Eating Yourself to L()ve: A Review of Autophagiography

|

Autophagiography

by A & N

gnOme, 2014

192 pages / $12.00 buy from Amazon

Rating: 8.5

|

Autophagiography, the latest release from the small pseudonymous press Gnome Books, is a documentary epistolary ‘novel’ composed of temporally-congruent email and twitter messages between two persons, followed by a short treatise which defines and theorizes some guiding principles for the weird ‘saintly’ love/friendship at the center of the story. In form and content, the book is one-of-a-kind and hard to describe. Here are some salient features:

Language/Style: the protagonists communicate in a kind of poetically inspired intellectual style that is both sublime and ridiculous. For example, “Dear One by Whom We Orient Ourselves to Ever Greater Bewilderment” (8), or, “Your words make me blush in my tomb! Idiorrythmia freaks, torment chewers, self-eating love-worms…” (92). It is difficult to imagine people actually writing to each other like this and at the same time obvious that none of it is made up. At its best, the text effortlessly spins out stormy passages of living prose-verse worthy of Lispector and Bataille (both of whom are referenced as sources of inspiration). At its worst, it repetitively babbles with baroque terms of endearment perhaps better to have been left on the cutting room floor—though to have done so would have been impossible. Overall the idiosyncratic and spontaneous authenticity of the whole thing only accentuates its mysterious hyper-fictionality, haunting the work with the sense that the writers may indeed be flirting with madness, or better, hallucinating themselves out of existence: “Love is not for this life and yet it is precisely here that it is happening” (70).

Ideas/Themes: As the clever one-word title indicates, the book records and enacts a process of autobiographical self-eating that attains and/or strives for a kind of sanctity. The (non)relationship is platonically romantic: “This is not a ‘relationship’. This is love itself (in world and not of it). But how we relate!” (72); “This is not to say that what happened is not miraculous! … Why? How? All the more that we were never alone!” (102). It also involves a number of interesting mystical dreams or visions: “Something unlike I have ever experienced really happened within me and to the whole world at the same time. No way to explain, but it was like swallowing the infinite auto-recursive spiral all the way, like eating one’s head and exiting stunningly unharmed into an other side which is more this one than this” (178). Whether or not the authors actually become saints is a silly question that the text nevertheless makes one ponder the meaning of. The reader may just as easily feel sorry for them or wonder why they do not just run off together. In the end this reviewer was left happily swimming in a peaceful existential desperation reminiscent of E. M. Cioran’s Tears and Saints (a text mentioned several times), where the divine truth of sanctity is as real as the unreality of the universe: “Can it be that God is only a delusion of the heart as the world is one of the mind?”

Identity/Authorship: This is a significant accidental experiment in documentary authorship, an ‘as-is’ book with several delightful surprises and contradictions. The formal interplay between-across email and twitter embodies the multi-channeled and erotically vexed nature of socially networked existence only to feed it back into the mouth of the book as the obvious and maybe only possible earthly offspring of spiritual friendship. Indeed the conception and editing of Autophagiography becomes an important part of the narrative itself, so that the text literally and narratively eats itself into its own real present, like some kind of monstrous love-child proverbially devouring the authors out of their inexistent sub-oceanic house and home: “The monster is here and I cannot stop it, I don’t want it ever to shut up. Whatever happens in this life there will be the fault of this cataclysmic now screaming to me, deafening me with the echo of a deformity that I always was” (73). At the same time, the book is imbued with its own palpably literal and melodramatic worldly reality. The communication-communion endures and reflects upon the difficulties it causes for the saints’ other true loves and also shamelessly relishes its own embarrassing confessional responsibility: “Not one syllable of our words would I alter, not one atom of our sigh, but from today forward, this new day of a new life, I must somehow address you more sanely, in words that proliferate and expand to befit more and more the purity of this intolerably sweet friendship, this little bond through which we are indeed becoming ‘as close to nothing as possible’” (129). The open secrecy of the work is accentuated by the discoverability of the authors’ worldly identities and their entrapment within a web of recent events and current interests (Lovecraft, Argento, Cioran, Thacker, Land, Lispector, Meillassoux, Negarestani).

In the live medium of its essential imperfections, Autophagiography is virtually-actually worse and better than this world, a worst best and best worst that would prove to open a way to paradise, if only if it were possible to read it properly. One can only hope without hope that its authors somehow find happiness in this sphere or the next, or at least in a weird new somewhere that is neither.

