Leaving the Sea

Leaving the Sea

by Ben Marcus

Knopf, January 2014

288 pages / $25.95 Buy from Amazon

“I’d been thinking for years about language as a toxic substance,” said Ben Marcus in a 2011 interview with HTML Giant. “Language itself making people sick. Speech and text, all of it poisonous.”

He continued, “I seem to write about language a lot. Language as a physical substance with deviant powers: a powder, a drug, a wind, a medicine. I can’t really help it.”

Ben Marcus is obsessed with language on a sort of sadomasochistic bent. Consider this invective: “In English, no matter what you said, you sounded like a coddled human mascot with a giant head asking to have his wiener petted…”

And, “English, in which every word was a spoiled complaint, a bit of pouting…”

And, “…a whiner’s tongue.”

And, “At least overseas he didn’t speak much English.”

And, “….he spat his useless English.”

All of these are taken from Leaving the Sea, the new collection of short stories from Marcus, who is bound and determined as ever to make us sick with language. Leaving the Sea is divided into six sections on loose formal and philosophical grounds, and in loose order of obscurity and opacity.

The collection begins safely, with Marcus’s most accessible work, although there isn’t much in the way of traditional resolution even here. The key to any good relationship, the writer/reader one included, is a managing of expectations, and nowhere in even his most outwardly inviting writing does Marcus hint at anything that suggests closure and a case of the warm-and-fuzzies.

Another consistency: Marcus’s characters are consistently on the wrong side of power balances, often for reasons unclear. The opening story, “What Have You Done?” features a protagonist who has returned “home” for a family reunion of sorts, only be shunned and vilified by a family that seems equally bemused by and afraid of him. We see hints of an “old Paul” boiling over throughout the story, but the title of the story remains a taunt, as we never quite find out what Paul did. (To consider this a spoiler, by the way, is to miss the point of Marcus’s writing, which can be very much like tantric sex sans orgasm. I mean that in a good way.)

The characters we meet in Leaving the Sea are often achingly sad, borderline alexithymic, and resigned to a fate over which they have no control. Despite the harsh sense of determinism, Marcus’s characters all seem to feebly make attempts to control what little they can. Fleming in “I Can Say Many Nice Things” is a serious writer forced to lead a creative writing seminar aboard a cruise ship for financial reasons while trying to resist the temptation of an affair with an enthusiastic student as a small act of mitigation against his bitter wife back home.

In “The Dark Arts”, Julian fends off nighttime invaders in a Düsseldorf hostel while undergoing experimental treatments for a rare immune disease — an “allergy to my own blood”, he calls it — all the while waiting for his girlfriend, who has yet to arrive from France after a lover’s quarrel. When she does materialize, cold and aloof, we’re left wondering if Julian might have been better alone, a thought not lost on him. “Had anyone,” Julian wonders at one point, “ever studied the biology of being seen? The ravaging, the way it literally burned when you fetched up in someone’s sight line and they took aim at you with their minds?”

If it is a subterranean discomfort the reader feels in the first three stories, the last of Part One, “Rollingwood,” carries it to full nausea. Mather is the father of a sickly child, afalter in every aspect of life, and seemingly unable to summon the strength to fight back against an ex-wife and a potentate boss who appear supercilious towards his continued being, particularly when his usefulness runs out. What transpires leaves the reader feeling gutted, somehow disappointed to the point of sickness, although one could hardly call it a visceral story. The language is plain, inviting even, but weighted with sadness.

Part Two consists of a series of interviews with a series of cultural tastemakers/gurus who believe they hold the key to a happier life by way of shunning the adult world. One, in a not-so-subtle allusion, believes that perhaps we’d all be better off in a cave, though this one has no light by which to project any shadows at all.

Parents — and more specifically, the child’s Stockholm-syndrome-like sense of duty towards them — dominate Part Three, which is comprised of two stories. The first is a meditative essay by a man who wonders for the length of the story how his actions or inactions might hasten or delay the death of his mother. The story is rife with a sort of realistic morbidity, particularly in the passages that describe different scenarios in which the mother’s body might be found, and after how long. The second story of Part Three, “The Loyalty Protocol”, takes place in another of Marcus’s miasmatic hinterlands between our world and a bleak alternate reality. During a series of drills for an unspecified threat, Eddie must choose whether or not to break rank and bring his senescent parents along, who have not been called to the rendezvous point.

