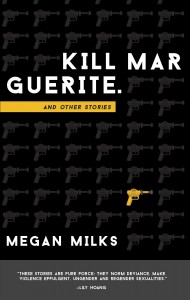

Kill Marguerite and Other Stories

Kill Marguerite and Other Stories

by Megan Milks

Emergency Press, March 2014

240 pages / $15.95 Buy from Amazon or Powell’s

The possibility of Sweet Valley High twins Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefield having incestuous sister-sex with each other never occurred to me when I was a kid and living for those books, even though half the joy of reading them was a desire for violation when faced with all that phony perfection. I always wanted something sexual or terrible to happen, more than a kiss or someone having her bikini top untied in the pool. (The other half of the appeal was jealousy—oh to be 5’6”, blond, and have sparkling aquamarine eyes and a twin sister! Pulchritude amplified.)

So, I am grateful to author Megan Milks, who in her debut story collection, Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, writes in a letter from Elizabeth to Jessica, “I want to spend the evening watching you get yourself clean. I want to shave my head and lie in bed with you all day long. I want you to tell me you love me more each time you look into my eyes. Tell me I’m what your hands were made for, what your mouth was made for.” It’s hilarious, wonderful, mixed-up, and just how I–and probably all the other dirty-Barbie-players out there–feel about these icons. Do we want to be them, fuck them, destroy them? All at once?

Decades after being obsessed with the books, all I had to do was see the story title “Twins” and read the first words “Dear Jessica,” to know just who it was about. The letter ends with Elizabeth entreating Jessica to break down the wall between their bedrooms and collapse the distinction between them, ends on the word “collapse,” actually, a nice touch that’s been kicking around in my head since reading the story last week. The Sweet Valley girls are collapsed into all of us, a bit of gender-identity DNA that, in the second Sweet Valley story in the collection (“Sweet Valley Twins #119: Abducted!”), runs amok in brainless automated loops.

Milks’s debut from Emergency Press is full of such lovely, thought-provoking arrangements of form and content. These are genderqueer girl stories of the most awesome kind, taking the basic narrative of boys, youth, sex and identity, scrambling them with their influences (pop music, porn, sexual fantasy, teen magazines and books, even video games), and then destroying them in gory pornographic explosions.

For example, the story where a young woman has sex with a giant slug, after going on what seems like a bad internet date. It’s hard to tell what the date is like, since the narration shows us primarily her violent S/M fantasies while the date drones on. (“It is a good thing she wore her bitch boots tonight. It is a good thing she dressed prepared. She will take out her pocketknife and flip up the knife part and she will tickle him with the blade slowly, deliberately…. At her command he will get on his hands and knees and enjoy the rug burn, you pathetic motherfucker. Patty is a vicious cunt in bondage gear, with a whip and not afraid to use it, slave.”). She secretly orgasms while kissing him (his tongue is described as being like a slug) and then goes home, where the narrative takes an unapologetic turn into the ero-guro, and she fucks a real slug.

Repulsive, hilarious, hard-to-read, not-hot, yet I keep thinking about it.

“As he moves forward, he shoves her camisole down, the thin straps breaking, and flattens both breasts with his weight, his belly gripping and releasing her nipples rhythmically.”

“Slug kisses Patty until Patty can’t breath. Slug is in her nostrils and in her mouth. Slug’s mucous drips down her throat and fills her lungs.”

Finally Patty turns into a slug and they fuck with two cocks, slug-style, hanging from a tree.

I am of the sensibility to think that the awesomeness of this needs no explanation or further justification. But as someone who writes some ero-guro myself, I think/suspect that there will be an American renaissance of this weird-o Japanese genre, probably is already, and that contemporary ero-guro is a response to the pornification of sex. Displacing sex into someplace unusual is a way to make it visible without falling into the conventions of porn, which, through sheer weight of cliché, now make so much about sex invisible. Also, in another sense, even when it’s sexy, porn is gross. A masturbatory foray onto Google brings up the equivalent of a face-full of slug, once you click the image button, before you find the photos you like. We’re all doing it, so why not take the slug and work it in?

On the most basic level, though, I love this story because everything about it undermines the norms of dating and heterosexual sex.

