An Interview with Alissa Nutting

Alissa Nutting is the author of Tampa, a novel, and Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls, a collection of short stories. Both are spectacular. Today, Alissa had a conversation with me about her new novel, how it was written, how it has been received so far, and the weird, scary, ugly mess that is American sexuality. It was great: you can and maybe should watch it. But regardless, you should buy and read her books.

Paul Dean plays the Spelunky daily challenge while discussing Kurt Vonnegut, chocolate cookies.

An Interview with Roy Kesey

Roy Kesey, whose most recent book is the collection of short stories Any Deadly Thing, recently spent some time talking with me about his writing. Kesey is also the author of Pacazo, one of my favorite novels of 2011, All Over, another collection, and Nothing in the World, a beautiful novella.

I suggest listening to/watching this thing up to the 40:30 point, at which point I would rather you closed the tab and forgot all about it. Our connection died at this point, but what it looked like from my perspective was Roy staring at me in utter bewilderment for several minutes straight, which was kind of awkward. I would edit it out and put a proper ending on it if i could! But I can’t.

Regardless, Roy says some very smart, useful stuff, and I had a great time talking to him. You should buy all his books.

Interview with Lindsay Hunter

Lindsay Hunter, author of the brilliant and beautiful collection Don’t Kiss Me (buy it here, or, you know, wherever) was kind enough to talk with me about the book and her writing generally. We did it over Google’s hangout software, which apparently mirrors your own image as you’re chatting, which led me to believe that the book would be flipped horizontally when I showed it to you, the viewer. So that’s what that’s about. I’m also super awkward in real time, so that’s what that’s about. I hope Lindsay enjoyed the conversation, and I hope you will find and read her awesome book.

Normally I suggest just plugging in the headphones for these, as they are not designed to be visual feasts, but Lindsay does some incredible camera work, and we get to meet both her dog and dog walker. So that’s something worth seeing.

An Interview with the Creators of Starseed Pilgrim

Yesterday, after my lunch but before theirs, I interviewed Droqen (i.e., Alexander Martin) and Ryan Roth, the developer and sound designer of Starseed Pilgrim, a beautiful, mysterious game about “tending a symphonic garden, exploring space, and embracing fate.” It’s six dollars and I am extremely confident your computer can run it. I was kind of awkward and shy, predictably, but the two of them did great. We did it as a video because that was expedient, but if I were you I would treat it like a podcast — listen to the audio; don’t feel like you’ve got to watch. We talked mostly about video games — Starseed Pilgrim, Droqen’s other games, stuff we had all played and enjoyed, and things we didn’t like so much. But I don’t think you have to like video games very much to find a lot of what they said interesting. I made some annotations (indexed by time code) to provide context and further information for the things we discussed; click past the fold to see them. READ MORE >

Dear Everyone

This is a post about Seth Oelbaum, and I wish that it wasn’t.

I got my copy of the keys to this blog while I was unemployed. I had just quit a job not because I hated it, and not because I didn’t like the people there, but because I wasn’t very good at it. This was hard for me because I am the sort of person who needs to believe he is the best at basically everything. I am a teacher’s pet, a perfectionist, a people-pleaser, a needy pile of nerves, sometimes. The way I started writing here is this: I had written at the blog for my magazine for a while, and some people here had liked some of the posts. Roxane Gay was one of those people. She told me she had suggested to Blake Butler that I be invited to post here. Blake seemed receptive, but nothing happened, and meanwhile I was looking for work but not finding any and I spent most of the day sitting on my couch reading job listings and feeling my heart hurt. I needed to feel like I was succeeding in something. I thought that one way I could feel like I was succeeding would be to write for this blog, which had been a comfort to me in grad school, where two different instructors made me openly cry by telling me that I was no good at fiction. I liked to tell myself that the sort of people who read this blog would like what I was writing, and in fact had liked it in the past, as evidenced by certain posts and discussions, and that there were a lot of people who read this blog, and so I couldn’t be all bad. Now, unemployed, heart aching, I thought that writing things here might help me feel better again, and that it might advance my writing career in some way, which is important to me, because of said personality defects. So I sent Blake a gchat and asked him if I could please start writing here. I think I e-mailed him about it too. He said yes. And so I did.

