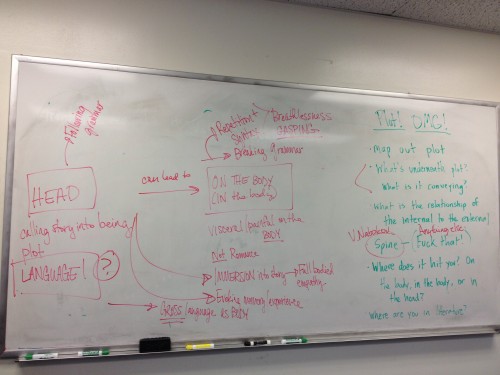

in which Lily teaches a class on a whiteboard

This is what happened in my grad Form & Technique in Fiction class today:

Here is how it happened. Every Wednesday, students read articles and essays that are NOT fiction. Last class, they read & we discussed a unit I called “The Human Body,” which included the following texts: Dong et al, “Unilateral Deep Brain Stimulation of the Right Globus Pallidus Internus in Patients with Tourette’s Syndrome”

(from The Journal of International Medicine); Grahek, Feeling Pain and Being in Pain, “Ch. 1: The Biological Function & Importance of Pain”; Ramachandran, Tell-Tale Brain, “Ch. 3: Loud Colors and Hot Babes: Synesthesia”; and

Scarry, The Body in Pain, “Ch.3: Pain and Imagining.”

Here is how it happened. Every Wednesday, students read articles and essays that are NOT fiction. Last class, they read & we discussed a unit I called “The Human Body,” which included the following texts: Dong et al, “Unilateral Deep Brain Stimulation of the Right Globus Pallidus Internus in Patients with Tourette’s Syndrome”

(from The Journal of International Medicine); Grahek, Feeling Pain and Being in Pain, “Ch. 1: The Biological Function & Importance of Pain”; Ramachandran, Tell-Tale Brain, “Ch. 3: Loud Colors and Hot Babes: Synesthesia”; and

Scarry, The Body in Pain, “Ch.3: Pain and Imagining.”

How To Be A Critic (pt. 5)

In part one of this series, I introduced a network of ideas aimed at rethinking our approach to criticism by foregrounding observation over interpretation, and participation over judgment, by asking what a text does rather than what it means.

In part two, I expanded on those ideas.

In part three, A D Jameson unwittingly offered a beautiful example of the erotics I have proposed, following the final imperative of Susan Sontag’s essay “Against Interpretation” — which, for the record is not called “Against A Certain Kind of Interpretation” but is in fact titled “Against Interpretation” — where she writes, “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.” To destroy a work of art, as Jameson’s example shows and as Sean Lovelace has shown (1 & 2) and as Rauschenberg showed when he erased De Kooning, certainly counts as an erotics, which for me far surpasses the dullardry of interpretation.

In part four, A D Jameson unfortunately embarrasses himself by indulging his obvious obsession with this series. Whereas one self-appointed guest post might seem clever or even naughtily apropos, two self-appointed guest posts (in addition to all of his contributions in the comment sections) conjures the image of a petulant child acting out in hopes of garnering his father’s attention. (Daddy sees you, Adam. He’s just busy doing work right now.) Yet, despite his cringe-worthy infatuation, the example he offers is an effective one. I applaud it. (As Whitman said, “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / I am large, I contain multitudes.”)

This time, I’ll do a little recapitulation, elaboration, and I’ll introduce other lines of flight. But first, an important note about the necessity of revaluation. (Following Nietzsche’s project, of course. Itself predicated on Emersonian antifoundationalism, of course.)

How To Be A Critic (pt. 4)

Resist making value judgments.

How To Be A Critic (pt. 3)

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 1: What is a concept?

Sol LeWitt: “Wall Drawing #1111: A Circle with Broken Bands of Color” (2003, detail). Photo by Jason Stec.

[Update: Part 2 is here.]

I wrote about this to some extent here, but I wanted to expound on the issue in what I hope is a more coherent form. Because I frequently see concepts confused with constraints, and the Oulipo lumped in with conceptual writing. For instance, this entry at Poets.org, “A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry,” states:

One direct predecessor of contemporary conceptual writing is Oulipo (l’Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a writers’ group interested in experimenting with different forms of literary constraint, represented by writers like Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, and Raymound Queneau. One example of an Oulipean constraint is the N + 7 procedure, in which each word in an original text is replaced with the word which appears seven entries below it in a dictionary. Other key influences cited include John Cage’s and Jackson Mac Low’s chance operations, as well as the Brazilian concrete poetry movement.

I would argue that the Oulipo, historically speaking, are not conceptual writers/artists—although it’s easy to see how that confusion has come about, because the Oulipians have proposed some conceptual techniques, such as N+7 (which I’d argue is not a constraint). (Also, it’s each noun that gets replaced, not each word.)