Every story in the collection has some similar innovation, usually a structural or formal way to present the familiar in a new light. In “Kill Marguerite,” the title story, heroine Caty is in a middle-school-hell of BFFs, mean girls, and bullying, along with rope swings, sucking face, spelling bees and “fat little blubbery boobies.” The surprise is that it’s written like a video game, where on successive screens Caty is killed by a neighbor’s mini-van while she’s riding her bike, dropped into a reservoir where she “hits her head on a rock and there she goes, one of her hearts explodes,” and so on. The usual social mayhem is much improved by jet-packs, grenade launchers and the humorous use of chimes.

The premise reminds me, slightly, of Trisha Low’s The Compleat Purge which, as compendium of her yearly suicide notes, is another book where the heroine dies at the end of every chapter. If this is something bubbling around in the collective unconscious, it feels like an accurate representation of identity for the fragmented, multiple-incarnation lifestyles of Internet-age humans. The video-game violence in “Kill Marguerite” also gets at the emotional reality of middle school, where a humiliation in front of popular kids can truly feel like a death sentence. (Not that any such thing ever happened to me, or like I’d know).

Another way Milks realistically ruptures identity or, to put it another way, messes with the rules of fictional narrative, is the authorial intrusions in some story lines. Milks plays fast and loose with the third wall, addressing the reader, lying, writing dreams. In “The Girl With the Expectorating Orifices,” she says, “One night the woman whose body was a citadel did not text me back. Then the woman whose body was a citadel texted me back. I write this to make it happen. She has not texted me back but I want her to. To make the story real. And it worked. She has texted me back and I have texted her back and so on.” The story is the real thing, maybe the only thing, and by making it up, we make it true. We also speak more honestly to our reader (or achieve the illusion thereof) when we admit there’s an author back there, telling stories.

No one could realistically rupture anything, or speak meaningfully about modern identity, without sampling—narrative, myth, plays, other books, pop songs, video games, popular media, fiction, friends’ stories, memoir—and Milks uses all of these forms. In addition to her wonderful destruction of Sweet Valley High, there’s a collection of queer-culture vignettes from friends based on the Seventeen magazine Traumarama column (with an extreme tampon anecdote so revolting I might never forget it), that again reinvents the original. As a Seventeen reader, I found the column to be generic and conservative in its predictable hetero dilemmas (eeek! a boy! I’m embarrassed! what if I menstruate near him!?), but seen in the light that gay kids are just as goofy and body-phobic as straight kids, the column becomes the reassuring and equalizing presence it was meant to be.

The sampling is part of a deliberate strategy of genre-mashing, a bold ploy to collapse the walls between everything, not just Elizabeth and Jessica’s rooms. Can you put Seventeen and Sweet Valley High in the same collection as a story about slug-fucking, and a play starring Odysseus (the story “Circe”)? Can you go allegorical and unreal in one story, and just plain normal in another? (“Floaters” about an asshole comedian picking on his girlfriend, was the only story that seemed to be set in plain-old-reality.) I liked the concept, but wasn’t convinced that all the mash-ups worked. As a fan of rule-breaking, I hate to say that there are rules–there aren’t, really–but there is a point at which dropped threads stop resonating at other levels, and you’ve just got a mess. Some of the outliers, like “Circe”, “Floaters” and a story with an anthropomorphized wasp and and orchid, didn’t feel coherent with the whole, or incoherently-coherent, either, and I felt like I was being asked to read everything she’d written that she liked, rather than a collection of themed stories. It’s a small point, but one that’s stopping me from raving about the sheer unstoppable genius of the collection as a whole, which was where I thought I was going a few stories in. Basically, though, she had me at “Dear Jessica.”

***

Valerie Stivers is a journalist, fiction writer and reader for The Paris Review. She blogs about her reading list at www.anthologyofclouds.com.

Tags: Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, megan milks, Valerie Stivers

[…] My review of this book just published on HTML Giant. Read it here. […]

jessica was wild and elizabeth was her unscathed mirror image, not necessarily waiting for her, elizabeth was always busy with her own stories, but elizabeth was awake and available after whatever jessica did. you didn’t have to choose. you read one novel after another, over one hundred of those novels, hoping each time jessica will lose her virginity.

Exactly! People will read forever with that kind of incentive.

[…] HTMLGIANT review Lambda Literary review The Whimsy of Creation review […]