Craft Notes

Another way to generate text #7: Gysin & Burroughs vs. Tristan Tzara

A while back, I ran a little series, “Another way to generate text.” The first one proved fairly popular, and I’ve been meaning to make more of them, but generative techniques haven’t been on my mind. However, my post last week, “Experimental fiction as principle and as genre,” generated a lot of text (haha), in the form of comments. Some people who chimed in questioned whether the Cut-Up Technique that Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs developed and used in the 1950s was ever all that experimental. Specifically, PedestrianX wrote:

I find it hard to accept this argument when its main example, the Cut-up, didn’t start when you’re claiming it did. I’m sure you know Tzara was doing it in the 20s, and Burroughs himself has pointed to predecessors like “The Waste Land.” Eliot may not have been literally cutting and pasting, but Tzara was.

This comment got me thinking about the role influence plays in experimentation; more about that next week. Today I want to address the point PedestrianX is making, as it strikes me as pretty interesting. Were Gysin and Burroughs merely repeating Tzara? Or were they doing something substantially different?

To figure that out, I decided to run through the respective techniques, documenting what happened along the way. Because if I’ve learned anything in my studies of experimental art, it’s that thinking about the techniques is usually no substitute for sitting down and getting one’s hands dirty.

If you want to get dirty, too, then kindly join me after the jump . . .

For this project you will need:

- two copies of the same text;

- a pair of bright orange safety scissors;

- a straightedge;

- a large sheet of paper (to protect your work surface);

- a large clean place to work far away from the crushing adult responsibilities you’re avoiding;

- nothing better to do with your time;

- (optional) lots and lots of coffee (OK that’s less optional than you might think).

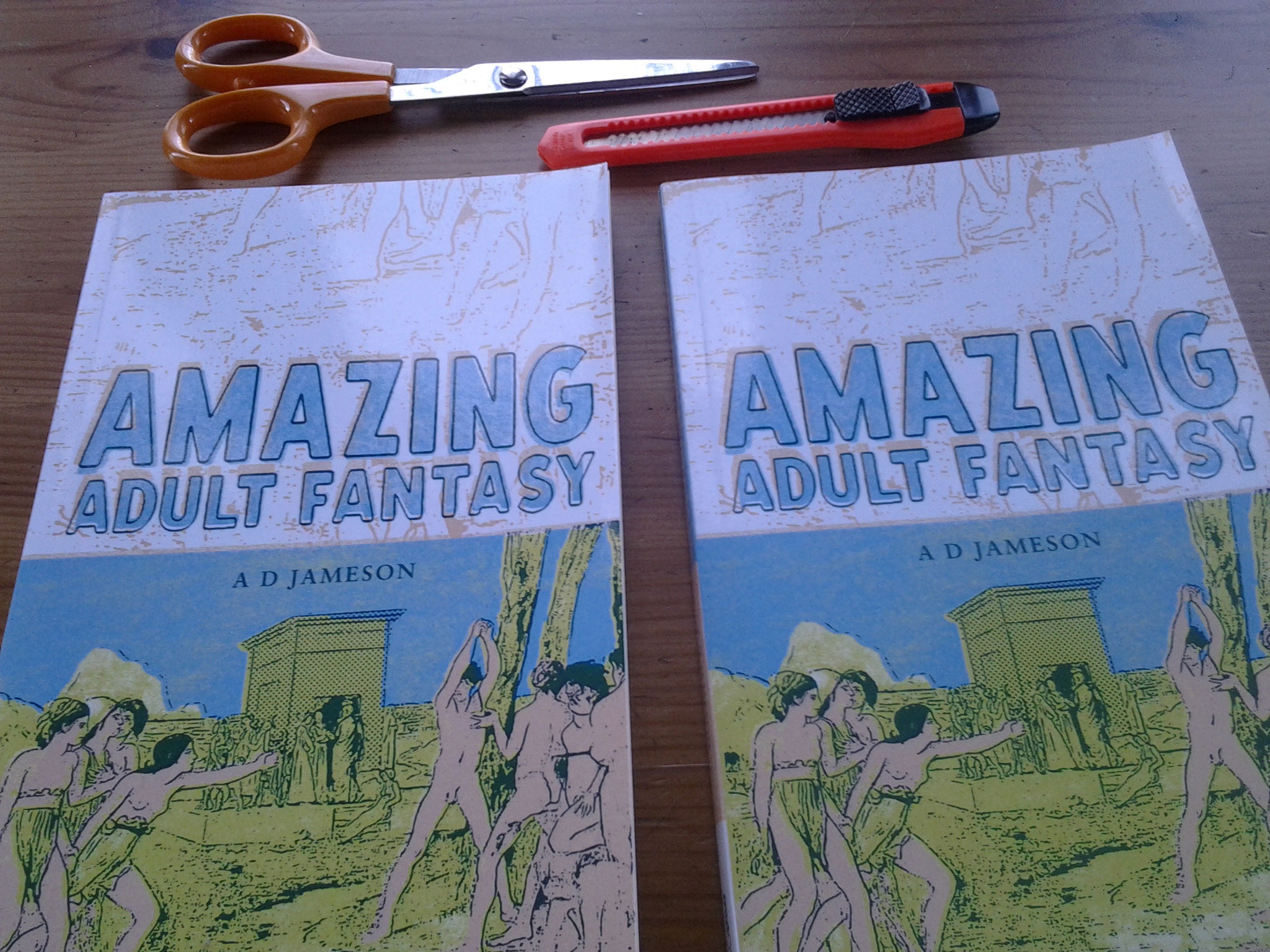

For my text I used two copies of my first book, Amazing Adult Fantasy, since I have literally stacks of them mouldering in my apartment. Note that if you choose to repeat this project with my book, you will want to play it safe and buy seven or eight copies.

1.

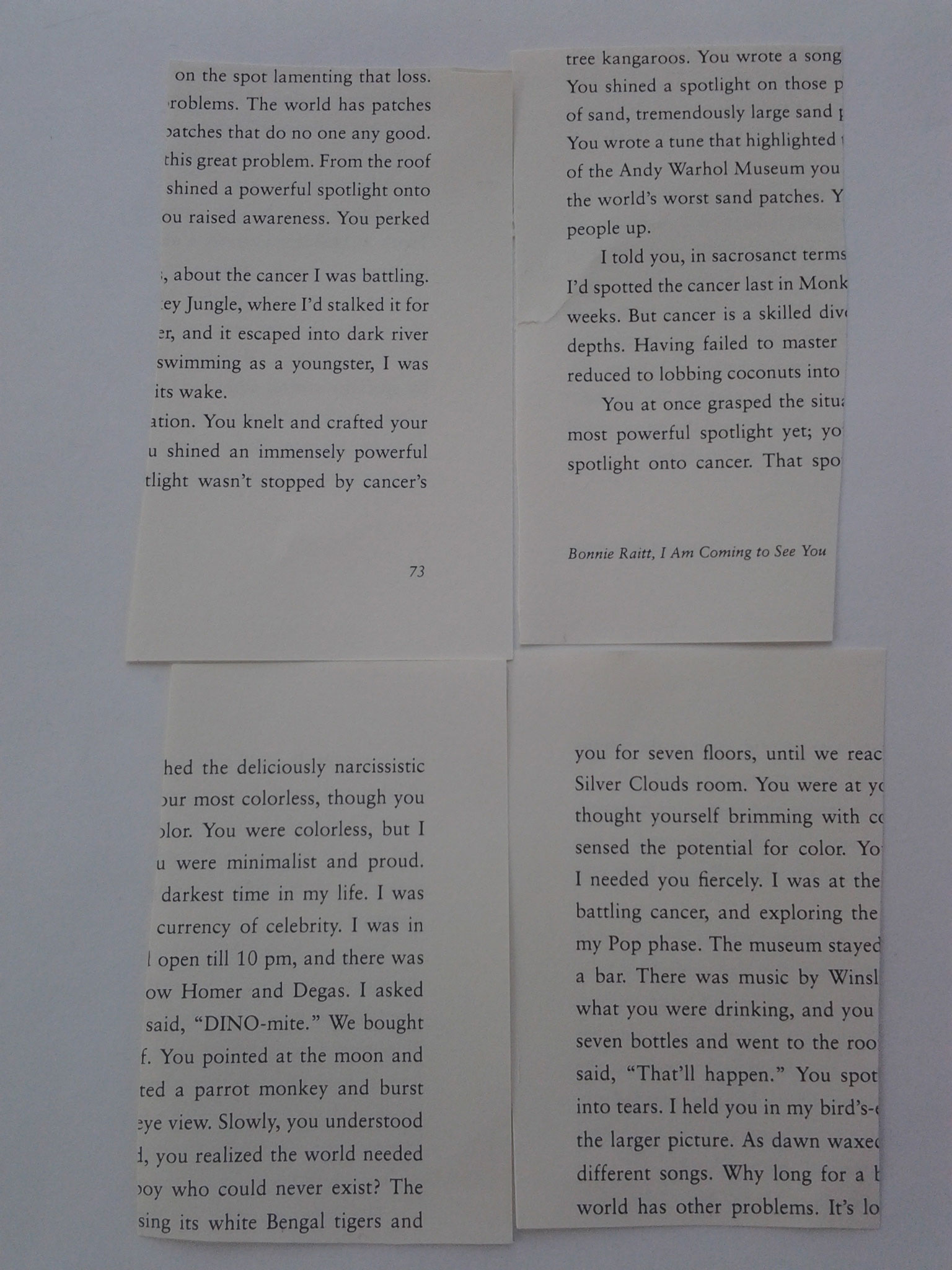

First, I randomly selected a page in the book—page 73. Well, it wasn’t entirely random. I wanted a page with lots of text on it. Page 73 fit that bill.

2.

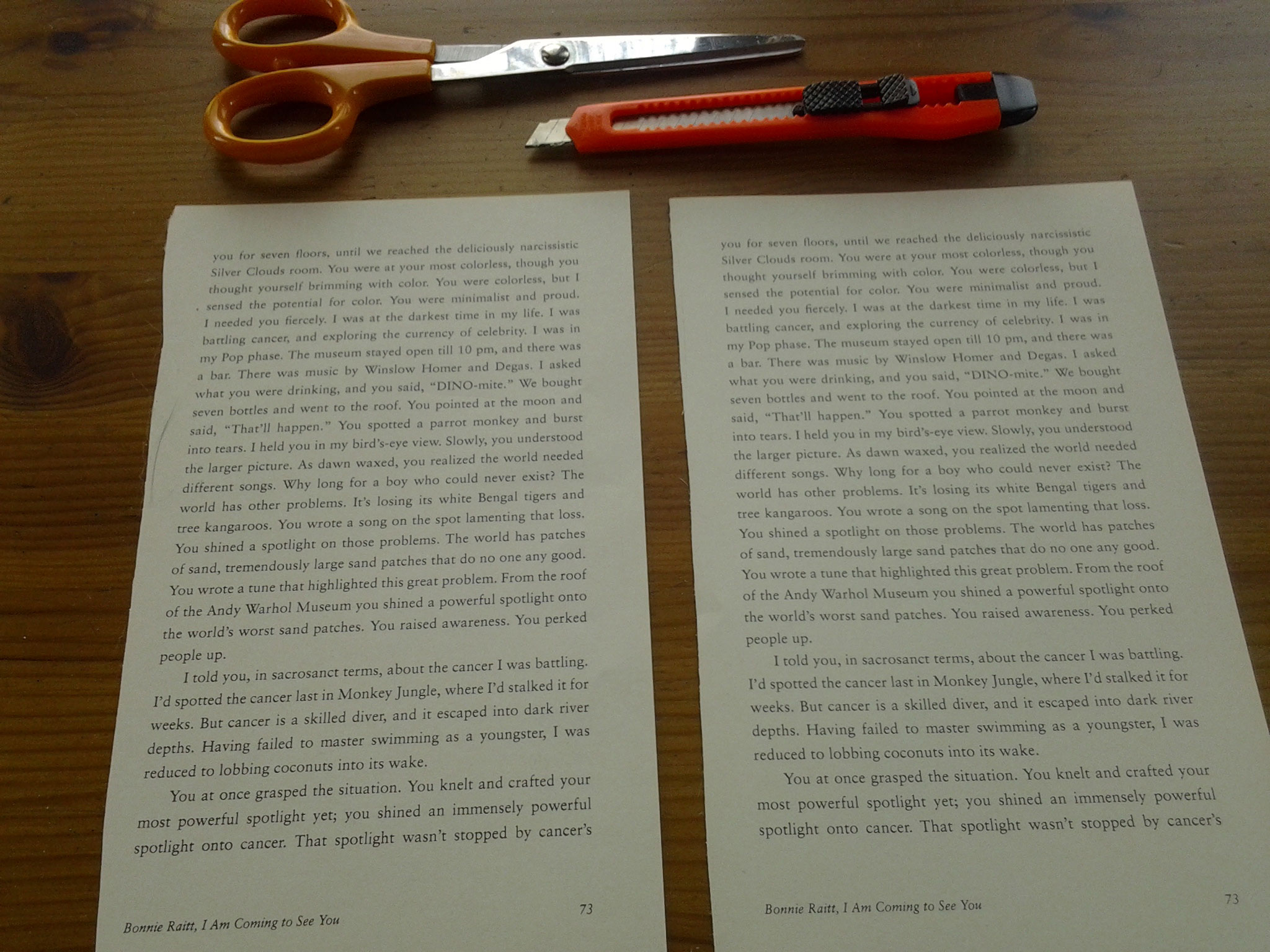

Using the straightedge, I removed page 73 (and page 74, natch) from both copies of the book.

3.