What, then, distinguishes concepts from constraints? And why does that distinction matter? In this series of posts, I’ll try answering those questions, starting with what we mean when we call art conceptual.

Mark Zuckerberg on Writing

“The goal wasn’t to make a huge community site; it was to make something where you can type in someone’s name and find out a bunch of information on them.”

“I just think people have a lot of fiction… I mean, the real story is actually probably pretty boring, right? I mean, we just sat at our computers for six years and coded.”

“A squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.”

“The only meat I eat is from animals I’ve killed myself.”

How To Be A Critic (pt. 2)

Young Critic Engaging with John Lavery’s

“Portrait of Anna Pavlova” (1911)

In Part One of this series, I introduced a network of ideas aimed at rethinking our approach to criticism by foregrounding observation over interpretation, and participation over judgment, by asking what a text does rather than what it means. This time, I’ll expand on those ideas.

The young girl in the picture above demonstrates an angle on the critical practice I proposed. She also brings to mind what Nietzsche said about the ideal reader in Ecco Homo, “When I try to picture the character of a perfect reader I always imagine a monster of courage and curiosity as well as of suppleness, cunning and prudence—in short a born adventurer and explorer.”

The critic as monster, performer, participant, adventurer, explorer.

Brian Evenson Gives Advice for Future MFA Applicants

Advice for Future MFA applicants:On a more serious note, now that I’ve almost read through this year’s batch, here’s the advice I’d give off the top of my head to future MFA fiction applicants. Most of the applicants were interesting people and trying hard and it’s deeply appreciated, particularly when I’m reading so many applications. I don’t think any of the applications I read this year had a single malicious bone in their body. But here are a few things that I would want to be told if I was thinking about applying. Please feel free to steal, revise, mutilate, or dispute:1. Turn in your very best piece of fiction. This really, really matters to me, more than anything else. If I love a piece of writing, I will fight for it, and am willing to overlook a multitude of other sins.2. Better to turn in one shorter excellent piece than a good piece and one bad one. Don’t turn in work just to max out the page limit. And if you’re finding yourself trying to cram all sorts of things into the page limit by changing the font and single-spacing, then step back and take a deep breath and think again.

3. Don’t try to pretend you’re something you’re not. Most of you don’t, and those of you who do don’t do it maliciously, but just kind of slowly convince yourself into it as you write and rewrite your application. Look, it’s easy to tell if you’re faking. So don’t fake.

4. Be honest, but “we’re dating and getting serious” honest rather than either “First date honest” or “Now that you’ve proposed, here’s all the stuff you need to know about me (like the fact that I killed my first wife)” honest. You can and should talk about your struggles and successes and trials and etc., but in moderation.

5. In the personal statement, write about yourself in a way that allows us to get a real sense of you and the way you are now, right now, and where you’re going. If you feel you have to go back to childhood to do that, that’s okay, but if I go away with a better sense of how you were when you were in 2nd grade (or whatever) than how you are now, that’s not good.

6. Read interesting things and learn how to talk about them in interesting ways. Read, read, read. And read eccentrically. Take chances. There’s no reason, no matter what your job or your circumstances, that you shouldn’t be reading an interesting book every week or two, and that’ll do a great deal for your development as a writer and as a person. It’s okay to let us know what books led you to writing, but better if we find out what books you continue to go back to and who you’re interested in now.

7. Don’t pretend to have read something that you haven’t read. Don’t google the faculty at a program and then try to include a line in your personal statement that suggests what their book is about. This rarely works, and as a result usually does more harm than good.

8. We’re interested in knowing what makes you unique, but within reason. And even if you have a great set of experiences and are incredibly interesting and we’d love to have an 8-hour long coffee with you to learn about your experiences running Substance D. from the American camp to the Norwegian camp in Antarctica, if your writing sample isn’t good enough you won’t get in. There comes a time when you need to choose to work on the writing instead of getting life experience as a carny.

9. If you already have an advanced degree, you have to explain convincingly why you want to get another, and why we should give this opportunity to you rather than to someone else. If you already have a PhD, we need to be convinced that this is the right thing for you and for us, and that you’re not just collecting degrees. But, honestly, the default acceptances for MFAs is usually (but not always) someone who doesn’t yet have an advanced degree. We’ve taken people with advanced degrees in our program, but it’s very much the exception rather than the rule.

10. If you already have a book out, same thing. Are you serious about improving your writing or do you want to treat this as a sort of an artist colony? If the latter, well, I’d suggest an artist colony: they’ll feed you, and we usually won’t. If I get the impression that you want to get the MFA mainly to have a teaching credential, that can be one or more strikes against you.