July 22nd, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Hardly Getting Over It: A Review of See a Little Light

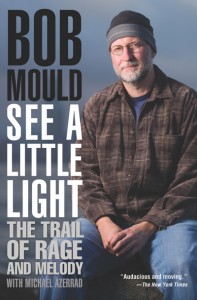

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

by Bob Mould with Michael Azerrad

Little, Brown and Company, June 2011

416 pages / $24.99 Buy from Amazon

Why would anyone expect the ex-member of a famous rock band—those fertile dens of back-stabbing, girlfriend stealing, passive-aggressiveness and all around hurt feelings—to offer a healthy recounting of his time in said band? It’s like asking a combat veteran to empathize with the people who shot at him.

Yet, for those rock artists we truly admire, we crave that kind retelling. They’ve blown our minds so many times in the past with their transcendent work. If we’re disappointed they can’t deal with their issues enough to tell their band’s story in a fully-realized way, it’s only because we’ve learned to expect that much from them.

I skipped reading Bob Mould’s autobiography See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody (Little, Brown) after hearing Mould was less than resolved about his time in the formative post punk band Hüsker Dü, and in particular with his relationship with drummer/songwriter Grant Hart. I was a big Hüsker fan in the eighties and nineties, and I’d identified closely with Mould’s rage on classic albums like Flip Your Wig, Zen Arcade and Warehouse: Songs and Stories. I’d fallen away from his work around the time of his last album as the frontman of the band Sugar, and steadily found myself less interested in him as the years passed. The singer was so associated with the blood-curdling screams he’d let loose during his Hüsker years, I preferred to think of him as conquering his fury, moving on to better things, getting over it. Yet here was Mould, supposedly getting thorny about Hart and bassist Greg Norton in book form. Not interested.

But those who skip See a Little Light for these reasons will miss much of a story that few but Mould can tell: of Hüsker’s beginnings and ascendency, of the nascent eighties hardcore subculture in America that would lay the groundwork for the massive grunge movement in the nineties, not to mention refreshingly candid insights into Mould himself, one of his generation’s most conflicted icons.

Mould didn’t get riddled with rage by happenstance. His upbringing in rural upstate New York with an alcoholic, abusive father was plenty turbulent, and discovering his homosexuality in adolescence only further alienated him from those he grew up with. Most harrowing to me was when Mould was eighteen and for the first time away at college in St. Paul, Minnesota, trying to find his place in a confusing world. Not only were they stringing up homosexuals like deer back in his hometown, but, Mould writes, “the weekly phone calls with my family were difficult enough, especially the ones where my father threatened to sever my financial support or escalate his violence toward my mother.” I can only imagine a young, scared Mould desperately needing to make urban Minnesota work for him, knowing he had no home to go back to.

July 21st, 2014 / 10:00 am

Green Lights by Kyle Muntz

Green Lights

Green Lights

by Kyle Muntz

Civil Coping Mechanisms, May 2014

108 pages / $13.95 Buy from Amazon

In Kyle Muntz’s Green Lights, we’re exposed to wavelengths as beams of prose, an unnamed narrator whose world is flooded in the disparate hues of existence. There’s a meditative quality throughout, a detachment borne of Kafkaesque inquiry and a yearning for communication that teeters on the fiat lux’s of every day creation. Not just through visible light, but the invisible nanometers that escape normal sight. “I want to talk about color,” the book begins, and the colors of the spectrum quickly become a metaphor for revelation and metamorphosis. The characters, from the moon turned into a woman, to an old man embodying evil, become symbolic accoutrements for the journey which turns out to be an excursion to another dimension. Elements of the fantastic shine as in the “Blue” chapter when the whole neighborhood is covered in noirish film shades that masquerade as night, and then, “The world froze… Ice had taken over the world.” Winter isn’t just the congealing of the veins and muscles, but a coat of futility wrapped around his routine actions. “After much effort, I thawed my room. I’m not proud of the things I did to accomplish this,” he confesses, then further reveals, “I got a job carrying a flamethrower around the neighborhood, melting people. My coworkers treated me like shit.” The frost of survival is just as bleak as the cold treatment of his colleagues and the blending of colors weaves the conflagration of pain with the inferno of transformation.

There’s a melodic beat to Muntz’s writing, terse descriptions of events interspersed with sudden bursts of graphic visuals, often macabre in its evocations. It’s a delicate balance, but one he masterfully navigates, exploiting minimalism to maximize emotional defibrillations, injecting the grotesque to animate the mundane:

“One time when I was walking in the darkness, I stumbled over something, and it was him, sprawled on the ground, unable to move. He didn’t have eyes anymore. Maggots crawled amidst the remnants of his skin, fibrous muscles like totted spaghetti. Worms fucked his intestines. Beetles were chewing his brains.”

