Let’s overanalyze to death … Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart”

So far in this very irregular series, we’ve scrutinized Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used to Know” and Macaulay Culkin eating a slice of pizza—preparation for tackling one of the greatest and most beguiling music videos ever made.

“Total Eclipse of the Heart” was a single from Bonnie Tyler’s fifth album, Faster Than the Speed of Night (1983), and her biggest hit. It was written by Jim Steinman, Meat Loaf’s once and future collaborator. Steinman also planned out the video, which was then directed by Russell Mulcahy, a man responsible for numerous ’70s and ’80s music videos, as well as the films Highlander, Highlander II: The Quickening, and Blue Ice. So that’s the aesthetic world we’re dwelling in. (In a single word: overblown.)

The video itself is pretty broad, and rather easy to read—broadly. Simply put, Tyler plays an instructor (or an administrator) at an all-boys boarding school. (I will refer to her character as “Tyler” throughout, for convenience’ sake.) Extremely sexually repressed, Tyler endures a long night of the soul fantasizing about her young charges; this constitutes the bulk of the video. Come morning, she (and we) are returned to restrained, repressive reality. But we’re left with the hint that A.) at least one of her students has magically become aware of her fantasy, or B.) her fantasia has caused Tyler to become mentally unhinged. (I lean toward B and will defend that reading below.)

That’s the basic outline. The devil, however, sits in a straight-backed chair, clutching a dove. He’s also in the details, so let’s delve deeper …

Here is the copy of the video I’ll be working with; it’s 5 minutes and 33 seconds long. The album version is over seven minutes long, and there’s also a shorter version of the video/single, clocking in around 4:33 (very John Cage). It’s sometimes up at YouTube and sometimes not; the main difference is that it omits the second half of the first verse, jumping instead right to the chorus.

Let’s begin by dividing the video into four overall parts:

- Tyler by herself (0:00–0:50)

- Fantasy 1 (0:51–2:58)

- Fantasy 2 (2:59–4:40)

- Coda (daytime) (4:41–5:33)

What’s going on here?

1. Tyler by herself (0:00–0:50)

It’s the middle of night and Tyler’s alone and lonely—the lyrics tell us so:

Turn around, every now and then I get a little bit lonely and you’re never coming round

Her setting is certainly romantic: she’s surrounded by candles and billowing curtains, and there’s a full moon outside. So far, we seem to be in an anonymous Gothic fantasy-land common to music videos, especially ones from the early 1980s.

Gradually, however, we realize that the setting, far from being metaphorical, is literal: we’re in a private school. (It also happens to be, in real life, Holloway Sanatorium, a mental institution.) Tyler is a teacher there (in the chemistry department, perhaps?), and she enjoys mooning about after hours in a tight white gown, lighting candles and opening windows. Her outfit marks her as virginal and repressed—not unlike pop culture’s then-reigning queen, Princess Leia.

The first hint that we’re dealing with anything stranger than insomnia comes early, but stands alone for now; it is of course the shot of the dove flying in through the open door (0:16–0:19):

A few comments here. The poor bird is struggling to fly, flapping about at the bottom of the screen. What should be a romantic image, then—soaring and dreamy—is in fact a frustrated one. Would it be gauche to call it a symbol of Tyler’s own frustrated desire? I hope not, because that’s totally what it is.

Tyler continues mooning about. And despite the woman’s solitude and the relative sense of calm, the song’s structure suggest that she’s hiding or ignoring something. A male voice keeps singing, “Turn around”—indeed, those are the first words we hear. And the more that voice repeats, growing increasingly insistent, the stronger our impression that Tyler is refusing to confront something.

