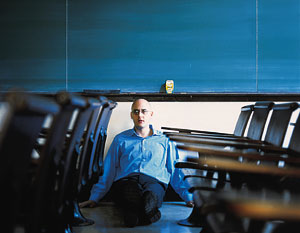

The following conversation between Colin Winnette (colinwinnette.com) and Ben Marcus (benmarcus.com) took place during the brutally mediocre winter of 2011. Both men carved a desk along with extra elbowroom into the walls of their unnecessary ice huts and began a steady email exchange. This was a final attempt to stay warmish. Listed below are the contents of that attempt. Special Thanks to Cassandra Troyan -The Eds.

Ben Marcus is the author of three books of fiction: Notable American Women, The Father Costume, and The Age of Wire and String. His new novel, The Flame Alphabet, will be published by Knopf in January of 2012. His stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in Harper’s, The Paris Review, The Believer, The New York Times, Salon, McSweeney’s, Time, Conjunctions, Nerve, Black Clock, Grand Street, Cabinet, Parkett, The Village Voice, Poetry, and BOMB. He is the editor of The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, and for several years he was the fiction editor of Fence. He has recently served as the guest fiction editor for Guernica Magazine. He is a 2009 recipient of a grant for Innovative Literature from the Creative Capital Foundation. In 2008 he received the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and he has also received a Whiting Writers Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in fiction, three Pushcart Prizes, and a fiction fellowship from the Howard Foundation of Brown University, where he taught for several years before joining the faculty at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.

*Portions of this interview first appeared in the Winter 2011 issue of the Tex Gallery Review

CW:Could you talk a little about your upcoming book, The Flame Alphabet? Its genesis and where things went from there?

BM: I’d been thinking for years about language as a toxic substance. Language itself making people sick. Speech and text, all of it poisonous. If you read a road sign you get nauseous. That was the original idea, but after Notable American Women I really didn’t want to write another heavily-conceptual, modular book. With that book, every new chapter felt like I was starting over. I wanted to write something continuous, a straight shot powered by one voice. I tried a lot of voices, forms, and approaches, and threw all of it away. But then I was doing some reading on underground Jewish cults and I found a pretty natural way to connect a language toxicity to a really personal narrative, even if that meant liberal falsifications and misreadings, and a story sort of bloomed fast out of that: a husband and wife who are sickened by the speech of their daughter. Literally. So sickened that they have to leave her. A situation so bad you’d have to abandon your child. This really frightened me, and I couldn’t even imagine it, which meant I had to chase it down. That was the opening premise, and once I had that I wrote the book in just over a year.

CW: When can we expect to see the new book?

BM: Knopf is publishing it in January 2012.

CW: How do you see it fitting in with your last two books, The Age of Wire and String and Notable American Women? Those books helped develop a reputation for you as being an “experimental” writer, but more recent work like The Moors, in a recent issue of Tin House Magazine, shows a capacity for more conventional narrative structures and imagery. Is there a particular dialogue you’re interested in developing between the works, or is each piece written for itself?

BM: I see some overlap because I seem to write about language a lot. Language as a physical substance with deviant powers. A powder, a drug, a wind, a medicine. I can’t really help it. But this book is a chronological narrative told by the main character. It’s got scenes and a story and sometimes it might even be suspenseful. It’s formally a lot simpler than my other books, and it felt entirely new to me when I wrote it. I’ve never written a single book-length narrative that has a clear plot. I loved being in such strange waters. It made me feel vulnerable and confused and completely unskilled, and this drove me crazy enough to bring everything I had to bear on the writing of it. In the end I want to write things that I don’t know how to write, because this seems to command the most energy and desire and attention from me. It makes me sort of sick with anxiety. When I’m uncomfortable and confused and curious I tend to try much harder to figure things out. Some of the basic narrative building blocks, which other writers seem to have mastered early in their careers, were just totally foreign and difficult to me. I’d dismissed them years ago for no good reason (other than fear and ineptitude). So I used techniques I’d never used before, even though people might consider them conventional.

