No Tricks

Like many of us, I’ve read “On Writing” by Raymond Carver numerous times. It holds many useful ideas. There is a stage of our own creative writing. (I believe this phase usually arrives in the mid-20s, but possibly I am in error—perhaps it arrives after so many years of practicing the craft, not so much a writer’s age.) Either way, this stage involves reading copious interviews, craft books, and essays on writing, by writers. Apparently, as writers, were are seeking some golden ticket, some integral advice, etc. I believe most writers leave this period, and then, you know, write.

What is the most famous (or infamous) line from the Carver essay? No tricks.

“No tricks.” He says. “Period. I hate tricks.”

First, I like tricks. So what? Others have written the same. Second, Carver is wrong. He doesn’t hate tricks, he uses them. He especially employs tricks in the shorter form. Why? Because “tricks” are not tricks. Tricks are technique. Technique is important to the short story, very important to the sudden fiction, and absolutely essential to the flash fiction form. We flash writers have fewer words. We need artistry.

Let me show you Raymond Carver using some tricks. Read “Little Things” here.

OK, onward.

Constrain my writing.

From Rick Strassman’s book DMT: The Spirit Molecule. This is the way a DMT test subject named “Willow” described her experience on the psychedelic. I’ve added emphasis to the sentence that struck me:

The other side is very, very different. There are no words, body, or sounds there to limit things. I first saw deep space, white with stars. Then there was this multidimensional experience starting. It was alive. It was the aliveness that I heard.

And here, a quote from Terence McKenna recently reTumbled by Tao Lin: READ MORE >

Henry Kissinger on Writing

“Power is the great aphrodisiac.”

“Even a paranoid can have enemies.”

“Universal rule, to last, needs to translate force into obligation.”

“Multiple contests take place simultaneously in different regions of the board.”

“There are no isolated events.”

“Every civilization that has ever existed has ultimately collapsed.”

“The real distinction is between those who adapt their purposes to reality and those who seek to mold reality in the light of their purposes.”

“Each success only buys an admission ticket to a more difficult problem.”

“It is barely conceivable that there are people who like war.”

“I’ve always acted alone. Americans like that immensely.”

“The absence of alternatives clears the mind marvelously.”

“If you believe that their real intention is to kill you, it isn’t unreasonable to believe that they would lie to you.”

“Clausewitz’s famous dictum that war is a continuation of diplomacy by other means defines both the challenge and the limits of diplomacy.”

“Given the pace of technology, patience can easily turn into evasion.”

“Victory over the insurgency is the only meaningful exit strategy.”

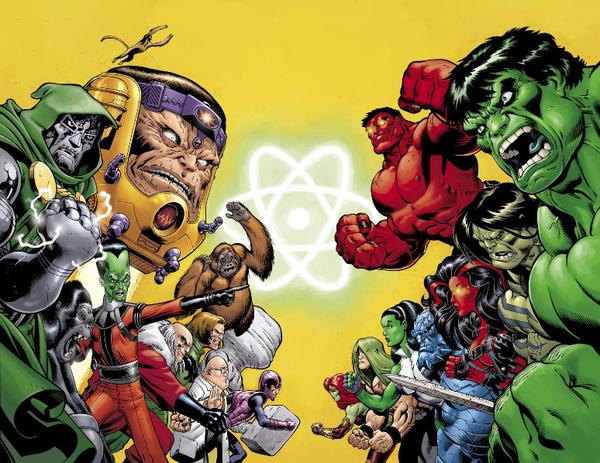

Superhero Wikipedia Pages: Hulk Guys Edition

HTMLGiant’s Superhero week has, like a day-glo-green mutagenic ooze, spilled over into an additional week, and may continue for all of the weeks to come, forever. In this post, I construct some (let’s call it) free-verse poetry from more Superhero Wikipedia pages, this time focusing on some of the Hulk characters. My feeling isn’t that the language of these things is beautiful, though it is sometimes what I would call incredible. What I find continually hypnotic is their dedication to story above all. CLICK BEYOND THE FOLD TO LEARN THEIR EPIC STORIES!

