First Sentences or Paragraphs #5: Best European Fiction 2010 Edition

[series note: This post is the fifth of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

“Albania is a country where no one ever dies.”

– from The Country Where No One Ever Dies, Ornela Vorpsi

“If I had urinated immediately after breakfast, the mob would never have burnt down the orphanage.”

– “The Orphan and the Mob,” Julian Gough

“A cousin of mine had an aquarium built on her terrace, a rather imposing tank where strange, exotic sea creatures amused themselves in the company of all sorts of local specimen, destined to be eaten.”

– from While Sleeping, Antonio Fian READ MORE >

The xerox machine: printing press of the people

Karen Lillis is currently serializing a memoir about working at St. Mark’s Bookshop called Bagging The Beats At Midnight: Confessions of an Indie Bookstore Clerk over at Undie Press. Her recent installment, titled “People Who Led Me to Self-Publishing,” discusses the inspiring and energetic figures she encountered, people who took artistic matters into their own hands by making sloppy, lo-fi xeroxed booklets that were sold on a special consignment rack at St. Mark’s. Karen reminds us that writers such as Anais Nin, William Blake, Walt Whitman, Kathy Acker, Gertrude Stein, and others all self-published at one point. There’s a certain magic about it—the immediacy of it, the openness, the way any wing nut or fanatic or obsessive outsider can be given an equal hearing on the consignment rack. No filtration or editorial process—just print, copy, distribute.

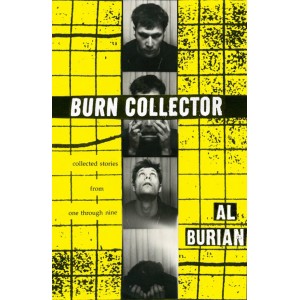

In a recent email I sent to Al Burian, I wrote that I was interested in bridging the gap between the small press/indie publishing world and the self-publishing/zine world. Al is kind of a cult figure in the self-publishing world, but is probably virtually unknown to small press and indie lit readers (although he did get some kind of honorable mention in The Best American Nonrequired Reading series one year). I’ve been reading his zines since I was 13 and I’m still totally obsessed with them. Since Al Burian was my favorite zine writer, over the years I let everyone I knew borrow his writings—teachers, friends, family. Some instantly became obsessive fans of his work as well. Since last month Al’s out-of-print collection of early zines, titled Burn Collector, is finally back in print after being republished by PM Press. (You should check it out—I’ve probably read it more times than any other book in my life.) Al’s zine Burn Collector and others like his inspired me to start self-publishing when I was 15.

In a recent email I sent to Al Burian, I wrote that I was interested in bridging the gap between the small press/indie publishing world and the self-publishing/zine world. Al is kind of a cult figure in the self-publishing world, but is probably virtually unknown to small press and indie lit readers (although he did get some kind of honorable mention in The Best American Nonrequired Reading series one year). I’ve been reading his zines since I was 13 and I’m still totally obsessed with them. Since Al Burian was my favorite zine writer, over the years I let everyone I knew borrow his writings—teachers, friends, family. Some instantly became obsessive fans of his work as well. Since last month Al’s out-of-print collection of early zines, titled Burn Collector, is finally back in print after being republished by PM Press. (You should check it out—I’ve probably read it more times than any other book in my life.) Al’s zine Burn Collector and others like his inspired me to start self-publishing when I was 15.