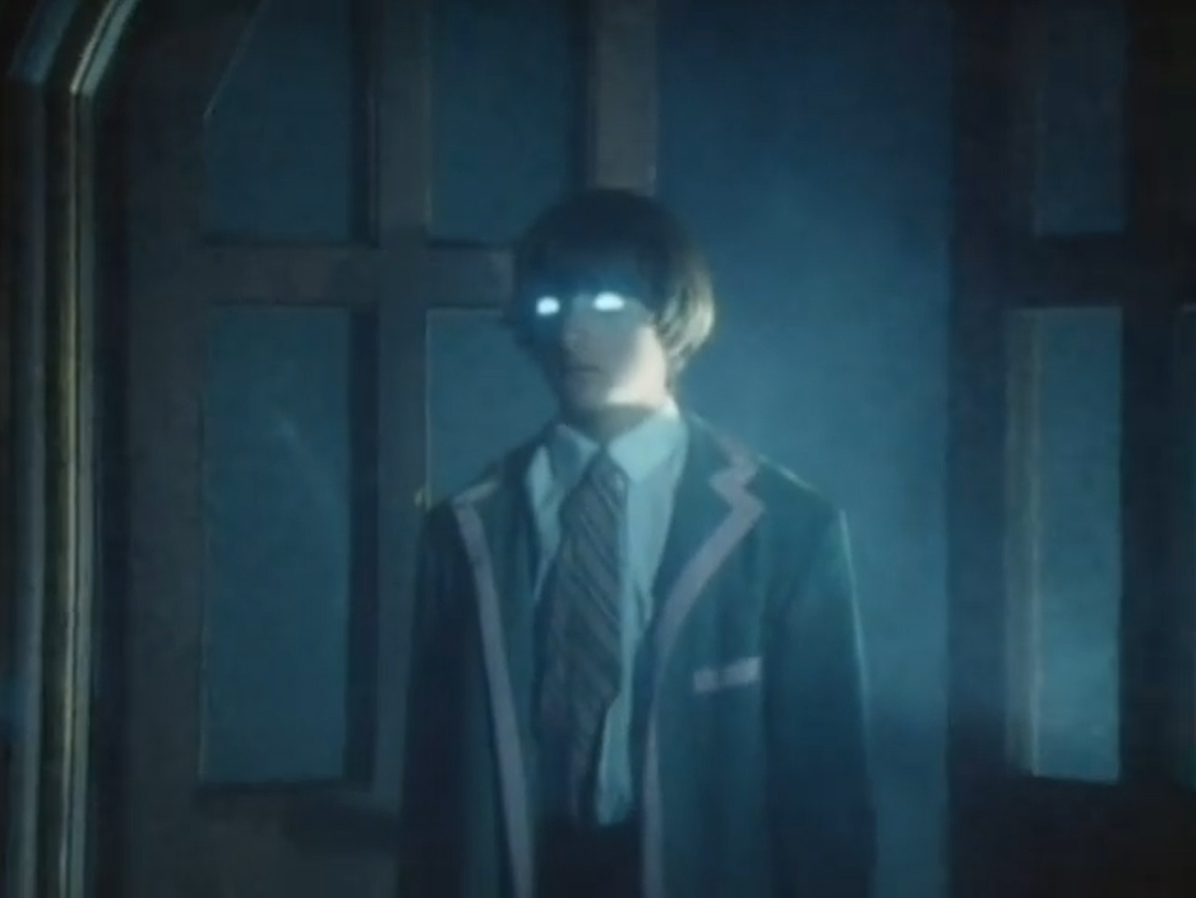

Her reverie is interrupted around a half-minute in, when a student enters the school, presumably through its front doors. But pay close attention to how this actually happens. At 0:37, a car passes by the school, its twin headlights shining through the door:

Only after this does the student actually enter, his glowing eyes matching the headlights (0:44–0:46):

What’s happening here, I’d argue, is that Tyler has become so lost in her wanting that she’s mistaken a passing car for a student—that obscure object of her desire. She runs with this flight of fancy, imagining that a handsome young man is in fact paying her a visit. It’s significant that he’s entering from outside: Tyler’s insular, academic world, in which white doves struggle to fly from room to room, is now being invaded by an external force.

