Film

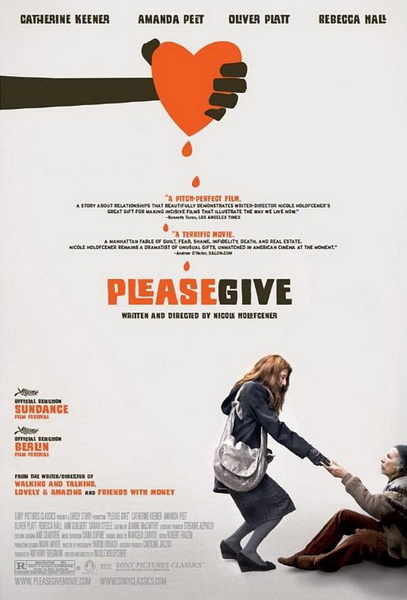

GIANT Guest-post: Kati Nolfi on “Please Give”, Catherine Keener, and the Holofcener oeuvre

“Oh my God!” and “This is horrible!” clucked and gasped the audience of Please Give. They were responding to the film’s many cynical and self involved remarks. It wasn’t as antisocial as a Todd Solondz film, but people are unused to women representing and speaking their ugly truth on film. Nicole Holofcener’s movies show angry, bitchy, unhappy characters—usually women—in unflattering lights, such as laughingly wondering if you can fuck in a wheelchair, or hoping for the death of an elderly person. But unlike other directors who show the worst of human relationships—Neil Labute, for example—Holofcener has compassion for her characters. She and her actors create multidimensional portraits of women, mostly white and upper class. When she attempted to deal with race in Lovely & Amazing, it was awkward. For all the flaws and missteps in Holofcener’s movies, they address class when most films do not. There is honesty in these movies about how class separates people, how we hang out with our own kind, though sometimes I wonder how critical she is being. And her women, as horrible as they may be, are respected as whole fallible humans.

“Oh my God!” and “This is horrible!” clucked and gasped the audience of Please Give. They were responding to the film’s many cynical and self involved remarks. It wasn’t as antisocial as a Todd Solondz film, but people are unused to women representing and speaking their ugly truth on film. Nicole Holofcener’s movies show angry, bitchy, unhappy characters—usually women—in unflattering lights, such as laughingly wondering if you can fuck in a wheelchair, or hoping for the death of an elderly person. But unlike other directors who show the worst of human relationships—Neil Labute, for example—Holofcener has compassion for her characters. She and her actors create multidimensional portraits of women, mostly white and upper class. When she attempted to deal with race in Lovely & Amazing, it was awkward. For all the flaws and missteps in Holofcener’s movies, they address class when most films do not. There is honesty in these movies about how class separates people, how we hang out with our own kind, though sometimes I wonder how critical she is being. And her women, as horrible as they may be, are respected as whole fallible humans.

Holofcener seems to process her own experiences through film, with Catherine Keener as her proxy. Like Pedro Almodovar, her depiction of female reality resembles actual life experiences (see the mother-daughter shopping scene in Please Give) and she works well with female muses that depict a range of womanhood. Her characters are losers who have no reason to be losers. They have money, partners, kids, they’re supposed to be sorted out; and yet they’re petty, selfish, and unhappy. This can be a frustration for some viewers: How can these women be such strong characters, yet be so miserable?

In almost all of Catherine Keener’s films, she is a Difficult Woman and sometimes a cartoon of the Brunette Bitch, Woman as Monster, such as in Being John Malkovich. She has a power that radiates from her carriage, eyeroll, and cool intelligence, like she’s meant for something greater and slumming. Please Give is the culmination of her work with Holofcener, their fourth movie together, and probably the last. Holofcener’s films—Walking and Talking, Lovely & Amazing, Friends with Money, and Please Give—add up to a lot of uncomfortable affluence, taste signifying meaning, and troubled relationships. Holofcener inverts the meaning of Sex and the City (episodes of which she has directed) with her films. In the movies, redesigning bodies and homes results in catastrophe. There is little pleasure in sisterhood here, whereas in SaTC, female friendships are the only possible respite from commercialism, though they are often the site of consumption as well. Friends with Money and Walking and Talking have the most positive friendships—romantic relationships are consistently fraught—though their foundations are unstable.

Since female friendship is a constant theme, Keener and Holofcener’s relationship also is central to the making of movies. Their relationship is more equal (Holofcener calls it “collaborative”) than the typical artist-muse relationship, in which the muse-woman nurtures male genius and is the recipient of male power, women inspire the aesthetics and men dictate the terms. Since there are few women directors to begin with, the successful ones are often overly analyzed: what’s their secret? Are they making action movies that could be directed by men without anyone noticing (Kathryn Bigelow) or do they occupy the sweet spot of girly escapism (Nancy Meyers). Holofcener often admits how personal her movies are—she too “gives out $20 bills”—unlike most directors who insist on the protective scrim of fiction.

While the humanity of her principal characters is lauded, the othering of characters who are people of color, poor, or differently-abled is not interrogated, or even addressed. This is troubling. To some degree, the othering itself is probably intentional, to show how insular the worlds of the wealthy protagonists are. When a character in Friends with Money becomes a housekeeper, her friends are so horrified and confused that one asks, “Is that, like, hip now? Cleaning houses? Like a Zen, so-unhip-it’s-cool.” Keener’s Kate in Please Give gives away money freely (although the occasional $20 to someone on the street might seem like a lot, how much are those beautiful clothes she wears?) because she feels bad for having a job that takes advantage of the dead and their relatives. She feels guilty and has those eyes that are always pre-cry, but has trouble connecting and gets visibly sad at the children and elderly for whom she wants to volunteer. She can’t deal with the guilt from benefiting from others’ suffering, yet she can’t remove herself from the machine that causes the suffering. Most of us can’t, but she seems stuck on her rich NYC life, buying those $200+ jeans to make her daughter happy. Maybe she could move beyond guilt if she gave up some privilege or saw homeless people as human, just without the unearned privileges she has. Her and her husband’s work and living plans necessitate celebrating when old people die so they can move in or break through, and mark up that vintage furniture for resale.

While Holofcener’s women can be cruel, they often show more empathy than the men. Holofcener has mentioned that she has trouble “enjoying my life when others aren’t enjoying theirs.” Friends with Money and Please Give have a similar exchange between partners. The men accuse their wives of being transformed, of being too involved with others. Respectively,

(1)

“You care too much what people think.”

“Just because you can remove yourself to feel superior doesn’t mean I can”

(2)

“Your guilt is warping you.”

“Why isn’t it warping you?”

Although many reviewers insist that Please Give is about guilt and charity, I think it’s about the anxiety of aging. Similar to L&A, the principals are a wide range of ages. Catherine Keener bitterly calls Amanda Peet’s Mary “young and pretty,” but Mary is later called “old” by the girlfriend of her ex-boyfriend. Characters are too young, too old, or too dead, wanting to transfer out of their situation, to be in someone else’s. Holofcener’s movies are thought provoking, but upsetting and uncomfortable. They end with giving-up and acquiescing. Holofcener’s characters seem to be the sort who say, “It is what it is.”

Tags: Catherine Keener, Kati Nolfi, Nicolle Holofcener, Please Give

So best. (I think it’s about NYC and desensitization, but anxiety of aging works too.)

Also,

> the othering of characters

is a mirror-to-life issue? an anxiety-of-Woody-Allen’s-influence issue? a directors-are-rich-people-too issue?

i enjoyed reading this. catherine keener has been a favorite performer of mine ever since i first watched walking and talking on vhs. although always type-casted, she is consistently fantastic in every roll. holofcener, on the other hand, is a hit-or-miss filmmaker; lovely and amazing and walking and talking were decent films, but i thought friends with money and please give were just awful. bad writing, terrible pacing, underdeveloped characters (which is odd, because as you pointed out, her characters are overly developed to the point of neurosis, and that’s why i love them), and crappy filmmaking. the surprising (?) thing is that keener doesn’t need a female director like holofcener; she has been put to brilliant use by spike jonze and charlie kaufman, two male directors who “collaborate” much more effectively with keener than holofcener, i think. or maybe they just make better films

Thanks, this is very interesting. I felt like Please Give suffered (don’t know if I wrote this in the review) from too much story, too many characters. Maybe half of the characters would have made a better movie. There’s something about Keener I think that elides (or not) the ickier possibilites in a movie like BJM (and maybe Living in Oblivion, don’t remember) where she is asked to play a monster. As flawed as Holofcener’s films tend to be, I guess I overlook them because they present a compelling tableau of a certain type of lady. What are the liberating possibilities in the bitch, if there are any, or can it only be sexist stereotyping and do the filmmakers’ genders have everything/anything to do with it? Still thinking.

So best. (I think it’s about NYC and desensitization, but anxiety of aging works too.)

Also,

> the othering of characters

is a mirror-to-life issue? an anxiety-of-Woody-Allen’s-influence issue? a directors-are-rich-people-too issue?

i enjoyed reading this. catherine keener has been a favorite performer of mine ever since i first watched walking and talking on vhs. although always type-casted, she is consistently fantastic in every roll. holofcener, on the other hand, is a hit-or-miss filmmaker; lovely and amazing and walking and talking were decent films, but i thought friends with money and please give were just awful. bad writing, terrible pacing, underdeveloped characters (which is odd, because as you pointed out, her characters are overly developed to the point of neurosis, and that’s why i love them), and crappy filmmaking. the surprising (?) thing is that keener doesn’t need a female director like holofcener; she has been put to brilliant use by spike jonze and charlie kaufman, two male directors who “collaborate” much more effectively with keener than holofcener, i think. or maybe they just make better films

[…] HTMLGIANT / GIANT Guest-post: Kati Nolfi on “Please Give … […]

Thanks, this is very interesting. I felt like Please Give suffered (don’t know if I wrote this in the review) from too much story, too many characters. Maybe half of the characters would have made a better movie. There’s something about Keener I think that elides (or not) the ickier possibilites in a movie like BJM (and maybe Living in Oblivion, don’t remember) where she is asked to play a monster. As flawed as Holofcener’s films tend to be, I guess I overlook them because they present a compelling tableau of a certain type of lady. What are the liberating possibilities in the bitch, if there are any, or can it only be sexist stereotyping and do the filmmakers’ genders have everything/anything to do with it? Still thinking.

Interesting read.

Interesting read.