25 Points: TheNewerYork

The Weekender 3-Pack

The Weekender 3-Pack

by TheNewerYork

240 pages / $22.00 buy from TheNewerYork

1. There is a market (and when I say this I mean like, a common, growing… need, among readers) for very brief literature. This is not news for the twitter generation, the HTMLGIANT community, or internet writers. But, it bears repeating. We need things smaller.

2. As much as we need things short, we also need them to be deep. No!–we need some of it deep. We also need some of it funny and purejoy. We need some of it confusing. We need unsettling. We need beautiful, and we need deep.

3. TheNewerYork pours these parts (mostly equally) into the 70-some pages of each of their three journals (Book 0, Book 2, and Book 3–Book 4 is forthcoming this year). It’s this wildly interesting, thoughtful, colorful, ugly, pretty, stupid, weird. It’s equal parts smile-inducing and vomit-inducing. And no single piece of experimental fiction in these collections goes over two pages in length.

4. When it comes to literature, TNY is like those bags full of halloween-sized candies. You want two or three at a time, you reach in, and take what you get. Some skittles, some m&ms, some fucking Almond Joy (ugh!), and every once and awhile a severed finger, a used condom, a sticky note with the answer to life written on it.

5. Aside from length and diversity, these pieces share at their fundamental bottom new forms of storytelling. David Foster Wallace solidified for us how fragmented culture/life/reality/consciousness is thanks to…well everything that constitutes society and its structures. Now our writers are taking up these little fragments and painting pictures of them, one at a time. Or, they are picking up a fragment (picture a shard of glass AS A SYMBOL for some little fragment or waste of society) and painting not it, but with it. With the colors the fragment contains. These pieces of literature are some of them the canvas and some of them the tool, the brush, the color, the pen.

6. Okay enough bullshit. These issues are fantastic. They entertain me very much. They make it fun to read.

7. These are perfect for reading on a lunch break, or during a 15 minute break in the middle morning or late afternoon. Like, I have trouble bringing novels with me places and really getting into them during short, unpredictable moments throughout the day. Like, for me, the novel I read in bed each night is not something I’m taking with me in the bathroom, or to work, or on the train. I have found that these short pieces are so concisely packed with thought and contemporaryness (?) that they’re as entertaining, emotional, and thought-provoking as anything I could be doing with a spare 6 minutes. That’s right, I said it. Thought-provoking.

8. With that said, I did read all of issue 2 (in 3 chunks) while in the passenger seat of my girlfriend’s car on a 5 hour drive home after Christmas.

9. And, it’s the only ‘book’ I’ve been able to read in a car, without puking or even wanting to.

10. And, I’ve picked up that same issue six times since Christmas, flipping open to a random spot and reliving some freaky or funny tale which, as I re-read, I can feel becoming as real an artistic comfort to me as a Books album, or Season 9 of Seinfeld. READ MORE >

February 18th, 2014 / 6:33 pm

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#14)

TJ Lyons is in California doing things that dudes usually do. His first book, Things, will be out soon from somewhere awesome. Things are always what they seem. tjisadude.tumblr.com

I think I sleep in a peel that fits me better than a collar

by

T.J. Lyons

This poem came from my experience living as a banana in a Safeway for nine days before the produce people noticed me, and then they marked me down. An old woman with a pegleg bought me. This will appear soon in the ebook, The Wind Cannot Remove the Stench in My Bones, with art by Andrew Jurado.

in a Safeway for nine days before the produce people noticed me, and then they marked me down. An old woman with a pegleg bought me. This will appear soon in the ebook, The Wind Cannot Remove the Stench in My Bones, with art by Andrew Jurado.

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

February 17th, 2014 / 11:26 pm

Forthcoming: Don Dreams and I Dream by Leah Umansky

Leah Umansky’s poems have been published or are forthcoming in POETRY, Thrush, Maggy, Barrow Street, and elsewhere. Her first book, Domestic Uncertainties, was released by BlazeVOX last year. She writes interviews for Tin House and articles for Luna Luna Magazine.