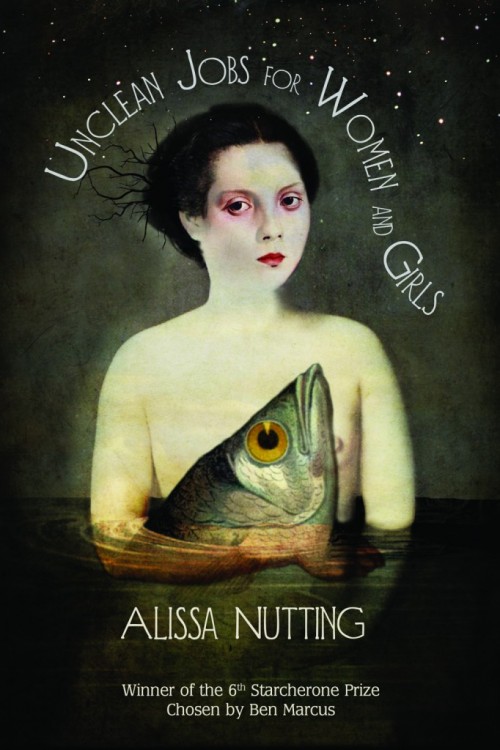

On Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls by Alissa Nutting

I love a book with a good title. I love good titles in general. When I’m bored, I sit around writing titles, placing each one in its own Word file so when I feel like writing but want to work on something new, I just need to look at all those empty, waiting documents, pick the one with the title that intrigues me the most, and start writing. Ever since I first heard of Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls by Alissa Nutting (Starcherone Books), I have been charmed by the title and I finally had the chance to really sit down with the book. I ended up reading it one sitting because it was one of those books you literally cannot put down. The stories in this collection are smart and imaginative and strange and fearless in their execution. It is readily evident why this book won the Starcherone Prize for Innovative Fiction. A great deal of care and handling went into these stories.

I love a book with a good title. I love good titles in general. When I’m bored, I sit around writing titles, placing each one in its own Word file so when I feel like writing but want to work on something new, I just need to look at all those empty, waiting documents, pick the one with the title that intrigues me the most, and start writing. Ever since I first heard of Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls by Alissa Nutting (Starcherone Books), I have been charmed by the title and I finally had the chance to really sit down with the book. I ended up reading it one sitting because it was one of those books you literally cannot put down. The stories in this collection are smart and imaginative and strange and fearless in their execution. It is readily evident why this book won the Starcherone Prize for Innovative Fiction. A great deal of care and handling went into these stories.

In Contemporary American Novelists of the Absurd, Charles Harris writes, “The absurdist vision may be defined as the belief that we are trapped in a meaningless universe and that neither God nor man, theology nor philosophy, can make sense of the human condition.” As I’ve read about Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls over the past couple months, I’ve often seen references to the writing as absurdist fiction. I would disagree. While many of the stories have a surreal, almost absurd quality to them, the stories by no means imply that they are a response to a belief that we are trapped in a meaningless universe because so many of the characters in these stories are clinging to the hope that there is, indeed, some meaning in the universe. In each of these stories, Nutting is, above all making beautiful sense of the human condition.

December 15th, 2010 / 5:03 pm

Actually I Like That Bulgakov Book With the Dog But No One Comments Unless Things Are Contentious

What is the most exciting non-human creature in your novel? Mine is a capybara. If you say “dog” or “adorable dog” or “talking dog” then you are everything that’s wrong with contemporary literature.

Peter Handke on American Writers

Generously translated and sent by Paul Buchholz.

ZEIT: Do you like American writers?HANDKE: Not the recent ones. I’m always thinking again: how wonderful literature would be without all these period-, family- and society-novels. [Theodor] Fontane could maybe still do that, but today it’s a form of sagging culture. I translated Walker Percy, The Last Gentlemen and The Moviegoer, that is a great author. And I love Thomas Wolfe, his novel Look Homeward, Angel. These books have something lyrical, that is absolutely a part of them. With Jonathan Franzen for instance it doesn’t appear at all. He follows a knitting pattern, a scheme. Philip Roth is in the end only a master of ceremonies. But reading is an adventure. In a book, also in a society novel, its seeking movement has to be there in the language. There is no epic literature without a lyrical element. But that has completely disappeared from American literature. There have to be outbreaks, a controlled letting-oneself-go, not this recipe-like writing. Something has to emit from the author, whether that comes from his being lost or from his pain. When, with an author, one only sees the making–to avoid the word Mache [style]–that’s not enough.

