Hustle by David Tomas Martinez

Hustle

Hustle

by David Tomas Martinez

Sarabande Books, May 2014

84 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon or Sarabande Books

Hustle, David Tomas Martinez’s debut book of poetry, is a cry from the street written with developed-over-time, intelligent style with pace the and moxie of a tom cat. The opening poem, placed even before the table of contents and dedication, “On Palomar Mountain” establishes a theme that will carry its way throughout this four part collection of poems as it begins, “The dark peoples things//for keys, coins, pencils / and pens our pockets grieve.” Those three things their pockets lack are the book’s foundation. Keys, coins, pencils and pens tell a story with nothing but “a lighter for a flashlight” that is begging to be told. It is the story of the bold but shed in a sensitive light as the poem ends with a “walk into the side of a Sunday night.”

While fairytale readers and romantic poets might object to Hustle’s style, those with their boots sunk deep in urban black-top pavement will resonated with the jazzy, up-beat rhythm of Martinez’s lines. Lines chopped short and neat with stanzas generally organized into few line bunches compliment the underlying sentiments of the words as the narrator (presumably Martinez himself) declares ownership of what is to be presented in the opening poem of section one:

A car want to be stolen,

the night desires to be revved,

will leave the door unlocked,

a key in the wheel well

or designedly dropped from a visor.

A window will always wink

to be broken by bits of spark plug

or jimmied down the glass.

This is mine.

Where is the window to break

Iin your life?…

Literally inviting the reader to break into the life of the story, Martinez teaches the reader to hot-wire, jimmy-rig, and break an entry into the rest of the book. Clearly, the man in in possession of a story that needs to be told. Have no doubts about it, this is Martinez’s own story. Collectively, the poems become a memoir, highlighting details of the poet’s life which some might find shocking coming from a well-spoken, educated individual.

To tell his story, Martinez organizes the book into four sections. In sections one and two, he continues with the themes that have been established in the beginning of the book while incorporating the facets of growing up ruff which are often overlooked. The importance of a (dis)functional family life, for example, is first mentioned in part II of “Calaveras”

Yes, families are supposed to be circuses.

Accept is, and accept that the acrobat’s taffy

of satin will twirl, and the bears in tutus will spin

over the exposes in the warped wood

and cracks in the waxy linoleum,

all the while your grandfather will yell

“You no like it, go in the canyon and eat tomatoes.”

June 30th, 2014 / 10:00 am

GUANTANAMO by Frank Smith, Trans. By Vanessa Place

GUANTANAMO

GUANTANAMO

by Frank Smith

Translated by Vanessa Place

Les Figues Press, July 2014

160 pages / $17 Buy from Les Figues or SPD

As a law student, I feel that the most important demographic that this book should reach is law students—but for various reasons, it will never reach them.

When reading Guantanamo, I thought back to my Constitutional Law class and our discussions of the constitutional rights of foreign nationals. We learned about the debate through the lens of Guantanamo, specifically Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRT), which was challenged on constitutional grounds. As the introduction of this book informs, prisoners in the U.S. are guaranteed habeus corpus relief from unlawful detention. Such relief is generally called for when there is no knowledge of charges by or evidence against the detained person.

The introduction by Mark Sanders talks about translation and how Frank Smith drafted this book in French based on actual interrogation reports. It implies that there is no text under the text, only layers of translation with no correct source document: not only is there the language barrier between the author and the interrogation, but there is also the communication barriers between the Middle Eastern citizens and the U.S. interrogators. Law is very much the same way in having no definitive text. It is a mosaic bible made and revised by humans, primarily rich white American men (even still!) in this country. And yet, those who endeavor to work in it have their very human blind spots, such as the war vet in class who did not want to reconcile with “terrorists” having rights—that the Supreme Court should not pander to terrorists in giving them due process in our courts of law.

The text itself revolves around a trinity of ambiguity, vegetables, and the United States of America. The ambiguity in the writing comes from the use of the French pronoun on to show the absurdity and inhumanity of Guantanamo’s process. You observer a recurring narrative that the reader is unsure of is two continuous characters or two general bodies: (1) “the terrorists”; and (2) “the administrative body conducting de facto trials.” Vanessa Place translates on in a variety of permissible ways depending on tone, or not, or maybe creating her own tone in an unsettling way. Sometimes we are pronounless.

Asks if has family ties with known terrorists in Pakistan.

Answers exactly what kind of ties?

Rephrases the question, asks if any relatives have ties to terrorists in Pakistan.

Answers has no family in Pakistan. How could this be?

States has “kin” who is a member of a terrorist group responsible for attacks in Uzbekistan.

