John Cheever fiction published in The New Yorker

“Buffalo” – June 22, 1935 (pp. 66-68)

“Play A March” – June 20, 1936 (pp. 20-21)

“A Picture for the Home” – Nov. 28, 1936 (pp. 80-83)

“In the Beginning” – Nov. 6, 1937 (pp. 77-80)

“Treat” – Jan. 21, 1939 (pp. 50-51)

“The Happiest Days” – Nov. 4, 1939 (pp. 15-16)

“It’s Hot in Egypt” – Jan. 6, 1940 (pp. 20-21)

“North of Portland” – Feb. 24, 1940 (pp. 20-21)

“Survivor” – Mar. 9, 1940 (pp. 54-56)

“Washington Boarding House” – Mar. 23, 1940 (pp. 23-24)

“Riding Stable” – Apr. 27, 1940 (pp. 20-21)

“Happy Birthday, Enid” – July 13, 1940 (pp. 15-16)

“Tomorrow Is a Beautiful Day” – Aug. 3, 1940 (pp. 15-16)

“Summer Theatre” – Aug. 24, 1940 (pp. 45-48)

“The New World” – Nov. 9, 1940 (pp. 17-19)

“Forever Hold Your Peace” – Nov. 23, 1940 (pp. 16-18)

“When Grandmother Goes” – Dec. 14, 1940 (pp. 68-75)

“Hello, Dear” – Feb. 15, 1941 (pp. 20-21)

“The Law of the Jungle” – Mar. 22, 1941 (pp. 16-18)

“There They Go” – July 19, 1941 (pp. 17-18)

“Run, Sheep, Run” – Aug. 2, 1941 (pp. 50-52)

“Publick House” – Aug. 16, 1941 (pp. 45-49)

“These Tragic Years” – Sept. 27, 1941 (pp. 15-17)

“In the Eyes of God” – Oct. 11, 1941 (pp. 20-22)

“The Pleasures of Solitude” – Jan. 24, 1942 (pp. 19-21)

“A Place of Great Historical Interest” – Feb. 21, 1942 (pp. 17-19)

“The Shape of a Night” – Apr. 18, 1942 (pp. 14-16)

“Goodbye, Broadway—Hello, Hello” – June 6, 1942 (pp. 19-20)

“Problem No. 4” – Oct. 17, 1942 (pp. 23-24)

“The Man Who Was Very Homesick for New York” – Nov. 21, 1942 (pp. 19-22)

“Sergeant Limeburner” – Mar. 13, 1943 (pp. 19-25)

“They Shall Inherit the Earth” – Apr. 10, 1943 (pp. 17-18)

“A Tale of Old Pennsylvania” – May 29, 1943 (pp. 20-23)

“The Invisible Ship” – Aug. 7, 1943 (pp. 17-21)

“My Friends and Neighbors All, Farewell” – Oct. 2, 1943 (pp. 23-26)

“Dear Lord, We Thank Thee for Thy Bounty” – Nov. 27, 1943 (pp. 30-31)

“Somebody Has to Die” – June 24, 1944 (pp. 27-28)

“The Single Purpose of Leon Burrows” – Oct. 7, 1944 (pp. 18-22)

“The Mouth of the Turtle” – Nov. 11, 1944 (pp. 27-28)

“Town House” – Apr. 21, 1945 (pp. 23-26)

“Manila” – July 28, 1945 (pp. 20-23)

“Town House—II” – Aug. 11, 1945 (pp. 20-25)

“Town House—III” – Nov. 10, 1945 (pp. 27-32)

“Town House—IV” – Jan. 5, 1946 (pp. 23-28)

“Town House—V” – Mar. 16, 1946 (pp. 26-30)

“Town House—VI” – May 4, 1946 (pp. 22-27)

“The Sutton Place Story” – June 29, 1946 (pp. 19-26)

“Love in the Islands” – Dec. 7, 1946 (pp. 42-44)