What is Experimental Literature? {pt. 2}

Settle thy studies, Faustus, and begin

To sound the depth of that thou wilt profess:

Having commenc’d, be a divine in shew,

Yet level at the end of every art,

And live and die in Aristotle’s works.— Christopher Marlowe, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (1604)

One way to think about experimental literature would be to consider it in relation to conventional literature. Which begs the question: what is conventional literature? The answer to that question is much easier than the answer to the titular question of this post. The answer is this: conventional literature is that which follows Aristotelian prescription. Plain and simple. So if you want to know what experimental literature is, you might begin by considering it to be that which deviates from Aristotelian prescription.

Brian Evenson illuminates the problem of Aristotle’s suffocating influence in this great essay called “Notes on Fiction and Philosophy” in this amazing collection of literary criticism called Fiction’s Present: Situating Contemporary Narrative Innovation (SUNY Press, 2008), at the beginning of which he suggests:

[T]o move to an understanding of late twentieth- early twenty-first-century fiction, the first step is to move out of the fourth century BC: to let go of the Aristotelian notions that still dominate most thinking about fiction in writing workshops today…Discussions of setting, plot, character, theme, and so on, their parameters derived from Aristotle, seem hardly to have advanced beyond New Criticism’s neo-Aristotelianism; and when a workshop student says “I didn’t find the character believable,” usually the model for believability is firmly entrenched in nineteenth-century notions of consistency that have probably less to do with how real twenty-first century people act (not to mention nineteenth-century people) than with specific, and often dated, literary conventions.

I’d like to use this quote from Evenson as my jumping off point.

@ The New York Observer, Matthew Hunte weighs in on the newly printed 20 Under 40: Stories from the New Yorker anthology: “Instead of highlighting new talent, they inadvertently end up championing precocity and nurturing a culture where early recognition and promise are conflated with achievement.”

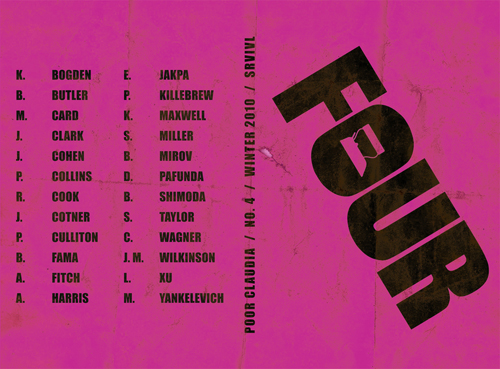

Poor Claudia 4 ++

The fourth issue of Portlandian magazine and press Poor Claudia is alive:

More specs and info and purchase points are available here.

Or, if you are smart and thrifty, you can involve yourself in the PC Subscription Package, which includes for $30 everything PC will release in 2011, including two issues of the journal, chapbooks, nonbooks, broadsides, and more.

While you’re at it, the back catalog is teeming, and all beautiful crafted objects: James Gendron’s Money Poems and Emily Kendal Frey’s Frances are both in particular fantastic.

“There Are Three Dead People In Me”

Emily Kendal Frey is a poet I like. She lives in Portland, Oregon and teaches at Portland Community College. She is the author three chapbooks: Airport (Blue Hour 2009), Frances (Poor Claudia 2010), and The New Planet (Mindmade Books 2010). A full-length collection, The Grief Performance, was selected by Rae Armantrout for the 2010 Cleveland State University First Book Prize, and is forthcoming in the spring of 2011. A new series, Sorrow Arrow, appears in regular installments at Ink Node.

Here is a new poem, [A HISTORY OF KNIVES]:

When I met you we were the shape of salt shakers. I married my dad and threw him in the ocean. I dragged him along the bottom as he filled with salt. I opened my legs and a grasshopper was there. Your first home was a house on stilts with butter dishes READ MORE >