Answers no one in the family has any connection with any terrorist group in Uzbekistan to speak of. (p. 3)

And so on. Not only does this stylistic choice call to attention the human machinery at work here, but it also creates a haunting, disorienting effect. Who are you supposed to believe? There is no human face that you are supposed to recognize here. There are combating facts which simply do not add up. And here, unlike the real U.S. criminal justice system (for all its flaws), there is no plea bargain to a lesser crime, there are no charges. Your reward for confessing to being an enemy combatant is to remain there, indefinitely, perhaps forever, even if really you were just growing vegetables, at the wrong place and at the wrong time.

The whole book goes like this, in deadpan call-and-response, with occasional breaks into a very sparse poetry, absent of any embellishment. It is not quite as dry as the interrogation proceeding, but only not quite.

“The man, his wife, and his mother still believed

they were being taken to Uzbekistan

but when they reached the other side of the river

a Tajik man informed them that they were actually

entering Afghanistan

and that they would have to fend for themselves,

that Tajikistan had effectively decided

to get rid of its Uzbek immigrants

Some families attempted to object

because they did not want to be abandoned there

but they were threatened with death

if they did not stop complaining.

The man believes they were then

in the area of Ahmed Shah Massoud.” (p. 53-4)

The author instead uses this break to tell the straightforward narrative of the de facto defendant(s), in broken up third-person prose, as if these defendants were not allowed to tell their stories directly and that the only voice which spoke for them was the voice of Allah. Their voices are suppressed, and simultaneously horrifying and bland. They are made bland. They are ruled by the farming of vegetables, caring for their families through agrarian life, until they are expulsed then tricked by ill-meaning “friends.” These narratives are frequent and often in this book, and probably in life too. Yet they are rendered “boring” and unaesthetic. I think this is important.

And at the end, nothing happens. Not in this book, or in the thing it is modeled after as conceptual art, until the shifting mind-mass of law went in the direction of abolishing the kangaroo courts, and setting some of the particulars free. The undangerous ones. Hopefully—but how are we supposed to know?

The worst kind of ambiguity, yet depicted flawlessly.

***

Rory Fleming is a rising third year law student at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He is also a writer of prose and poetry.

June 30th, 2014 / 10:00 am

How Are Publishing Genius Submissions Going?

I used to do occasional “inside baseball” posts about running a small press, like this one from four (!) years ago. I guess it’s been a while. I find them clarifying, and usually after I write one I change something about how I “do business.” With that in mind, here are some numbers and thoughts related to Publishing Genius’s book submissions currently and throughout history. This year’s open submission period ends at 11:59pm on Monday.

Last year Publishing Genius didn’t even have an open period, but that doesn’t mean that I didn’t accept books from submissions. It’s just that I was still working through 2012’s manuscripts. There were about 400 that year, and it took me too long to figure out my responsibility to each one. It’s really hard to honor every book, and I think I was intimidated by the force of dreams coming at me like a big, wet wave. I know the excitement of finishing a writing project—big or small—and the intense hope that comes with sending it off. READ MORE >

Whas’Poppin: 6/27/14

This was a big week for Kim Kardashian, who recently became my BFF in an iPhone game. It was also a big week for poetry because–like Dan Gilbert–poetry can’t stop won’t stop.

Don’t worry, I’m still here.

——-

I.

mouth mouth mouth

some words onto righthere rises eyed

from under full lift my arms hold

(this weight of you)

Alexis Pope, “(soured)” (Leveler)

II.

I heard the mothers

call me trash. Beyond

me lay some other

me: a supine body

in the summer heat.

Caylin Capra-Thomas, “The Mine Fire Speaks” (Boiler)

III.

My greatest flaw is that I’ve granted my future-self permission to question myself at any time.

Michelle Dove, from “Alt Vices” (ILK)

IV.

Jon tells me

about a girl

who wants

to put her hair

inside his

belly button.

It’s a thing

Rob MacDonald, “Fetal Position” (interrupture)

V.

I want to teach this song

to the children we won’t make.

Ruth Awad, “Shame, Abridged” (Diode)

I HAVE TO TELL YOU by Victoria Hetherington

I HAVE TO TELL YOU

I HAVE TO TELL YOU

by Victoria Hetherington

0s&1s, June 2014

151 pages / $6 Electronic. Buy from 0s&1s

There’s a questionably selected excerpt from Victoria Hetherington’s I Have to Tell You available as a preview. It’s from the point of view of a college woman sitting around smoking weed with friends. Written with great veracity, this is as interesting as being the sober listener of a high college student retelling in detail her conversations (not very). Only when the excerpt culminates in the woman’s reflections—

—is the writing characteristic of Hetherington’s excellent first novel as whole: graceful and poignant, often redolent of Annie Dillard’s sparing prose rising to beautiful abstractions, open to the everyday’s influence on personal narratives.

I Have to Tell You is a catalog of pain splintered into multiple characters’ points of view in chronological episodes. Their story is told predominantly through first-person narration, but also through shorthand journal entries, emails, and google searches. It is a litany of voices trying to understand and rationalize their pain to themselves. Some may be put off by this agonizing, but it is not facile, solipsistic, or ironic agonizing—it is instead Socratic, a desperate dialogue with hurt, loss, impending death, and the social devaluation of aging. But all this pain talk is not to say Hetherington isn’t funny or clever, which she often is; writing about pain in fiction often benefits from humor, especially when it’s the pain of white middle-class Torontonians.

Hetherington’s characters indulge in their suffering, which becomes an act of resistance to what creates suffering. Cocaine abuse, erotic desire incommensurable with politics or friendship, an aging woman who gets plastic surgery because she sees in her own reflection the face an acquaintance makes at the moment of death; these self-destructions are resistances, announcements of the pain that goes hand-in-hand with living fully in the world. Their experience of misery is reminiscent of an old saying of Chinese criminals about to be put to death: “In twenty years I will be another stout young fellow”. It’s a proud act that challenges suffering by embracing it scornfully, acknowledging its cyclical pervasiveness.

Suffering in I Have to Tell You also recalls the Western biblical mythos surrounding gender and reproductive organs. Menstruation as God’s punishment is the biblical explanation of a biological phenomenon present before the Bible. Circumcision is a covenant God makes with men in order to arrange for divine dominance of their reproduction. One is an explanation. The other is a prescription. Here, women are punished simply by existing and must find meaning in light of this. Men are made to suffer (or subscribe to suffering) in the name of meaning, for some supposed higher and vaunted power. Similarly, men in I Have to Tell You see their suffering as a cosmic agreement in order to secure some noble identity. This is the case for a character who ascetically and sentimentally makes the woods his home as he prepares for death. Conversely, women are made to suffer merely by existing; they seek a way of explaining and living within the pain from which, being that of culture and stemming as far back as childhood trauma (as in one character’s teenage “relationship” with a strange abusive older man), they cannot escape but can perhaps revolt against. This is not to say the book has an uncomplicated rift between how different people experience pain; everyone, of course, experiences pain and everyone experiences it differently. But the distinctions Hetherington draws between the attitude and culture that surrounds male and female pain in I Have to Tell You, even the self-proclaimed feminist men (who, we see through one character’s specious arguments, still just don’t “get it”), rings true.

Despite their shortcomings, Hetherington respects her characters with an unassuming commitment to unironic truthfulness, showing great proficiency for writing in different voices that speak through a variety of media, woven together with beauty and coherence. The inclusions of technology lack clumsiness or forced cleverness; it’s an organic outgrowth of her characters’ natural assertions or understandings of identity. If there ever is a “Great American Novel” (a probably stupid concept) this is how it should look—but of course it’s Canadian.

***

Joe Hogle lives in Pittsburgh, PA. He is also known as poopsmithey, Ronny Cammareri, and ~LEATHA WHIP~. You can read a hypertext story and some of his poetry here.

June 27th, 2014 / 10:00 am

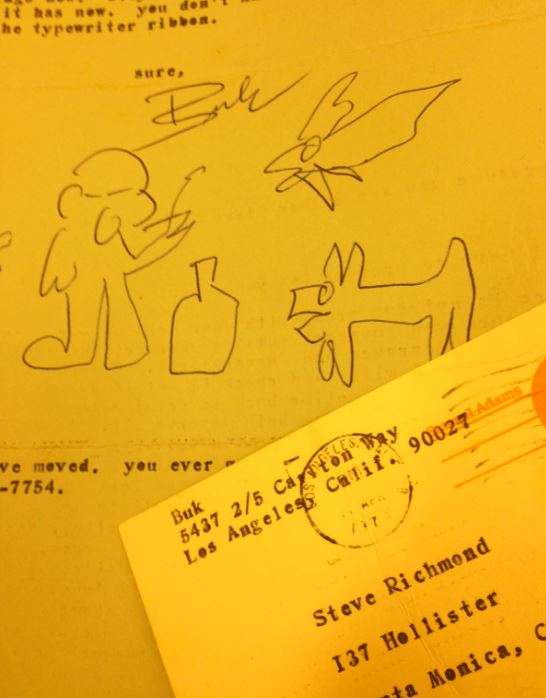

Buk–Everytime

I talk to you on the phone you tell me I’m a great

writer

and everytime I read you in print you’re putting me down.

What is it with you?

the knifer

I presume you are either Steve Richmond or Harold Norse.

I’ll have to presume it’s you, Steven.

there is nothing wrong with your writing—Or Norse’s.

it’s when you guys get outside your writing that you

often get depraved and nonsensical. I don’t want to

say it, but I will, and check it out if you please.

I asked Martin sometime back to print both you and

Norse feeling that you both deserved it. I have backed

both your and N’s writing—in forwards (forewords) to

your books and even by word of mouth over a bottle of

beer. and I don’t do it out of good feelings or comradie,

I do it because I believe in the artistry of your work.

then Norse attacks me in print (indirectly), asserting

that I have come between him and Sparrow, ruined his

chances when I have done just the opposite. I am not

out to get anybody; you guys are ridiculous. stick to

the facts. and on those 300 poems you showed me that

night, babe, since you hardharp it so much—most of them

did happen to be bad. all right, I’ve written some bad

ones too, plenty of them. we run into slumps of spirit

and life…now, do you understand? I say you’re

a very fine writer but you’re too jumpy about movements

in the fog. relax. I defended your work against a

certain guy you know quite well who said you couldn’t

write. (over)

HE CAME BY A WEEK AGO

I told him that I thought you were one of the most

powerful and original writers alive. I don’t want

to tell you these things but you fore ce me to. now

if you’ll get your head on straight and get into

doing the WORK you’re capable of instead of imagining

I wish your beath death, then we’ll both feel one hell

of a lot better.

I hope you’re getting some good ass and some love

and that the lines are falling into place. I’ve come

off a couple bad days drinking but am back to getting

all things now. stay with it. Some day it will come to

you it has now. you don’t know it. get your teeth

into the typewriter ribbon.

Sure,

BUK

p.s. I’ve moved. you ever got any need to phone, o.k., it’s 661-7754.

25 Points: Black Cloud

|

Black Cloud

by Juliet Escoria

Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2014

144 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. Juliet Escoria, as a writer, is like a birthday present you didn’t expect to get but secretly hoped you would.

2. It’s hard to pick a “favorite” from Black Cloud—but my top three would probably be “Heroin Story”, “Reduction”, and “I Do Not Question It”.

3. I feel like I know all of Escoria’s characters. I empathize with them. I care about them. I want to fuck up all the shit that made them miserable because, to me, they deserve better.

4. There are stories within these stories—little hints into the lives of these characters that stick with you.

5. Playlist for this book: Gary Jules’ version of “Mad World” on repeat.

6. Feel like Escoria is a new-age Bukowski but is extremely new and original at the same time.

7. These stories seem so real that I can’t decide if Escoria actually lived through all this or not. (Probably took experiences from her own life to build around these stories—that’s obvious—but I’m more so troubled with the idea that her life has been that awful thus far.)

8. Declaration: Black Cloud is the best work produced by a new, young writer this year and I challenge anyone to top it. (Spoilers: you won’t.)

9. Black Cloud makes you realize how good your life is.

10. Sadly, a lot of Generation Y can relate to the absence of fathers in this story collection.

June 26th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

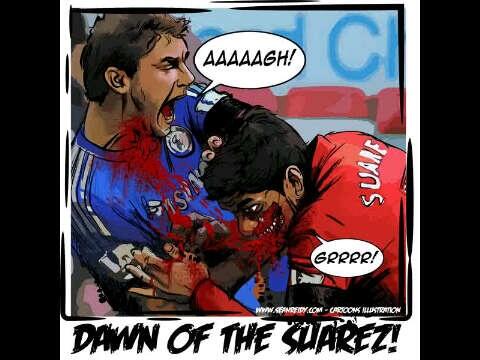

Biting is despicable, of course.

But how many writers, in the throes of creation, wrastling that dark angel, have resorted to biting?? Have chomped down on the Muse’s neck or shoulder??

Or perhaps the Muse is the biter, spurring us on to inspired action?????

(and, note: it’s ok to be a Creative First Responder in a World Cup biting incident. But not in a shooting tragedy. . . . . .O, where do we draw the line ??? . . . . O, poor Luis… O, poor Seth)

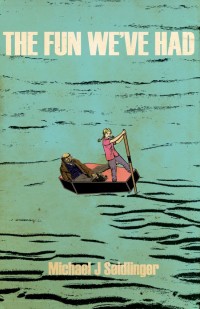

The Fun We’ve Had

|

The Fun We’ve Had

by Michael J. Seidlinger

Lazy Fascist Press, 2014

168 pages / $11.95 buy from Amazon

Rating: 7.9

|

How do you write a thrilling and entrancing Alt Lit novel?

Start with a chorus of disembodied voices telling us that “the waves are helloes; the incoming storm the sincerest goodbye. Like every single one of us, they are holding on. We held on until we could no longer hide. No one can hide out at sea.”

June 24th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Colum McCann — Transatlantic

……….what was Colum McCann, National Book Award Winner, thinking when he posed for this author pic ??

“I am profound. I am sooooo profound.” — ??

“This is sure gonna sell a lot of copies!!!” — ???

“I have been translated into 35 languages!!” —??

“What would James Joyce say about this???” — ?

“Is this really a good idea??” —- ????

“The scarf’s the clincher!!” —- ????

______________________________ ???????