Film

Why Can’t Monsters Get Along With Other Monsters: Thoughts on Pacific Rim, Lovecraft, and the Endless Abyss

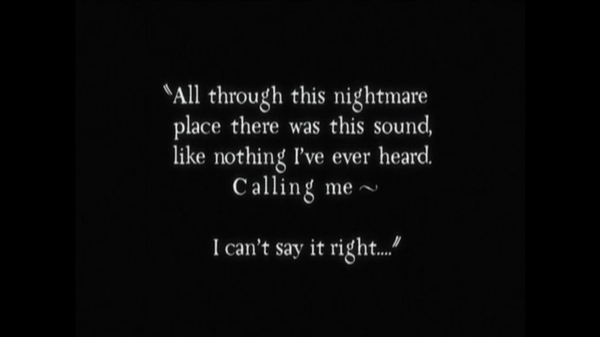

– H.P. Lovecraft

Essentially every culture has a mythological history which includes primal, undifferentiated formlessness: the abyss, as much topless as it is bottomless. Figuratively speaking, this abyss is neither aquatic nor interplanetary. Rather, it’s a little of both. The howling Tao, the primal ocean upon which Vishnu slumbered, amorphous being, chaos preceding time, primordial stew.

Today, in cockpits and bathyspheres, astronauts and their aquatic counterparts contort into metal cabins, surrounded by death, to peer from thick windows into empty, hostile landscapes. Cloaked in metal, they transport light where there has never been any — to what James Cameron, after his much-ballyhooed 2012 submersible dive to the Challenger Deep, called a “barren, desolate lunar plain,” or (more viscerally) which William Beebe, passenger in the world’s first bathysphere, described as “the black pit-mouth of hell itself.” From this hell-mouth emerge our literature’s greatest monsters, those embodying primeval dread itself: the Kraken of maritime myth, Godzilla, Cthulu, and now, the Kaiju aliens, which shimmy through an interdimensional breach at the bottom of the ocean and sow chaos on the coasts of the world in Guillermo Del Toro’s magnificent new film, Pacific Rim.

I’m still smarting from my last foray into genre categorization, so I’ll keep this brief, but if there exists a matrix for science fiction v. horror, it would be a graph plotted on two axes: time on the one hand, distance on the other.

The Platonic form of science fiction lives on the far right corner of this graph, distant in both time and space, in a galaxy, far, far away, or a time beyond our own (see Isaac Asimov’s Foundation novels, or the future-histories of Olaf Stapledon). Of course, ample science fiction is distant only in time, and some even transpires in the past — Star Wars, for instance. And yet more is so psychedelically transcendent that it takes place nowhere, nowhen. Still, the sweeping tendency with sci-fi is the desire to get the hell away from familiar burdens: it’s designed to relieve the anxiety of present existence, or to sublimate it into art through de-familiarization. More can (and has been) said on this subject, but I digress.

On the other end of the graph, in the opposite corner — ancient and subterranean — lurks horror. There are countless nuances and exceptions, but I find this to be a useful rule of thumb. Consider that everything frightening in the canon of H.P. Lovecraft is both terribly ancient and terribly below ground: tombs, caves, subterranean shoggoths, sunken cities. In horror, the shock of difference doesn’t come when we launch ourselves out of the solar system and into the arms of waiting little green men; it comes when incomprehensibly ancient monstrosities come bellowing out of the black maw of our very own world. It is the compounded hideousness of our planet, pressed like carbon by the forces of nature into scintillating gems of unspeakable gnarlitude.

The safe zone for humanity is a gauzy layer of atmosphere between brute rock and faceless void; our fears tend to manifest from above and below. So one could say that the difference between science fiction and horror is simply a question of direction. While they both speak to a fear of the unknown, science fiction handles the unknown hovering just out of reach, and horror the unknown lurking beneath — or, perhaps, even, within. Pacific Rim is both. It’s everything. Despite all its outward appearance as a romper-stomper robot punching movie, Pacific Rim lingers in the mind like a question for days; It has a sly, beating heart which seems to soften even the toughest of cookies. Even William Gibson has been tweeting in great zealous jags about the film, calling it “a baroque that doesn’t curdle, that never fetishizes itself.” Its metaphors have a kind of squishy durability. I’m pretty sure “neural handshake” will become vernacular for tiers of intimacy in certain relationships.

It has its predecessors, of course: Godzilla and his kin, King Kong, Transformers, and the big bad grandaddy of ancient monsters, the old one himself, Cthulu, an octopus-headed cosmic entity dreaming among sunken ruins beneath the sea. These monsters tend to be our fault, summoned by atomic carelessness, designated to punish our foolish sense of self-worth, or seduced by our increasingly toxic atmosphere. Why do movie monsters continue to bellow from insectile mouths? And why do their mouths always contain more mouths, nesting like matryoshka dolls, each more chitinous than the last? And at the very last, why do they always have a phosphorescent tongue like the genitalia of a slug, primed to make delicate contact with a single shuddering human, in a moment of perverse grace within the chaos of a shattered port city?

Pacific Rim gets at the formalism of monstrosity. Like the “Prawns” of Neill Blomkamp’s District 9, the Kaiju come to Earth as aliens–albeit through unconventional means. The film’s action begins five years after the initial point of contact, however, and in the intervening years the aliens have become pop-culture icons, have fostered a black market of Kaiju goods, have engendered fanboy sympathizers with Japanophilic tattoos. The Kaiju are (literally) the biggest thing ever, and, like serial killers fielding love letters in jail, they’ve developed into fetish objects. And although they haven’t become banal, they have shifted categories. They’re not aliens anymore. Like the Prawns, their novelty has worn off. We know them well, and we’ve discovered they’re assholes through and through. They’ve become monsters. Another way of saying this: monsters are just aliens on Earth.

Aliens are by definition the pure unfamiliar; monsters, on the other hand, are the ur-familiar, horror primeval. In Pacific Rim, the world embraces the Kaiju with equal measures of rhapsodic pleasure and terror. The turn-of-the century horror writer A. Merritt called this phenomenon the “unhuman mingling of opposites,” a combination of “ecstasy unsupportable and horror unimaginable.” Or Rilke, more famously: “beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror which we are still just able to endure.” Like the call of the sirens, or the call of Cthulu, the impossibility of turning away from something frightful once discovered, the compelling quality of true awfulness. Fantastic. No wonder Charlie Day’s Dr. Newton Geiszler wants to mind-meld in the drift with a Kaiju; it’s the ultimate trip.

I can’t help but wonder at the Kaiju world. Do they live like dinosaurs, screeching and tearing each other apart? As always in these kinds of films, we only get a glimpse of the enemy’s home planet in the instant right before it is destroyed in one blooming, orgasmic shudder of blue light. It looked like a shitty place to live. Maybe they didn’t grok that we were even sentient; as we might raze an anthill, they clobber cities. Scientists who work in SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) often ponderously raise this point–there’s always the possibility of being far too removed to communicate with any alien species we might eventually come into contact with. “We may well be able to communicate…because we share a common universe; because the laws of physics and chemistry and the regularities of astronomy are shared by them and by us,” wrote Carl Sagan in 1978, “but they may always be, in the deepest sense, different.” We make no attempt to chit-chat with amoeba. It’s not even particularly an issue of technological advancement or intelligence. A difference in size may be enough.

And, oh, the size! Has anything so monumental ever graced the silver screen? The scale of Pacific Rim‘s beasts has its own transcendence: something as massive and indifferent as a Kaiju negates all human concern. Like monuments and cathedrals, like the universe itself, it humbles, implies the existence of greater and more obscure realms of existence. Watching twin Jaeger pilots drop down an elevator chute and into their throne, perched on the shoulders of a metal giant primed to go punch monsters at sea, I thought: this is the modern Colossus of Rhodes. A trophy built from the spoils of war. A brazen giant, legs astride land and sea. Above all, it’s the ultimate human folly, an attempt to get on the level with the gods, to Cancel The Apocalypse. To fight monsters, we must create monsters, they say; they don’t tell us if we have to become them too.

Shakespeare, from Julius Caesar:

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonorable graves

In the classical world, as in the Cthulu mythos, man’s petty concerns are irrelevant in the face of the inscrutable and vast horrors of the cosmos. Trying to perceive reality breaks the mind. We can only play, like infants, between the toes of the gods and monsters astride the world. Or on their shoulders. Occasionally a Jaeger pilot clambers out of the lid of his machine’s brain to face the demon itself. Like David and Goliath, except to die in the claws of such a monster is a rapture of pure dread.

***

Claire L. Evans is a writer and artist working in Los Angeles, California. She is one-half of the conceptual pop group YACHT, the author of High Frontiers, and many articles about space. She tweets @TheUniverse.

Tags: guillermo del toro, h. p. lovecraft, horror, science fiction, silver golems

DAMN. Raising the game. So happy to read this, and see Claire over here.

awesome

[…] Why Can’t Monsters Get Along With Other Monsters: Thoughts on Pacific Rim, Lovecraft, and the …, HTMLGiant […]

oooo, I liked this. I’ve been thinking of Pacific Rim within a different dramatic plane, and you pushed my mind beyond the immediate. But I feel the article stopped just when it was getting started. :(((((((

This movie truly is fantastic. Instant classic?

“…in Guillermo Del Toro’s magnificent new film, Pacific Rim.”

IT IS HARD TO READ PAST THAT

ZZZZIPP IS TOTALLY CONFUSED

IS HE THE ONLY PERSON THAT THOUGHT “PACIFIC RIM” WAS GARBAGE?