Kattywompus Press is releasing her new chapbook, Don Dreams and I Dream, later this month. The collection of poems is inspired by Mad Men, and the show acts as a charming frame for Umansky’s primary thematic interests: womanhood, beauty, and desire.

February 17th, 2014 / 6:11 pm

Interview with Marek Waldorf

Braver than most, Marek Waldorf has dared to spin literature out of the terrifying realm of political speechwriting. His debut novel, The Short Fall (Turtle Point Press), follows a speechwriter for a presidential campaign who has been left disabled after a botched attempt on the nominee’s life. In dense, lyrical prose, the narrator explores the campaign from its nascent form to the disastrous present, winding in and out of events as they lead his body to cross paths with the assassin’s bullet. If you think you’re up for a Bernhard-style treatment of American political rhetoric and its relationship to authenticity, idealism, and image making, then look no further. Marek was kind enough to answer some questions for HTMLGIANT via email.

***

Hal Hlavinka: In your professional life, you write grants for nonprofits like Girls Write Now. I’m interested in how your day-to-day contact with bureaucratese informed the lexical and logical frameworks of The Short Fall. More specifically, as the speechwriter’s paranoia unfolds, we start to read all sorts of fragmentary beliefs about the relationship between language and charisma, politics and fundraising, and I wonder to what degree these connections are carved from your day job.

Marek Waldorf: Grantwriting’s unusual in that you’re writing for a literally captive audience. Foundation officers are paid to read what you’re paid to write, allowing more freedom to be boring than, say, speechwriting or marketing. The latter I have very little understanding of. To be honest, I hadn’t moved into fundraising when writing The Short Fall—I was still a temp. But does the job involve more linguistic depletion than other writing professions? I don’t think we do too much damage: at one funder’s meeting I recently attended, grant applicants were encouraged to “step free of the jargon zone.” I’ll travel in & out of the zone fairly regularly, but I’m also—maybe more—interested in the infantilizing uses of language.

And TSF is less an immersion in bureaucratese than a recounting—a very long thought-balloon—of how people function within such immersion: the self-justifications, pretty stories, petty (&-not-so) delusions. There’s a recurring joke in TSF—particularly, section two—where the speechwriter spends pages explaining his craft & straining mightily on the pot of composition all in the service of (for instance) “A new day is rising in America.” Or let’s just say—one man’s unique susceptibility to language & its gaming.

HH: At your reading in Chicago, you mentioned that part of your strategy for writing The Short Fall, at least in the beginning, was to explore the narrator’s voice inside a dense, elliptical framework in the style of Thomas Bernhard. Can you talk a little bit about the challenges and benefits of using Bernhard’s notoriously demanding narrative aesthetic as a guide?

MW: Bernhard’s The Lime Works was a driving influence for sure—his books sort of cocoon the period of TSF’s writing. And, yes, I’ve often wondered about your well-taken second point. I worried Bernhard’s aesthetic wasn’t something you dabble in, that it demanded a lifelong engagement, but—fortunately for the book—I was chafing as well, right from the start. While there’s a show-off quality, an exuberance, to Bernhard’s style, it’s not one he conjures up at the level of “turning a phrase.” Whereas I can’t help myself. Two books I read during that period—Nicholson Baker’s U & I and Alexander Theroux’s An Adultery—seemed like masterful and disrespectful negotiations of that aesthetic (as is, I believe, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be). To see distinctive work occupying the same ground that wasn’t pastiche—resemblances surfacing almost as matters of temperament—was reassuring. Of course TSF is also pulling hard in the direction of the American maximalist novel of disintegration. The politics, the stamp of its ambition, the presiding question of authenticity—all contrive to keep it on native soil.

HH: You began writing the novel in the nineties, only to finish it over a decade and two presidencies later. To what extent did your writing change—first with the Lewinsky scandal, followed by the disastrous Bush tenures, and finally the bittersweet state of the Obama administration—as the office and image of the POTUS has changed?