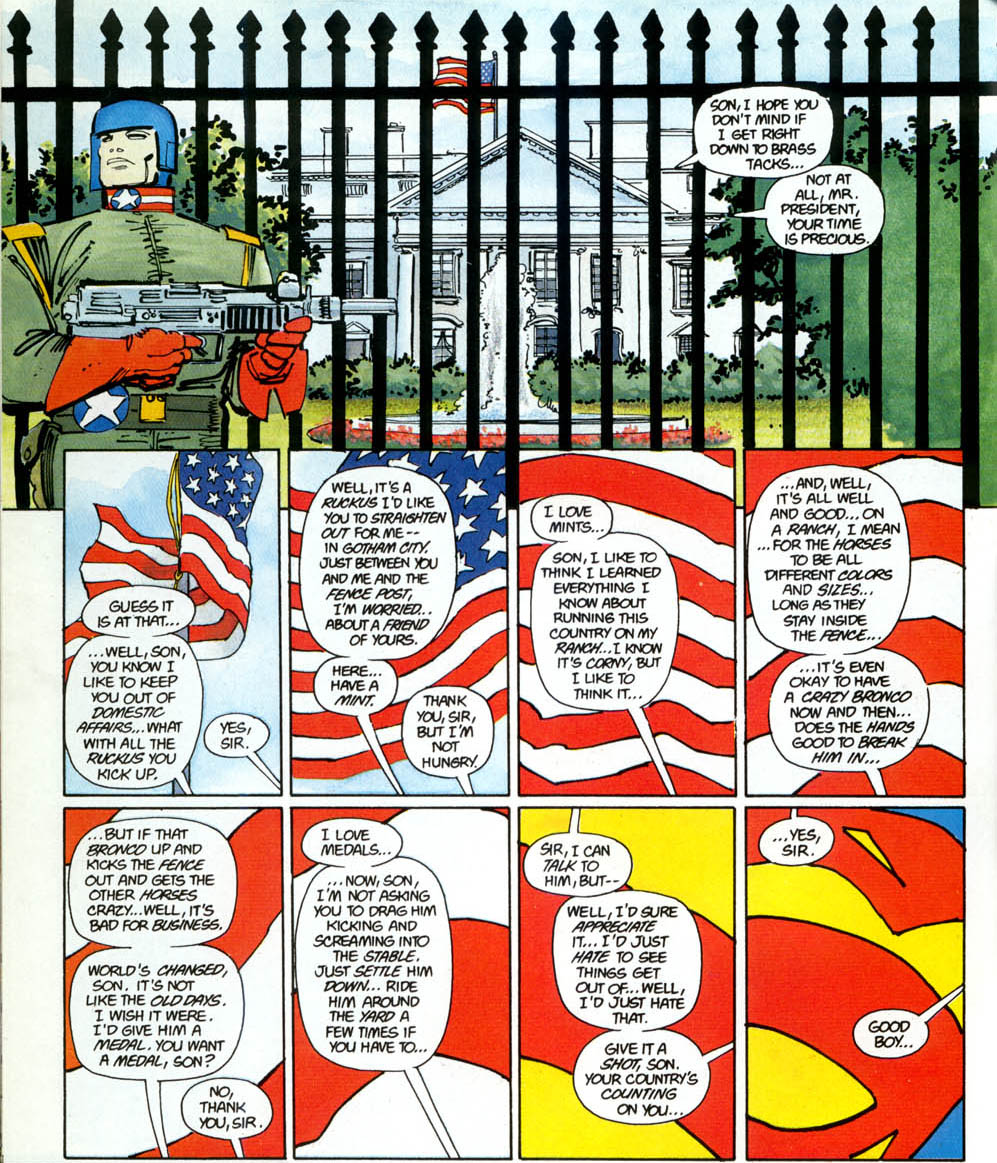

Reading Frank Miller’s influences on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy

One more post on the Batman, if you’ll please. It’s no secret that Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy drew a lot of inspiration from Frank Miller—specifically, from his 1986 mini-series Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and its 1987 follow-up, Year One (which featured art by David Mazzucchelli). And so I felt like taking some time to note all the connections (or at least the ones I can see—feel free to chime in as to what I’ve missed!).

I’ve already commented elsewhere on how Batman Begins took:

- the Tumbler design (The Dark Knight Returns);

- Batman’s escape from the police by means of a bat homing device (Year One);

- and the ending in which Commissioner Gordon muses about the arrival of the Joker, having received one of his calling cards (Year One).

And there are still more connections. Commissioner Gordon’s character arc in that film is similar to the one he follows in Year One—he even has a corrupt partner named Flass. Furthermore, Bruce Wayne distances himself from the Batman by cultivating the image of a drunken playboy:

That’s everything that I can see in the first film.

The Dark Knight is I think the least indebted to Miller of the three films. Nonetheless, its ending, wherein Two-Face kidnaps Gordon’s family, echoes the mob’s kidnapping of Gordon’s family at the conclusion of Year One—Batman even saves Gordon’s son from falling:

Moving on to the The Dark Knight Rises …

We Need to Talk About Batman

I want to argue that the conceit of Batman having a secret identity no longer works.

It once did, back in the 1930s and ’40s, when Batman was essentially a badass moonlighting in tights, socking hoodlums and thugs in their jaws. At that time, the extent of the audience’s suspension of disbelief was that the fellow wouldn’t get shot.

How simple, compared to today. The Batman of 2012 is a one-man paramilitary force capable of investing hundreds of millions of dollars into being the Caped Crusader—a one-man Blackwater USA! Frank Miller was right: there’s no way that the U.S. government would permit this guy to exist:

Games Taught Me to Care About You

When presented with bad design, I often become irrationally, almost violently angry. The first time I was exposed to the class registration system at NMSU, I was seated at a university computer, in a public place, with my wife. None of these things stopped me from thumping the desk with my fist after twenty minutes of trying and failing to make the goddamn thing do what I wanted. I have said that bad design actually makes me more angry than the Holocaust; this is true. Obviously the Holocaust was worse than bad design, but I have no direct experience of its horrors. Bad design is with us every day, corroding us inside and out. It feels more immediate, to me. It feels oppressive.

Bad design makes me so angry because it is a message from the world, a whisper. It says: “No one cares about you. No one knows that you exist. No one knows what you are like. No one has taken the time to imagine you. No one wants to think about what you need or want. You are profoundly unimportant.”

riting not riting

Some days it feels like pushing words around in a flat wheelbarrow. You write for hours with no real result, or with result far from satisfactory, or with result very far from satisfactory, as if you’ve lost the thing (always a fear), the thing that worked before but is now clearly not working (see David Duval, see Harper Lee [?], etc.). Were these hours wasted? In a busy life, could you have spent these hours on something clearly and concretely productive (mowing lawn, purchasing drugs, thinning mints, etc.)? Some bray, “Well, it all counts,” it is all grist for the mill, tourists for the ants, but possibly they are patronizing a person who just spent many fruitless hours staring at the whiteout conditions, the frowned forehead of the page. For me, a lifelong runner, I think of training. Some days I’m in a glow groove with running—the planned fartlek, tempo, hill surges, go exactly as I’d imagined.

Other days–and I learned this after decades of competitive running–the biorhythms are just funky-junked, right from the first warm-up step. There is immediately no flow. The legs are squid. So I usually shut that workout down. I switch the workout over to something less arduous, or I might just go play disc golf, or I might pop open a beer. That day wasn’t the day. Period. So maybe, in writing, we should do the same? Just accept the reality of the neurotransmitters and let it go. The other option—and, admittedly I’ve seen this work in running, though not so often—is to grind yourself into that space. Some read a book or lit mag, or listen to music (or write a blog post?), whatever, hoping to prime the engine, to transition into writing. Is that the better way? Or another? It’s something I’m pondering.

The Ever Risable Dark Knight

In the set piece that opens The Dark Knight Rises, a CIA operative screams at three hooded captives, “The flight plan I just filed with the Agency lists me, my men, Dr. Pavel here, but only one—of you!” He then starts pretending to toss them out of his airplane, only to be interrupted by the masked terrorist Bane, who has seen through his deceit (“Perhaps he’s wondering why someone would shoot a man … before throwing him out of a plane!”). Menacing banter ensues, after which Bane gains control of the aircraft and prepares to crash it. Grabbing Dr. Pavel, he commands an underling to remain on board, because “they expect one of us in the wreckage, brother!”

This is the kind of exchange Christopher Nolan thinks clever, when really it makes no sense. The plane was riddled with bullets, its wings torn away, its tail end blown off by explosives. Obviously somebody attacked it—so who cares if the bodies in the wreckage match the flight plan? What’s more, the CIA man wasn’t telling the truth about throwing them out—Bane even commented on that—so why trust his line about the flight plan?

These might seem like nitpicking, geeky griping over plot holes. But this exchange illustrates so much of what’s so wrong with Nolan’s movies.

For one thing, his characters never shut up.