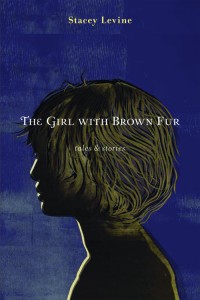

Couched within the strange fables in Stacey Levine’s latest story collection The Girl with Brown Fur are recognizable hurts and self-defeating desires. The way she writes about such things is what makes her fiction the elegant, precise and transcendent wonderland it is. For instance, in the story “The Girl,” the narrator sees a young girl on a leash in the hallway of a hotel, and determines to steal her. As we enter the mind of a child-abductor, we register the obsessive thinking, the cagey strategizing – it’s distasteful, ominous. Then a chance remarks reveals the narrator is a woman, one who has always nursed “the wish to transform into someone else, a different kind of body, to find another story in which to live.” Clearly she is appropriating the girl as way to do this, and the urge is as uneasily recognizable as it is licentious. The story plays with power dynamics in a new way – the animalistic qualities the narrator projects onto the girl (the one with brown fur) make a subtle point about exploitation but also tilt the story into poetry.

Couched within the strange fables in Stacey Levine’s latest story collection The Girl with Brown Fur are recognizable hurts and self-defeating desires. The way she writes about such things is what makes her fiction the elegant, precise and transcendent wonderland it is. For instance, in the story “The Girl,” the narrator sees a young girl on a leash in the hallway of a hotel, and determines to steal her. As we enter the mind of a child-abductor, we register the obsessive thinking, the cagey strategizing – it’s distasteful, ominous. Then a chance remarks reveals the narrator is a woman, one who has always nursed “the wish to transform into someone else, a different kind of body, to find another story in which to live.” Clearly she is appropriating the girl as way to do this, and the urge is as uneasily recognizable as it is licentious. The story plays with power dynamics in a new way – the animalistic qualities the narrator projects onto the girl (the one with brown fur) make a subtle point about exploitation but also tilt the story into poetry.

This is Levine’s genius – to make her points allusively, in an allegorical code, one that nevertheless always feels down-to-earth and revealing of very real pockets in the human psyche. In an interview included with the press package of her new collection, she says: “It wouldn’t mean anything to say outright: ‘He was feeling really anxious because he had always been criticized by his father.’ But it does mean something for me to tell how that would feel, to try to share that experience in a new way.” The technique she has developed for doing this leads her into sometimes surreal and hilarious allegories – about mass production work in a sausage factory (“Sausage”), for example, or a brother and sister who marry each other, with their parents’ approval, and incite wrath only when they want to move out of the family house.

Her characters are fragile and embattled beyond what is normally conceived. Small matters register like a thunderclap; in “Milk Boy,” Levine writes of the eponymous character: “If only he were a hellion, but he was not. Music made him fall over because it was too strong.” Every sphere is troubled for Levine’s characters – from selfhood to the bewildering encounter with an Other to the massive, frightening institutions of marriage and work. As in Kafka, these citadels of adult stability are clouded with timidity and confusion. Nothing seems simple, nothing works clearly. In “The Wedding,” a bride collapses at her ceremony and is borne away to languish under the care of a nurse, who tells her, cryptically, that she has been married since the day she was born. The bride lies on the floor in dejection: “There was a taste of metal to the air. There was an absence of liberty that one could not destroy.”

That absence of liberty is one of Levine’s subjects. As in her novel Frances Johnson, the stories in GWBF reveal that conformity is one of the main blights on the characters. Conformity not only dwarfs freedom of expression – it renders the mental landscape colorless. One of the witty themes of Levine’s work is the idea that there is barely a language in which to pursue questions of identity, so thoroughly has that terrain been colonized by self-help truisms and other banalities of our day. “And You Are?” brilliantly explores this idea – in this story, two women, Janice-Katie and Mrs. Beck, enter into a difficult, quarrelsome relationship. Both are in late middle age, but still struggling with questions of self-definition. Janice-Katie adheres to self-help-era philosophies: “Janice-Katie went out each day, as she felt she should.” In this prescribed way, she attempts to pin down her troublesome existence. “The good side of life was simply better, Janice-Katie told [her friends], though there were sides to life that were neither good nor bad; there were sides that were both, too; there was yet another side that no one could seem to express, and though there should have been no further sides to life, unfortunately, there were.”

This kind of agonized (and very funny) parsing is typical of Levine’s characters, though they’re capable of becoming upset over much less fundamental matters. At any rate, the two women spar over all manner of things big and small and finally (improbably) agree to make a trip to their local sports stadium, where the counterman at the snack bar asks them to go find a bottle of mustard. After being annoyed by everything preceding, the two women find nothing irritating in this request and leave on their errand in a rare moment of accord. What happens next lifts the story into a beautiful dream state – the women begin to run across the field and, as Levine writes the scene, each seems lofted into a singularly harmonious stratosphere, for once not fighting each other or themselves: “The wind dragged in [Janice-Katie]’s ears as she moved; the stadium floated past. Mrs. Beck pulled a tissue from her pocket and, barreling along, blew her nose and wiped wind-induced tears from her face.”

