25 Points: Fjords Vol. 1

Fjords Vol. 1

Fjords Vol. 1

by Zachary Schomburg

Black Ocean, 2012

72 pages / $14.95 buy from Black Ocean

1. Fjords Vol. 1 is something I could have read in a few hours—easy.

2. It took me 17 days to read Fjords Vol. 1 all the way thru.

3. Fjords Vol. 1 is 57 pages.

4. I have been fascinated/infatuated by Zachary Schomburg-stuff for quite some time. I sent him an email once but he never replied. I assume this is because he was too busy writing awesome fucking poetry.

5. If I wrote awesome fucking poetry like Zachary Schomburg, I probably wouldn’t have the time to reply to emails from people I have never met IRL.

6. It’s not very hard to read Fjords Vol. 1, which is nice. But it’s also not meant to be very hard, I don’t think. It’s like something that is easy to learn but hard to master. Like chess, for example. Or swimming. The Tecktonik dance. I don’t know. (But) that’s how I feel about Zachary Schomburg poetry.

7. If Fjords Vol. 1 had been a homework assignment in high school, I would have found it to be very easy. You could definitely read it all in one night/sitting (if you really wanted to, and I sort of allude to this already).

8. But there is so much to understand and feel and grasp and learn and write down and think about—which is why I love Fjords Vol. 1 so much.

9. Like the poem Staring Problem, in its entirety. “A woman walks into a room. I am in a different room. What has happened to your eyes? she asks.”

10. I feel like, maybe, sometimes, Zachary Schomburg is too smart for me to understand—but I generally feel like this about all poetry—so I keep reading the same line over and over, because I keep thinking “No, this is not hard. I am making it hard. I am pretty sure I can understand anything,” and even after several re-readings (now)—I still cannot grasp everything there is to grasp in the book. That’s fine though. And this is not a bad cannot-grasp-everything. This is a good cannot-grasp-everything. A book that is challenging (to/for) me. Something I can come back to, later in life, after I have read more books and feel like I can finally maybe understand things better. READ MORE >

February 26th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

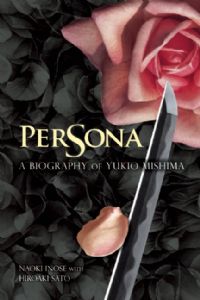

Persona, a newly-released English translation of Yukio Mishima’s biography.

Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

by Naoki Inose and Hiroaki Sato

Stone Bridge Press, January 2013

864 pages / $39.95 Buy from Stone Bridge Press or Amazon

“Perfect purity is possible if you turn your life into a line of poetry written with a splash of blood.” – Yukio Mishima, Runaway Horses

This review—or my interest in the new Yukio Mishima biography Persona coming out from Stone Bridge Press and in Mishima himself—began as these things often do, in a coffee shop with a like-minded friend discussing the rather awesome notion that Japan has a forest devoted almost entirely to suicide. The Aokigahara has associations both with Japanese demonology, and suicide primarily as it’s the second-most popular place on earth to end it all; falling behind in rank to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. I believe the conversation started out discussing the Foxconn suicides and sort of snowballed from there, until mention of Akira Kurosawa’s attempt after the commercial failure of his Dodes’ka-den by me led to my friend’s mention of Yukio Mishima. Unlike Kurosawa, Mishima actually finished the job, committing the ritual act of Seppuku after a failed coup when he was only 45.

I’ve always been attracted to stories like this, as many people—I think–are. Suicide, homicide, sudden outbursts of lunacy by the likes of Jackson Pollock or Norman Mailer have always had a nostalgic twinge for me and I decided then to pursue Mishima’s fiction. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, probably my favorite of Mishima’s books, holds a similar allure to Kurosawa’s cinema, being as it is a contemporary art form describing events long ago made history. His sense of minimalism and terse descriptions of landscapes, conversations, friendships, and the mythological air of Japan in 1400 is like nothing I’ve ever read, and when word of Persona came round, I was certain I had to review it.

I’ve come to expect biographies to fall into two categories if they are in the first place good, or well-written. The first would be relegated to public figures who did not in their lifetime write a great deal or put out some form of art or conversation and hence the biographies tend to concern themselves with familial goings-on, schooling and at-length descriptions of important/pivotal events, and attempted portraits of physical moments in the biographee’s life to create something that’s readable, and fits into the mandates of a narrative the public can enjoy/become informed from. The second is for everyone else; the artists, writers, conversationalists and politicians who made no quarrel with sharing their views with the world and were gleefully recorded by an adoring, or deploring, public.

Persona, as it is a portrait of an actor, an artist, a poet, a playwright, a film director, and any number of other things in the political arena who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature not once, but three times, falls somewhere between these two templates for an enjoyable, and effective portrait of the man.

February 25th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 1: What is a concept?

Sol LeWitt: “Wall Drawing #1111: A Circle with Broken Bands of Color” (2003, detail). Photo by Jason Stec.