MW: I had TSF pretty much finished by 1995, so it is interesting to see what’s changed since I wrote the book, and what’s stayed the same, given the 20-year gap. The Society of Victims, for example, started life as a pun-laden left jab—watching it metastatize within the real world vs. the book has been interesting. And the emphasis on a politics of infantilization worked out well it seems … witness our progression to ubiquitous bathroom-acronyms like POTUS & SCOTUS! I’ll say this about political and science fiction, having attempted both—prescience ranks among their highest virtues. But mostly I feel the oddness of returning to something written by a much younger me. Its youthfulness detains me, and when I write about it now, I feel a bit like an impostor.

My hope at the time was TSF would welcome a certain type of reader, which wouldn’t necessarily track to how s/he voted. I’m not sure I succeeded entirely, but I believe the pressure of that instinct—to abstract out of partisan politics—was helpful. In retrospect, the Clintonian triangulating which led many of my peers to cynical despair &/or a vote for Nader feels like TSF’s operational baseline. The politics of encroachment-from-the-middle isn’t what’s happening now—Bush certainly changed that—but it’s due for a comeback, I imagine, and it doesn’t matter for the book, because the narrator has burrowed so deep into the campaign he doesn’t see Vance as up against anybody—only chance—and the idea of an alternative arises in terms of rhetorical tactics … as deployment, a trick. My aim in all this wasn’t ambiguity so much as an absence, like everything else below the neck the speechwriter can’t move or feel. Like SCOTUS, he’s all head.

Innovation by Carl Chudyk

Innovation

Innovation

by Carl Chudyk

Asmadi Games, 2010

$25 Buy from Amazon or Asmadi Games or try online at Isotropic

Writing [Blue/Age 1/Bulb]: Draw a 2.

It doesn’t look like much on its own, but that small amount of information tells you everything you need to know about one of the most monumental achievements in human history. It’s just one example of 105 concepts and technologies represented in Carl Chudyk’s clever (and occasionally revelatory) minimalistic card game Innovation.

Of course, being as it is an exploration of the march of human progress from Prehistory through the Information Age, Innovation is minimalistic only on its surface. The goal of the game, reduced to its simplest format, is to harness these advancing concepts to steer your culture (represented by a tableau of cards in front of you) toward monumental achievements—specifically, more and faster achievements than the other players. Ideas from The Wheel to The Internet are represented by the intersection, on a single card, of four very simple elements: a color (one of five, which might be thought of as the card’s suit); a value (the age, 1-10, that the invention hails from); a “dogma” effect, which can be called upon once the card has been “melded,” or put into play; and three icons, of one or more of 8 types, arranged around the bottom-left borders of the card like a supine L.

In play, the clipart-style icons and mostly solid colors make Innovation redolent of a child’s educational toy. From the outside, that is. In play—that is, to those actually experiencing the game—Innovation‘s minimalistic trappings hide a maximalistic struggle as epic as history itself.

Let’s take another look at Writing, for example. It’s an Age 1, or Prehistoric, technology. During setup, stacks representing all 10 Ages of history, each holding roughly 10 cards, are arranged in order. All players begin in Age 1, and can only begin drawing cards from the later ages once the Age 1 draw pile is depleted or if they have melded (added to their tableau) a technology from a later age. Since cards from later ages are almost universally more valuable than earlier ones, this makes that simple Writing technology, whose only effect is “Draw a 2”, the key to unlocking a host of strategic choices for the lucky player who draws it early in the game. While the other players are stuck in the Stone Age, discovering important but rudimentary technologies like Sailing, Pottery and Domestication, you can be drawing Age 2 (Classical era) technologies such as Mapmaking, Currency and Mathematics.

