — will allow us to push the “there is” to the edges of our experience.

Blanchot is more equivocal about the “there is,” embracing its impersonality in his accounts of literary creativity and in his literary writing itself. For him, it is experienced through a loss of agency, a movement from the first person “I” to the anonymous third person. This experience — if it can be called such — is the condition of the possibility of literary authorship, and can be made to echo in literary language itself. (Blanchot will also suggest that the relation to the other person can also be understood in terms of the “there is” — a difficult claim I’ve sought to understand in my philosophical work.)

No idea in literature and philosophy has been more suggestive to me than the “there is” as it is encountered in Levinas and Blanchot — in a philosopher and in a literary writer (there’s the question of the relationship between literature and philosophy again!). It lies at the heart of my account of “non-thinking” in the Spurious trilogy, and of the relationship between W. and Lars.

I first came across the work of Blanchot after I left university, living in the same suburbs as my characters. I had graduated into a recession, work was sporadic and I spent much of my time in Reading University Library, a few miles from my home, which was open to anyone, and gave me my first sustained contact with continental philosophy. I happened upon Blanchot’s famous “Primal Scene” in a book by Hélène Cixous, in which he describes an experience of the “there is” when a young boy grows weary and looks up at the sky.

What happens then: the sky, the same sky, suddenly open, absolutely black and absolutely empty, revealing (as though the pane had broken) such an absence that all has since always and forevermore been lost therein — so lost that therein is affirmed and dissolved the vertiginous knowledge that nothing is what there is, and first of all nothing beyond.

I was persuaded at once that it pointed to something fundamental in suburban life — in my suburban life …

I often dream of finding myself back in the suburbs, back before I received my PhD scholarship to pursue my studies in continental philosophy — before I could return to Manchester and leave the suburbs behind. And I dream of the strange expansiveness of the suburbs too — of their very indefiniteness, the way they seem to sprawl forever.

I used to go cycling under the white skies, and air felt thick and heavy. But I could never leave the menace behind — that “eternullity,” as Blanchot calls it; that “infinite wearing away.”

It is this “eternullity” that is, I think, so difficult to affirm. What would have happened if I’d never found my way into Reading University Library, if I’d never discovered continental philosophy, if I’d never won my scholarship and moved away?

There is, I think, another, ghostly life of mine that I’d never have the strength to affirm, in which I would have stayed stranded in those afternoons, alone with the “infinite wearing away” that belonged to them. (In the Spurious novels, W. explicitly admires Lars for his endurance of “eternullity” in long periods of unemployment; this, for W., is the source of Lars’s “non-thinking.”) Perhaps there can be a kind of beatitude of the suburbs as they give unto the void. Blanchot hints that this might be the case in his depiction of the “primal scene.” But there is danger, too. Too much nothingness can drive you mad.

My point is that my Nietzsche’s affirmation of the suburbs would include too much. He undergoes his own version of the “primal scene,” where he has a vision similar to that of Blanchot’s child. This is what leads him to want to say yes to the immanence of the suburbs as such, just as they are. But it is very difficult to affirm the “infinite wearing away,” because there is the risk of dissolution in the very anonymity of the “there is.” No wonder my Nietzsche ends up in a locked ward …

Levinas tells us we can hold the “there is” at bay only through our transcendent relation to the other person. Perhaps he is right, and that such a relation might have saved my Nietzsche. Nietzsche’s close only to his girlfriend, Lou, and when he loses her, he loses his purchase on the world. Nothingness comes to claim him.

My other characters are not so unfortunate. They have each other. Friendship always saves people in my work. So long as you can say, “this is the end” to someone, it is not the end. Even the “there is” is endurable in company.

You ask me about the status of the characters’ ecstatic experience at the end of the novel. They’ve taken LSD. They’re high as kites, and full of wild plans for the future.

The anthropologist Victor Turner developed a fascinating notion of communitas, a radically egalitarian, non-hierarchical community of “associative friendship.” Communitas, Turner explains, can never last; its liberatory joy must inevitably give way to a restoration of order. But, for a time, a rapturous holiday from “societas” was possible — a vacation from familiar social bonds and roles, the usual hierarchies. Communitas, lived anarchy, might well be understood as temporary overcoming of nihilism — albeit one that can never be definitively completed.

This takes us back to the apocalyptic laughter with which I began our interview. Filled with such laughter, communitas might become a form of life akin to the “dancing star” that Nietzsche invokes. Sure, farcical life awaits — there will be hangovers the next morning, as well as the consolations of black humor. But the joy of communitas might renew societas, changing the way we live on the inevitable day after. This would be the “plasticity” you mention, which might lead us to a new ethos, akin, perhaps, to what the late Mark Fisher called “acid communism.”