I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 1 (The Ghosts of I’ll Drown My Book)

This is Part 1 of a week long feature on I’ll Drown My Book, the new anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press.

Stay tuned all week for more…

6/4 Monday – Part 1: Review by Janice Lee

6/5 Tuesday – Part 2: Review by Molly Brodak

6/6 Wednesday – Part 3: Review by Nicholas Grider

6/7 Thursday – Part 4: Review by Janey Smith

6/8 Friday – Part 5: Brief interview questions with the anthology’s editors

*** READ MORE >

June 4th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

“C, Clown”: An Excerpt from Gwenaelle Aubry’s No One

I’m five or six, on holiday with my father at his parents’ place in Soissons. My grandfather is seeing patients in his surgery at the end of the garden, my grandmother is busy doing I don’t know what, I’m alone, I’m bored. Suddenly I have an idea. I get my grandmother’s lipstick from the bathroom and I set about painting my father: two circles on his cheeks, another on the end of his nose. I take him by the hand and say, “You’re a clown, Dad, come on, I want to show everyone.” Together we go out into the street and sit down on the doorstep in the blazing sunlight of a summer afternoon. He’s in profile. With my finger I spread the color over his left cheek. He lets me do it with a weary, nasty smile. Seeing him like this I’m filled with shame, sorrow, and pleasure. My grandmother suddenly appears from nowhere, a small, elegant, measured woman, her dress, makeup, and hair always just so. For the first time I hear her raise her voice. In a tone that brooks no answer she orders me to stop it at once, to go back inside.

Twenty-five years later, when my grandmother was long dead, my father went back to live, or rather to stop living, in Soissons. He moved into an apartment with his father. After my grandfather’s departure and subsequent death a few months later, my father was hospitalized in a clinic right opposite the house he grew up in. It was then that he really went downhill. READ MORE >

January 12th, 2012 / 12:01 pm

HTMLGIANT’s Tournament of Bookshit

This year in place of our regular “Mean Week,” HTMLGIANT will be running something we’d like to call our Tournament of Bookshit, in which 64 book related shits will be placed into an NCAA style bracket to square off and determine, by the most arbitrary means possible, [something]. What that [something] is I have no idea, but I do know that our tournament will operate by the same wily-nily sure let’s do it this way found in most any literary competition, whether it be list making, book jousting, or whatever else you’ve got.

Below you’ll find a list of the 64 entities selected pretty much on a whim to be our contestants. They’re silly. For each round a guest judge of various description and sensibilities will analyze each in light of each other and then select one by whatever terms they like to go forward, with perhaps a Mean Week attitude in mind. In the end, we’ll crown a very special winner the King Shit Mountain of Super Bookshit.

We’ve also set up, for those taking score at home, a bracket system where you can fill out your predictions if you want. It requires you to sign up but only takes a second. At the end we’ll have a prize pool of literary stuff to give to whoever somehow pulls that magic high score out of the hat of darkness.

Any authors/publishers/etc interesting in throwing in on the prizes, please leave a comment with what you’d like to give away and we’ll include it in the winnings and link it in a round up of Kind Souls.

Registration and prediction is free and will be open until the first decisions begin posting on Wednesday around Noon. Playoffs will continue at whatever pace they continue at.

The contestants: READ MORE >

November 28th, 2011 / 11:04 am

An Interview with Michael Martone

Depending on whom you ask, Michael Martone is either contemporary literature’s most notorious prankster, innovator, or mutineer. In 1988 his AAP membership was briefly revoked after Martone published his first two books—a “prose” collection titled Alive and Dead in Indiana and a “poetry” collection titled The Flatness and Other Landscapes—which, aside from The Flatness and Other Landscapes’ line breaks, were word-for-word identical. His membership to the Alliance of Icelandic Writers was revoked in 1991 after AIW discovered that, while Martone’s registered nom de plume had been “born” in Reykjavík, Martone himself had never even been to Iceland. His AWP membership was revoked in 2007, reinstated in 2008, and revoked again in 2010.

After his first two collections, Martone went on to write Michael Martone, a collection of fictional contributor’s notes originally published among nonfictional contributor’s notes in cooperative journals, The Blue Guide to Indiana, a collection of travel articles reviewing fictional attractions such as the Musée de Tito Jackson (most of which were, again, originally published as nonfiction), a collection of fictional interviews with his mentor Kurt Vonnegut, fictional advertisements in the margins of magazines such as Tin House and Redivider, poems under the names of nonfictional colleagues, and blurbs for nonexistent books.