“The Beautiful Mountains” – Feb. 8, 1947 (pp. 26-30)

“The Enormous Radio” – May 17, 1947 (pp. 28-33)

“The Common Day” – Aug. 2, 1947 (pp. 19-24)

“Roseheath” – Aug. 16, 1947 (pp. 29-31)

“Torch Song” – Oct. 4, 1947 (pp. 31-39)

“O City of Broken Dreams” – Jan. 24, 1948 (pp. 22-31)

“Keep the Ball Rolling” – May 29, 1948 (pp. 21-26)

“The Summer Farmer” – Aug. 7, 1948 (pp. 18-22)

“The Hartleys” – Jan. 22, 1949 (pp. 26-29)

“The Temptations of Emma Boynton” – Nov. 26, 1949 (pp. 29-31)

“Christmas Is a Sad Season for the Poor” – Dec. 24, 1949 (pp. 19-22)

“The Season of Divorce” – Mar. 4, 1950 (pp. 22-27)

“The Pot of Gold” – Oct. 14, 1950 (pp. 30-38)

“The People You Meet” – Dec. 2, 1950 (pp. 44-49)

“Clancy in the Tower of Babel” – Mar. 24, 1951 (pp. 24-28)

“Goodbye, My Brother” – Aug. 25, 1951 (pp. 22-31)

“The Superintendent” – Mar. 29, 1952 (pp. 28-34)

“The Chaste Clarissa” – June 14, 1952 (pp. 29-33)

“The Cure” – July 5, 1952 (pp. 18-22)

“The Children” – Sept. 6, 1952 (pp. 34-45)

“O Youth and Beauty!” – Aug. 22, 1953 (pp. 20-25)

“The National Pastime” – Sept. 26, 1953 (pp. 29-35)

“The Sorrows of Gin” – Dec. 12, 1953 (pp. 42-48)

“The Five-Forty-Eight” – April 10, 1954 (pp. 28-34)

“Independence Day at St. Botolph’s” – July 3, 1954 (pp. 18-23)

“The Day the Pig Fell into the Well” – Oct. 23, 1954 (pp. 32-40)

“The Country Husband” – Nov. 20, 1954 (pp. 38-48)

“Just Tell Me Who It Was” – Apr. 16, 1955 (pp. 38-46)

“Just One More Time” – Oct. 8, 1955 (pp. 40-42)

“The Bus to St. James’s” – Jan. 14, 1956 (pp. 24-31)

“The Journal of an Old Gent” – Feb. 18, 1956 (pp. 32-59)

“The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” – Apr. 14, 1956 (pp. 42-71)

“Miss Wapshot” – Sept. 22, 1956 (pp. 40-43)

“Clear Haven” – Dec. 1, 1956 (pp. 50-111)

“The Trouble of Marcy Flint” – Nov. 9, 1957 (pp. 40-46)

“The Bella Lingua” – Mar. 1, 1958 (pp. 34-55)

“Paola” – July 26, 1958 (pp. 22-29)

“The Wrysons” – Sept. 13, 1958 (pp. 38-41)

“The Duchess” – Dec. 13, 1958 (pp. 42-48)

“The Scarlet Moving Van” – Mar. 21, 1959 (pp. 44-50)

“The Events of That Easter” – May 16, 1959 (pp. 40-48)

“The Golden Age” – Sept. 26, 1959 (pp. 46-50)

“The Lowboy” – Oct. 10, 1959 (pp. 38-42)

“The Music Teacher” – Nov. 21, 1959 (pp. 50-56)

“A Woman Without a Country” – Dec. 12, 1959 (pp. 48-50)

“Clementina” – May 7, 1960 (pp. 40-48)

“Some People, Places, and Things That Will Not Appear in My Novel” – Nov. 12, 1960 (pp. 54-58)

“The Chimera” – July 1, 1961 (pp. 30-36)