This issue of experimentalism is hollow to me. I can’t figure out the actual content of the problem. I’ve never tried to write anything experimental, because I don’t even know what that would be. I’ve just written what most compels me at the time, what I’d most want to read myself. Does anyone self-identify as experimental? Anyone? When Notable came out, there were people who said it wasn’t experimental enough, and I’m sure I’ll get that again. But all I want to do is write something good, and not just return to familiar material or approaches. The Flame Alphabet, to me, seems far stranger and agonizing than The Age of Wire and String—it’s both weirder and sadder—but I realize that my own perspective on this hardly matters.

CW: Do you connect your experience as a writer, the motivational qualities of your anxiety and sickness with regard to your own language (or potential language, what you will write) to that of the husband and wife in The Flame Alphabet? Is this something you thought about with regard to the content of the book, or is this vocabulary of sickness and anxiety something that occurred to you later on?

BM: No, these are different things. I’m only talking about feeling vulnerable when I write so I can throw my whole self into it. Somehow it makes me feel more attentive.

CW: There are, or at least seem to be, strong autobiographical elements in your work, particularly in Notable American Women. But even The Age of Wire and String has a journalistic feel, if that’s the right word, a sense of someone privately mapping the world. Is this an impulse that comes out in the writing, or a conscious decision on your part to engage with a certain kind of narrative framework?

BM: I gravitate toward trying to make things seem true. I like the autobiographical tone, if not often the content. But those books aren’t remotely autobiographical, at least in the literal sense. Someone wrote an essay about The Age of Wire and String, declaring that it was essentially about a brother who had died, and the book was engineered to disguise and disclose the resulting pain the narrator felt. Except my brother is alive.

CW: Tell us a little about him. What does your brother do?

BM: He’s a public defender in Los Angeles, working on death penalty cases.

CW: You’ve championed the work of authors like John Haskell, work that blurs the distinction between fiction/nonfiction, but your work, to me, seems less interested in any kind of narrative truth-telling. Rather, you seem to extract what might be the emotional content of an autobiography, the confessional intimacy, and infuse it into a bizarre world of cloth, birds, masks, silence, etc., in a way that is thrilling, terrifying and eerily familiar. What’s your interest in these distinctions? How do you negotiate fiction versus nonfiction, or are these even useful thoughts to have?

BM: I think you’re right: the emotional content of autobiography. That’s it exactly. But really, in the simplest terms, I want to create feeling. I want to make readers feel things. Wouldn’t a lot of writers say the same thing? And these kinds of images and stories are the best way I know how, so far. But I am fascinated by nonfiction. Some of my very favorite writers are essayists. D’Agata being a huge one. I love writing essays, and I’d love to write a novel that is structured like an essay, but I haven’t figured out how to do it yet. I have some fictional essays in the collection of stories that’s coming out after The Flame Alphabet. From my earliest pieces, I was drawn to nonfictional rhetoric. The language of the encyclopedia, semantical authority, prose that seemed informationally inviolable. But I guess I burned out on that after a while. I think the interest is still in me, but until I can find a way to replenish it and do something different, I’m going to wait.

CW: You’ve said your work is often about language. The Age of Wire and String, seems particularly interested in the potential for revitalization, or its malleability at least. When you’re setting out to write a book, are you interested in setting up a problem, like, say, the limits of language, and either working through it, or simply exhibiting it? Does that kind of thing even occur to you?

BM: I don’t really have to set up a problem, because there are so many problems already set up, already waiting. I tend to find the problem half way down the first page, and if I like it, which means that it scares the shit out of me, I might keep writing. I try to figure out the best way to trigger adrenaline, and then I look to escalate everything as quickly and believably as I can. Tom McCarthy described Remainder as a set of escalations on a theme, and I really like that idea.

CW: What’s the scariest thing you’ve ever written? A line, a story, a book, a word. If there’s too much, maybe just make a short list of the first things that occur to you?

BM: Can’t think of anything anymore, because it all gets neutralized pretty fast and it stops scaring me. I’m always chasing it. Maybe it’s what I’ll write next.

CW: What was the most recent thing you read that stuck with you? Excited, terrified, disgusted, depressed, etc. What do you find tends to most often elicit a response?