11. MFA programs make mistakes. We don’t always see the potential of people, which may be partly our fault and partly your own. Do everything you can when you put together your application to make sure that the fault is on our side rather than yours. But also remember: any really good program ends up with many more people they’d like to admit than they actually can admit. When it comes down to that final cut, it’s very very hard, and we’ll have to let people go who, ideally, we’d love to have come. So, if you don’t get in, don’t take it as a judgement. To our shame, we’ve turned down many great writers before, and probably will again. But fingers crossed that it won’t be you…

Good luck!

Best,

Brian

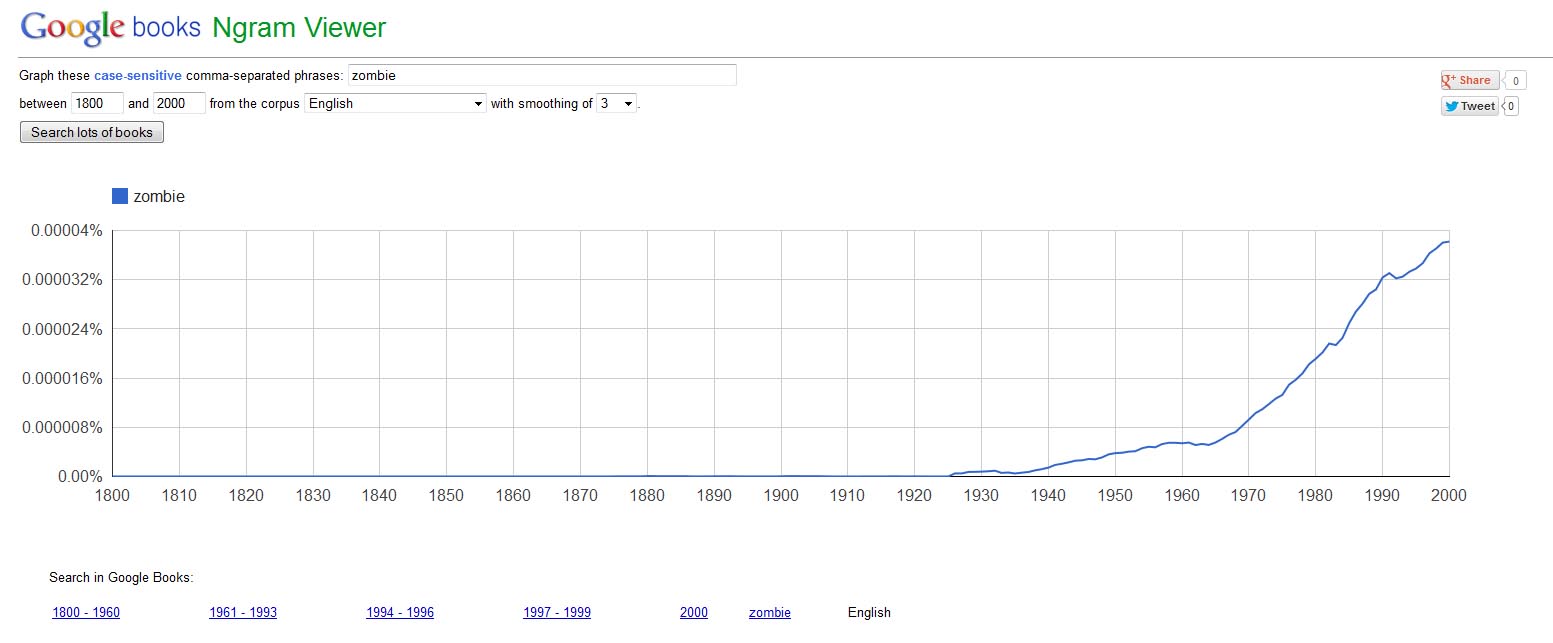

What to call a zombie when? Some tools to assist with period-accurate writing

Over at io9 there’s this post, “How to make sure the language in your historical fantasy novel is period-accurate.” And while “fantasy novel” and “period-accurate” seem contradictory to me, I was happy that the article directed me to two interesting online resources that may also interest . . . you!

1. The Jane Austen Word List: Author Mary Robinette Kowal compiled a list “of all the words that are in the collected works of Jane Austen” (14,793!). You can install it as a “language” in OpenOffice (click here for instructions), then spell check your document against it, which will highlight any words that Austen didn’t use. (Kowal: “It also includes some of Miss Austen’s specific spellings like ‘shew’ and ‘chuse.'”) This would obviously be useful for anyone who wants to write a project using only Austen’s vocabulary. And assuming that Kowal didn’t slip up, we can see that Ms. Austen’s works are zombie-free, the only z-initial words that she used being zeal, zealous, zealously, and zigzags. (Sorry, Seth Grahame-Smith.)

2. The Google Ngram Viewer: This allows you to see check how frequently a word appears over time in any book that Google Books documents. So, for instance, here are the results for “zombie”: