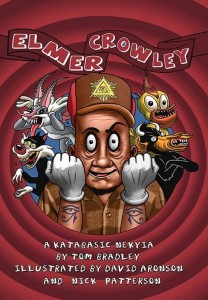

Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia

Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia

by Tom Bradley

Illustrations by David Aronson and Nick Patterson

Mandrake of Oxford Press, 2014

134 pages / $14.99 Buy from Amazon or Mandrake of Oxford

Aleister Crowley is thinking about Germany’s late chancellor:

…my magickal child… who queefed out of my psychic vagina at an unguarded moment…[who] flopped from my left auditory meatus like a menstrual clot with incipient toothbrush mustache…

His mind wanders, logically enough, to Esoteric Hitlerism, the foetal religion presently aborning in Chile. He would like to drop by Santiago and have a chat, perhaps to “glean some intelligence from the gauchos.”

But it’s too late. No more time for the transoceanic jaunts that have varied his long life and kept boredom at bay. The Great Beast 666 happens to be on his death bed. Chapter One is over, and he dies.

Chapter Two begins as follows:

So, let’s sort this out, shall we?

In those seven words you have the essence of this particular historical figure: unkillable inquisitiveness, unshakable aplomb in the sort of psychic circumstances that drove so many of his apprentices and fellow magi insane. Of Crowley’s many fictionalizations, this novel gets best into his head. Erudite, prideful, lascivious, funniest man of his time, and the mightiest spiritual spelunker–he speaks and shouts from these pages as clearly as he did in his Autohagiography, which is paradoxical, given the irreal setting of Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia.

Now that his mortal coil has been shuffled off, Crowley doesn’t know quite what to expect. He has mastered the world’s ancient funerary texts as thoroughly as anyone who ever lived, but fundamental questions remain. Will he be privileged to climb the sevenfold heavens promised by the Gnostics? Will his eyes be offered a luminous series of Tibetan liminalities, clear and smoke-colored?

Apparently not.

Something else materializes and looms up, rather more architectural. It appears the Egyptians came closer than anyone to getting it right.

Crowley’s ghost has been deposited in the Hall of the Divine Kings, as described in the Nilotic Book of the Dead. Of course, our hubristic Baphomet assumes that he’s about to be greeted as a peer by the immortal gods, “the soles of whose sandals are higher than ten thousand obelisks stacked end-to-end.”

But, no, they brush him off like a midge. He’s expected to supplicate like any run-of-the-mill dead person, to have his demerit counterpoised in the balance against a feather. Godhood denied, our high adept has been doomed to reenter the tedious cycle of rebirth. Injured pride, disappointed expectations, the prospect of boredom–these have never sat well with Thelema’s Prophet-Seer-Revelator. He’s about to start behaving badly. (A signal for us to stand well back and shield our eyes and ears.)

If he must return to the rigmarole of existence, it will be on his own terms. Exercising his prerogative as a magus of the highest accomplishment, Aleister Crowley will pick and choose his next carcass. He cold-shoulders the Divine Kings and calls forth Baubo, the headless Greek comedienne-demoness. Her job is to whisper filthy jokes to the peregrinating monad, to get it into a “meaty mood” before it gets stuffed, yet again, among female intestines.

Russian Novels

Russian Novels Manual for Extinction

Manual for Extinction My Enemies

My Enemies

Dept. of Speculation

Dept. of Speculation

We All Sleep in the Same Room

We All Sleep in the Same Room Made To Break

Made To Break