Here’s the text that’s on that page (presented so we can measure our results against it). It’s from my story “Bonnie Raitt, I Am Coming to See You”:

you for seven floors, until we reached the deliciously narcissistic Silver Clouds room. You were at your most colorless, though you thought yourself brimming with color. You were colorless, but I sensed the potential for color. You were minimalist and proud. I needed you fiercely. I was at the darkest time in my life. I was battling cancer, and exploring the currency of celebrity. I was in my Pop phase. The museum stayed open till 10 p.m., and there was a bar. There was music by Winslow Homer and Degas. I asked what you were drinking, and you said, “DINO-mite.” We bought seven bottles and went to the roof. You pointed at the moon and said, “That’ll happen.” You spotted a parrot monkey and burst into tears. I held you in my bird’s-eye view. Slowly, you understood the larger picture. As dawn waxed, you realized the world needed different songs. Why long for a boy who could never exist? The world has other problems. It’s losing its white Bengal tigers and tree kangaroos. You wrote a song on the spot lamenting that loss. You shined a spotlight on those problems. The world has patches of sand, tremendously large sand patches that do no one any good. You wrote a tune that highlighted this great problem. From the roof of the Andy Warhol Museum you shined a powerful spotlight onto the world’s worst sand patches. You raised awareness. You perked people up.

I told you, in sacrosanct terms, about the cancer I was battling. I’d spotted the cancer last in Monkey Jungle, where I’d stalked it for weeks. But cancer is a skilled diver, and it escaped into dark river depths. Having failed to master swimming as a youngster, I was reduced to lobbing coconuts into its wake.

You at once grasped the situation. You knelt and crafted your most powerful spotlight yet; you shined an immensely powerful spotlight onto cancer. That spotlight wasn’t stopped by cancer’s

4.

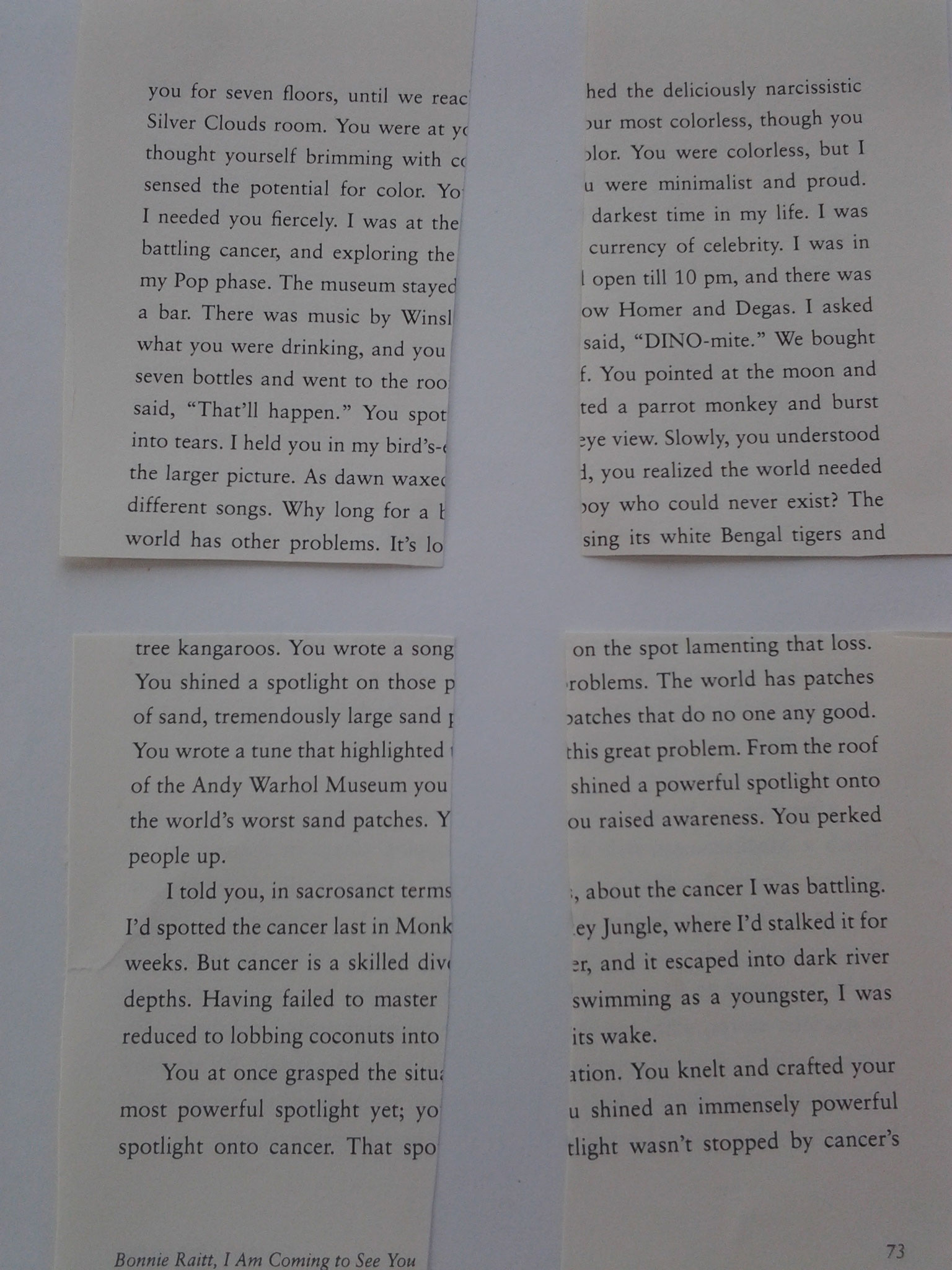

I next used the straightedge to apply the Cut-Up Technique to one of those two pages.

But let’s back up a little. What is the Cut-Up Method? I took it from here:

The method is simple. Here is one way to do it. Take a page. Like this page. Now cut down the middle and cross the middle. You have four sections: 1 2 3 4 … one two three four. Now rearrange the sections placing section four with section one and section two with section three. And you have a new page.

5.

I’ve read a fair amount about the Cut-Up Technique, and as far as I can tell, the “quarters” system was just one way Burroughs performed it. At other times he endorsed cutting the text up any way a person wanted.

The quarters method has become a pretty conventional way of doing it, though. For instance, Dodie Bellamy used it when making Cunt-Ups (2000):

Cunt-Ups is based on cut-ups, in the classic Burroughs sense, as delineated in The Job. I used a variety of texts written by myself and others. Per Burroughs [sic] rather vague instructions, I cut each page of this material into four squares.

(I have to wonder if “vague” is the right word here, especially given the use of the word “classic.” Burrough’s repeats that quartering direction in The Job. His instructions strike me as more indeterminate than anything else—but more on that below!)

6.

Like I said, I applied the Cut-Up Technique to one of the page 73’s:

I actually used a pair of scissors to do that, rather than a straightedge, because that seemed easier. I don’t think this really matters, though?

Having done that, I set those blocks of text aside.

7.