The young man’s eerie gaze is immediately identified with Tyler’s: we cross-dissolve from him to her, and for a moment (0:46) his glowing eyes are overlaid over her left eye:

This connection is emphasized by the lyrics at that point (“Turn around, bright eyes”).

Let’s pause to consider the glowing eye imagery, since it plays a significant role in both the lyrics and the video. (Recall also that the song’s writer, Jim Steinman, planned the video, so the connections between words and image are very much intended.)

Glowing eyes are a common enough motif in mythology and folklore, where they usually indicate an especially penetrating glare, some kind of magical “sight beyond sight.” This motif is common, too, in popular culture: the villain Sauron in the Lord of the Rings is characterized as a giant fiery eye that sees all, and the mutant telepathic children in the 1960 feature Village of the Damned (an obvious inspiration for this video) are distinguished by their disturbing glowing eyes:

The horrific subjects of Children of the Damned, just like the male students in this music video, dress impeccably nearly and behave with a disturbing cold politeness. This pairing occurs a lot in pop culture—for instance, it showed up again just last year, in The World’s End:

Anyway, at this point in the video, just shy of a minute in, Tyler’s fantasy has been acknowledged by a student (real or imagined). She’s been seen wanting—she’s been acknowledged. And just like in The Children of the Damned and The World’s End, once a single student can see her frustrated longing for what it is, the knowledge quickly spreads to the others, who share some kind of telepathic connection, or hive mind.

But this recognition, far from embarrassing or paralyzing Tyler, enables her to reveal her desire openly, a shift that motivates the remainder of the video.

2. Fantasy 1 (0:51–2:58)

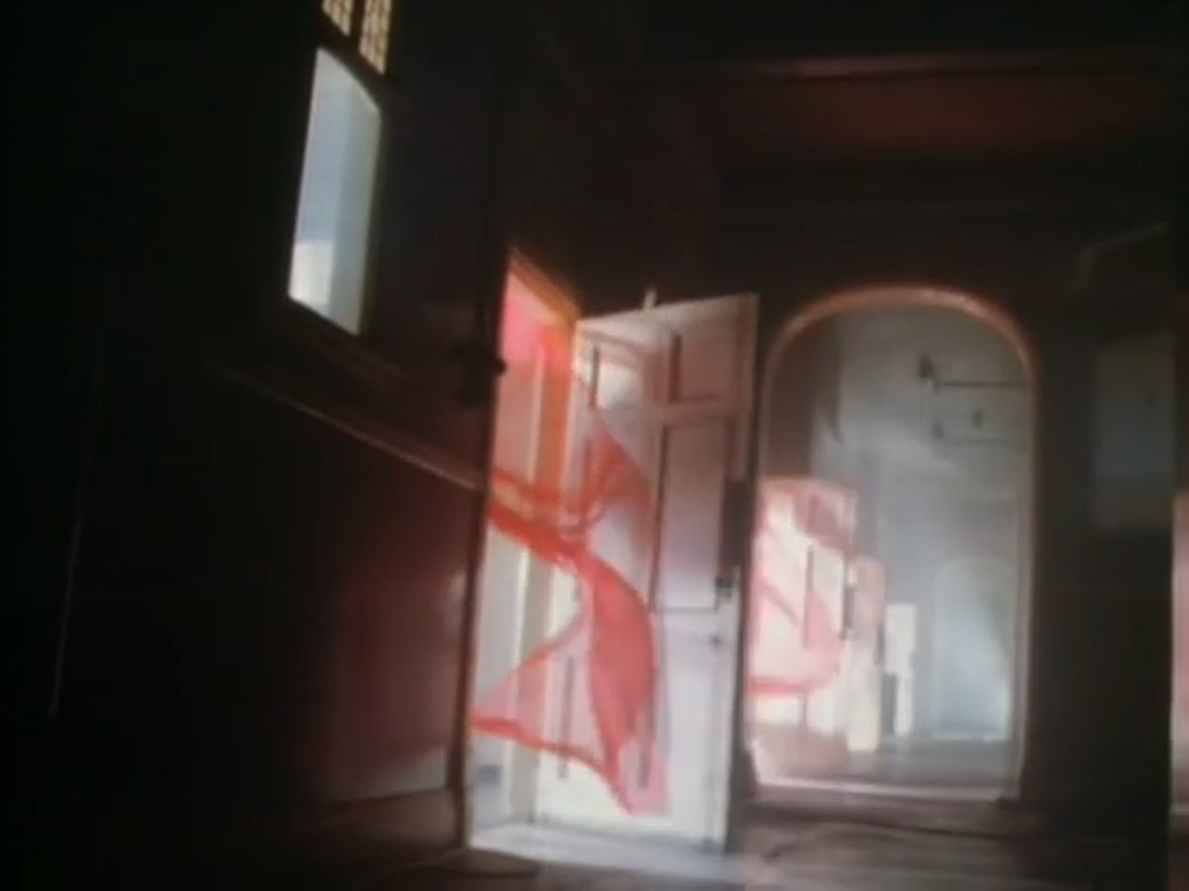

This part kicks off with a shot of doors blowing open (matched by a kick to a bass drum in the song). Red curtains billow in, suggesting that boundaries are breaking down. The shot also suggests penetration, and the loss of virginity.

Tyler leaves her lonely chamber for more colorful environs. She wanders the school’s corridors, and note how the first thing she does is peer through an open door—a door rather like the one that the dove struggled to fly through. Beyond the doorway awaits a group of students, who look up to acknowledge both her and us—they look out at the camera, developing the motif of supernatural sight (0:55). (There’s a bright white light behind the students, about which I’ll have more to say later.) We see them from Tyler’s point of view—from this point on, we are directly associated with, and implicated in, her fantasia. Which makes sense: we’re definitely tagging along for the ride, enjoying her fantasy with her.

The dove, meanwhile, has somehow ended up in the hands of what appears to be a young demon or angel (or both), sitting in a room with other doves (they’re in the shot’s background, perched on a windowsill). He throws the one he’s holding toward Tyler (1:04–1:10):

This might be how the first dove ended up going through the door, struggling to stay aloft. (And in a metatextual sense, this is true: in making the video, some handler no doubt threw the poor bird to create that image.) This boy is like the other students in that he’s some sort of supernatural being, but he also seems to be something more. It’s worth noting that he’s much younger than the others students we’ve seen—prepubescent—suggesting that Tyler’s desires might be pedophiliac. (More on this in a bit.)

From here, Tyler wanders past a group of boys in swimsuits (1:12–1:14)—

—continuing her erotic fantasy. She presumably spends a fair portion of each school day gazing furtively at her subjects, secretly desiring them. Now she is free to observe them openly—to see them, and be seen seeing.

In the next scene, Tyler wanders into a larger room where some ninjas are dancing (1:16–1:21), one of the video’s more talked about moments:

However, I’d like to argue that this element is extraneous. Unless the private school has some kind of ninja club, these combatants aren’t her students, and as such seem out of place here. I could be wrong about this, mind you—and believe me when I say that I’ve scrutinized this video enough that I’ve almost convinced myself that the kicking ninja in the foreground looks “rather young,” judging by what we can see of his eyes. But there’s a reason why this black-clad trio strikes so many viewers as being so utterly random. (Because it is.) Other attempts to read the martial artists symbolically—”Tyler is wandering into danger!”—come off as corny.

So although these ninjas are undoubtedly cool, and memorable, I read them mainly as an example of early ’80s excess, a trendy image crammed into what is otherwise a meticulously constructed artwork. (Ninjas were well on their way to mass popularity in early ’80s US. The G.I. Joe character Snake-Eyes first appeared in 1982, which is also when Chris Claremont and Frank Miller sent Wolverine to Japan for his four-issue miniseries. And Frank Miller had created the ninja clan The Hand one year earlier, in Daredevil #174.) … If I’m missing something here, by all means let me know, but until then I’ll maintain that the video would be better if this trio were more recognizable as students. (It doesn’t help that these ninjas appear so early on in the video, disrupting the careful progression established so far.)