So for a while I posted a lot, and I watched my posts closely to see how they did in terms of traffic and comments, especially as compared to other posts by other, more popular writers, to the extent that the WordPress back end would let me discern that. It made me feel productive. My heart hurt a little less.

My posting slowed to a trickle when I found new (and very stressful) work. I also had a super-long novel to finish, and a story in Best American Short Stories, which made me feel that I needed to do other things (like finish said super-long novel) in order to capitalize on this success, for the sake of the aforementioned writing career. For a while, I didn’t read this blog, except very occasionally when I saw that A D Jameson had written something especially geeky, which is basically my jam. When I started reading again, I saw that Seth Oelbaum was posting with some regularity. And that made me want to never write here again. It made me want to stay away. READ MORE >

Dear Narrative Magazine: Please Die in a Fire (Also, Kindly Remove Me from Your Mailing List)

Dear Narrative Magazine,

Recently, I began to receive e-mails promoting your publication, in spite of the fact that I have never in any way expressed interest in you or what you do. I have never submitted to your magazine (because you are clearly a scam operation) and I have never given you any reason to believe I might do so in the future. I have never read anything in your pages, because I detest you. There is simply no ethical means by which you could have obtained my e-mail.

When you began sending me spam, I attempted to unsubscribe from your mailing list. I spoke to other writers who hold you in similar disregard, and they said that they had been trying to unsubscribe from your mailing list for months, and that it was impossible. You wouldn’t leave them alone. I sent you several hateful tweets (because I hate you). I unsubscribed again just to make sure. Maybe I unsubscribed a third time? I don’t remember.

Today I received another spam e-mail from you. I do not admire your tenacity. You are pond scum. I can ignore this fact when you aren’t spamming me but I can’t when you are. My e-mail address is mike(d0t)meginnis(at)gmail(dot)com. Take it off your mailing list immediately. (I mean it. This is not optional. You are going to do this now.)

I invite anyone else who would like Narrative Magazine to stop e-mailing them to post about it in the comments. (Dear Narrative: These other e-mails won’t be optional either.)

With All My Contempt,

Mike Meginnis.

When people use social media to promote their books, that is their way of saying that they can’t be bothered to figure out how to actually promote their books. When people tell you to use Facebook to promote your book, what they are doing is giving you a way to keep very busy while no one at all reads you.

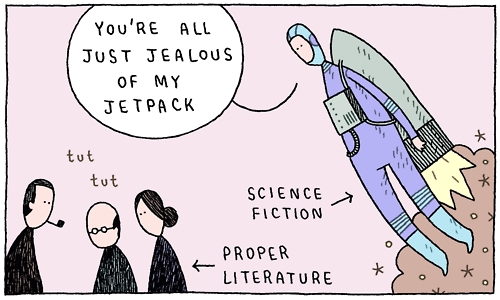

Arthur Krystal and Everyone’s Favorite Genre Fiction Fallacy

It seems perhaps in poor taste to post today with all of Sandy’s madness, but the way people talk about genre fiction and literary fiction has long been a sore subject for me. In graduate school (though not in my undergraduate program, where the faculty were both more open-minded and more emotionally mature), I struggled with instructors and students for reasons relating to this limp distinction. As a writer trying to make a career for himself, I struggled for a long time to find venues that would not reject my blended approach out of hand, and sometimes I still do.

Don’t cry for me, Argentina: I’m doing just fine, and in the long term I expect to do better. But it never feels good to see the things you love to make, and the things you often love to read, dismissed out of hand. Arthur Krystal thinks he’s being a brave truth-teller when he takes to The New Yorker to restate his opposition to including genre fiction in the category of literature, but he’s not being brave. Instead, he comes off as weirdly incapable of reflection. There have been a thousand articles like Krystal’s, and they always make the same very basic mistake: their conclusion (genre fiction’s inferiority to literary fiction) is also their premise. That is to say, they are begging the question. Click below the fold to see what I mean! READ MORE >

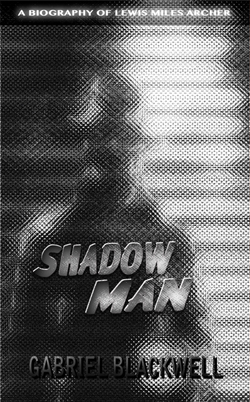

Weston Cutter interviews Gabriel Blackwell

I’m a huge admirer of Gabriel Blackwell — as prose editor at Noemi Press, I’m publishing his book of short fiction Critique of Pure Reason very soon, and I’ve published a piece of his body of work in almost every venue I’ve gotten my hands on. What I mean to say is that I can vouch for him as a writer and as a human being, and that you should also check out his novel Shadow Man, about which Weston Cutter has interviewed him. Here is Weston’s introduction, and their interview:

I’m a huge admirer of Gabriel Blackwell — as prose editor at Noemi Press, I’m publishing his book of short fiction Critique of Pure Reason very soon, and I’ve published a piece of his body of work in almost every venue I’ve gotten my hands on. What I mean to say is that I can vouch for him as a writer and as a human being, and that you should also check out his novel Shadow Man, about which Weston Cutter has interviewed him. Here is Weston’s introduction, and their interview:

Gabriel Blackwell’s Shadow Man: a Biography of Lewis Miles Archer arrived in black and white. I mean that both the galley copy was not full color, and that the book offers itself as a thing in or amidst a noirish fog, like some old cinematic masterpiece. Here’s how it starts: “Lewis Miles Archer, or anyhow the man known to creditors and clients as Lewis Miles Archer for just long enough to build up a respectable sheet of both, was born sometime between 1879 and 1888, somewhere in the shadow of Lake Michigan.” What Blackwell’s doing with this sort of dancing-away imprecision (four different states, for instance, could claim regions in the shadow of Lake Michigan) is crafting a slippery-but-detailed-as-possible biography of a fictional character. What actually happens to you as you read is you feel the line between ‘real’ and ‘fiction’ slipping, twisting and going porous in ways that, at least to this reader, become unsettling in fantastic ways: one less reads Shadow Man than goes into it and, later, comes out from it. It’s a hell of a thing. Gabe and I recently batted a single round of questions back and forth, hoping we’d get into more questions but then, after the first round, realizing 1) we’d gotten done what we’d hoped and 2) life intrudes.

Weston Cutter: Were there any rules in how you composed this book? In other words, did you keep 100% fidelity to the fictiveness of fiction and the ‘reality’ of reality? And how did this book end up taking the form it did? I guess mostly this question’s one rooted in fascination, one writer to another saying: how the fuck did you even find the trail that let you even begin to walk toward the result that is this book? How does one do that?

Gabriel Blackwell: I don’t think I thought of them as rules, but I guess they could be viewed that way—I created none of my characters and tried as much as possible to put the events from my texts (Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, and Ross Macdonald’s The Moving Target) into new contexts rather than invent other events to suit the narrative. But those didn’t seem like rules—I was just trying to write a book that worked in the way that I wanted this book to work. Shadow Man, which has to do with inheritance and imitation, needed to be a node rather than a terminal, a book that pointed outside of itself in constructive ways. I like lots of terminal fictions, books that assert that what they are describing is to be believed for the duration of their story and no further, books that begin and end inside the author’s head. But it’s rare that I’m actually caught up in those books; I’m always conscious of the writer playing house with me. That tends to take me out of it. I don’t want to read a transcript of someone playing with paper dolls, not if it isn’t really compelling. READ MORE >