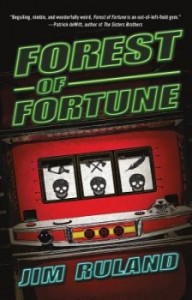

Forest of Fortune

Forest of Fortune

by Jim Ruland

Tyrus Books, July 2014

288 pages / $24.99 Buy from Amazon

In his 1998 documentary Advertising and the End of the World, Sut Jhally defines culture as the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. He further points out that the primary storytellers in our culture—the ones who have the most prominent voice in articulating our value and belief systems—are advertisers. It’s an elegant point, so seemingly simple that its depth can be lost without a few moments to meditate on it.

Most discussions of advertising itself in our culture are limited to the question, “Did that particular advertisement inspire me to purchase that particular commodity?” It’s a feckless question. Jhally notes that the answer to it may be relevant for the people selling the commodity, but it has little relevance to everyone else. Instead, we should be asking ourselves, “What’s the deep-seeded impact of the overwhelming wave of advertising that crashes on us every day?”

What we, as readers and/or writers of novels, don’t discuss much is the relationship of our medium to advertising. Novels are the one contemporary media that is not and can not be saturated with ads. (At least that’s true for the paper ones.) This is one of the reasons I read so many novels. This also leads to one of the great challenges for novelists: to wedge their little story into a culture besieged by several thousand daily advertisements.

Jim Ruland’s recent novel Forest of Fortune is one of those little stories consciously wedging itself into the conversation about advertising. It treads upon similar ground as Jhally’s documentary, yet does so in a tone that allows the reader a bit more freedom in her interpretations. Jhally’s tone is clear from it’s very title: Advertising and the End of the World. Nothing spells doom like that. Ruland also demonstrates his approach early, but in a much more subtle fashion. One of his protagonists, Pemberton, checks into a rundown motel with weekly and monthly rates below the forty-dollar nightly rate. The clerk gives him a sales pitch about one of the rooms. Pemberton is hyper-aware of what’s going on. “A copywriter by trade, [he] knew brochure copy when he heard it, yet was seduced all the same.”

Again, it’s a simple, elegant way of introducing a deep point. Pemberton’s reaction matches a very common one in our culture. We’re often seduced by advertising, untroubled by the knowledge that we’re being lied to, uncritical of the alternate reality it sells. We want the story regardless. In almost every case, it’s the story we purchase. The commodity is just the bi-product, something we’ll keep around until the story loses its luster.

The setting of novel further illustrates this relationship with advertising and consumer commodity culture. It takes place in a fictional California town called Falls City. The name is probably more literary play then heavy handed symbolism. Pemberton arrives there and thinks, “False City, indeed.” It’s a fun way of sending a reader away from the falsity promised by the more specific setting of the novel, Falls City’s Thunderclap Casino.

Thunderclap is run by the fictional Yukemaya tribe. It’s a refuge for those who have bought into commodity culture’s promise that we’re always one purchase from happiness, one bet from hitting the jackpot that will let us make that purchase. It’s a place where the lives of the book’s three protagonists—Alice, Pemberton, and Lupita—intersect without really interacting. Alice is a Native American (though not Yukemaya; not part of a tribe that has a casino) slot technician whose epileptic seizures are sending her life into a downward spiral. Pemberton is a copywriter whose drinking and cocaine abuse is sending his life into a downward spiral. Lupita is a war widow whose gambling addiction is sending her life into a downward spiral. Forest of Fortune, then, is the story of their downward spirals. As Alice’s name and the Lewis Carroll epigraph hint, the novel follows a trajectory similar to Alice in Wonderland. The characters tumble into their alternate realities. They meet bizarre characters and encounter situations that elude their comprehension. Look closely enough, you may find a White Rabbit, a Mad Hatter, a Queen of Hearts, and maybe some other character type.

It’s a crime novel, as well. It’s not a crime novel based on Alice in Wonderland. Something like that sounds awful.

There’s also a ghost. Kind of.