Right after the ninjas we encounter some young men in formal dress, busy toasting one another around a dinner table (1:22–1:32):

All of this student activity is incongruous—it’s late at night, the kids should be in bed—but this one carries with it the idea of some kind of secret society that meets at midnight when the moon is full. Something is definitely going on.

Following this, we get a series of “athletic” shots—groups of young men fencing, doing gymnastics, and dancing in football gear. These images, I’d argue, accomplish everything the ninjas did, and more:

- They demonstrate the fantastical nature of this particular night. These young men belong in the institution—they’re students—but (as mentioned), it’s improbable that they would be exercising at night. Tyler is instead wandering through the hallways of her own desire, recalling things that she’s seen during the day, but differently. (Her students’ shirts billow open, for instance.)

- They escalate the fantasy. The fencers are properly dressed head-to-toe, but the gymnasts are bare-chested. And then the footballers are similarly bare-chested (and doing something something more akin to modern dance than football). These successive images become increasingly improbable: Tyler is mentally undressing her charges.

Tyler, then, is gradually exploring her heretofore repressed desires. Having ventured out of her chamber on this magical night, she is free wander the school, confronting her daytime desires openly—and having her voyeurism acknowledged.

This section culminates in the entrance of a choreographed pack of “bad boys,” done up in black leather. First, Tyler passes through a door (a recurring sign that matters are escalating) as a white light shines behind her (1:53):

This light is the continuation and magnification of the original headlights/eyesight that penetrated her private chamber and motivated her (and that showed up in the earlier shot, glowing behind the students seated at their desks). As her imagination keeps running further and further afield, growing increasingly dramatic, this knowing light is amplified.

The biker boys are wearing mirrored sunglasses, a nice variation on the “glowing eye” motif (and that also recalls the goggles that the swimsuit-clad boys were wearing). Since these young men, too, have “the sight,” they are able to turn and see Tyler. As before, this is accomplished via a point of view shot, in which the boys stare directly at the camera—and therefore at us (2:04):

But unlike the previous boys, who have only acknowledged Tyler’s stare, this group reaches out toward Tyler (and toward us). They make a rapid clenching motion, which Tyler then repeats herself (although no actual physical contact is made). The stakes are clearly getting higher. Open voyeurism might not prove enough, and some kind of physical contact between Tyler and all these menfolk might be possible.

As if to demonstrate this new stage of desire, Tyler runs toward a pack of the football boys (2:15)—

—only to have them disperse, leaving her to run instead into her own reflection in a mirror (2:16):

The meaning here seems pretty straightforward: all of these boys are but illusions, and any attempt to actually grab them will result only in Tyler grabbing herself. (Ahem.)

This moment, in which Tyler strikes the mirror, initially seems to dispel the accumulating fantasy. Her illusions, to put it succinctly, have been dashed. The mirror provides the return of cold hard reality: Tyler cannot pass through it, like Alice did, or like the characters in Jean Cocteau’s Orphée. She is singing only to herself. She’s alone.

Accordingly, the song grows subdued, as Tyler mournfully summarizes her situation:

Once upon a time I was falling in love

Now I’m only falling apart

There’s nothing I can do

A total eclipse of the heart

Again, the lyrics are well matched to the video. “Once upon a time,” with its fairytale connotations, echoes the idea that, in this case, love is fantastical, unreal, otherworldly. The song’s title and refrain, “total eclipse of the heart,” connects such love with the bright, acknowledging light that keeps flaring up throughout this video. When that light falls into shadow, all love—and all fantasy—is rendered impossible. (What’s more, the title of the album that the song hails from, Faster Than the Speed of Night, paradoxically links light with nighttime, via a rhyming substitution.) Furthermore, when it’s examined in this, uh, light, another line in the song makes more sense:

Your love is like a shadow on me all of the time

Obviously, the preferable situation is for love to be like a light—provided that that light can be withstood.