“Seaside Houses” – July 29, 1961 (pp. 19-23)

“The Angel of the Bridge” – Oct. 21, 1961 (pp. 49-52)

“The Brigadier and the Golf Widow” – Nov. 11, 1961 (pp. 53-60)

“The Traveller” – Dec. 9, 1961 (pp. 50-58)

“Christmas Eve in St. Botolph’s” – Dec. 23, 1961 (pp. 26-31)

“A Vision of the World” – Sept. 29, 1962 (pp. 42-46)

“Reunion” – Oct. 27, 1962 (p. 45)

“The Embarkment for Cythera” – Nov. 3, 1962 (pp. 59-106)

“Metamorphoses” – Mar. 2, 1963 (pp. 32-39)

“The International Wilderness” – Apr. 6, 1963 (pp. 43-47)

“Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin” – Apr. 27, 1963 (pp. 38-41)

“An Educated American Woman” – Nov. 2, 1963 (pp. 46-54)

“The Habit” – Mar. 7, 1964 (pp. 45-47)

“Montraldo” – June 6, 1964 (pp. 37-39)

“Marito in Città” – July 4, 1964 (pp. 26-31)

“The Swimmer” – July 18, 1964 (pp. 28-34)

“The Ocean” – Aug. 1, 1964 (pp. 30-40)

“Another Story” – Feb. 25, 1967 (pp. 42-48)

“Bullet Park” – Nov. 25, 1967 (pp. 56-59)

“Percy” – Sept. 21, 1968 (pp. 45-50)

“The Folding-Chair Set” – Oct. 13, 1975 (pp. 36-38)

“The Night Mummy Got the Wrong Mink Coat” – Apr. 21, 1980 (p. 35)

“The Island” – Apr. 27, 1981 (p. 41)