The novel is divided into four sections: Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fire. Each section is introduced by a young woman who lived in the eighteenth century. She also ends the novel. She is a spirit that appears to Alice, Pemberton, and Lupita. Her visits are opaque to both the characters and the reader. She could be a hallucination from Alice’s seizures or Pemberton’s drug abuse or Lupita’s exhaustion. She could be real. Either way, she is neither a spirit guide nor a demon. Fitting in with the tone of the novel, the spirit is more balanced, a way of looking at issues from a different perspective.

More than the downward spirals and the ghost, the characters are linked by their loneliness and depression. This brings us back to advertising.

In his documentary, Jhally discusses happiness surveys. He says that sociologists have performed a host of studies examining what people really want out of life. These studies typically find the same things. People want social interactions. We want good family relationships, a healthy love life, mutually rewarding friendships. We want a certain amount of autonomy and free time that’s genuinely free of work to enjoy these relations. All of these things are things the marketplace cannot give us. In most cases, the marketplace hinders our ability to have the things we genuinely want. It seems a little obvious. If we really wanted consumer commodity culture, the marketplace wouldn’t have to spend billions of dollars a year and pummel us with thousands of ads a day to convince us we did.

In their downward spirals, Lupita, Pemberton, and Alice are exactly what the marketplace needs. For Lupita and Pemberton in particular, their vices are advantageous for Thunderclap. Gambling addictions like Lupita’s are so profitable for the casino that they have a “Rewards Program” that offers addicts like her free food at casino restaurants as long as she keeps dropping all her money into the games. The benefits of Pemberton’s excesses aren’t quite as obvious. Still, he wouldn’t have brought his significant copywriting talents to this casino at the end of the advertising world if his drunken and coked-out behavior had left him with other options. The CEO of the casino rewards him for this by chopping out a line. It’s not thick enough to really get Pemberton high. It’s just enough to keep him working. As for Alice, well, she’s an interesting and wonderfully complex character. I hate to reduce her epilepsy to a symbol because Ruland does so much with it in the novel. Nonetheless, all this conspicuous consumption is literally giving her fits.

In their more honest moments, the characters recognize that the excess of consumer commodity culture is destroying them. Lupita’s family continually tries to draw her back into their lives. She finds herself in a tug-of-war between her addiction and her desire to return to the fold. Alice, also, feels herself slowly dying behind a desk at the casino. She watches the cleaning staff and, as Ruland writes, “She envied their camaraderie, a distant recollection from her earliest memories on the rez. Now look at her: no family, no tribe, no nothing.” Pemberton’s loneliness is articulated the most clearly. At one point in the novel, he encounters a recently-laid-off colleague in the stairwell:

Pemberton tried to conjure up some words to console her and failed, which was unacceptable. Words were Pemberton’s forte. But this wasn’t a pitch or a concept, but a human being, a person in distress. He should be able to reassure her somehow, to find the words that would put her mind at ease, but all he could think about was the line of cocaine he would reward himself with when he got back to his cabin.

This is perhaps Ruland’s most direct engagement with the problem of advertising as our chief cultural storyteller. The copywriter learns that when he has to say something genuinely meaningful, he doesn’t have the words. He’s never learned to speak with depth or honesty.

My favorite thing about Forest of Fortune is the gentle hand that Ruland applies to his characters, his themes, and his setting. It would be easy to write the protagonists’ freefalls as moral instructions for the dangers of addiction, or to write about advertising as a catalyst destroying our society, or to treat the casino as a bleak, exploitative place. But Forest of Fortune is not cautionary tale. Ruland seems undecided what he thinks about all these issues. He shares his exploration with us and leaves the conclusions up to his readers. The result is a rich novel full of humor and darkness.

***

Sean Carswell is the author of five books. His most recent novel, Madhouse Fog, was published by Manic D Press in the summer of 2013. He is an assistant professor of writing and literature at California State University Channel Islands. You can read more by him at seancarswell.org.

Tags: Forest of Fortune, Jim Ruland

enjoyed this, thanks