An Ethic by Christina Davis

An Ethic

An Ethic

by Christina Davis

Nightboat Books, March 2013

68 pages / $15.95 Buy from Nightboat Books or SPD

We live in an era of the performed self. Where ideology once hailed, Kim Kardashian now smiles. From reality TV to Facebook, from Snapchatting to every form of text- or image-based avatar, a sense of self—or, more precisely, senses of selves—depends on a technologically mediated audience for its/their existence. Yet the more this exhibitionism is transmitted via technology, the more it’s datamined, subjected to surveillance, snooped on—what’s at first innocently called “sharing.” This sharing is usually connected with something to sell, even if it’s a selling of self, while the civic modes of rhetoric are all shot through with profit. No wonder leisure time is in such short supply and represented by a sleep-deprived Miley Cyrus. But that’s because, ultimately, she doesn’t own anything, either.

The opening poem of Christina Davis’s An Ethic contains the apt observation, “only the long illusion we are landlord,” echoing a postcolonial ethics of learning to be a stranger in the place where you were born—non-nativist. When everything has been taken, and then taken away (Freud’s “fort/da” game without the “da”), it becomes the new categorical imperative of sorts to step out of this process. This isn’t a question of scarcity, because the world is already too much, which is why the mostly unconscious perceptual-ideological filters exist to keep it at bay. An Ethic speaks of an entirety, an enormity, and yet does so in a reticent language and sparse poems, as no matter how hard they try to enter this world fully, a shared world, a world shared before “sharing,” before you try to convince me that you have what I need, a nagging gnosticism haunts them. It’s the animals wearing crowns, but all crowns, as Sleigh Bells anthemically chant, get set on the ground.

I said to the man, “I do not know

if I am a good

or a bad.” He said, “To be a good person

you must first be a great animal.”

And so I let the crawl

come unto me.

This is when the body ceases to be a container, when the walls do fall, but only because of a proximity to death: the death of the/her father early in Davis’s book, the seeming destruction of everything when a home disappears, or bodies naked and craving a momentary extinguishing. An Ethic teeters on this abyss, with one foot pointed out of this world while the mother’s voice calls the subject back, or else it’s the words of surrogate fathers: Oppen, Eliot, Whitman, Seferis, Thoreau. In fact, I can’t remember a book of poetry filled with so many parental figures, as opposed to, say, the parents confessional poets like to complain about, which I think partially explains Davis’s reserve. “The father” only ever grudgingly gives permission to speak; “the mother” only ever provides an illusory shelter from the war, the war every father brings home from the war, the father as colony.

Yet the hesitancy in Davis’s language is also a precision in addressing the book’s fundamental concerns: not the outline of an ethic, but freedom and constraint, love (filial, erotic) and loss, the apparatus of power threaded through every aspect of life—down to the micro-bio—except for the thick grass that absorbs the corpse. It’s the wettest part of Davis’s at times eerily Dickinsonian poems that have clearly been chiseled, reworked, are almost flinty as a result of the time it takes to make them, a beautiful care and attention, which is an ethic of its own, the poem as impossible “grail- / stone,” because ethics are easy in space, and more difficult in time. Give me room, and I can be very good (which isn’t the same as well behaved); give me time, and I can be even better. But these days, everyone’s time is spent earning money just to pay the rent or buy a bigger flat screen TV. The entirety of Davis’s poem “Dissent” reads: “In the kingdom / of images, the blink // is the infidel—.” Post-Sphinx, Oedipus gouged out his eyes when he discovered that he had killed his father and slept with his mother. Those existing separate from the realm of myth only get to do one of those.

October 21st, 2013 / 11:00 am

(Canadian) Sunday Service: Andrew Faulkner poem

NOTE: Canadian poetry! For no particular reason, I am taking over Melissa Broder’s column for the month of the October to spotlight poems by contemporary Canadian writers. Today’s poet is Andrew Faulkner, whose (rad) debut collection, Need Machine, was published last Spring by Coach House.

Acknowledge Your Sources

It was a sky-draped year. We collected data like habits,

stockpiled information to have something to look into.

We were all about identity. Our primary theme was abstraction –

I know, right? With small words we touched it, and with big words

we brought it home. At a right-wing party’s office, a bomb explodes.

At a leftist rally, something something. It was the year Heidegger

walked among us and seemed especially deep. Like, at the bottom.

A little red light signalled some really important shit.

As a gift to individualism, I eschewed the individual.

As a gift to myself, I learned to hail a cab like a flower

bending towards the newly departed. We kissed strangers,

stayed up late, depended on discipline to save the day.

That summer Justin Bieber insinuated himself into your heart

like an undercover agent. The Insurgencies of Love topped all

the charts. It was a good year for wanting and my stocks did well.

But you thought I’d gone all art deco in the mind

and the four-roomed apartment we’d claimed as ours

was a little too …something for you.

You were raging for pastels. You wanted to move. So we spent

those eighteen months in a mid-sized European city whose transit

map, when crumpled, resembled a once-popular cognitive theory.

We tried to avoid cancer like the plague.

We wanted a sky the colour of a painting,

any painting, just something you don’t have to think about.

One Saturday God went out, left us $20 for pizza

and said He’d be back in the morning.

The point was that we could have done anything.

Friends stood before us like a porchlight that night

and we fought over who would ring the doorbell.

You began writing letters to Jennifer Aniston

but in a really, like, political way.

As in, between two people.

Dear, no one’s mind is right.

But then you left exactly how all the sad songs said you would

and I moved into a hotel the way a fastball chooses the mitt

it’s tossed to: the glove’s there and there’s throwing to be done.

For a while, the world was everything in my suitcase.

The morning rose up like a Parisian mob, made unreasonable

demands, then settled in for an afternoon coffee. Or café, as they say.

In terms of currently accepted physics I was pretty fucking sad.

There were birds. I made my heart into the shape of the moon,

or perhaps it was the other way around,

but you must have seen my longing in the sky

because you came back. God helps those He really likes,

as Benjamin Franklin used to say.

I was coming down with something.

Beset with symptoms, I gave up style with panache.

That is: with panache, I gave up style. I tied my tie up tight.

Is there a doctor in the house? Drumroll, punchline, drumfill.

But, seriously, is there?

Because I’m finding it hard to breathe.

Andrew Faulkner co-curates The Emergency Response Unit, a chapbook press. He is the author of two chapbooks, including Useful Knots and How To Tie Them, which was shortlisted for the bpNichol Chapbook Award. Need Machine (Coach House Books, 2013) is his first full-length collection. He lives in Marmora, Ontario.

selling 10 original sexts for charity. each sext costs $10, except for one of them — level 2 — which costs $1000.

Baby Marie-Antoinette Opens Up Upon Simone Weil, Gang Rape, and More

Last week, I published a tiny story by Baby Marie-Antoinette, one that was titled Gang Rape Me Now Please.

Then, last nighttime, while the world acted woeful (as usual), Baby Marie-Antoinette sent me a telegram, telling me that she had things to say to me.

When a girl who, at less than 42 months, already has a biopic starring the striking Kirsten Dunst wishes to say things to you, then obviously you heed that.

That’s what I did.

In a vintage skirt (because boys can clad themselves in skirts) and a St. Louis Cardinals sweater (because they’re the best baseball team ever, and the LA Dodgers are gay), I met Baby Marie-Antoinette (as well as her mommy) at a McDonald’s in Midtown.

Baby Marie-Antoinette munched on a vanilla ice cream cone. I did the same.

BMA (Baby Marie-Antoinette): Thank you very much for meeting me.

Me (M): You’re very welcome.

BMA: My mommy articulated that it’d be agreeable if I articulated further about gang rape and such, and I agreed.

M: K…

BMA: So… you should probably inquire further…

M: Why are you so struck by gang rape?

BMA: I don’t believe in autonomy, freedom of speech, freedom in general, liberty, individual rights, or any such stuff.