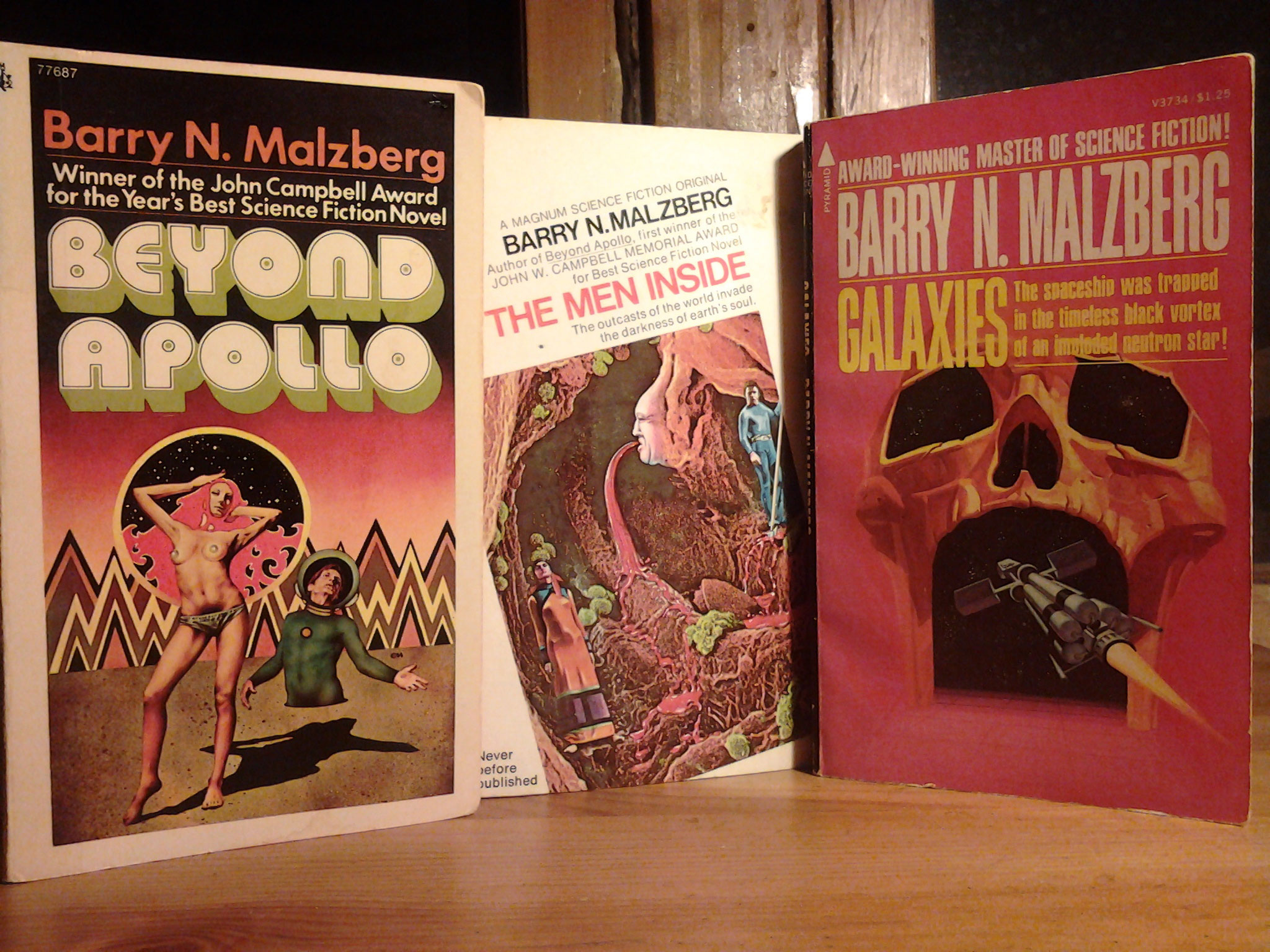

25 Points: 3 Novels by Barry N. Malzberg (Beyond Apollo, The Men Inside, & Galaxies)

Beyond Apollo | 1972, Random House | 156 pages

The Men Inside | 1973, Prestige Books | 175 pages

Galaxies | 1975, Pyramid Books | 128 pages

(Note: all three of these books are out of print, but cheap used copies can be found. In Chicago, I bought Beyond Apollo for $2.95 at Myopic Books (in Wicker Park) and The Men Inside for $3 at Bucket O’ Blood Books and Records (Logan Square). Galaxies I purchased used through Amazon for $1.25 + s/h.)

1. On 15 August 2011, my pal Jeremy M. Davies emailed me and said that I should look for a book called Galaxies by Barry N. Malzberg because it was “seriously beyond belief.”

I’m ashamed to say it took me until earlier this year to pick up a copy and read it. However, once I got started, I finished it under 24 hours.

2. Barry N. Malzberg was born in 1939. Since 1968, he’s written at least 66 books, if not more. (He’s worked under ten different names that I know of, which complicates compiling a full list.) Dozens of them are science-fiction novels—at least in theory. He’s also written story collections, essay collections, movie novelizations, crime novels, and pornography.

3. Galaxies (1975) at first glance tells the story of a young astronaut, Lena Thomas, the sole crew member of the spaceship Skipstone. Her cargo is an immense tank of goo filled with 515 human corpses. It’s the year 3902 and a person can pay to have his/her body ferried into space after death in the hopes that cosmic radiation will revive them.

Midway through the voyage, the Skipstone falls into a black hole, and the majority of the novel’s plot deals with Lena’s attempt to escape the ensuing hallucinatory free fall. During that timeless time she repeatedly dies and is reborn, recalls her lover John, consults with cyborg engineers, and communes with the dead, who have psychically reawakened.