Let’s take another look at Writing, for example. It’s an Age 1, or Prehistoric, technology. During setup, stacks representing all 10 Ages of history, each holding roughly 10 cards, are arranged in order. All players begin in Age 1, and can only begin drawing cards from the later ages once the Age 1 draw pile is depleted or if they have melded (added to their tableau) a technology from a later age. Since cards from later ages are almost universally more valuable than earlier ones, this makes that simple Writing technology, whose only effect is “Draw a 2”, the key to unlocking a host of strategic choices for the lucky player who draws it early in the game. While the other players are stuck in the Stone Age, discovering important but rudimentary technologies like Sailing, Pottery and Domestication, you can be drawing Age 2 (Classical era) technologies such as Mapmaking, Currency and Mathematics.

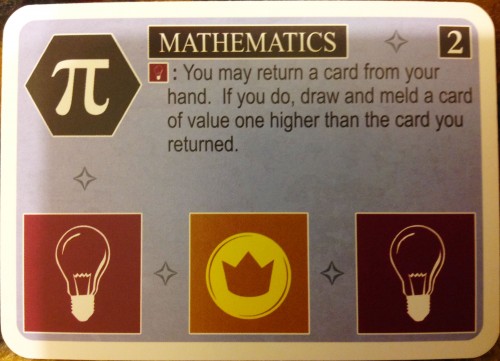

And once you have Mathematics in hand…oh, the places you’ll go then. Like Writing, Mathematics is a blue card with 2 bulb icons and 1 crown icon. Unlike Writing, it is an Age 2 technology, which means that as soon as it’s melded into your culture, you can draw from the Classical era’s suite of concepts even without Writing’s culture-advancing abilities. In fact, you couldn’t use Writing anymore if you wanted to; when you put Mathematic into play, you placed it on top of a stack of all other technologies of the same color you had previously discovered, burying them and making their dogma effect unusable. You could say that the advent of Mathematics pushed Writing out of the limelight. It’s still a part of your culture, but for now, its effects are dormant.

That doesn’t matter, though, because Mathematics’ dogma effect is even more powerful than Writing’s. It reads: “You may return a card from your hand. If you do, draw and meld a card of value one higher than the card you returned.” Again, this might not look like much at first. But let’s not forget the reason you melded Mathematics in the first place: you always get to draw from the age matching the highest-value card (determined by the card’s Age) in your culture. So you can use Mathematics to discard another Age 2 technology, like Monotheism (who needs religious mystery in the age of rationalism?) and replace it with something from Age 3 (the Medieval era)—say, Engineering. On your next turn, you can draw a new Medieval card, then immediately exchange it for something from Age 4, the Renaissance. And you can keep doing this to rocket through the ages, one turn at a time, discovering Banking and Refrigeration and Quantum Theory while your rivals are still puzzling out Road Building.

Tread cautiously, though. While early technologies are slow but stable, later technologies can be volatile. Even Writing, while it doesn’t provide the same rocket boost as Mathematics, has the advantage of being somewhat more contemplative and circumspect. With Mathematics, you must meld the card that you drew, even if it buries another technology you would rather have. Writing is slower, but it allows you to examine and judge for yourself exactly how and when to put your ideas into action.

February 17th, 2014 / 11:00 am

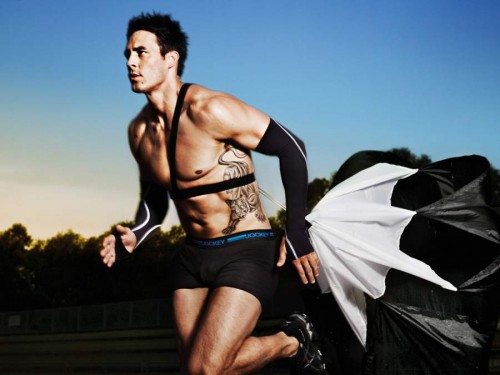

Sports Writing Snippet (1)

***

“Johnson sliced through South Africa the way a blade goes through a perfect fillet steak. He cut through the quivering hunk of meat, showing no mercy to the tendons and muscle fibres that once held it together and exposed sparsely cooked flesh.”

— Firdose Moonda, at espncricinfo.com, describing Australian Cricket fast bowler Mitchell Johnson.

(Cricket, fyi, is sometimes called “The Gentleman’s Game”)

***

Short Edited by Alan Ziegler

Short: An International Anthology of Five Centuries of Short-Short Stories, Prose Poems, Brief Essays, and Other Short Prose Forms

Short: An International Anthology of Five Centuries of Short-Short Stories, Prose Poems, Brief Essays, and Other Short Prose Forms

Edited by Alan Ziegler

Persea Books

354 pages / $16.95 Buy from Amazon

I realize now that the only thing you can do with any anthology is take issue with it: who was included, who wasn’t, what order they’re in, why there’s more x than y. But before I step into the trenches, I want to note right off the bat that Short is an important and impressive document. It comes at a time when the short form, especially in its incarnation as “hybrid genre,” is gaining traction both in indie and (to a lesser extent) mainstream circles. I need not list presses like Tarpaulin Sky and Rose Metal Press; authors as different as Lydia Davis and Amelia Gray; lit mags like NANO Fiction and Gigantic. And that’s just a very small, very indie cross-section. Hell, Sentence already lived a full life and closed its doors.

Point is, I shouldn’t have to convince you that understanding the evolution of very short prose is an important project for the contemporary literary landscape. And it seems that Alan Ziegler, editor of Short, is the right man for the job. On his resume, besides his own books of “tales” and “takes,” is having taught Short Prose Forms at Columbia since 1989. That’s a long time.

Of course, here’s where the bones-to-pick start coming in. Ziegler’s definition of “short” is a little different from what mine might be: 1,250 words is his limit, which allows writing up to four pages to make it into Short. I can’t help but think that some of the pieces at the upper limit of this mark—Donald Barthelme’s happily tooting “The King of Jazz,” for example—cease to be short a few hundred words before their end.

If I was looking to criticize, I might take issue with the treatment of the pieces too: they’re printed one after another, with almost no whitespace. I understand that this is a logistical measure, and the anthology couldn’t house nearly the number of pieces it does if each piece were given its own page. Still, the purist in me argues that fewer, better-presented pieces would be more effectual than more works, smashed into the same space. Such a large part of reading very short prose is having the visual space to consider it after its textual work is done; reading Short is a little like reading Shakespeare in one of those two-column tiny-print Collected Works volumes.

Then again, such are the casualties of reading an anthology cover-to-cover. Those shorts which originally appeared in a full book of such pieces appear bizarre and sort of hamstrung out of their context. Amelia Gray’s, for example, the last one in the anthology, doesn’t carry nearly the pleasure as when you read it in the context of AM/PM as a whole. “Remain Healthy All Day,” it begins, before its laundry list of odd directives. If we didn’t know better, we might think she was being glib. But in the original, wonderful edition from featherproof, we’ve already begun the everyday tragedies of our friends Terrence and Charles and see, through their eyes, the direness of being asked to “Use a warm towel to dry the cat.”

This strange, decontextualized nature of the anthology might partially be remedied, I thought, by changing the order of the pieces. Ziegler orders them according to the birthdate of their authors; we start at Girolamo Cardano’s “Those Things in Which I Take Pleasure” (1501) and end with Gray. The shorts take on an often similar thrust to those with which they are surrounded, then. The beginning is full of fairly staid ruminations, which pick up speed as we pass through Poe and Baudelaire and reach a cruising altitude more amenable to the contemporary palate with writers born after 1925, to whom the second half of the book is devoted. I appreciated the alternative jaunt through literary history but perhaps, I wondered, the crowdedness of this volume might be better suited to a random sequence—by first initial of last name, for example. Then the close juxtaposition of pieces, instead of being tiresome and chronological, might be fortuitous and on any given page point to a sort of conversation across the ages. What an artistic concept! All of them in a room together!