BM: New translation, by Mark Ford, of Raymond Roussel’s Impressions of Africa. About a Mountain, by John D’Agata. Of course The Ask, by Sam Lipsyte. Best novel of the last few years. I’m really glad I can’t answer your last question.

CW: Finally, a question about MFAs. I imagine it’s difficult to say, but what’s your advice to writers considering, or pursuing, a graduate degree, a second graduate degree? Could you talk a little bit about your experience at Columbia?

BM: I think writers should do exactly what they need to do to get their work done, whether that means going to school, going abroad, taking a job on a tanker, licking men’s backs, or hiding in an attic. Lots of writers thrive in the MFA atmosphere: tons of critical feedback, heavy reading, broad exposure to different kinds of writing. But other writers don’t really get much out of that kind of community. To me it’s about knowing what you want, understanding what might help you develop. Some programs revolve around the workshop, with some low-impact electives in the background. Other programs have a rigorous curriculum on top of the workshop with lots of craft-based courses. Again, it depends on the writer. What I love most about Columbia are the students. Year after year there are intense, curious, hard-working students, and they are all different. I feel lucky to be around people who care so much about writing, who want so much to improve, and who test out their instincts so fearlessly. This is the best part of the job: a community of people with the same passion.

BM: I think writers should do exactly what they need to do to get their work done, whether that means going to school, going abroad, taking a job on a tanker, licking men’s backs, or hiding in an attic. Lots of writers thrive in the MFA atmosphere: tons of critical feedback, heavy reading, broad exposure to different kinds of writing. But other writers don’t really get much out of that kind of community. To me it’s about knowing what you want, understanding what might help you develop. Some programs revolve around the workshop, with some low-impact electives in the background. Other programs have a rigorous curriculum on top of the workshop with lots of craft-based courses. Again, it depends on the writer. What I love most about Columbia are the students. Year after year there are intense, curious, hard-working students, and they are all different. I feel lucky to be around people who care so much about writing, who want so much to improve, and who test out their instincts so fearlessly. This is the best part of the job: a community of people with the same passion.

CW: Annnnnd, had to ask, how was it working with James Franco? Any workshop stories worth telling?

BM: James was a great student. Serious and hard-working, hugely committed to his writing. He’s well-read, curious, and incredibly productive, and it’s been great to watch his work develop. The novel he’s working on now is pretty fascinating. Can’t say any more than that.

CW: Thanks for talking with me, Ben. Anything more you want to say before we go? Anything you wish I’d asked?

BM: …

***

Ben Marcus will give a reading from his forthcoming novel The Flame Alphabet at Tex Gallery in Denton, TX on Saturday, April 2nd, 2011 at 9pm.

(texgallery.org, or check facebook for more info, and visit Colin Winnette here)

Tags: ben marcus, The Flame Alphabet

“His new novel, The Flame Alphabet, will be published by Knopf in January of 2012.” Did the writer mean 2011?

Nope, Mr. Marcus says 2012. It was originally slated for release this fall, but they’ve apparently changed the date.

Thanks for clarifying. That’s a long time to wait.

I know! I was surprised/disappointed to hear of the change myself. But he’s touring around this year, reading from the book. So there’s always the opportunity to track him down and hear more that way.

Great interview. Thanks for sharing it.

Good stuff, Colin!

[…] interesting than my muffins: a former classmate of mine from Sarah Lawrence recently interviewed Ben Marcus for HTMLGIANT. Ben Marcus! That is […]

Thanks, Cass. And thanks for your help with this!

Love this graf:

This issue of experimentalism is hollow to me. I can’t figure out the actual content of the problem. I’ve never tried to write anything experimental, because I don’t even know what that would be. I’ve just written what most compels me at the time, what I’d most want to read myself. Does anyone self-identify as experimental? Anyone? When Notable came out, there were people who said it wasn’t experimental enough, and I’m sure I’ll get that again. But all I want to do is write something good, and not just return to familiar material or approaches. The Flame Alphabet, to me, seems far stranger and agonizing than The Age of Wire and String—it’s both weirder and sadder—but I realize that my own perspective on this hardly matters.