But that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

4. Rather, Galaxies is a work of metafiction, concerned with its own creation, and presented as Malzberg’s notes on how he would write the novel Galaxies, if only he could. (He maintains that the novel is impossible to complete with present knowledge.) As such, most scenes are outlined rather than dramatically depicted. For instance, Chapter 29 begins:

And here could run yet another moody flashback concerning Lena’s relationship with John, dropped in to provide color and poignance, augmenting the mood of despair. Long sexual passages here could alternate with painful streams of consciousness in the present. Sex and space, orgasm and isolation could run counterpoint, and the author’s gifts for irony, which are not modest, would be exhibited to their fullest range. Also, in the traditions of modern science fiction, the sex scenes could be quite titillating, render the novel some extraliterary interest. A construct like this could use all the extraliterary interest it could get.

But even that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

6. Rather, Galaxies is about what science-fiction should look like in the year 1975. Malzberg is surveying contemporary literature and asking: How should science-fiction respond to the then-recent literary experiments of John Cheever, John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Roth, and others?

7. I’m not making this up. On page 48 Malzberg writes:

For instance, as the ship falls, there could be some elaboration on the suggestion that neutron stars might be pulsars which would be most intriguing, if the reader has not been intrigued sufficiently by the notion that all of “life” as we understand it when we glimpse the heavens may be merely an incidental by-product of the cycle of neutron stars.

So there, Cheever, Barth, Barthelme, Oates. What in the collected works would touch that for angst?

8. Malzberg calls those authors out again on page 85:

“Madness,” Lena says, shaking her head, “that’s utter madness,” but the author, busily pulling the handles of this little dumb show, sweating behind the canvas, casting a nearsighted, astigmatic eye every now and then through the cardboard of the set to see whether the audience is paying attention, how the audience is taking all of this, is thinking take that Barth, Barthelme, Roth, or Oates! Pace Bellow and Malamud, and may your Guggenheims multiply, but what have any of you or those unnamed created to compare with this?

9. If I haven’t convinced you yet to spend $2–3 on a used copy of Galaxies, you might as well quit reading now.

April 1st, 2013 / 8:01 am

The Pleasures of Cheever

Some of you might very frequently pick up a book feeling certain that you will like it. This happens to me pretty rarely; usually only when I’ve read the book already, or when it is by Charles Dickens or Virginia Woolf. So it was with particular relish when, still feeling the pang of having no more of Middlemarch to read, I opened The Wapshot Chronicle by John Cheever.

I’d only read Cheever’s stories, which I really love, whether the earlier perhaps more conventional ones or later so-called experiments like “The Swimmer.” Putting aside the question of whether “experimental” is or is not a troublesome descriptor of any art, I don’t think it fits well with Cheever at any stage in his career. One gets the sense with Cheever that he read widely and deeply, probably heavily in Shakespeare and the classics, took what he found useful and then made sentences that were all his own, without giving any thought to fashion and currency.

Sentences like:

We have all parted from simple places by train or boat at season’s end with generations of yellow leaves spilling on the north wind as we spill our seed and the dogs and the children in the back of the car, but it is not a fact that at the moment of separation a tumult of brilliant and precise images–as though we drowned–streams through our heads. We have indeed come back to lighted houses, smelling on the north wind burning applewood, and seen a Polish countess greasing her face in a ski lodge and heard the cry of the horned owl in rut and smelled a dead whale on the south wind that carries also the sweet note of the bell from Antwerp and the dishpan summons of the bell from Altoona but we do not remember all this and more as we board the train.

What Does It Mean to Be a Young Writer Today?

Take our own Ken Baumann. He’s twenty, and already toying with a style, voice, and rhythm all his own–see the newest New York Tyrant for proof. His work is at once strange and familiar, careful and mindful without constraining a sense of freedom which announces the promise of novelty, of a literature which is no longer merely literature. If any of that makes any sense to anyone. What I mean to say is, Ken is a young–very young, college-aged–prose stylist. Perhaps that is a rare feat. Perhaps it is not. But not often does an artist so young fulfill the promise of youth by making it new.