At this point in the song/video, Tyler seems to have overreached. She tried breaking out of her repression, and exploring her fantasies—only to have them evaporate when she attempted a physical connection. The magical glamor has dissipated (another common fantasy motif).

Tyler runs from the school (2:53). Is she embarrassed? Trying to flee the source of her unrequited passion? Either way, it seems as though the song, the video, and the fantasy are coming to an end.

However, the song rallies here, embarking on a long bridge that grows increasingly wild. But before we analyze that section, pay close attention to the soundtrack as Tyler runs from the school (2:53–2:58). Do my ears deceive me, or does it contain the sound of a car passing? I believe that it does. If so, that’s a clear reference back to the passing headlights that prompted all this phantasmagoria.

And so Tyler’s attempt at escape is defeated, and she is plunged back into fantasy. This time around, however, the fantasy is different—wilder, and darker. Rather than escaping, Tyler has fallen prey to the illusions she summoned earlier.

3. Fantasy 2 (2:59–4:40)

In this section, the video grows much more fantastical (not to mention erotic). Shots of Tyler running through the school’s corridors, her white dress billowing behind her. (Note the point of view shot at 3:00, in which we momentarily take Tyler’s place.) This footage is interspersed with slow-motion shots of:

- a gymnast conducting a flip (3:00);

- a muscular swimmer rising to stare at the camera (3:07);

- students in suits wrecking a banquet table (3:09, 3:13, 3:19—and note the escalating violence);

- a student lifting his fencing mask (3:14);

- another shot of the fencer lifting his mask, this time casing gold to pour down over his face (3:23);

- and, most remarkably, emerging from the billowing output of a smoke machine, a choir of boys with glowing eyes (3:27)—an image that could be straight out of Village of the Damned:

Remember my claim that the character Tyler is portraying is actually a pedophile? The boys are undeniably growing younger. They, like their classmates, stare directly into the camera, an action that will only increase in frequency during the song’s conclusion. (They also pick up the refrain, “Turn around, bright eyes.”) And, quite like the clutchy-feely biker boys, these kids now attempt greater contact with Tyler, as one of the boys lifts up and precariously flies at the camera (3:34):

(Wire-fu would greatly improve in the coming years.) Interestingly, as the child touches down, he seems to be staring at us—out at the camera—rather than at Tyler.

Following this, there’s a sudden push-in on the creepy young boy we saw earlier—the winged Emo Kid who threw Slo-Mo Dove at our face. As the camera rushes in, he raises his head to address it, lip-syncing backing vocals (“And I need you”) (3:43):

A few thoughts here. First, this child is directly associated with the choirboys. They are of similar age, and the push-in shot inversely mirrors the way that the choirboy flew at the camera. His eyes are also emphasized, via makeup.

Things are definitely coming to a head, and growing more confrontational. Accordingly, it’s time to consider the winged elephant in the room—a darker reading of the video. Is it possible that Tyler’s character has actually molested one of her charges? Certainly the lyrics suggest that the love in question is somehow wrong or dangerous:

And we’ll only be making it right

‘Cause we’ll never be wrong together

We can take it to the end of the line

Your love is like a shadow on me all of the time

I don’t know what to do and I’m always in the dark

We’re living in a powder keg and giving off sparks

Recall once again that the song’s composer and lyricist, Jim Steinman, planned the video, and chose to match those lyrics with these images of choirboys.

If the song is about the forbidden love between a teacher and an underage student, then we might have an explanation as to why the dove is clenched in the demonic child’s hands. Tyler has repressed not only her attraction to her students, but some memory of past sexual violence. This child who torments her, then, is both a symbol of her guilt as well as her continuing desire.