[Update: Part 2 is here.]

I wrote about this to some extent here, but I wanted to expound on the issue in what I hope is a more coherent form. Because I frequently see concepts confused with constraints, and the Oulipo lumped in with conceptual writing. For instance, this entry at Poets.org, “A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry,” states:

One direct predecessor of contemporary conceptual writing is Oulipo (l’Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a writers’ group interested in experimenting with different forms of literary constraint, represented by writers like Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, and Raymound Queneau. One example of an Oulipean constraint is the N + 7 procedure, in which each word in an original text is replaced with the word which appears seven entries below it in a dictionary. Other key influences cited include John Cage’s and Jackson Mac Low’s chance operations, as well as the Brazilian concrete poetry movement.

I would argue that the Oulipo, historically speaking, are not conceptual writers/artists—although it’s easy to see how that confusion has come about, because the Oulipians have proposed some conceptual techniques, such as N+7 (which I’d argue is not a constraint). (Also, it’s each noun that gets replaced, not each word.)

What, then, distinguishes concepts from constraints? And why does that distinction matter? In this series of posts, I’ll try answering those questions, starting with what we mean when we call art conceptual.

I heartily encourage you to read Virginia Konchan’s newly published story “Welcome to My Harem” (at Joyland), as well as her other stories and poems, linked to here.

Lingering Questions: A Review of Marjorie Stein’s An Atlas of Lost Causes

An Atlas of Lost Causes

An Atlas of Lost Causes

by Marjorie Stein

November 2011, Kelsey Street Press

112 pages / $16.00 Buy from Kelsey Street Press or SPD

As the title suggests, An Atlas of Lost Causes is a bound collection (and a documentary of sorts) that includes map-like textual matter, in the form of poetry and illustrations. On the surface, it reads as a story about the death of a twin told through narrative poems and letters but the story unfolds as the living twin struggles to uncover the mysterious circumstances surrounding her sister’s death. Conversely, beneath the surface this collection is a relative confession told in reverse by an unnamed narrator and made evident through the “cartoon-like drawing[s]” and the “mere thought experiment” (61). In beautifully written prose-style vignettes, Marjorie Stein allows us to journey with her characters as the memories shift between the past and present, all the while tethered to the narrator’s search for self, now that she is without her twin.

Using everyday details and scenarios, the darkness inside each poem serves to tell the story of what can happen when the desire to learn the cause of death is more important than mourning the one who died. Each poem seems to attempt exploration of a life’s memories as they begin to erase themselves. At its core, An Atlas of Lost Causes is the story of a twin searching for her own identity and reason to live by retracing the life of her dead sister.

The narrator presents a layered flow of rational and irrational thoughts dotted with interruptions of childhood memories, past experiences that she believes are hers, but could easily have been her sister’s, and vague meditations that sometimes morph into hauntingly alluring images that pull the reader from place to place and moment to moment in a reversed mapping of death. Fueled by a barrage of interrogation style questions, each of the seven “chapters” gets us (and the narrator) closer to “Day Zero.” The questions in the book grow in number as they do in life when we contemplate an unexplained death. “What are these words but shadow puppets dependent upon an opposite wall?” “What is the story?” “Have we any further to go?” “Did she mean to?” “Intent or accident?” “How could I know what happened?” “What has this to do with the problem at hand?” “Who wants to be the last one in line when the lights go out?”

February 22nd, 2013 / 12:00 pm

David Shields in Conversation: Notes from the Highly Self-conscious Rat Lab

Discussed:

-David Shields = highly self-conscious lab rat; David Shields = Canada

-Will the internet ever save anyone’s life?

-Bret Easton Ellis’s twitter feed

Catherine Lacey: I read How Literature Saved My Life during a two-week period when my only exposure to the internet was responding to a few emails on my phone. I read almost a book a day. It felt like it was saving my life. Since then my disdain/distrust of the internet seems to grow every day and your book made me remember, in a way, why. When I got to the list of fifty-five works you swear by, I realized that of all the works I find the most admirable, very few of them came to be online. And yet I have spent a lot of time reading things online, disproportionate to the enjoyment or worth I’ve found here. In light of this book and Reality Hunger, I’m curious about how you use the internet.

David Shields: I use the internet as a tool to figure out where the war is being waged that day on our individual and collective minds.

Catherine: Specifically, what websites and what kind of content? News? I’m assuming you still read books, too?

David: I read books almost entirely offline. Stuff online: I just follow what links come in to me and I explore them. There are no websites I return to in any predictable way.

Catherine: When I read Reality Hunger in 2009 I think I was feeling more positive about the possibilities and influence that the internet was having on literature, but now I’m not so sure. Am I just turning into a crank? I am starting to get the feeling that the brevity and quick turnaround time of internet publishing is not our friend. Do you think it is our friend?