Love this graf:

This issue of experimentalism is hollow to me. I can’t figure out the actual content of the problem. I’ve never tried to write anything experimental, because I don’t even know what that would be. I’ve just written what most compels me at the time, what I’d most want to read myself. Does anyone self-identify as experimental? Anyone? When Notable came out, there were people who said it wasn’t experimental enough, and I’m sure I’ll get that again. But all I want to do is write something good, and not just return to familiar material or approaches. The Flame Alphabet, to me, seems far stranger and agonizing than The Age of Wire and String—it’s both weirder and sadder—but I realize that my own perspective on this hardly matters.

I enjoyed this. Thanks, Ben, for the clarity.

i take ‘experimental writing’ to refer to work that’s prototypically avant garde, foward-thinking, though ultimately ends up in a cultural cul de sac upon publication, reception; in essence: a unsuccessful experiment. that’s how it earns the tag in the first place. using the word ‘eclectic’ makes more sense to me to refer to cases in which the sheer strength of an oddball work outlasts the unreceptive environment it was thrown into, like, for example: Tender Buttons, Finnegans Wake, Moby Dick, et al.

oh, another: Tristram Shandy

Marcus’s statements about experimental writing strike me as very simplistic. At worst it romanticizes his own process. No harm there, but it is silly. At the best it is perhaps a put on for the interview. The fact the trope is repeated in a couple days here by Amy McDaniel’s suggests that at least this idea that there some kind of “problem” with the term experimental (requiring to be quarantined in quotes) has infected HTML Giant. Does anyone identify as an experimental writer? Yes. A lot of writers have and continue to identify their work as experimental. Personally I am essentially a conventional writer. I tend to work within defined traditions and forms. However I know the work of contemporary novelists such as Doug Nufer, Eckhard Gerdes, Stacey Levine, and Lilly Hoang — they have written work that is experimental wearing the quotes of “experimental writer.” In the past a writer such as Gertrude Stein certainly worked in the stance of experimental writer–and saw her work being more in line with scientific inquiry than what Marcus is describing here as a mostly an art based on the impulse “to do something good.” The tradition of Surrealism and the OULIPO is enough to clearly show that there is a process associated with literary experimentation. Reading the Age of Wire and String for me was an exercise in understanding how procedural based concepts could be used to generate text. It is fine that Marcus wants to obscure the composition of his books. It is a common practice I think to remain mum on how you wrote your book. One of the potential beautiful features of an experimental work is the appearance of a marvelously strange object that makes you wonder how it came to exist. But I still find the schematic for the composition of If On a Winter’s NIght a Traveler very interesting, and in fact makes it’s composition seem even more marvelous.

I think applying Avant Garde to experimental confuses the issue, but understand the source of confusion since many modern works that were experimental were also Avant Garde. I think the Avant Garde has run its course — there is in center to overthrow and no margin to bring in — but experimental writing and conventional writing continue to be useful modes.

[…] Ben Marcus is not serious about not being an experimental writer. Come on, HTML Giant… keep up with the […]

I’m sorry if I offended anyone here. I wasn’t at all trying to obscure the composition of my books, and perhaps I just have a weak understanding of this very odd word–experimental–when it comes to writing. I’ve never pretended to be a terrific guide to what I’ve written. Maybe I should have played as dumb as I sometimes am about this kind of terminology. I suppose that I’ve seen this term used in polarizing, dismissive ways so many times now that I’ve stopped enjoying it. It’s lost its charge for me and I honestly don’t even know what it’s meant to refer to anymore. Markson, one of the most intense and original novelists of the last one hundred years, didn’t see himself as experimental at all. Nor does Diane Williams. These are two writers I’d kill for, and I also can’t hold a candle to them. These are writers some identify as experimental, while others just see them as killer artists. I don’t write with a separate, conscious awareness of where my work fits into the aesthetic continuum. I tend to be pretty instinctive and emotional. And for whatever reason I’ve never been able to genuinely declare myself to be experimental. I think that, in retrospect I should not have said that nobody self-identifies as experimental, when clearly there are writers who do. That was boneheaded.