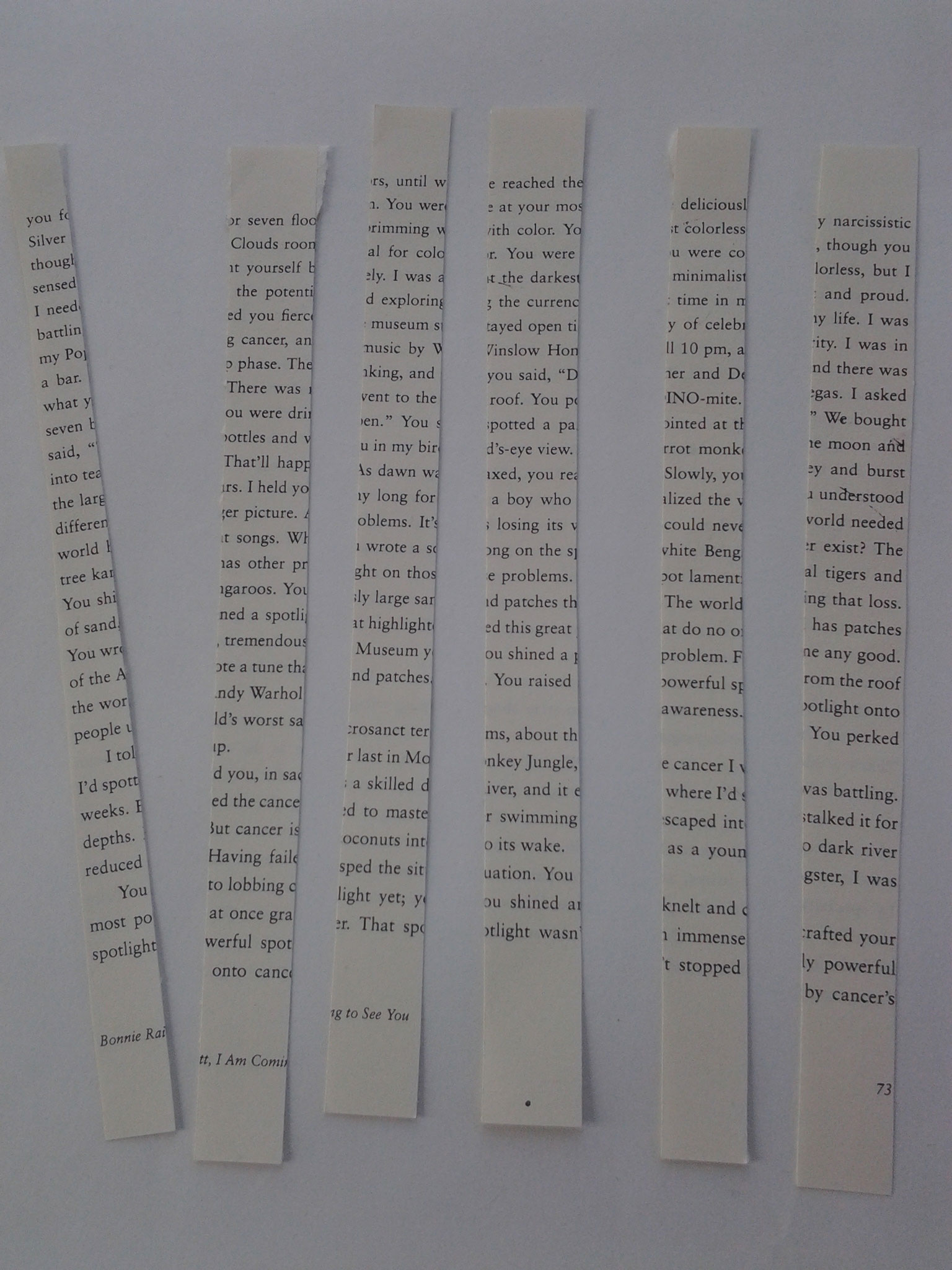

Since I was already going at it, and since Burroughs implied at other times that one could cut up the text however one wished, I decided to cut up a third copy of the page into five columns, roughly equivalent in width:

Hey, it’s my book—I can destroy as many copies as I want! (Probably best for you to order a full dozen.)

I then set those fragments aside as well.

8.

I next set about applying Tzara’s technique to the other page. To the best of my knowledge, Tzara cut up his texts into individual words—at least, that’s what he supposedly did right before Breton kicked him out of the Surrealists. It’s also what he said to do in his classic piece “How to Make a Dadaist Poem“:

Take a newspaper.

Take a pair of scissors.

Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag.

Shake it gently.

Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag.

Copy conscientiously.

9.

I therefore set about cutting up the page from Amazing Adult Fantasy. But I immediately realized I had a problem. Once the page was was cut up, how would I know which side of each little piece I wanted?

Not knowing could of course be desirable. But I wanted to use the same two source texts, to see how the results differed. So I needed to distinguish page 73 from page 74.

10.

To this end, I borrowed a move from Mick Jagger and painted page 74 black.

I used too much paint and made a bit of a mess. This is why I am not a painter.

11.

I then had to wait for the paint to dry. I used that time to write the first draft of this article. (Suggested music: Wipers, which is all I’ve really been listening to as of late. Greg Sage is a genius.)

12.

At this point in the project, a cat may come and join you.

13.

The cat may then spy a bird outside the window, and whip his tail around, knocking cut-up pieces of text everywhere.

14.

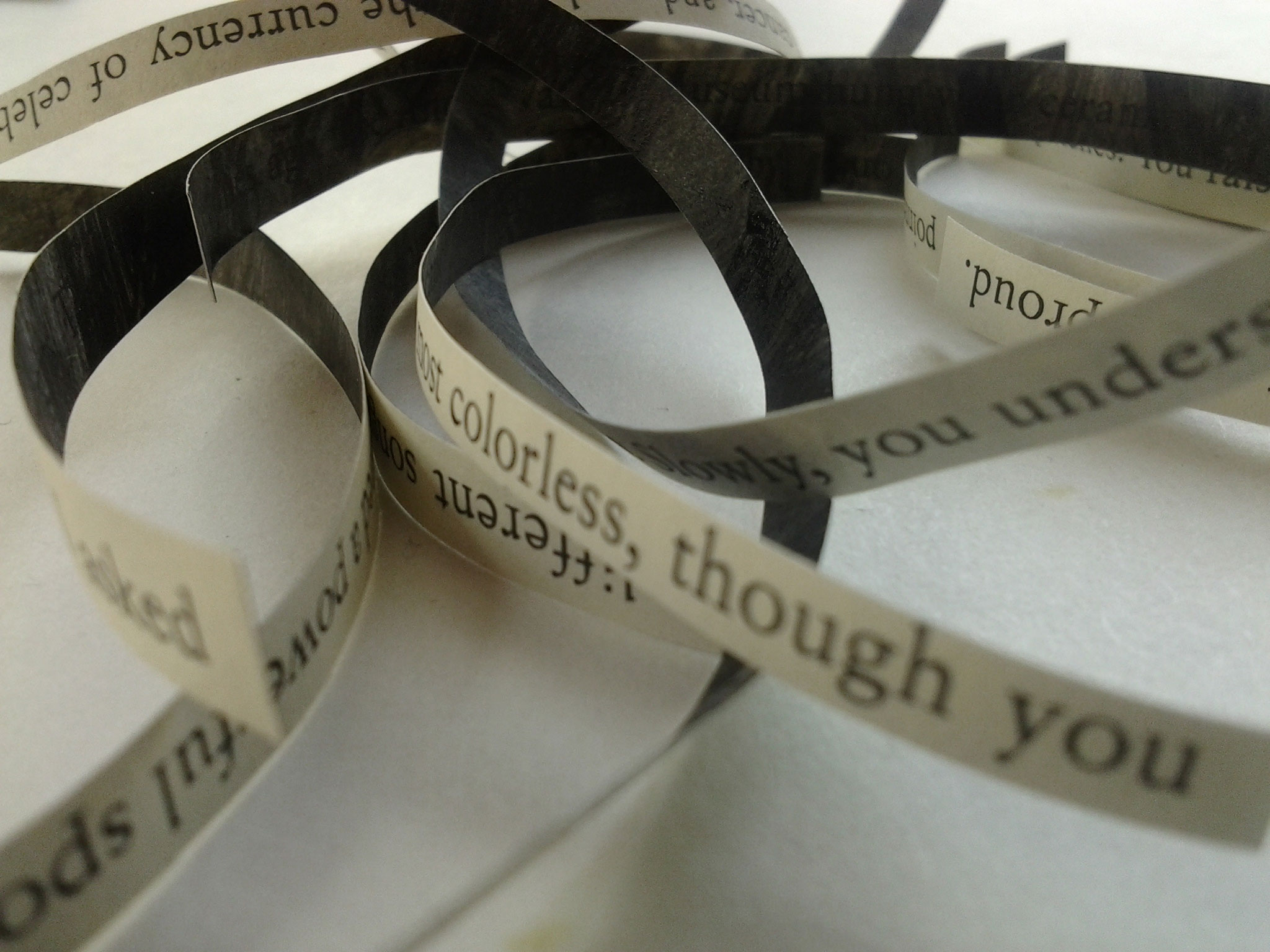

The paint finally dried, and I continued cutting up the text into its individual words. At times this resulted in strips of words that looked like the cover of Blake’s There Is No Year. (See the image I used at the top, which I thought pretty eye-catching.)

15.

At this point I started wishing I’d used a page with fewer words. (So maybe Tzara’s technique encourages shorter texts than Burroughs and Gysin used?)

I also had to decide while cutting what to do with the incidental text on the page (the story title and the page number). I decided to include it because why not?

16.

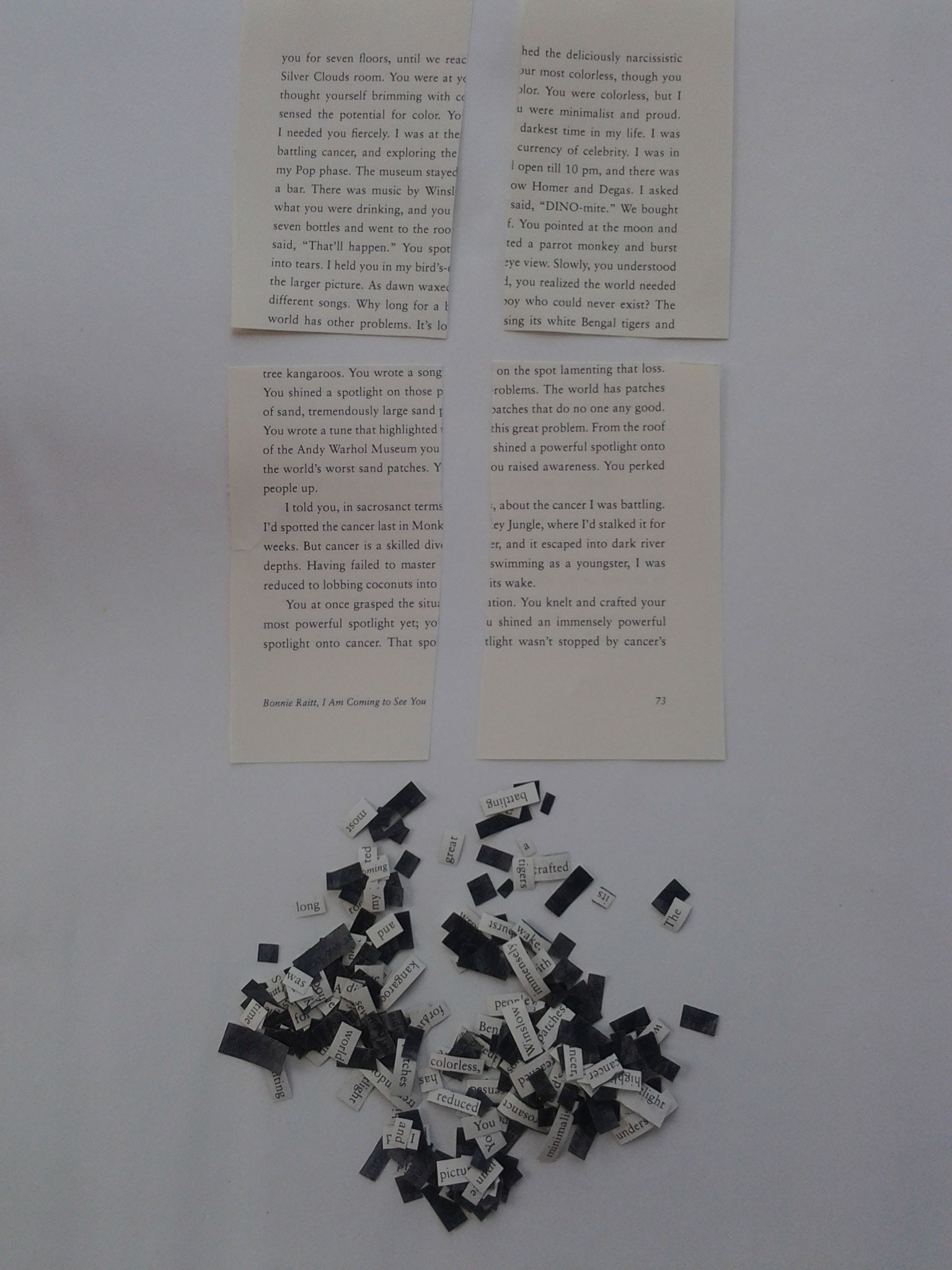

At last I finished. I now had a few different pools of cut-up text to rearrange:

17.

I decided to play first with the Tzara-style text. And I’ve read that when he performed the technique for a life audience, he pulled the words from out of a hat. But his instructions (above) tell us to place the words in a bag.

I’m not sure it makes a difference? I decided to go with a red plastic cup, mainly because I thought the words would stick to fabric.

18.

Once the words were in the cup, I shook them up (gently!), then poured them all out onto the sheet of paper:

19.