Like signal lights, there’s a revolving flow of ideas that are given free rein and then brought to a halting stop, warning yellows demarcating the blurry boundaries between illusion and reality. That border is often where Muntz’s narrator lingers, rarely surprised by the absurdity of the surreal events that happen around him, instead, levitating past the barriers. It’s almost as though the green light were always on and physics broken free of limitations to innovate. Muntz revels in experimentation, relishes the opportunities to change up the traditional narrative as he bakes x-rays of playful contemplations into the atlas of his construction:

“Sometimes when I looked into the distance, I remembered that the darkness I could see there was actually the mountain, holding up the base of the universe. If I were to walk that way, the neighborhood would never end, but eventually it would become less real… The road continued even where the world began to change colors.”

His main companion is his love interest, E, who is as curious as the narrator about the frontier, a geography that challenges the intellectual as much as the physical. Both are intertwined and both affect each other, a symbiotic terraforming that is volcanic in its effect.

“Nearby, behind an abandoned house, we found an immense flower growing from the ground. The flower was at least a hundred feet tall. Beads of water clung to its sides… She nodded. ‘It looks like a picture of itself, meaning it looks better than real. That means something. It implies amazingness.’

‘Should we climb it?’

‘Probably,’ she said. ‘If we didn’t, we would feel bad about it later.’”

There’s a lot of climbing in Green Lights and like E, we know we’d feel bad if we didn’t venture upward. Along the way, we get dashes of the videogame classic, Earthbound, embedded with David Lynch, Borges, and doses of Marquez. The combination acts as a variety of hues to assault our senses in this quirky and likable hike while at the same time, Muntz weaves his own identity through the narrative. I just wish there were more colors in the spectrum.

***

Peter Tieryas Liu is the author of Bald New World and Watering Heaven. He entropies at entropymag.org. He loves green lights. And red ones. And blue ones too.

July 21st, 2014 / 10:00 am

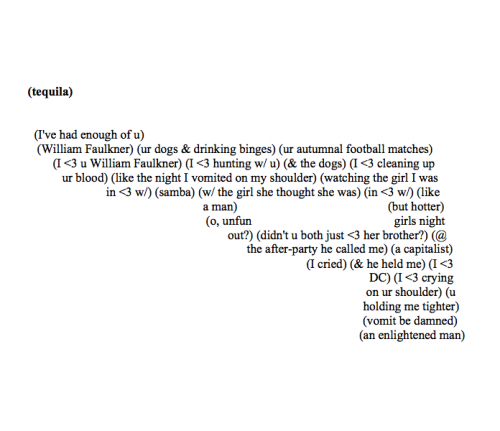

Montana Ray

Bio: Montana Ray is a feminist writer, translator, and mom to Amadeus who is five. In 2015, Argos Books will publish the first full-length collection of her concrete poetry, (guns & butter).

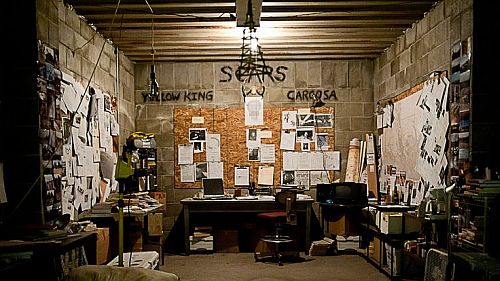

Gary J. Shipley on True Detective, Cosmic Pessimism, Etc, Etc

So, I’ve been quite preoccupied with this great essay on True Detective by Gary J Shipley which can be found at Bright Lights Film Journal. The essay, it turns out, is a wonderful, thorough and haunting meditation on the (trapped, locked-room) human condition, conciousness, pessimism, etc, etc:

Cosmic pessimism is the refuge of the pessimist who still finds himself alive, the refuge of a futility he has not made his, the refuge of the mystery of his not knowing and the vanity of trying, and he finds claiming this impossibility, the externally codified nature of his predicament, to be less taxing than any weariness of knowing. For to remain is not to make the world and its secrets yours via the self you have first established as other, but rather to make the self the potential agent of its own redemptive ignorance via the otherness of what’s outside it. Hart diagnoses this condition in Cohle, tells him his denial lies in being “incapable of admitting doubt,” and so articulates how salvation lies not in the flimsy panoply of faith but in acknowledgment of what is not known, for Hart like Cioran knows that “doubt is less intense, less consuming, than despair.” And while, as Eugene Thacker explains, horror and our philosophical interest in the world around us may well be intertwined, both being concerned with “the paradoxical thought of the unthinkable, in so far as it deals with this limit of thought, [ … and] in so far as it evokes the world-without-us as a limit,” pessimism somewhat counter-intuitively becomes the antidote to this horror, and cosmic pessimism the antidote to Lovecraftian/Thackerian cosmic horror: in the case of the pessimist the horror of unthinkability is transformed into a salve, a place of solace for thinking that cannot escape itself, a perspective smeared with the excrement of that which being must always become.

again, to read the full essay click here

July 18th, 2014 / 4:00 pm

Andrew Duncan Worthington Interview

Tamped-down rage never quite enunciated hums quietly beneath the surface of Andrew Duncan Worthington’s debut novel Walls, a new release from Civil Coping Mechanisms. Narrated by a twenty-something Ohioan, Walls strings together banal humiliations, flat-footed conversation, shitty jobs, and shittier sex to create a convincing tableau of millennials marooned in boredom. Worthington is also a founding editor of Keep This Bag Away From Children. Recently, we talked shop over G-Chat because we were both born after 1980.

—-

Tracy O’Neill: You begin Walls with a lengthy history of a failed building project. We find out by page three that this description is spoken by a tour bus guide. In some ways do you see the novel as a tour of a failed project, and if so, what is the failed project?

Andrew Worthington: I hadn’t really thought of that, in terms of the novel being a tour of a “failed project.” I did want “Ohio” or “northeast Ohio” to be a character, in a way, though, in the sense of it being ever-present almost as much as the main character. The main character as a failed project? I don’t know. But that character of “Ohio” is a failed project. It’s not its fault, though. It was just a body of land that people moved to because they couldn’t have enough land somewhere else. Ohio embodies, for me, the most extreme but also the most mundane aspects of what is wrong with the United States. I’m getting off your point, I think. Maybe if you told me what you mean or think, that would be easier.

TO: What do you think is wrong with the United States?

Contrapposto Action Queen by Connie Scozzaro

Contrapposto Action Queen

Contrapposto Action Queen

by Connie Scozzaro

Bad Press, 2013

$9 / Buy from Bad Press

Before I’d ordered the book, I listened to Scozzaro read “What Is Parents?” on the Claudius App and fell in love with the poem. I listened to it the way an eight year old listens to Beatles’ songs. I’d drag my partner in to listen to it and tried to dub the poem to a mix tape but it didn’t survive the transfer. “Isn’t this just the best?” I’d say, jumping up and down as Scozzaro read in a brave and insistent voice.

“What Is Parents?” is one of the more elegant ones. Her verses make adept shifts from a naïve diction to classy Rimbaud/Swinburne-esque lyricism. I like the tension between the vague, the true, and the fantastic in “What Is Parents?”

After this good work with something not mine,

I come home to you, we feed each other and laugh. I love you,

especially when we fuck really well, but probably

we fuck really well because I love you so much.

In the heart of the grass, a fountain rushes,

blood in the shape of a rose. For seconds

I understand birth, and the Incredible String Band

play their instruments

well. What is parents?

What are dreams?

These poems, and this poem, consider everyday ritual and material limitation, but also seem to mediate banal domestic desperation through an intensely personal kind of verse. In my reading, I like to think that the poems are able to capture the boundary between boredom and fetishization.

Contrapposto Action Queen is eight longish poems long. These poems are exhausting in the best way. Reading them I’m too full of ideas. The collection is so full of colliding images, unresolvable emotional states, and shifts in diction. Scozzaro is very good at eloquent and cool verse that isn’t afraid to betray itself with urgent brattyness. Her poems are exciting because they seem to constantly shift, from image to image, from the exact to the vague, as they unfold. From “Elena, Whatever: You Are But Dreaming”

Suitors buy her roses, or posies, which upon inspection,

are but mauve, petals trembling pools,

obscuring heaving shoulders on ahead.

Two or three swoon from daily collapse, this way and

that, to be in another world, to know

how to use your hands.Write what pleases you, what displeases me,

black liver wobbles out the drain,

dragging itself on a few gross legs.

You are the hero of the bathroom mould,

blocked drain, streams of tangled hair,

you squirt, we get deposit back.

July 18th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Eternity by the Stars: An Astronomical Hypothesis

Eternity by the Stars: An Astronomical Hypothesis

Eternity by the Stars: An Astronomical Hypothesis

by Louis-Auguste Blanqui

Translated by Frank Chouraqui

Contra Mundum Press

202 pages / $20 Buy from Amazon or Contra Mundum

Eternity is a concept rather dubiously tough to wrap the mind around. Throw in the idea of duplicate worlds and simultaneous events with differing end results, replicating yet infinitely fracturing the day-to-day reality we recognize as “the real,” and the average reader’s head begins to spin. While these matters are not always tidily handled within Louis-Auguste Blanqui’s Eternity by the Stars they are dealt with utilizing a fair amount of pith.

Blanqui after all was a ubiquitously engaged nineteenth century French revolutionary thinker and “man of action” who wrote this book from May to November of 1871 while under constant threat of armed guard in a heavily fortified jail on a small, rocky island just off the coast of Morlaix where waters of the English Channel mix with the Atlantic Ocean.

Translator Frank Chouraqui’s introduction provides orientation concerning the biographical details behind Blanqui’s work while also marvelously untangling some of the thornier scientific scenarios presented in his argument. There are two key scientific authors whose work and ideas Blanqui cites, often contentiously: Pierre-Simon Laplace and Francois Arago. Chouraqui irons out the creases in Blanqui’s presentation of each author’s argument in relation to his own.

The science passages in Blanqui’s text are among the most challenging material for unfamiliar readers. Having Chouraqui’s lengthy introduction to refer back to along with the endnotes he provides to the text are of enormous assistance, as is his extrapolation upon the clear relevance of Blanqui’s writing to the work of Walter Benjamin, Jorge Luis Borges, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

In and out of trouble with French authorities most of his adult life, Blanqui fought his way through numerous ups and downs accompanying several frequent changeovers within the government throughout his lifetime. These were a series of political changeovers which both in his writings and actions he did his best to ferment. Imprisoned inside Fort du Taureau (Castle of the Bull) Blanqui conceived of and wrote Eternity by the Stars while awaiting his trial, insisting that the text was an integral part of his defense.

Chouraqui describes how, locked up in the island prison, “Blanqui found himself surrounded by a world of repetition.” Confronted by such a situation, Blanqui laid out an argument for the prevailing destiny of everything in the universe that would serve to counter the frustration he felt, as Chouraqui describes it: “The main claim of Eternity by the Stars is that the discrepancy between a limited — albeit great — number of possible events and the infinity of time and space necessitate the infinite repetition of all possible events.”

July 18th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Juliet Escoria & Scott McClanahan’s Honeymoon Tour Diary (Part 1)

SUNDAY, JULY 6

SAN DIEGO TO LAS VEGAS

SONG OF THE DAY: ELVIS PRESLEY “I CAN’T HELP FALLING IN LOVE”

JULIET: We packed up my stuff in the car, said goodbye to my family, and were on the road by 2pm. We stopped for food and gas in Elsinore. I decided that it would be a good idea to buy a pack of cigarettes (I quit smoking in November and haven’t had a cigarette since) and smoke one for every state we went through, in order to “celebrate our honeymoon.” As we drove, we listened to the mixes we made for our wedding. Most of the drive involved us discussing funny moments from the wedding. EXAMPLE: My dad apologized to Kendra Grant Malone for being so drunk. Kendra told him not to worry about it. My dad responded, “Power to the people.”

At some point, things took a turn for the worse. We passed the word “Calico” all big on the side of a mountain, which I’m not sure is a town or a street or a gang, but the conversation shifted to all the calico kitties pushing those rocks together with their paws. New characters were invented, such as Man Who Thinks It’s Still 1989 Politically and Woman Who Becomes Belligerent When She Sees Red Honda Accords.

Plate of stick-shaped items from buffet

We arrived in Vegas around 8pm. Our hotel room featured two bathrooms, a Jacuzzi bathtub, a shower with three showerheads, a fireplace, a dishwasher, etc. Everything was modern and sleek looking, to the point that the room felt vaguely terrifying and everything was difficult to use. I went on the computer to find a good buffet for Scott and me to eat at, because we had decided we wanted to eat until we felt sick. I found two ones that looked really good but that would have required us to walk so we ended up deciding to eat at the buffet at our hotel even though it had bad reviews on Yelp. The buffet was, as expected, mediocre. I ate one oyster anyway, even though I was afraid it would give me food poisoning (it didn’t). Scott drank five Diet Cokes.

We took a short walk afterward in order to feel slightly less fat, but didn’t get very far because it looked like it might start pouring rain (it didn’t). On the way back, we saw a very tall but handsome foreign guy walking arm-in-arm with two prostitutes. We discussed the nature of prostitution, and how it differed from stripping. It was concluded that prostitution was more honest and therefore in some ways more honorable. Scott seemed to know a lot about prostitutes, which troubled me.

At the hotel, I took a bath in the Jacuzzi bathtub. The tub was very large and oddly shaped and it made me feel like a lobster. I enjoyed the bath, and my lobsterness.

Juliet’s lobster bath

SCOTT: Yep.