This is both lovely and screamingly funny, two qualities often found in Levine’s fiction. It is absurd and hilarious that these two discontented older women, who have so little to celebrate, find commitment to the moment in an errand to get a bottle of mustard. Is it perhaps in such moments of particularity that we do feel more harmony with existence? Sometimes? But that feels like it’s stretching it – Levine’s imagination is so fine and delicate that to pin it down to any generality seems like a gross misprision.

If “And You Are?” explores the difficulties of relations between self and other, “Sausage” returns Levine to a theme she explored in her first novel, Dra__ — the depersonalizing nature of work. In a Kafkaesque setting, this time a sausage factory, she describes a feverishly devoted workplace where employees strive to outpace each other as they produce sausages by cycling on mounted bicycles. The narrator writes about his zeal for the work in this marvelous passage:

Throwing my head back, hooting with relish, raising a rough, corrugated stick we often used to show purpose and excitement, I began to pedal backward…. Surely I was good, and produced properly at all moments – this being the pride and requirement of our factory and nation.

But then it turns out the narrator’s ardor is the wrong kind – he is accused of being “theatrical,” unable to see life as it really is. This is a typical setback in Levine’s fiction – there is great confusion regarding emotional demands, whether those of a workplace or any other situation. Characters frequently accuse each other of dishonesty; “Sausage” ends with the narrator’s paranoid fantasy of the “leaders” attacking him for his entire psychic apparatus:

…let’s now talk, and examine your mind as it is discussed in texts, the ways you misperceive the world due to your own defensiveness, the way you project feelings about yourself into the world of work…

Again, Levine takes a mundane element of regular life – a workplace critique – and wittily casts it with the probing intensity of a psychoanalytical case study. Sometimes the dissection of motives her characters engage in can seem cruel or obsessive from a common-sensical point of view, but it also seems like the articulation of a level of pain most writers can’t access. With their wild accusations of each other, Levine’s characters sum up the blundering and botching of human relations that goes on all the time, but is usually written about in a much more obvious way. Levine penetrates into the heart of strangeness that hangs between people, despite reflexive efforts to please and placate each other.

Another of Levine’s subjects is our desires and the paradoxical way they can lead us into the most perfect dissatisfaction. “The Cats” is about a woman who pays for an expensive procedure to have her beloved kitten, Sis, cloned. This mildly absurd scenario is immediately fashioned into something far more deeply troubled by Levine – the new kitten turns out to be a disappointment, not a carbon copy but with annoying traits of difference: “…the kitten seemed not the duplicate, but the opposite, of Sis.” The cloned kitten also develops all kinds of physical problems, in a hilarious metaphor (perhaps) for reality versus the glossy perfection we’re sold by marketing, but she slowly wins the woman over until she finds herself losing her affection for her original cat. Again, this is absurdly funny – instead of being replicated, love has been dissipated and perverted in an excess of misguided effort.

Levine’s stories take place at one remove from anything identifiable as contemporary life – there are almost no brand names, and no pop culture references or mentions of life in the cyber age. But despite the otherworldly, sometimes mittel-European atmosphere, these stories are rooted in the same personal stuntedness and uneasiness David Foster Wallace wrote about in Infinite Jest. That novel insisted on the troubling reality of children mysteriously crippled by the bright, self-congratulatory theorizing of their educated parents – its subject, beneath a vast structure of plot and satire, was abuse of children by adults. The theme of abuse also runs like an underground stream beneath Levine’s work – there is a sense that her characters are offered no emotional nurturing from either the culture or their original caregivers. If there has been neglect on the home front, there is no succor in the barrage of conformist messages our culture produces on an hourly basis; Levine’s characters experience psychic death in the vacuous atmosphere and don’t have the ego strength to create inner worlds of their own. So they teeter in blankness, snarling at each other, protecting small, meaningless boundaries. To spend time with them is to be confounded, haunted, amused and forever changed.

***

Kristy Eldredge is the writer and director of the Robot Secretary video series, and head writer for the upcoming comedy series The Idealistic Prism. She reads, writes and writes about contemporary fiction whenever time permits.

Tags: stacey levine, starcherone books, the girl with brown fur

tinyurl.com/297sxrk

wow i want to read this book!! beautiful review kristy, i can hear your passion for literature in every line. if only you could make a living from readin and writin…shine on, alison

tinyurl.com/297sxrk

http://www.vipshopper.us

http://www.vipshopper.us

About the Girl with Brown Fur whatever you published here seems to me complicated conception though. thanks!

practice stock trading

The Girl with Brown Fur by Stacey Levine | HTMLGIANT