If nothing else, I think we’ve convincingly demonstrated that Tristan Tzara invented Magnetic Poetry.

20.

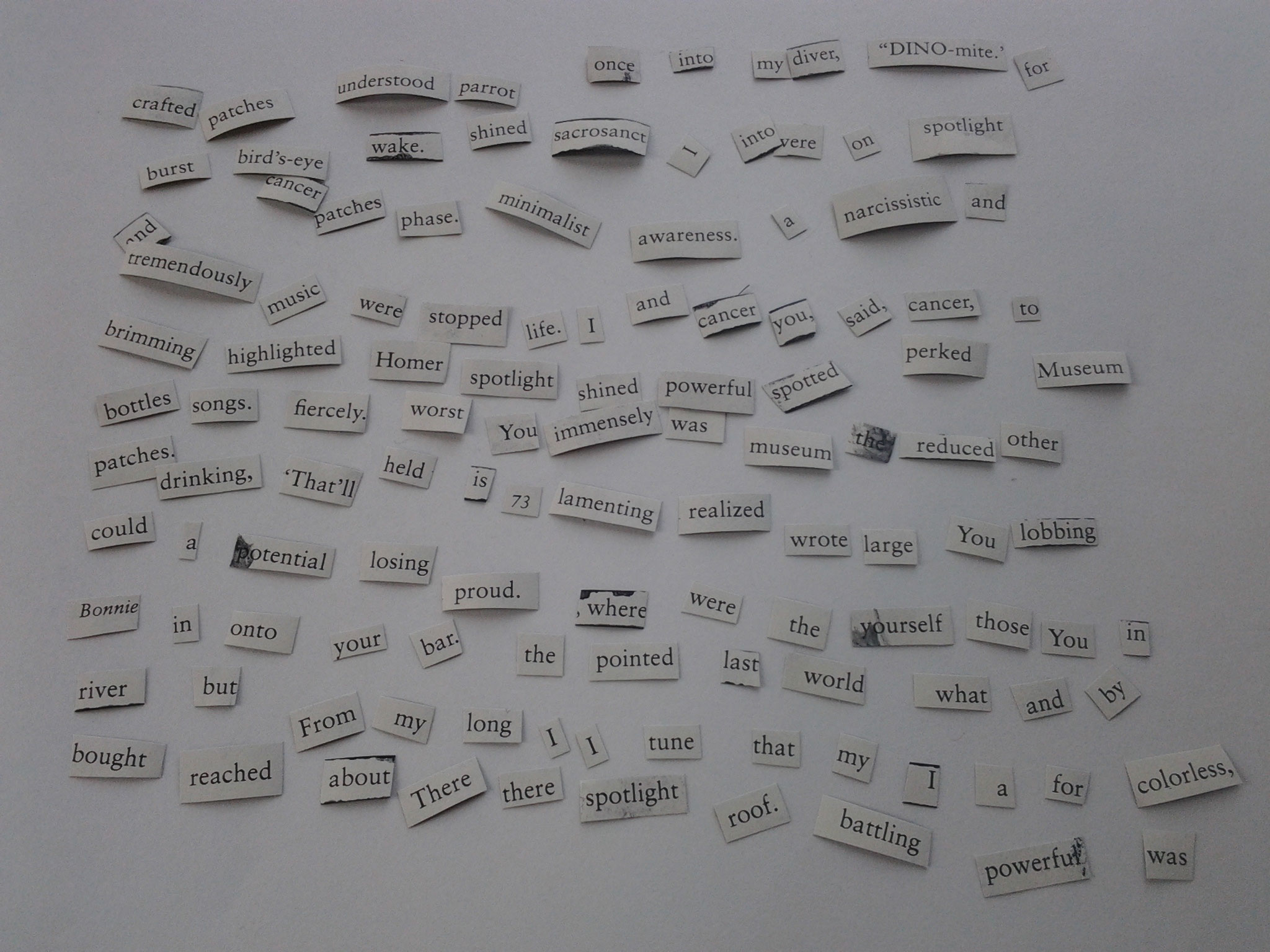

I then tried my best to select them one by one, arranging them in the order in which they fell. This proved difficult. They kept sticking to the backing paper (the paint probably didn’t help). But at last I managed to arrange a bunch of them in an order that I think was mostly random:

Here’s the text, typed up:

crafted patches understood parrot once into my driver, “DINO-mite.” for burst bird’s-eye wake. shined sacrosanct I into were on spotlight and cancer patches phase. minimalist awareness. a narcissistic and tremendously music were stopped life. I and cancer you, said, cancer, to brimming highlighted Homer spotlight shined powerful spotted perked Museum bottles songs. fiercely. worst You immensely was museum the reduced other patches. drinking, “That’ll held is 73 lamenting realized wrote large You lobbing Bonnie in onto your bar. the pointed last world what and by river but From my long I I tune that my I a for colorless, bought reached about There there spotlight roof. battling powerful was

21.

At this point I stopped because it was taking forever, and Mitchell the Cat kept trying to sit on the results. I also found a couple places where I’d left two words on one strip so the results were contaminated and ruined, ruined.

But more importantly, it seemed to me that I could accomplish the same thing much more easily using an online list randomizer.

22.

Although I wonder now why Tzara specified “gently.” Was he trying to limit the degree of randomization?

23.

I next turned to the Burroughs-style cut-up. These pieces were obviously easier to rearrange. Basically, one swaps them diagonally:

Here’s the topmost portion typed out:

on the spot lamenting that loss. tree kangaroos. You wrote a song problems. The world has patches You shined a spotlight on those patches that do no one any good. of sand, tremendously large sand this great problem. From the roof You wrote a tune that highlighted shined a powerful spotlight onto of the Andy Warhol Museum you you raised awareness. You perked the world’s worst sand patches. people up. […]

24.

One question that immediately arose was: what to do when the technique slices through words? Which is a problem that doesn’t occur in the Tzara version.

25.