Matt,

I’m not really seeing what the issue is you have with Marcus’s responses here, or what makes you think that he’s being disingenuous and/or “obscur[ing] the composition of his books.” To me it felt an honest, candid, even humble response, fairly open about being guided by emotion primarily, plus the idea of language toxicity, and how that idea intersected with reading about underground Jewish cults, at least for the new book. If conventional narrative structures have eluded one and one tries them on later in one’s career, then do they become “experimental”? I get the sense that Marcus was just challenging the use of this word as shorthand, that we too quickly accede to an understanding of what this word means. This to me seems more productive than trying to uphold a dichotomy between “experimental” and “conventional.” .

Mr. Marcus is obscuring the composition of the books, but my understanding from his response (here) is that the composition of his books are actually obscure to himself.

My issue with Marcus’ response was two-fold. 1) Are there writers who identify themselves as experimental. That’s been addressed. 2) Does the term experimental mean anything?

It does mean something, and it means something in terms of composition that is very specific.

As a reader and writer, I am very self-conscious. Certain terms seem to mean very specific things, even though their definitions are often reductive. For example, many writers pretend to be completely lost when discussing the meaning of some basic terms composition, such as “story” or “plot” or even “sentence.” I think a prolonged analysis of these terms can be very productive, such as Ron Sililiman’s look at the “sentence” in The New Sentence. However, I have sat through a dozen workshops or panels in which prose writers have been unwilling to clearly articulate what a sentence is much less a story. Far from teasing out nuance or being productive, these writers who are unwilling to define first terms for a room of writing students come across as incompetent and ineffectual at talking about writing. While it has been very productive to examine first principles for composition, at a certain point, a lay language must be established (and in fact has been established, I would argue) for composition. There are working definitions and first principles, and yes, the terms story, plot, sentence are problems, but every experienced writer knows what a story, plot, or sentence is. Definitions are reductive. Given. Define. Move on. The term “experimental” is I think a term as basic as story, plot, or sentence. Its meaning exists in opposition to the conventional. It speaks to a process that has been used for a very long time to create experimental writing. It is not a new term. Can the term be cracked open? Sure. Given Marcus’ response, I guess he really does not engage in the kind of deliberate process that is that is a “separate, conscious awareness of where [his] work fits into the aesthetic continuum.” Writers such as Donald Barthelme (Not Knowing), Gertrude Stein (How to Write), the OULIPO (published their methods in the OULIPO pamphlets), etc. have engaged in experimental writing.

The term experimental is useful and has a long history, despite being used in a polarizing, dismissive, or charged/uncharged way. Marcus is familiar with this history, and I believe most readers and the bloggers who post here are familiar with the meaning and the history. So, I guess that was my issue.

Marcus is definitely well-versed in the history; I agree with you there. His classic article in Harper’s on the topic argues strenuously that the distinction between “realist” and “experimentalist” is largely a distorting one. To quote from the article, “If literary titles were about artistic merit and not the rules of convention, about achievement and not safety, the term ‘realism’ would be an honorary one, conferred only on writing that actually builds unsentimentalized reality on the page, matches the complexity of life with an equally rich arrangement in language…[i]n such a scheme, Gary Lutz, George Saunders, and Aimee Bender would be considered realists right alongside William Trevor, Alistair MacLeod, and Alice Munro.” This is slightly different from the dichotomy between “conventional” and “experimental,” but one might make a parallel argument.

I’m not suggesting that those terms–plot, character, sentence–aren’t useful, and that we ought to mystify everything. But what I took Marcus’s point in the interview to be was that the term “experimental” can be misleading, just as can the term “realism.” It can lump together, for one, writers doing diverse things, thus obscuring the nuances of their work. To take just one example, you mentioned surrealists and OULIPO in a single breath, when one impetus behind OULIPO’s formation was the rejection of surrealist techniques. Hence, too, those writers who were deemed “minimalist” in the 80s who squirmed under the designation, felt it put them in a pigeonhole, and not a particularly flattering hole. And I think it’s notable that many writers reject the designation of “experimental.” From an interview with Josh Cohen: I hate the word “experimental”… It’s like what they say on television: “If you liked ‘Experimental,’ you might like…”

“Eclectic”, meaning ‘variegated; mixture of styles’, doesn’t connote, to me anyway, ‘experimental’ or even ‘unconventional’. Do you mean eccentric?