THE CHARACTERS IN “PACIFIC RIM” WERE WORSE THAN CARDBOARD CUT-OUTS. ONLY CHARLIE DAY WAS ALLOWED TO ACT. RON PERLMAN WAS KILLED JUST AS HE DID THE ONLY INTERESTING THING IN THE ENTIRE MOVIE AND IT MADE WHAT HE’D DONE MEANINGLESS. “MAKO” WASN’T MUCH MORE THAN A DOLL, WHICH WAS A SHAME BECAUSE SHE WAS THE ONLY REAL SPEAKING FEMALE CHARACTER ASIDE FROM THE DOG. THE GUY WHO PLAYED “RALEIGH”‘S ONLY DIRECTION WAS TO HOLD HIS BELT AND SAUNTER. RALEIGH COULD HAVE BEEN MUTE AND THE MOVIE WOULD HAVE BEEN EXACTLY THE SAME, BECAUSE HE NEVER NEEDED TO SPEAK. NO ONE EVER NEEDED TO SPEAK. THE MOVIE MIGHT HAVE BEEN BETTER HAD NO ONE EVER SPOKE

ZZZIPP KNOWS THIS IS AN INANE THING TO SAY BUT YOU COULD HAVE WRITTEN SOME PARTS OF THIS POST ABOUT “SHADOW OF THE COLOSSUS” AND IT WOULD HAVE BEEN MORE INTERESTING. THOSE ARE COLOSSI WORTH INVESTIGATING

SOME OF THOSE COLOSSI ARE REALLY SWEET BUT YOU HAVE TO KILL THEM ANYWAY

THE MIND MELDING WAS REALLY BORING BUT PROBABLY THE MOST INTERESTING PLOT DEVICE

(REALLY, WILLIAM GIBSON LIKED IT? WILLIAM GIBSON?? HASN’T WILLIAM GIBSON DONE MORE INTERESTING THINGS WITH SHARED CONSCIOUSNESS???)

(WILLIAM GIBSON??? REALLY????)

(DID THE MIND-MELD WITH THE KAIJU CHALLENGE THE MOVIE AT ALL? CHARLIE DAY WAS LICKED BY A MONSTER BUT THE MIND-MELD REVEALED THAT THE MONSTERS WERE MONSTERS SO WAS ANYTHING INTERESTING INTRODUCED THERE?)

(ZZZIPP WOULD LOVE TO MIND-MELD WITH AN AMOEBA BUT ALL OF THE AMOEBA HE HAS SOLICITED TURNED HIM DOWN)

(PROBABLY ZZZIPP WAS NOT DRIFT-COMPATIBLE)

THE CGI WAS OKAY

DEL TORO HAD NO BUSINESS DIRECTING THIS MOVIE AND MAYBE HE DIDN’T BECAUSE NO ONE DID

ALTHOUGH DEL TORO IS A GREAT DESIGNER

HE ALSO ORGANIZED THE ACTION WELL VISUALLY

AGH WHY WOULD ANYONE THINK WALLS COULD STOP THOSE THINGS

THE WALLS WERE COMPLETELY UNNECESSARY

ENOUGH ABOUT THE WALLS

ZZZZIPP KEPT WONDERING WHY ANYONE WOULD SPEND SO MUCH MONEY ON OBVIOUSLY USELESS WALLS

COULDN’T THEY HAVE PUT GUNS ON THE WALLS

COULDN’T THEY HAVE MADE THE ENTIRE WALLS OUT OF GUNS

COULDN’T THEY HAVE STAFFED THE WALLS WITH “BLACK PEOPLE” READY TO EXPLODE THEMSELVES IN “AN EXTREMELY DIGNIFIED WAY”

IN THREE OUT OF THE FOUR CURRENT SCIENCE FICTION MOVIES ZZZZIPP WATCHED THIS PAST YEAR A STATELY BLACK MAN HAS TO EXPLODE HIMSELF TO SAVE HUMANITY (MORGAN FREEMAN ONCE AND IDRIS ELBA TWICE)

WHY IS THAT

JUST A COINCIDENCE?

AT LEAST IN “PROMETHEUS” IT SEEMED “EARNED”

AGH ZZZIPP HATES THIS MOVIE SORRY FOR EXPLODING ON THIS POST ZZZIPP KNOWS THIS POST IS NOT NECESSARILY ABOUT THE SUCCESS OF THE MOVIE AESTHETICALLY OR EVEN INTELLECTUALLY BUT ABOUT THE TOTALLY VALID FEELINGS/THOUGHTS YOU HAD WATCHING THIS MOVIE AND THE RESULTING DIGRESSIONS WHICH IS TOTALLY FINE OKAY SORRY AGH

[…] imagine a science-fiction story where humans, instead of being the victims of marauding aliens or Kaiju monsters tearing out of the ocean, are actually the scary ones? In a sense, this is obvious. We’ve […]