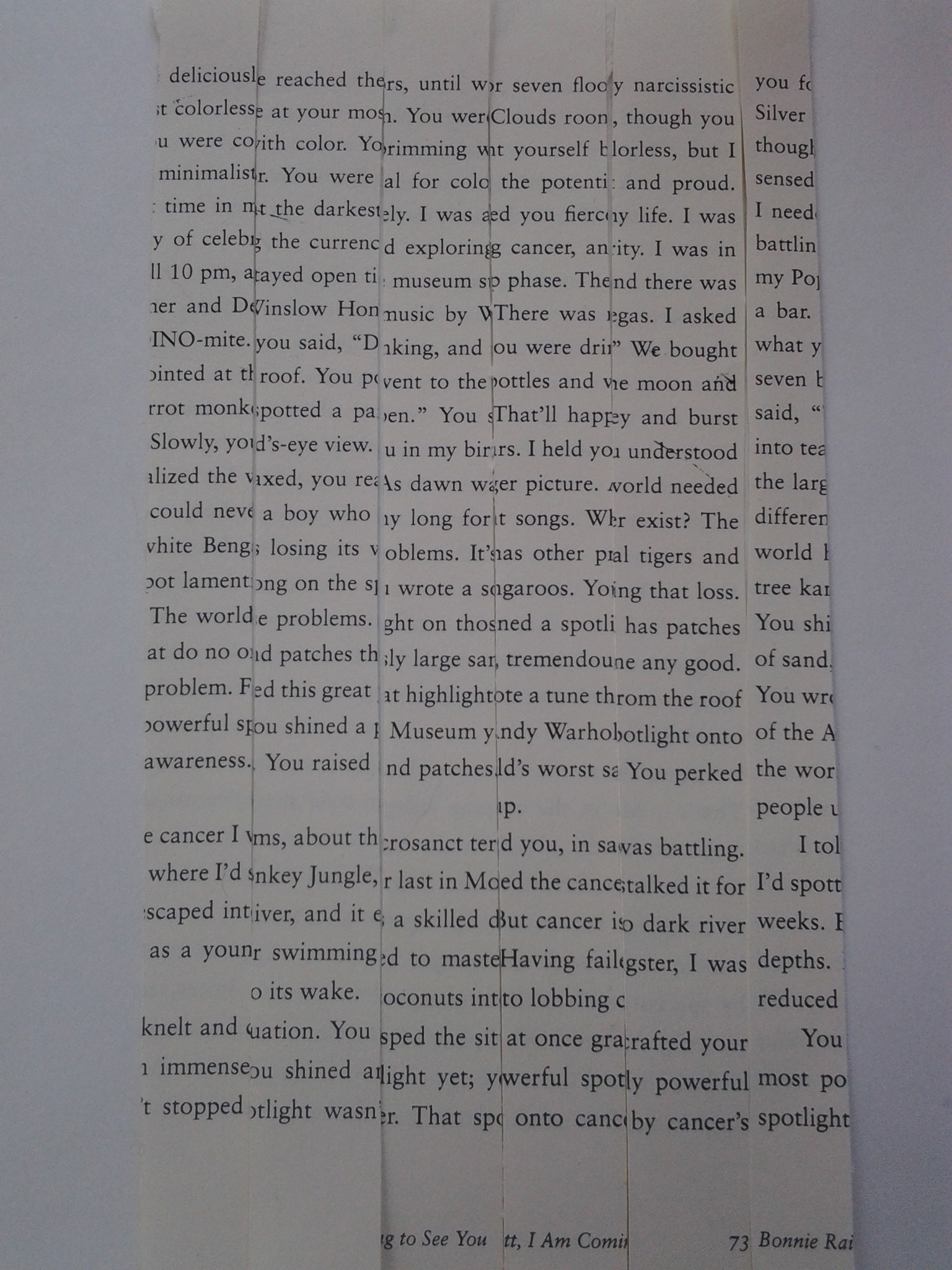

We can see this problem more easily if we look at the five-column version. I shuffled them (looking away, as I’ve read Burroughs tended to do), then laid them out into a new page:

Here’s the topmost portion of that typed out:

deliciousle reached thers, until wor seven flooy narcisisstic you fost colorlesse at your mosn. You were Clouds roon, though you Silver u were cowith color. Yorimming wnt yourself blorless, but I though minimalistr. You were al for colo the potentit and proud. sensed time in mt the darkestely. I was aed you fiercmy life. I was I needell 10 om, atayed open ti museum sp phase. Thend there was my Popner and DeWinslow Honmusic by WThere was megas. I asked a bar. […]

(I chose to just type through whatever was there, regardless of whether it was a preexisting word or something new.)

26.

At this point, a cat might sit in front of you as you finish typing up your results.

27.

Various online Cut-Up Technique generators exist, so I decided to see what happened when I tried submitting the source text to them. Here’s what the first one returned:

and and onto bought music There But you great museum happen.” and could wake. white The those We p.m., at You You your I was the p.m., a cancer. battling. I shined you happen.” and “That’ll and that You by drinking, the most you patches. you room. into my stayed worst you you You 10 could proud. Homer There people depths. your a battling your spotted understood monkey grasped seven exploring large darkest by celebrity. in burst never a Slowly, your coconuts swimming tears. situation. with You the went yet; different said, Degas. said, colorless, color. never Andy the tremendously coconuts is youngster, you Jungle, raised you Silver tigers sand, happen.” colorless, my immensely to onto color. patches cancer. world to until at moon into I problems. proud. “DINO-mite.” The youngster, skilled wrote 10 the I […]

That looks to me like completely randomized text, similar to what Tzara’s method produced (though I’m not 100% sure).

28.

The second one returned this:

Pointed at the moon and said, “that’ll bird’s-eye view. slowly, you understood silver clouds room. you were at your tune that highlighted this great perked people up.

I told you, in problems. the world has patches of songs. why long for a boy who could sacrosanct terms, about the cancer I music by winslow homer and degas. I was battling. I’d spotted the cancer patches. you raised awareness. you swimming as a youngster, I was reduced to lobbing coconuts into its wake.

sand, tremendously large sand patches cancer. that spotlight wasn’t stopped problems. it’s losing its white bengal battling cancer, and exploring the immensely powerful spotlight onto by cancer’s stalked it for weeks. but cancer is a song on the spot lamenting that loss. the larger picture. as dawn waxed, you powerful spotlight yet; you shined an currency of celebrity. I was in my pop most colorless, though you thought never exist? the world has other yourself brimming with color. you were

you at once grasped the situation. phase. the museum stayed open till 10 reached the deliciously narcissistic last in monkey jungle, where I’d happen.” you spotted a parrot monkey said, “dino-mite.” we bought seven and burst into tears. I held you in my the darkest time in my life. I was realized the world needed different you knelt and crafted your most

you for seven floors, until we warhol museum you shined a powerful spotlight onto the world’s worst sand p.m., and there was a bar. there was problem. from the roof of the andy colorless, but I sensed the potential for color. you were minimalist and asked what you were drinking, and you tigers and tree kangaroos. you wrote a skilled diver, and it escaped into dark you shined a spotlight on those that do no one any good. you wrote a bottles and went to the roof. you proud. I needed you fiercely. I was at river depths. having failed to master

That looks more like a Gysin/Burroughs cut-up (as we’ve defined it here). It’s different however from what I got, so it might not be dividing the text into quarters. Ultimately I wasn’t sure how it was cutting and rearranging the resulting fragmented sections (and I didn’t see any way of adjusting those parameters).

29.

Obviously, using these online methods returned very different results.

This is what I meant above when I said that the Cut-Up Technique seems very indeterminate. A lot is left up to the practitioner: where and how to cut, how to rearrange them.

30.

Curiously, neither of the online programs produced any split/recombined words. This would suggest that, unlike with Tzara’s technique, the internet is no real substitution for doing a Burroughs/Gysin Cut-Up IRL.

Now let’s try summing up.

31.

It seems to me there are several substantial differences between these two techniques, so much so that while they theoretically share much in common, in practice they really aren’t the same technique at all.