But his latest book is perhaps the most revealing—Racing in Place is a collection of essays on Martone’s obsession with blimps, basketball, and the Indianapolis 500, symbols for him of “this kind of frenetic motion and also this kind of staticness in the Midwest.” Born in Northport, Michigan, Martone has often been described as a regionalist, and his relationship with the Midwest mirrors his relationship with literature: Martone thinks of the Midwest as a “strange, imaginary place, with no distinct borders or boundaries.”

Martone now lives in Tuscaloosa, where he teaches in the MFA program at the University of Alabama. In spring 2011 Martone was arrested outside of Golyadkin’s Pub in Tuscaloosa for assaulting, allegedly, the writer Thomas Pynchon, allegedly. During Martone’s six-week sentence at Tuscaloosa County Jail, I was approved for a “non-contact visit” for our interview: meaning that Martone and I could meet face-to-face, but separated by a panel of bulletproof glass, talking to each other over yellow telephones. (It’s unclear why Martone wasn’t allowed a “contact visit”—typically an inmate serving time for a misdemeanor, especially one with a sentence as brief as Martone’s, is granted contact visits as a matter of routine, SOP—when I asked Martone about it, he refused to answer my question.) Martone wore an orange jumpsuit, did not wear but instead held a pair of tortoiseshell eyeglasses, and had not shaved since his incarceration. I was allowed one pen and one pad of paper—nothing more.

Upon his release, Martone and his wife left for Frankfurt, Germany, where they will spend what remains of his sabbatical year.

July 14th, 2011 / 1:32 pm

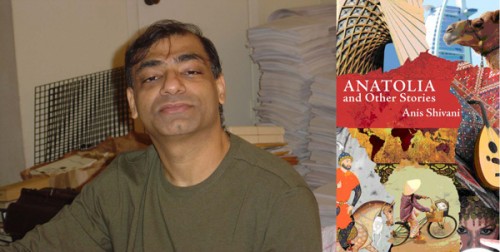

A Conversation With Anis Shivani

I am always fascinated by people with whom I disagree, vehemently and sometimes violently, about matters of mutual interest. I have read some of the literary criticism Anis Shivani has written for The Huffington Post and in other venues and regardless of his subject matter, I always have a reaction, usually a reaction that is anything but subdued. Nine times out of ten, I disagree with what Shivani has to say about everything and anything. I suppose that is the mark of a critic who is doing their job effectively–inspiring a reaction, a conversation, a response to their ideas. I am especially curious about what makes Shivani tick because he seems so committed to his opinions on the one hand, and so committed to provocation on the other, though, as you’ll see, he would disagree with that latter statement. I don’t know that you can ever really know how someone thinks or what motivates them but I asked Shivani a few questions about contemporary literature, criticism, the role of the critic, and how he approaches his critical work. He had, as you might imagine, a great deal to say and I disagreed, as you might imagine, with much of what he had to say but as ever, I had a reaction, a response and we had an interesting conversation.

You do a lot as a writer–fiction, poetry, criticism. What is your first love?

Fiction has always been my first love. I write criticism to learn more about fiction. I could also easily have devoted myself to poetry, but although poetry is satisfying in its way, only in fiction does my soul fully engage. There’s no rush like writing fiction, and I can’t do it on autopilot, as it’s possible to do with criticism or even poetry at times. The feeling of euphoria and satisfaction from writing fiction is incomparable. Writing a successful novel is a great challenge, and you have to be a bit of a poet, a bit of a critic, a bit of a dramatist, a bit of a philosopher, a bit of a social scientist, to pull it off. Writing long poems is more exciting than short lyrics, but then one needs a lot of commitment for that. I’m in two minds about having written so many stories early in my career; on the whole perhaps it was a net loss, because I didn’t spend that precious time writing novels. The economics of publishing dictated that I write short stories for many years and get them published in the literary journals, but the story requires a different mindset than a novel and it’s difficult to get the story’s habits out of the mind when one is writing a novel. It teaches compression, which is both a virtue and a fault.

It’s only an unfortunate specialization that limits writers to operating within narrow genres—short stories about a specific region and milieu, for example, or novels dedicated to the same few characters, or lyrical poems relentlessly exploring one’s own ethnicity or geography—otherwise writers in other countries still write in different genres at the same time, and this has always been the case since the beginning of time—until, that is, the academic specialization of literary writing under university patronage in the U.S. in the late twentieth century. I think writers should see themselves as workers in the broad field of the arts—including even Hollywood or popular music, and certainly what used to be called literary journalism in every possible genre. Anything to break the rut, to push the mind toward new challenges so that writing doesn’t fall into preestablished grooves—which is very easy to do, based on the successful formulas in existence. Film is a particularly fruitful cross-fertilizer, as is painting. Really, the arts cannot function in isolation and shouldn’t be practiced and critiqued that way. It’s only unprecedented specialization that has created this unnatural situation, and the writer must be very conscious of that and work hard to break down the false institutional barriers preventing a catholicity, even eccentricity, of interests. The mind desires to switch between different levels of intuition and emotion and logic and these desires should be fed.

June 22nd, 2011 / 4:39 pm

I Want It All To Be Kind of Shitty: An Interview with Johannes Göransson

I can’t say enough about how important the work of Johannes Göransson has been to me, both as a field of language and image, and as a person. Besides co-editing both Action Books and Action Yes, two places where you can always depend on reading work that is new, singular, challenging, and actually fun, he has published four full length books of his own work, including Dear Ra, A New Quarantine Will Take My Place, Pilot, and most recently Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate from Tarpaulin Sky, as well as translations of important Swedish writers like Aase Berg and Johan Jönsson [if you haven’t read his Swedish issue of Typo, holy shit], and wrangling of the insane machine that is the hybrid litblog Montevidayo. Not to mention being a teacher (which, when reading some of his students’ work, and what mechanisms he gets out of them so early, equals a particular feat), a father, a husband, and a person. In no small words, a fucking force.

Over the past few weeks I exchanged emails with Johannes about all of the above and more.

* * *

BB: I remember reading pieces of the Pageant years ago I think under the name New Torture Operations, yeah? How did this project begin and manifest itself into the book it is, on an assemblage level?

JG: Yes, I think that was one early version of what became, among other things the pageant. It also became the second half of the performance piece The Widow Party and my novel Haute Surveillance (which is not published). Assemblages do play a big part in the way I compose these. In part they come out of a piece I wrote over a couple of years a few years ago, The Black Out Sessions or The Secessions (it has many names), and which I haven’t and won’t publish (well I did publish some of them before deciding that it wasn’t the right thing to do), but from which I create various assemblages – such as in The New Torture Operations, The Widow Party and Pageant, all of which form assemblages between torture and fashion, the anorexic body and performance, atrocity and kitsch, colonialism and the nuclear family.

When I was working on these Black Out Sessions I was also studying Brazilian-Swedish artist-poet Oyvind Fahlstrom’s work from the 1950s and 60s and he uses this funny pun – he doesn’t make “collage,” he says he makes “kalas,” which is Swedish for “party”. And the way this works out is that his artworks parties (though it’s usually translated as “feast”) on other works of art or texts. So there’s a party on Mad Magazine, or a party on Burroughs etc. So the Black Out Sessions were parties on just about anything I could find. I was both very creative and totally unfocused so I decided this wasn’t a finished text but something that I would party with/against/on with these other manuscripts. The Black Out texts became a kind of “party” energy which I used on other texts and subject matters to form assemblages. In the particular pieces that are in The New Torture Operations and pageant are parties on this 19th century antique textbook a student gave me years ago – what every student needs to know about the world. This includes chapters on astronomy, “The Vasty Deep,” and “The Flowery Kingdom” (China). A lot of what a student needs to know, it turns out, is about the morality of various colonial ventures (Stanley and Livingston get their own full chapter). Interestingly my home country of Sweden gets I think one sentence in a paranthesis and it’s something like “… (in difference to the Scandinavian countries, about which not much is known other than that they are the ugliest and least intelligent of people).”

June 2nd, 2011 / 1:15 pm

HTMLGIANT INTERACTIVE FEATURES #43: Psychological Realist Story-Generating Machine (Reader Participation Welcome In the Comments Section)

Instructions:

1. Don’t be lazy. This machine isn’t going to write your story for you. It’s just going to provide your parameters.

2. You can drink beer while working with the assistance of the machine. But cut the Bukowski crap, cowboy. You need to be sober READ MORE >

April 18th, 2011 / 7:01 am

That Paradoxical Kind of Attention: An Interview with Matt Bell

Last year saw the release of the first full length work by a much buzzed and discussed and well admired presence both online and in print, the seemingly inexhaustible Matt Bell. Between his countless writing projects, his editorship of The Collagist and role on the masthead at Dzanc Books, to relentlessly blogging and spreading the word all over the place not only about his own work, but scads of other, I don’t think there’s anybody who would argue Matt Bell isn’t an enormous lodestone-type presence for the independent press world, and always on the prowl.

Over the past few months, Matt and I exchanged a bunch of emails, some days apart, some weeks, in the midst of all this, conversing about the book, How They Were Found, Matt’s fortitude and unwavering ambition, process, sound, and many other things of the word.