M: Why?

BMA: I am Catholic. I absolutely believe in God, as God will make it so that I am the Queen of France. God cares for me. Another girl who God cares for is Simone Weil. She is a French girl who is sort of looked down upon because she didn’t spend her nights at white people bars on the Lower East Side.

M: What does that mean?

BMA: She didn’t got nuts for the human body or anything that humans nowadays (or in the olden days) deem progress. In Simone’s notebooks, she states, “We possess nothing in this word other than the power to say ‘I.’ This is what we must yield up to God.” For Simone, all the rights that people are roaring for are abhorrent. They are as unheavenly as a croissant without warm cherry cream in the center. According to Simone, “The self is only a shadow projected by sin and errors which blocks God light.”

M: So even though America says the self is the splendidest form ever; really, it’s sordidness.

BMA: Uh-huh. So when the self is destroyed, and when the attributes attributed to selfhood are tossed into the trash, it’s not naughty for God, it’s naughty for the ideologies that promulgate free personhoods.

M: Like the United States of America.

BMA: That’s a country that’s corrupted by personhood. In Gravity and Grace, Simone says, “We have to be nothing in order to be in our right place.” But Americans advocate the antithesis. They try terribly hard to be something, which is why they talk so much, eat so much, spend so much, and make so much trash.

M: But really, this “something” isn’t “something”; really, this “something” is “nothing,” only a different kind of nothing than what Simone is referring to, as it’s a nothing that has nothing to do with God, and thus it’s meaningless.

BMA: Sigh.

M: So why does 24/7/365 gang rape stay on your mind?

BMA: Because with gang rape it’s boy after boy being utterly uncaring about your body and what you yourself want to do with it. Simone says in her notebooks, “The more I efface myself, the more God is present in the world.” I could try to terminate myself, but that seems so self-involved, so I’d rather have boys do it. According to Simone, “When the ‘I’ actually is abased, we know that we are not that.” I know that my body is not nice. A pink and fuzzy Miu Miu coat is nice. But flesh, like Simone says, is “vile.”

M: Maybe the reason why gang rape is regarded as one of the top revolting behaviors in the world is because so much of the world cares about their bodies and not about God.

BMA: Uh-huh, people nowadays seem to be invariably promoting themselves, especially on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and any other gay social media platform designed by California loser. Simone says, “There is a lack of grace with the proud man.” Does Sheryl Sandberg possess grace? No. She’d likely be really upset if boys gang-raped her.

M: But what about those who equate !@@$% with purity?

BMA: These types should read John Milton’s play, Comus.

M: I read that play while I ate a chocolate cupcake.

BMA: My mommy read it to me while I ate a raspberry cupcake.

M: It’s about a girl who’s lost in the woods and is danger of being raped by a monster.

BMA: But even if the monster did rape her, it couldn’t corrupt her, because her purity isn’t positioned in her skin.

M: Perchance this is why Baby George III says Sasha Grey is more religious than Adrienne Rich. Baby George III saw Ariana Reines’s lecture at NYU a while ago, and during the question and answer, she compared Jesus to porn starlets, since both are renown for being transfixed by myriad external elements.

BMA: Perchance… The reason why gang rape is regarded as it is is because the world is wrought with utterly unthinking ungracefulness.

This is when Baby Marie-Antoinette asked her mommy to purchase her another vanilla ice cream come.

On Varamo by César Aira

Varamo

Varamo

by César Aira

Translated by Chris Andrews

New Directions, Feb 2012

144 pages / $ Buy from Amazon or New Directions

“Long long ago, in the continuum of the world’s reality, two random objects were set apart by a radical heterogeneity. A difference so irreducible no concept could embrace both things. No term except Being. That was how Being came into being, and from then on thought and philosophy existed too, at least until that afternoon in Panama…” when everything came to a halt for an idea. Part creation myth and part scathing satire, the narrator of Varamo is a hilariously tedious literary critic who is telling the story of a ‘bubble in time’ in the life of a government employee. Emphasized as an ‘exception without precent or sequel’, the reader is entered into a moment when the present is made discontinuous with the history and future of the institutions which impose upon time.

The narrator, who tasks herself with revealing the ‘process of inspiration’ behind the protagonist’s masterwork poem “Song of the Virgin Boy,” speculates that on this afternoon in 1923, that the ‘end of thought’ might be at hand, when the eponymous protagonist of Cesar Aira’s Varamo is paid his government salary in counterfeit money. The end of thought?… “But if people didn’t think, how would they occupy their time?” she then asks, a sentence that has plausible attribution to either her or Varamo, whose perspective is so intimate to the narrator’s consciousness as to make him seem the victim of a novella-length coercion. These moments occur often in Aíra’s work; questions arise from the circumstances expressed by the material of plot, but the thrust is orthogonal to the story and lands square on the lived experience of the reader. But the coercion is compelling for the reader, inasmuch as they can detect the parallels in the chosen narration and the metaphorical content of the staged actions.

The imposition of the impossible here does not beset Varamo except at the level of not being able to change his bills, which difficulty is solved serendipitously by the intervention of a publisher interested in his idea. The other impossibility is in the task upon which the narrator sets forth: the total recuperation of the material circumstances of inspiration, drawn from the text of a poem by the protagonist which is left coyly outside the reader’s purview. The free indirect discourse deployed throughout is used to persuade readers that the circuitry of events presently recreated is utterly deduced from the text of Varamo’s poem, a cheap mock-up of one among many idle fantasies of the lit-critical enterprise. Many have picked up on how Aíra is making a sort of sincere mockery of such a project in the novel, but the plausibility achieved in the narration [free indirect discourse, and not coincidentally, throughout], combined with its positioning in time, belies something more than a stylist at work, and tells a tale about the keeping of time in the era before the atomic clock, which never loses a beat.

What seems more interesting than admiring Aíra’s prodigious output and consistently uncanny sense of humor, is the examination of the book that attempts a view of its regard for and situation within chronological time. Aíra’s most recent critical work Las Tres Fechas argues for the importance of the dates of production and of publication, as well as the period of life from which subject matter is drawn, as integral to the reading of so-called minor writers. Varamo was finished in 1999, published in 2002, and the events contained happen in 1923, years that fall conspicuously about one decade before major economic collapses. But dates can only be held up under the premise that time is continuous, that years stand in relation to others and can be be brought into a dialectical relationship with each other. A strange thing Aíra does in Varamo is craft a narrator and story which resist this idea rather strongly. The book takes place in the course of the day, and the ‘act of invention,’ because it occurs in the hours past midnight when birds resemble dark clouds in the sky, is treated as an event that goes without saying. Because the text of the poem is part of common sense curriculum which is second-nature for all SouthAmerican schoolchildren in this universe. There is something that is eerily glossy about the narrator, who is oblivious to the interval between the Panamanian optimism of 1923 and the half-century of military intrusion which culminated with Noriega.

October 18th, 2013 / 11:05 am

Hothouse by Tex Kerschen

Hothouse

Hothouse

by Tex Kerschen

2011

84 pages / Free for download here

“Selections from the hothouse of the possible,” says the epigram to Tex Kerschen’s poetry collection, Hothouse. Recently, when I saw Kerschen read in Houston, he was accompanied by an opera singer, a six-year-old, a video installation and a smoke machine. As you might expect, he’s a gifted showman. That said, the possible Kerschen’s referring to doesn’t allude to stagecraft or even poetry, per se. Kerschen’s more ambitious than that. He wants to trick his readers into reconsidering what is possible.

It’s a soft sell. “Salvation sells itself,” these poems seem to say. “All I do is the paperwork.”

When Hothouse’s poems talk they drawl, unbalancing the reader with prolonged vowel sounds of narrative abstraction. At times they hold the reader at arm’s length; at times whisper in the reader’s ear with a hand in their hip pocket. By this sleight of hand Kerschen’s poems can look other than they are – seeming character studies in fatalism before surprising the reader with the possibility of redemption. They document the failings of human virtue and the plight of the human animal who toils and scratches in the aisles of 99 Cents Only Stores; searches for squandered youth in the clubs of Houston or Dublin to the ballads of Chamillionaire; retreats to the escapist fantasy of the Renaissance Festival and finds only wench-cleavage, neo-nazis and rigged jousting. But the purpose of this cataloging of human suffering is not, in fact, to simply bum you out. Like all good satire, it’s aim in enumerating humanity’s worst qualities is the restoration of human goodness: “I was all like / Where my dogs at? / They was all like, /At the pound / in a cage / waiting for a pinprick, / send magazines.”

Through Kerschen’s satirization of suffering – the probable, the predictable and the probably happening to the reader right now – the reader reevaluates how much more may be possible. In the process, some measure of convalescence from suffering is accomplished; as in the poem “Past Lives,” where several levels of narrative framing are at work to set up a joke, which may or may not be at the reader’s expense. The poem’s narrator recounts the high times had in Cleopatra’s court: “She was famous. I was rich. We traded gifts / of gold, lions and slaves.” When the listener (né reader) inquires about their own past life, they become the punchline: “Yes, you were there / You were cleaning up.” The direct address here implicates the reader in the poem, and thereby in the poem’s critique. Jokes on you. As Nietzsche’d say: only humans laugh, because only humans suffer so goddamn much they need a fucking laugh.

In Kerschen’s poems we suffer, because we know; and because we know, we can overcome suffering. But we don’t know everything, or more so, don’t allow ourselves to. Kerschen ties our unconscious knowing to animal instinct, signified in the bestiary of animals parading through these poems. Wild-life is a thing to be kept in check, a side of ourselves we to be suppressed. It’s the beard which grows back unbidden and must be shaved down anew each day, the dog in the cage. And yet it’s also this un-house-trainable aspect which offers emancipation from the cage; as an unexpected dolphin sighting does for two young lovers sitting on the beach burying their cigarette butts in the sand: “… I looked out at the water / and bit my tongue before telling you we wouldn’t / see dolphins, and there they were / beyond the swells / swimming in pairs / diving to eat / rising to breathe.” Kerschen, if not quite seeking reintegration, does encourage communion. “How many words should fit / on a line in a poem? / The time for half measures / has passed. Chance won’t see / that the dog gets fed.” The narrator hungers to know. The dog knows. It knows it’s hungry. But the only way either will eat Snausages tonight is to get a little work done.

October 18th, 2013 / 11:00 am

You don’t have to write. You don’t need it like the air. You do have a choice. You could stop at any time. In all likelihood, no one would be sorry if you did. It would be fine. It might even make you happier. And isn’t that all for the best? Wouldn’t you rather choose how to spend your only life than have it chosen for you?

The one semester I was lucky enough to teach creative writing, the last project I gave my students was to make the most beautiful thing they could imagine. Practically no one wrote a story or a poem. Someone is giving you the same assignment.

The Desert Places

The Desert Places

The Desert Places

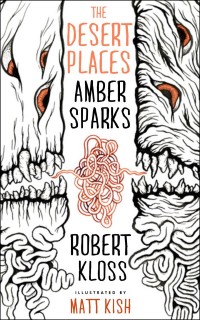

by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss, illustrated by Matt Kish

Curbside Splendor Publishing, 2013

84 pages / $10.60 buy from Amazon

Rating: 8.5

Evil is ubiquitous. It’s in the best literature and (as I present it to my students) it is the reason why humanity needs literature: as relief from evil and as elucidation for evil. The Desert Places, the new hybrid text by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss, with illustrations by Matt Kish, depicts the history of malevolence from primordial Earth all the way into a nightmarish technological future. Plenty of other narratives have depicted the fall and subsequent struggle of Lucifer, Chamcha, Grendel, et al., but what sets Sparks’s and Kloss’s narrative apart is its broad scope within such a slim package. READ MORE >

October 17th, 2013 / 6:06 pm