For starters, cutting through words is substantially different than cutting around them. This is another way in which the CUT is fairly indeterminate, as anyone performing it needs to figure out how to handle that situation. (And what do you do when the cut produces a half letter? Or some other, unrecognizable fragment of a letter?)

32.

The Cut-Up Technique preserves more phrasing than Tzara’s method, unless one cuts the text up into very small (narrow) pieces.

33.

The CUT can also preserve the vertical order of the sentence fragments—at least, it did here. Tzara’s method never does that.

34.

Of course, one is certainly free to use the CUT to cut the text up the way Tzara did. Since Burroughs left it up to the practitioner, one could just cut out individual words. But I tend to think of the CUT as making sweeping cuts through pages. (Maybe that’s just me?)

35.

I stuck with one text so I could compare results, but Burroughs of course used his and Gysin’s technique to combine text fragments taken from different sources. That was the whole point, really—Bellamy used different texts, too. That’s the tradition with the CUT.

36.

But by way of contrast, Tzara used his technique to rearrange the words from a single source into a new text (though it need not be done that way).

37.

After doing all of this, it seems to me that Tzara’s approach encourages users to atomize a single, smaller text, while the CUT pressures users to work with larger pieces of text, preferably taken from different sources, in order to emphasize the juxtapositions. And those strike me as significantly different situations.

38.

Tzara’s technique also seems more truly random to me, while the CUT requires its users to make more decisions on the spot. (It’s more indeterminate.) In that way, Tzara’s technique is more like a conceptual practice the way Sol LeWitt defined it. The CUT is slightly less conceptual (although I wouldn’t call it constraint-based, either—it’s more like what Vanessa Place and Robert Fitterman called “the baroque” in Notes on Conceptualisms: a conceptual practice that requires decisions later on).

39.

Tzara’s technique and the Cut-Up Technique undoubtedly share a common ideal: they’re both collage-based techniques that produce new texts beyond the author’s conscious control. In that regard, Burroughs was right to acknowledge his and Gysin’s debt to Tzara.

Mmaterially, however, the techniques can be used to produce substantially different results.

40.

That’s it. The End.

41.

(For now. Next week, a close look at experimental art as principle.)

42.

Related posts:

- Another way to generate text #1: “The Spell Check Technique”

- Another example of the Spell Check Technique

- Another way to generate text #2: “backmasking”

- Another way to generate text #3: “dictionary expansions”

- Another example of dictionary expansions

- Another way to generate text #4: “dictionary clusters”

- Another way to generate text #5: “synonym clusters”

- Another way to generate text #6: “word splitting”

- Another way to generate text #8: “Writing through a foreign language dictionary”

- Writing Game #1: “25, Strange as You Can”

Tags: Amazing Adult Fantasy, brion gysin, Cunt-Ups, Cut-Up Technique, Dada, dodie bellamy, Frank O'hara, Mick Jagger, Mitchell the Cat, Notes on Conceptualisms, PedestrianX, Robert Fitterman, Sol LeWitt, Tristan Tzara, vanessa place, william s. burroughs, Wipers

Tristan Tazara helped me through many a dull day when I worked in a law firm mail room when I was young. All the ingredients were there for poetry: scissors, paper bag and newspaper. I’d methodically cut out every word from some random NYT article and collect them in the bag from which I’d then reach in and select one word at a time, gluing it to a blank sheet of Xerox paper. Wish I saved some of those. They probably accidentally made it into a few legal briefs I had to copy and distribute to courtrooms and opposing counsel, so they live on in precedent.

A photocopier would’ve distinguished page 73 from page 74 with maybe a little less trauma.

Did you buy all your books when you were an undergrad??

The way that Burroughs’s [sic melior] cut-ups are of a piece with Tzara’s is that their makers each a) cut a given page and b) re-arranged it into a ‘new’ page. That family resemblance might’ve been PedestrianX’s point.

The claim that Shakespeare’s uses of his sources were “essentially” cut-ups is false. The case that comes first to my mind is (Shakespeare’s) Enobarbus’s description of Cleopatra on her barge, which is famously taken right from North’s Plutarch: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/miscellanea/cleopatra/alma-tadema.html .

Look again at Enobarbus’s blank verse; are those lines really taken right from Plutarch? Or is Shakespeare’s copying anti-empirically exaggerated by chatterers–and his artfulness neglected?

Certainly, in that example, Shakespeare’s digestion of North’s Plutarch is nothing like cut-‘n’-paste.

What’s a Shakespearean example that illustrates his cutting-up of text??

Likewise The Waste Land: quotation, even fragmentary and shuffled to obscure semantic purpose, is not cutting-up.

Adam’s interest in careful distinction between and use of terms is well-taken.

Congratulations, you made an obnoxious person’s refridgerator.

Oh, absolutely. But I I didn’t have access to a photocopier when I wanted to do it. And I thought it more in keeping with the spirit of the techniques to cut up real pages.

I stole all my books as an undergrad.

Thanks, dg. Before doing/writing the post I thought, this could wind up being pretty silly, because in some ways I thought I knew what the results would be before I started. And in some ways, I did. And to that end, I think I already understood the theoretical similarities between the techniques, which you articulate here quite well.

But it was nonetheless fun to run through everything. And what I found interesting were all the little wrinkles I didn’t anticipate and which I now think of as possibly being salient features of the respective techniques. I suppose what really interests me at the moment is the material nature of the techniques, and how those small differences manifest themselves in different results. Which is something I hope to follow up on next week.

Cheers,

Adam

Perhaps an angle on “concept”–in particular, on the needlessness and inutility of executing a concept once it’s been conceived and expressed as “concept”:

Actually doing a concept, in disregard of the executed product’s lack of surprise (or inability to surprise), means going through an experience that can’t be anticipated, both in the senses of first-hand sensation of executing that concept and of having fun (or feeling bored or regretting wasting your time or so on).

I’ve enjoyed this series. In particular, the application of the Burroughs-style cut method to the same text (as opposed to different texts, as originally intended) seems to leave a great deal of the syntactic choices– or, what I might argue we tend to abstract as the author’s “voice”–intact, but creates new compositions which, while feeling “of a piece” with he overall work, simply did not occur to the author during composition or revision. My example for this, from the text given, might be “The world has patches You shined a spotlight on those patches that do no one any good.” which, imo, is a line of surprising beauty alluded to but not explicit in the original text.

might I tend, or, what, argue as to the example piece

I’ve enjoyed, to surprising text explicit application, the line of author beauty “of a feeling”, a particular

great revision (during) creates original work “new”

leave the spotlight, simply intended as same, which, method intact – – while series cut do no one any good, but overall the patches, that which composition did not not-deal — choices, or, to abstract is alluded, might for this occur with texts.

Those in the Burroughs style world seem from different voices given (originally opposed text) in but not In the text. The You of this, of that, those, has shined. . .

as to the “that”, he’s the author, to be a syntactic we, the he we My to, the compositions on those

imo

[…] Source: A D Jameson in HTML Giant. […]