BB: So, as a collection, How They Were Found represents a pretty wide arc of time and writing for you, yes? I remember “A Certain Number of Bedrooms, A Certain Number of Baths” from Caketrain several years ago being a story that was probably the first of yours I read and was like Yes, this man’s mind: there is aura here. I think I’d actually read all of the stories except one perhaps in journals since then, and was really impressed in the reading of them as a whole object how they really seemed to comprise a sense of a whole, even over such a course.. I wonder how it feels now to you to see all that time represented in an object, and if the parts as parts became different to you once they were assembled into that body? Also, how did you go about figuring out what stories from that time should go into the book and what should be left out?

MB: The time span of How They Were Found is a weirdly elongated space, because while I wrote “A Certain Number of Bedrooms, A Certain Number of Baths” in 2006–looks like I did the first draft in March of that year–I didn’t write any of the other stories in the book until 2008. The next earliest is “Hold on to Your Vacuum,” written in January of that year, and then “Ten Scenes from a Movie Called Mercy,” written a month or two later. Staring six months later, say August 2008, I wrote all of the rest of the stories that are in the book, meaning that ten of the thirteen were written between August 2009 and May 2010. So in one sense the book took me five years to write, and in another I wrote the bulk of the book in eight or nine months. The truth is probably that it was both, and that what I didn’t realize was starting with “A Certain Number of Bedrooms” just took a couple years to play out. What I remember of writing that story is that it came out almost effortlessly, in a way almost nothing does now: I had a first draft in a single day, and while it took a while to polish it–I literally just stopped, in some ways, since I tweaked a few sentences between the galleys and the final of the book–but ninety or ninety-five percent of what’s in the final version is in the first. It was something new for me, different than what I’d done before, and while I’d like to say that writing that story instantly helped me get to where I could write the rest of the stories in the book, it didn’t. I didn’t write anything else like it for a long time, didn’t even know enough to recognize how different it was from what else I was doing.

March 30th, 2011 / 9:17 am

An Interview with David Cotrone of Used Furniture Review

Ryan Call: Tell me a little bit about yourself. I’ve seen your name and writing around online, and I know you live in Plymouth, MA, but other than that, I don’t know much about you.

Ryan Call: Tell me a little bit about yourself. I’ve seen your name and writing around online, and I know you live in Plymouth, MA, but other than that, I don’t know much about you.

David Cotrone: No worries; there’s still a lot I don’t know about me, too. But here’s what I do know: I’m currently a student at a school in Massachusetts. I’m afraid of driving a car.

RC: Wait, why are you afraid of driving a car?

DC: I don’t know, really. Maybe it’s because I have visions of losing control of the wheel, or of another driver taking me out. Or maybe I’m afraid to move in vehicle that’s not my own body because my body’s exactly what I’m not yet comfortable with–rather, the thing that controls my body. So I speak to this thing at night. Converse. Get to know it. Make peace. Repeat. READ MORE >

February 10th, 2011 / 12:06 pm

Glam Lit: Eight questions from the Jaipur Literature Festival

The DSC Jaipur Literature Festival, held January 21-25 at the Diggi Palace in Jaipur, India, is the biggest literature festival in the Asia Pacific region and supposedly the biggest free literature festival in the world. I spent the festival investigating the new culture of literary glamour that has arrived in the subcontinent.

i. Do glamour and literature make good bedfellows, or should they stop hooking up?

Jaipur is a city on the edge of desert. It is a few-hour or half-day drive from New Delhi (depending on who you’re asking), which is India’s publishing and intellectual capital. I’ve never been to The Hamptons, but Jaipur feels like it could be an equivalent, except the white linen and Bentleys are exchanged for multicolored, mirror-work ethnic wear and camel carts. It is also the bastion of very old money, meaning the town is populated with the offspring of an 11th century clan of feudal rulers known as the Rajputs, who built hundreds of opulent palaces, most of which have been turned into tourist attractions or guest houses.

Scene from the balcony of the crowded Jaipur Literature Festival front lawns.

Hearing writers speak under grandly decorated tents at a Rajput mansion built in the 1860s gives all of the Jaipur Literature Festival’s events (even a panel named “The Return of Philosophy”) an inherently glamorous feel. Glamour is defined as “the quality of fascinating, alluring, or attracting, especially by a combination of charm and good looks,” and it is the preposition that makes me suspicious when it comes to the literary scene. But maybe, just two months in to a year of living in India, I’m just not used to it. Because in my experience, book events in America are held in convention center rooms under florescent lights, or in the children’s section of a bookstore set with uncomfortable folding chairs, or in the usual stronghold of American literary glamour: the grimy bar. READ MORE >

February 1st, 2011 / 10:56 am