February 14th, 2014 / 10:00 am

HOW MUCH DOES IT COST? by Laura Warman

How Much Does it Cost?

How Much Does it Cost?

By Laura Warman

Cars Are Real, Oct 2013

82 Pages/ $15 Print or Free PDF. Purchase from SPD or download from Cars Are Real

I see Gen Y not just as a challenge, therefore,

but as a great opportunity We all shop

at Target but who is Mr. Target

Some readers will be tempted in the critical fervor of postmodern analysis to read into Laura Warman’s dry observations and blog-inspired style a derisive mockery of “Gen Y”. But HOW MUCH DOES IT COST? is not an indictment of the same internet culture from which it derives; it’s an embrace. These poems are not mocking the digital age. They are experiencing it. Warman writes “the only place left to cry is the Ross Park Mall”. Here, comedy is an element of sincerity. This—along with lines like “Money is the closest thing to poetry”—sets up havens of capitalism as the only places we can dispose of interpretive frameworks, thus allowing for experiences and feelings without analysis. We are enlightened enough that capitalism (which has a single end goal) is clear, giving the mall a purity which allows us to acknowledge ourselves as we are, simply, without a need to be coated in layers of metaphor and superfluous intellect.

This, of course, can lead us to sounding stupid. Confronting our actual thoughts, without window dressing, is something Warman does frequently. One of her poems:

2/Ouch

HAS ANYONE REALIZES YET THAT ALL

THE POEMS THAT MAKE ME SOUND

STUPID AREN’T SARCASM BUT

ACTUALLY ME SOUNDING STUPID

The most alluring thing about Warman’s poetry is that a learned person so consistently being honest sounds like a learned person trying to be funny (and it is funny!). Warman goes a long way to force intellectualism out from behind walls of carefully gathered thoughts meant to represent a person’s lived relation to the world. Concerns like drone warfare, alienation from labor, and feminism are intermingled with the same language that revels in text messages and Kim Kardashian.

Warman has her own walls. Some poems pre-empt criticism through tongue-in-cheek statements that give clear and self-aware observations of her tricks, tools, and failings, letting her write things like “there, now you can’t criticize me”. It’s a facetious move that makes the best of her poems harder to engage with. It’s the double-edge of a predictive wit; both veiled humor and directness, it leaves us amused but unsure. For all the assurance that her writing is not an affect—an obsession with the Kardashians and the mall enmeshed with political and cultural concerns—HOW MUCH DOES IT COST?is sometimes too funny and aware to seem anything but.

The ancient Greek skeptics used a laxative analogy to explain their use of philosophy. For them, philosophy, like all laxatives, causes itself and everything below it to be excreted, leaving a space for something new (or nothing at all). This, I think, is the power of HOW MUCH DOES IT COST?. Warman engages honestly with her connections to media, sex, corporations, labor, and day-to-day trivialities. She writes “there is nothing left but 705 channels” not with mockery but with dry precision—it disarms us, lets us experience the channels because there’s nothing else. By adopting the digital age sincerely as philosophy we are rid of a need to self-reflexively step back from our lived experience, thus giving us space to engage with it fully. HOW MUCH DOES IT COST? uses this experience as laxative, letting it pass through us, pushing down old frameworks of understanding and leaving space for something new. This makes it a book not only topical and entertaining, but radical.

I asked Laura Warman to respond to this review, paying particular attention to my critique of her sometimes defensive or affected writing style. Her reply follows.

LW: I put up walls for protection says each person when their dishonesty is revealed. But, maybe dishonesty is the new radical honesty. The more honest we are the more our thinking is compartmentalized, bought, and sold. The more dishonest I am, the more walls I put up, the less I am known and the more power I have to meditatively enclose myself in the mall, the car, the bedroom. Through meditation on capitalism I find my free space to Be, my comfortable form of radicalism.