David: Hmm. Internet publishing. Not sure I even know what that is. You mean the way you can write an article and it will be up on the web within minutes?

Catherine: I mean exactly that. The immediacy of online magazines.

David: Not hugely crucial to me—this aspect. I’m not running a newspaper. I’m trying to write books that will alter how people think in 20 years. Seems to me that we’re not quite there yet with internet publishing. I’m virtually certain that within a generation—if not much sooner—publishing as we know it will be no longer, and my sense is that any decentralization of publishing, any removal of the middleman, is good. It’s more chaos-making, but it’s largely for the good. I gather you were/are writing a book about religion, and you may have religious impulses that I don’t have. I have zero drive toward anything beyond this; there is nothing beyond the world of humans as nature and animals—and so if this is the particular chaos that we occupy now, it’s no more and no less “meaningful” than the chaos occupied by our ancient amoeba-ancestors. READ MORE >

Dear Apple Store on 103 Prince Street,

I hate you.

You aren’t really a store that sells technological appliances (though really you are). But really you are a late 80s/early 90s San Francisco-style bathhouse that sponsors unprotected sodomy orgies 24/7 and even on holidays, like Presidents’ Day.

Stop being so bisexual, Brooklyn, weird, and a host of other disgusting symbols.

PS, Baby Jong-il hates you too.

That’s Cool: Whole Beast Rag

Nowadays, I feel like half the turdburgers calling themselves editors are convinced that having a couple hundred Facebook likes equates to having a “successful” lit journal (whatever the fuck “success” means is beyond me, because really, who gives a shit about lit journals nowadays). I wonder if those lames realize how easy it is for me to hide their notifications so I can see the important things, like which one of my hoodrat friends is listening to 2 Chainz on Spotify.

Well, anyway, props to Grace Littlefield and Katharine Hargreaves of Whole Beast Rag, which is not a lame lit journal. I met these DABs in Chicago last year, where Katharine gave me her business card (boss alert!) so I could stalk her on Facebook. Back then, they were two doughy-eyed kids from Minneapolis with some big ideas; now they’re on the West Coast, making moves like Suge Knight. They’ve integrated themselves into the LA art scene, and have put together two incredible, beautifully-designed issues for both web and print.

25 Points: The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral

The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral

The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral

edited by Joshua Corey and G.C. Waldrep

Ahsahta Press, 2012

576 pages / $28.00 buy from Ahsahta Press or SPD

1. The Arcadia Project is not in the least a conclusive project, but rather quite inconclusive. As stated in the Introduction: “an anthology such as this one must be a living and motile assemblage.”

2. Editors Joshua Corey and G.C. Waldrep do not contribute any of their own poetic work. This cuts both ways, as while it shows a measure of humility on the parts of any editor not to grandstand it is also nearly always worth having an editor’s own work (if existent) on hand for clarity of comparison’s sake within the presentation of any selection. How a poet writes interestingly reflects on how a poet reads.

3. Corey pens the Introduction, attesting: “certain tendencies are discernible in the work presented here, all of it first published after 1995” and that “Postmodern pastoral offers a means of mapping the shifting terrain of that world while maintaining its ethical consciousness that the map must never be mistaken for the territory.”

4. Waldrep doesn’t add one word of his own to the book itself. But elsewhere: http://arcadiaproject.net/the-woods-the-technology/ He offers up that it was questions such as:

Which factored into how the anthology came to be, and he adds:

Between 2008 and 2011 Josh and I sifted through hundreds of books—published since 1995 by North American writers, generously defined—as well as hundreds of submissions that came in over our electronic transom, looking for work that would guide us into the forest and try to show us something: work that would leave us alone together (in or in spite of our discrete alonenesses); work that challenged us and terrified us and moved us, that spoke to or around or from within our ecological predicament as 21st-century human creatures.

The resulting anthology is not meant to be definitive, rather provocative and generative, an early draft version of an ongoing conversation between a wide array of poets and the world we live in.

5. The lack of having any such editorial presentation of the framework behind the book’s conception within the book itself feels a disservice to readers.

6. As presented, there’s little tying together of these texts. They are left as isolated cries in a wilderness of language.

7. Poems are divided into four sections: “New Transcendentalisms,” “Textual Ecologies,” “Local Powers,” and “Necro/Pastoral” without any explicit rendering of what may or may not be meant by any of these broadly inclusive and quite permeable categorizations.

8. Questions linger, such as why not include some prose? Both statements of any kind from contributors and/or fiction, non-fiction, or works of theoretical positioning.

9. There’s a band but no bandwagon. Dozens of wheels but no cart.

10. As a reader I yearn to relate these texts in some way. To locate some vein or—what one feels is heard as a bad word by many poets these days—tradition within which the work does participate and indeed does seek continue. Of course doing so may prove some “Romantic inheritances” unavoidable. READ MORE >

February 20th, 2013 / 12:09 pm