Take Zachary German. He’s twenty-one, I believe, and while he indeed belongs to a certain class of writers, his style, at a very original pace, moves toward a terminal space, a degree-zero. His work has much to say about contemporary art, culture, and values, on both a level of doing and being. In many ways, he walks the talk of a young Camus. He’s twenty-one. How?

I’m nineteen. I strive for an immediate stylism in my work. Whether or not I’m successful I cannot say. READ MORE >

WAYYYBACK MACHINE: Updike & Cheever on the Dick Cavett show

I found this earlier today. Who even knew that Cavett had an NYT blog? Anyway, he somehow got the Times to post a full episode of his show from October 1981, with Cheever and Updike as his guests. I’m not a huge fan of either man–dig Cheever, as far as it goes; basically have never read Updike–but there was something really fascinating about this, and I wound up watching the whole 28-minute clip. Cheever’s voice is amazing. They really don’t make ’em like him anymore. In the post itself, Cavett writes-

True, but that notwithstanding–or perhaps because of it–Cheever is the one to watch for. I love the part where he talks about church, and Cavett tries unsuccessfully to get him to recite the Apostles Creed.

Updike is mostly quiet, and I think very conscious of his role as the young up-and-coming writer. (How could he not be? Cheever points out “I’m old enough to be John’s father.”) He sits back trying to look comfortable for a few long stretches, while Cheever lavishes praise on him, his work, his talent, etc. They also talk about several things we still argue about more or less daily on this website: can you / should you live and write in NYC? What kind of public profile should a writer have? How does reviewing books fit into writing books? Even though you’re famous, will the New Yorker still reject your story if they don’t like it? (Updike: “they should.”) Etc etc. And plus there’s the sheer joy of watching this kind of televsion, delightfully stone-age, with no commercial breaks, cuts to new segments, and almost no graphics. Nothing but smart, decent people talking about stuff smartly and decently: an idea so out-moded and archaic it might just be revolutionary again.

“Everybody is pink.” An Excerpt from The Journals of John Cheever

God bless Blake for putting up with the likes of me. He truly celebrates diversity of tastes and temperments with letting me be a contributor. I love Cheever. I might love his journals as much as his short fiction. (I like his novels a bit less). Here’s an excerpt, a random one, from near the end of his life, when the world starts changing so fast on us, it dizzies us. I often think about aging and dying and how chaos and destruction eventually win our bodies whole. (Thanks Mom and Dad.) This excerpt is one of many strange and heartbreaking sections from his journals that show his delight in language and confusion as to what our time here actually means: READ MORE >

God bless Blake for putting up with the likes of me. He truly celebrates diversity of tastes and temperments with letting me be a contributor. I love Cheever. I might love his journals as much as his short fiction. (I like his novels a bit less). Here’s an excerpt, a random one, from near the end of his life, when the world starts changing so fast on us, it dizzies us. I often think about aging and dying and how chaos and destruction eventually win our bodies whole. (Thanks Mom and Dad.) This excerpt is one of many strange and heartbreaking sections from his journals that show his delight in language and confusion as to what our time here actually means: READ MORE >

Cheever, in his boxer shorts, convinces me to continue writing short stories.

From the essay “Why I Write Short Stories,” which is collected in the Library of America’s upcoming John Cheever: Collected Stories and Other Writings:

To publish a definitive collection of short stories in one’s late 60s seems to me, as an American writer, a traditional and a dignified occasion, eclipsed in no way by the fact that a great many of the stories in my current collection were written in my underwear.

Another selection from the essay:

A collection of short stories appears like a lemon in the current fiction list, which is indeed a garden of love, erotic horseplay and lewd and ancient family history; but so long as we are possessed by experience that is distinguished by its intensity and its episodic nature, we will have the short story in our literature, and without a literature we will, of course, perish.

May you be correct, Cheever. The rest of this very short essay can be found here.