Well, perhaps we don’t want to go down that path. If so, we’re left with a relatively tamer reading. The dove at this point is fully restrained (in the child’s clutches). Whereas before Tyler’s desire could at least struggle to take flight, it is now fully at the mercy of the boys who surround her, and torment her (simply by attracting her). By this point, Tyler has finally lost touch with reality, having lost herself in her pent-up desires.

(On a side note: there are other doves behind the boy, which might suggest that Tyler isn’t alone in her desires. Could there be another teacher like her at the school, similarly tormented? And on another side note: Tyler’s vocal performance in this song is nothing short of magnificent!)

OK. We now find Tyler standing outside the school, confronted by the unearthly choir.

Next we see some of the teenage students (all partially undressed) running and jumping toward the front entrance of the school (3:47)—

—perhaps rushing to join the single student who kicked all this fantasy off. Tyler has come under siege. From that we cut to other students, their proper outfits disheveled, who (like Emo Kid) suddenly raise their heads to address the camera (3:49):

After this, Tyler is ringed by the incoming pack of boys. Their skimpy outfits fuse many of the elements we’ve thus far seen: swimsuits and gymnastics clothing, leather, tattered cloth (which also recalls the billowing curtains and the ruined table cloth). They dance orgiastically around their teacher, as though enacting some pagan ritual (not unlike the sacrificial dance in the The Rite of Spring).

From here, the action crosscuts between the wild dancing boys and shots of Tyler surrounded by choir boys, who form a ring around Tyler, their eyes aglow (3:47–4:30). The duality is perfectly clear: Tyler wants to tear the smocks right off those choirboys—and they know it! The way the younger children are juxtaposed with the older teens further suggests a pedophiliac reading, since the cutting directly associates the two pairs of youngsters (see in particular the cuts at 4:06, 4:15, 4:20, and 4:24).

The speed of the crosscutting increases until Tyler, finally overcome, collapses (4:24–4:30)—very Rite of Spring!

However, unlike that ballet’s sacrificial virgin, Tyler isn’t dead. An angel appears behind her and embraces her (4:32):

Several of the video’s elements—the dove, the angelic/demonic boy, the choirboys, the wild teens—merge here. For one thing, the angel’s embrace echoes the shot of Emo Kid clutching the dove. If we read the bird as Tyler’s desire (and I do), then it would seem that her desire has melded with the object of her desire, and totally enveloped her. In other words, rather than representing divine or external mercy, this encompassing angel represents the mercy of succumbing to one’s delusions. (See the ending of Brazil.)

The angel’s embrace prompts a quick cut to daytime—although note that our location (the school’s front steps) remains the same.

4. Coda (daytime) (4:41–5:33)

It is now the following day, and the fantasies of the previous night have been tucked away, once again repressed. Tyler appears alongside another school official, and dressed in proper the uniform of a teacher. She’s being introduced to a group of boys who are standing at attention. The emphasis is entirely on restraint, on decorum.

What’s happening here? I can imagine two scenarios. Either Tyler is new to the school, or these boys are new. The latter reading makes more sense: Tyler’s frustration seems a product of her already being a teacher at the school. What’s more, if the students are new, that would match the way the video began—with invasion from the outside. Each new school year brings new students, and the chance to start anew—and to lust after a new crop of boys, who are ignorant of Tyler’s deeper desires.

But something has changed. One boy isn’t standing in the line—he rushes up from behind, squirming through the line (4:54–6):

Now, unless I’m mistaken, this is the young boy with the wings who was holding the dove—Emo Kid. (If not, he certainly recalls him.) Seen in the light of day, the kid is animated and cheerful—innocent and cherubic:

But see what happens next. Tyler affectionately ruffles his hair (alarm bells should be ringing), then moves down the line, perfunctorily shaking hands with the other students. One of them doesn’t release her hand (5:06), prompting Tyler to look him in the face. A reverse shot reveals what she’s seeing (5:11):

Hello, fantasy!

Obviously this is the kid Tyler first imagined visiting her at night—he’s even singing the line that played when he first appeared: “Turn around, bright eyes.” (We also hear the sound of the car passing.) Her fantasy, which should be confined to nighttime and solace, is now happening in public in the daytime.

We have two possible readings here. First, there really is some secret Children of the Damned type conspiracy among the students, and they’re now collectively in on Tyler’s secret.

But given all the other elements of the video (in particular the passing car, the enveloping angel), I think the more likely reading is that Tyler is still imagining all of this. Having succumbed to her fantasies, she will now live lost in them at every hour of the day. The video suggests this reading a few shots later (5:19):

The boy is still singing (“Turn around”), but his own bright eyes are gone, and he’s facing the opposite direction. (This might be a simple continuity error, but it contributes to the feeling that Tyler’s own vision can no longer be trusted.) What’s more, his singing continues as the kids move past Tyler and up the stairs and into the school (5:27–5:33), suggesting that whatever she’s seen and heard, it’s all in her head. Furthermore, no one else has noticed anything amiss, has observed what Tyler just experienced. Even she herself doubts it—we see her blinking in a pair of reaction shots (5:14, 5:21).

Regardless of whether the encounter is real or imagined, in the end, we’re left with Tyler standing, shaken, alone on the stairs:

Obviously, after this long dark night of the soul, she will Never Be the Same. … And neither will we!

So there you have it: 4000+ words on a remarkable song and music video—to my mind, a true ’80s classic. And I didn’t even mention my secret reading: that the video is a work of X-Men fan-fiction set at Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters. Tyler is Emma Frost (the White Queen), and the winged student is Angel, and the bright-eyed student is Cyclops, who has somehow learned to control his optic blasts—perhaps under Ms. Frost’s strict tutelage? (Obviously this is plagiarism by anticipation, since Frost and Scott Summers wouldn’t begin their affair until well into the 2000s.)

All right, I’d better shut up, before I reveal too many of my own fantasies. Thank you for reading, and I look forward to your comments. (And special thanks to Elisa Gabbert for listening to me prattle on about all of this!)

P.S. I’d be remiss if I didn’t include a link to the literal version of the video, from which I took the image at the top of this post.

Tags: Bonnie Tyler, Faster Than the Speed of Night, Holloway Sanatorium, Jim Steinman, Meat Loaf, Russell Mulcahy, The World's End, Total Eclipse of the Heart, Village of the Damned, X-Men

I remember reading somewhere that there was some kind of erotic art in the late 19th century focusing specifically on ninjas—you’re probably right that their presence (as well as the way they’re presented) in the video is only because of ’80s excess, but I don’t know, I find something disturbingly sensual about ninjas.

I thought originally that the number of choirboys at 3:29 (by my count, sixteen) and the presence of the angelic boy and the Emo Kid had something to do with the eighteen disciplines of ninjutsu. I guess it sort of has to do with the boys and the various skills they’ve learned at boarding school, but that reading doesn’t exactly include any of the other boys in there—probably just over-analysis.

Anyway, great essay. Can’t stop listening to this song now.

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-6zcpv-NUltg/TasgA7vFTvI/AAAAAAAAAHM/MiMvEkGqQi8/s1600/teoth1.jpg

Huh. I believe I’ve only scratched the surface. The song/video require many more hours of study…

Sweet! Thanks!

Bright Eye Heart I Love

[…] their desks). As her imagination keeps running further and further afield, grow […]

Well… that was brilliant.

I had an 80s playlist playing on Youtube as I was sitting here doing some work, and this song was included. I watched the video and started thinking, “Is this portraying what I think it’s portraying?”. It captured my attention enough to google its meaning which led me here.

Thank you for verifying my suspicions with your over-analyzing to death.

[…] Total Eclipse of the Heart (the Bonnie Tyler music video) […]