I am afraid to be known. I hide behind “honesty”. Target knows I am pregnant before I know I am pregnant. (1) Honesty is a quality I can no longer possess because I am known more by corporations than I know myself. Honesty is terrifying because it represents something I do not possess. The television knew I needed a boyfriend before I did. The television knew women must be beautiful before I knew. I am playing a small role as possessor of body/ possessor of capital. My anarchy is fake. My dismissal of anything not feminist/ radical is meaningless. I still wake up to the punch clock, to the day at the Organic Grocery Store. I try to write to form radical change. But, I still only feel safe at the Ross Park Mall. This world wasn’t created for people who feel things. I cannot possess honesty, I can only reflect my place in a system that is growing out of control. The literal cost in How Much Does It Cost? is all of us who are not ready to make a radical change. It is we who want to walk down the street in short-shorts and not be harassed but instead accept silence. We who buy the “organic pork and the sprouted corn tortillas” and post about food-rights on our blog. We are the cost of the system. We were not first concerned with our comfortable spot, now the comfort is the Cost.

1. HTTP://WWW.NYTIMES.COM/2012/02/19/MAGAZINE/SHOPPING-HABITS.HTML?_R=1&

***

Joe Hogle lives in Pittsburgh, PA. He is also known as Ronny Cammareri, Mr. Weekend, poopsmithey, and The Love Guru. You can enjoy a hypertext story and read some of his poetry HERE.

February 14th, 2014 / 10:00 am

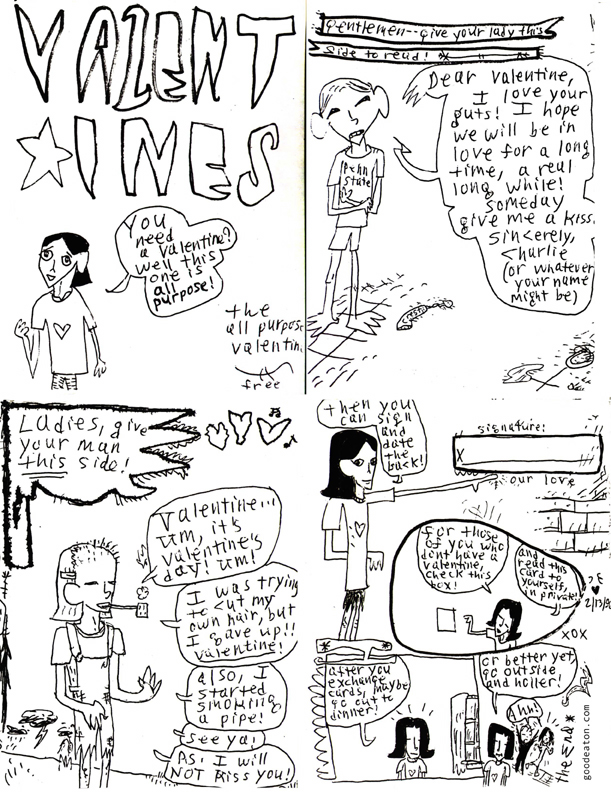

Tom Eaton’s Valentine

An oldie but goodie. (2/3/96? Sheesh!) Printable/foldable version here (PDF).

Happy Valentine’s Day, HG. Someday give me a kiss.