Part Four is comprised of a single story, “The Father Costume”, which is particularly unsettling in not only its bizarre, arcane imagery, but in its ever-shifting set of linguistic paradigms, with characters all seeming to speak a different language and there being no real common phrasing to latch on to, ensuring the reader never has a complete grasp on the world Marcus has created. (The story, it should be noted, would appear to be a reworking of a 2002 book of the same title by Marcus and fellow author Matthew Ritchie.)

It’s often hard for a reader to determine whether a writer is challenging them, or just fucking with them, and the queasy feeling one gets through this story makes it either one to deep read or skip altogether, depending on your predilections as a reader. All the same, it seems like just the sort of story Marcus had in mind when he said, in the same interview:

“In the end I want to write things that I don’t know how to write, because this seems to command the most energy and desire and attention from me. It makes me sort of sick with anxiety. When I’m uncomfortable and confused and curious I tend to try much harder to figure things out.”

The language games continue in Part Five with a set of stories that seem aimed at putting the mundane into new dialectical contexts. “First Love” is a stumbling attempt by a nameless narrator to frame his amorous attempts in a language we might understand, even taking the time to tell us, “The word body used to refer to the evidence left behind that someone has died.” As with many of his stories, Marcus refuses to tell us whether the “used to” here implies a futuristic world, or merely the shattering of an individuals that renders language, at least in the objective sense, largely moot, a la Kate in Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress. Each story of this section poses that same question, as family life and relationships and lovemaking are all forced through the cracked lens of Marcus’s devising.

READ MORE >

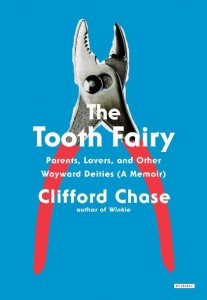

The Tooth Fairy: Parents, Lovers, and Other Wayward Deities (A Memoir)

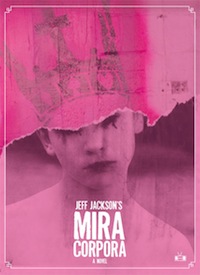

The Tooth Fairy: Parents, Lovers, and Other Wayward Deities (A Memoir)  Mira Corpora

Mira Corpora

Leaving the Sea

Leaving the Sea Savage 1986-2011

Savage 1986-2011 1914: A Novel

1914: A Novel

*Tammy is a print publication that features poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and criticism from the esteemed fringes and unguarded egresses of American letters, international writing in translation, and forms of visual art and poetics that lend themselves to the printed page. The third issue

*Tammy is a print publication that features poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and criticism from the esteemed fringes and unguarded egresses of American letters, international writing in translation, and forms of visual art and poetics that lend themselves to the printed page. The third issue

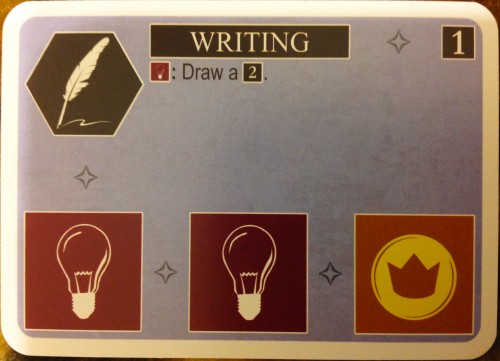

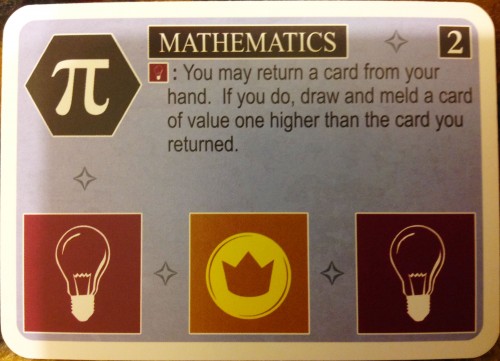

Innovation

Innovation