Tim, I think we are getting close to agreeing in essence. We are using the term “experimental” in pretty much the same sense. The term hardly seems hollow, and it seems useful. I understand the objection to labels and shoes, but if the shoe fits.

We’re getting there, Matt. I think we agree that if the terms are useful then they merit use and otherwise not–the shoe has to fit and it has to yield some treading mileage. I don’t think we’re going to agree on all of the particulars, but thanks for the thought-provocation, especially re: how “experimental” fits with other literary terms.

[…] Winnette, “I Can’t Really Help It: A Conversation With Ben Marcus,” HTML Giant January […]

[…] from a long, really nice interview with the extraordinary Ben Marcus (with Colin Winnette) This issue of experimentalism is hollow to me. I can’t figure out the actual content of the […]

whoops, yeah. though eclectically eccentric, eccentrically eclectic… kinda works…?

[…] I Can’t Really Help It: A Conversation with Ben Marcus Colin Winnette / Ben Marcus htmlgiant.com A link from Elizabeth Allen with an interview wherein an author discusses his novel in which language becomes toxic. I will note a disagreement with Marcus’ use of the word “cults” in one particular sentence. I’d been thinking for years about language as a toxic substance. Language itself making people sick. Speech and text, all of it poisonous . . . . a story sort of bloomed fast out of that: a husband and wife who are sickened by the speech of their daughter. Literally. So sickened that they have to leave her. A situation so bad you’d have to abandon your child. […]

Want to use death as an adivsor?…

Now you can: there is a free app for this. No ads, no upselling, no malware, no catch. If it helps you, great….

[…] though I can’t remember any of it now. It didn’t work for me. His forthcoming book, The Flame Alphabet, sounds amazing – the central premise is the toxicity of language, how irresistable is that. He […]

Bit late arriving here, but re Marcus’s suggestion that Markson ‘didn’t see himself as experimental at all’: when I published Markson’s This Is Not a Novel in the UK last year, one of the quotes available for the cover was David Foster Wallace’s line on Wittgenstein’s Mistress being ‘pretty much the high point of experimental fiction in this country’. I told Markson that word would put readers off. He replied, in a letter: ‘As an obvious experimental writer, and with this being an obviously experimental book, I think you’re wrong to shy away from the word.’

Good to know, Charles, and thank you. I had a long conversation with Markson about this question and some other things, and he seemed shy about the term then. I miss him and his work. A really killer essay needs to be written about just how groundbreaking he was. No one writes like him at all.

[…] features a single first-person narrator, who chronicles events in a more or less linear fashion. In a recent interview on HTMLGiant, you remark that the novel was exciting to write for just this reason. After playing […]

[…] Things Considered interview with the author HTMLGIANT interview with the author Philadelphia Inquirer profile of the author Philebrity interview with the author Salon interview […]

[…] and interviewers are billing Ben Marcus’ new novel The Flame Alphabet (Knopf) as a departure for the author, whose […]

[…] a sucker for the off-beat and/ or experimental I head on over to Marcus’s site, which links to an interesting interview with him at HTMLGiant. And, yet again, a new book is added to the top of my reading list as Marcus […]

We love you anyway, Ben, boneheaded or not. Though the term experimental sends delicious shivers down me, I know quite a few people seem to associate experimental with something negative. Being hyper-aware of the literary continuum, I find it startling to read about you not having an awareness of your place in it. Always good to get a chance to stretch into a different perspective. Thanks.

Was this before or after you wrote a blurb for James Franco?

[…] experimental Marcus often preceded it with “so-called.” And when an interviewer at HTMLGIANT brought the word up a few years back, Marcus reacted sharply, “This issue… is hollow to me. I’ve never tried to […]