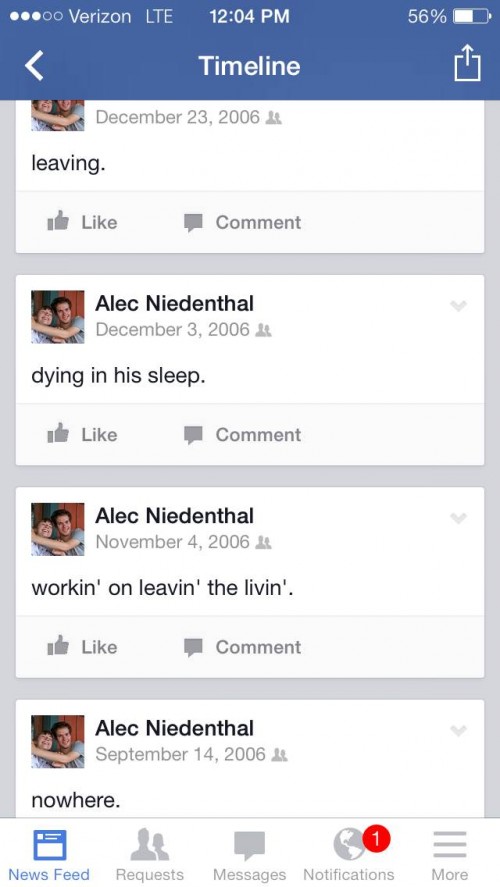

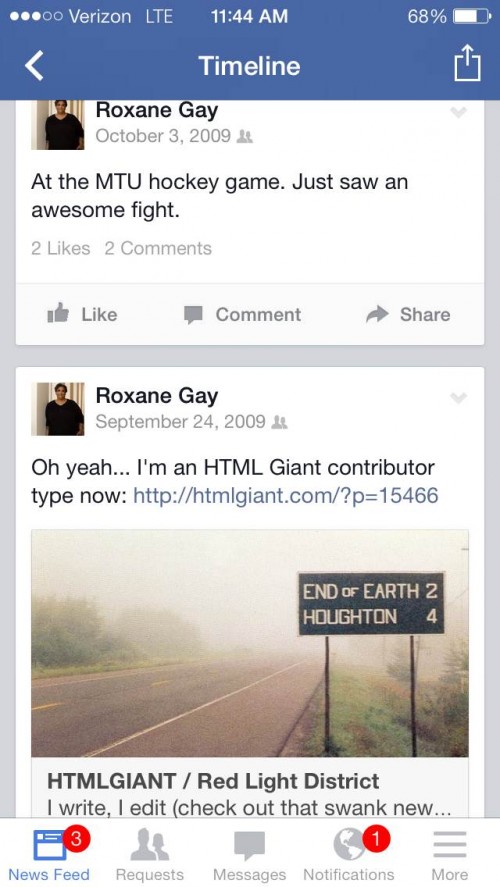

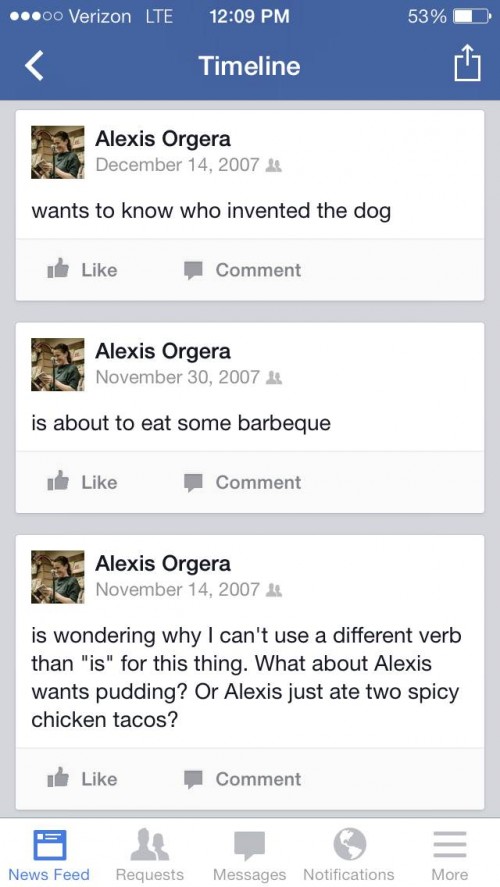

The HTMLGiant Contributor & Editor Facebook Movie, 2006-2009

We began with no fanfare:

We found our way:

We made promises we couldn’t keep:

We joined in:

We thought things over:

We were honest with ourselves:

We stood corrected:

We anticipated a trend: