A NEW KIND OF EDUCATION

A Ring of Sunshine Around the Moon

A Ring of Sunshine Around the Moon

by the Students of the Academic Leadership Community

Foreword by Paul Feig

826LA, June 2012

175 pages / $15 Buy from 826LA

&

Mandy, Charlie & Mary-Jane

by Stewart Home

Penny-Ante Editions, 2013

252 pages / $18.95 Buy from Penny-Ante Editions or Amazon

One of the most comic aspects of today’s debate surrounding education and its so-called “reform” is the minimal to nonexistent degree to which the research literature plays in shaping public policy. We have a particularly weird situation in the United States where it was not that long ago when Republican presidential candidates promised, if elected, to obliterate the Department of Education and abolish bilingual support for English Language Learners (ELLs). Is the Tea Party aware of the up to 150 empirical studies during the past 30 years that have detailed a positive link between bilingualism and students’ academic growth? And on the opposite side of the aisle, we have no less weirdly President Obama increasingly citing Race to the Top and South Korea, a nation of test prep factories, as the exemplar model for the United States. How many of our current political leaders are aware of the fact that there simply are no strong indicators for standardized testings’ efficacy? If anything, recent research shows that high-stakes testing actually hinders student growth.

It is precisely against this educational deadlock that I’ve been inspired to use Stewart Home’s many texts and pamphlets to promote students’ language acquisition. Though certain of my colleagues have perceived Home’s work as too obscure and difficult for “at risk” ESL students and English learners of low socioeconomic status, I have found that books like 69 Things to Do With a Dead Princess and Tainted Love are the ideal means of heightening student motivation and introducing academic language into a stale curriculum. After all, what teenager, “at risk” or otherwise, isn’t interested in sex and music? I’ve recently learned, to my surprise, that I am not the first to use the South London born enfant terrible for second language purposes; Tosh Berman’s Japan-born wife used Home’s The Assault On Culture to learn English. As a fond student of USC’s language acquisition expert Stephen Krashen, this comes as no surprise. According to Krashen the one and only task for the language instructor, other than making the lessons comprehensible, is to make the language content interesting. Recently he has even gone as far as to assert that it is not enough to simply make the lessons interesting, the language content must be startlingly compelling, in a word – profound.

Enter Mandy, Charlie, and Mary-Jane. Not unlike Mark Norris’ novel Art School, Home’s newest anti-novel captures the giddy wanderlust of campus life and the heady brew of incompatible concepts and referential chains in those schools where theory has some kind of impact. Though critics and fans alike have been drawn to the nihilistic and morally depraved acts of the main character Charlie, a psychotic cultural studies lecturer who frames a student for arson and detonates a bomb in the immediate aftermath of the 7/7 terrorist attack in London, Mandy, Charlie & Mary-Jane serves a critical function for my college-bound “ESL/English learner” students who are rebuked daily by educational stakeholders on the importance of college as a panacea for all of their economic ills and social difficulties. As Home himself acknowledged in a recent interview with Michael Roth, “[O]bviously universities are basically there to turn people into zombies – so that they can become trusted functionaries of the capitalist system. That said, we all reproduce our own alienation under capitalism, so I’m not saying that people shouldn’t attend or work in universities, just that we should be aware that they are about conformism and anyone who claims that higher education has very much to do with intellectual growth and development is either an idiot or an apologist for capitalism.”

June 24th, 2013 / 11:00 am

On Violence & Red Tales: An Interview with Susana Medina

I met Susana Medina at the inaugural reading of Book Works’ Semina series in June 2008. Her struggle with deafness and affection for Borges made her immediately endearing. Between shots of whisky and glasses of Haut-Medoc, we talked. Chitchat mainly about films and books, but somehow the talk became serious and autobiographical.

Born of a Spanish father and a German mother of Czech origin, she grew up in Valencia, Spain. Her short film Bunuel’s Philosophical Toys, deconstructs the instances of fetishism in the films of Luis Bunuel. Over the years I’ve come to believe that the gap between what Medina has accomplished in her doctoral thesis on Borges, and what her mainstream colleagues have passed off as literary theory, exposes academic discourse for what it is — an imaginary labyrinth without beginning or end that presupposes its own epistemological superiority.

This interview, started March 2011, has been in the making for nearly two years. I spoke with Susana off and on via Facebook.

***

Maxi Kim: Stewart Home recently described your new book RED TALES as “a total shock to mummy porn fans – E. L. James meets J. G. Ballard! Makes both writing and BDSM dangerous once again.” I personally found it much more readable and theoretically latent than much of what passes today for Feminist writing, much more so than even Kate Zambreno’s Heroines. How did this project come to be? What are its origins?

Maxi Kim: Stewart Home recently described your new book RED TALES as “a total shock to mummy porn fans – E. L. James meets J. G. Ballard! Makes both writing and BDSM dangerous once again.” I personally found it much more readable and theoretically latent than much of what passes today for Feminist writing, much more so than even Kate Zambreno’s Heroines. How did this project come to be? What are its origins?

Susana Medina: I like your way of putting it, ‘theoretically latent.’ Red Tales came about through a cluster of concerns. I was interested in fluid sexualities, gender, androgyny, the irrational, compulsions. All the stories are narrated by wayward female narrators. To articulate a defiant female gaze was important for me. In a way, looking at the female nude in Art History, made me want to make all these women speak back. So maybe I became a ventriloquist for these sensual women who seemed so quiet. It was also a reconciliation with narrative, as my first novel, a fragmentary anti-novel, had as its point of departure the most minimalist Beckett. My interest in poetic fragments remained and I intertwined it with fast-moving narrative, so I suppose there is this newly found pleasure in narrative, with the fragment as counterpoint and vessel for interiority, as well as for the fragmentary realities we live. All the stories are conceived as spaces, like art installations. The image was central to all the narratives. I was really interested in American female artists like Cindy Sherman, Jenny Holzer, Kruger, the vanished Cady Noland, in subjectivity and identity as fluid entities… Thank you about the Kate Zambreno’s Heroines reference, which I googled straight away. Like I googled E.L. James when I came across Stewart Home’s blurb, which I thought was nicely confusing. By the way, I hadn’t read JG Ballard at the time –he was later to become one of my favourite writers-, but the connection is there, in terms of a shared interest in the psychopathology of everyday life.

MK: What do you make of Marie Calloway?

SM: I don’t know her. Who is she? Interesting?

MK: Interesting? It depends on who you ask. Like you, she’s interested in fluid sexualities, gender, compulsions, articulating something that approaches a defiant female gaze. She has put out public nude photos of herself with texts that overlap; there may be a parallel here with your project of looking at the female nude in Art History. I am reminded of that last scene in Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009) when all the wayward anonymous females climb up the hill to presumably kill Willem Dafoe.

SM: Googled her and printed an article, but still haven’t quite woken up. She sounds interesting, like Chris Kraus. You’ve worked with her, haven’t you? Or related? Cousins?

TWO OR THREE WAYS TO RESURRECT PHILIP K. DICK

Philip K. Dick: Remembering Firebright

Philip K. Dick: Remembering Firebright

by Tessa B. Dick

CreateSpace, March, 2009 & 2010

228 pages / $15.77 Buy from Amazon

&

Daughter

by Janice Lee

Jaded Ibis Press, 2011

144 pages / Color Ed. $39 Buy from Amazon or Jaded Ibis

B/W Ed. forthcoming Summer 2012

The last thing Philip K. Dick’s work needs is another philosopher’s commentary. After Fredric Jameson’s “synoptic” reading of Dick’s corpus and Laurence A. Rickels’ 400-plus page I Think I Am: Philip K. Dick, it might seem prudent, indeed respectful, to refrain from any further philosophical discussion of PKD. However, after spending some time with Tessa B. Dick’s “memoir” and Janice Lee’s “novel,” I am inclined to discuss a dimension of Dick’s that neither Jameson nor Rickels were able to deal with in their commentaries: namely, the particularly contemporary problem of living without myth. Anthropology tells us that peoples of the past actually believed in their myths; a mythological framework provided by the gods presumably told you how to lead your life and what your ultimate place in the universe was. Now that all of our myths have been more or less discredited by the advent of modernity, how might a viable contemporary myth cope with the disintegrating social edifice and the resulting modern subject who minimally experiences the “death of God”?

We’ll start with a strident way in – that of Daughter’s vision of “the head of a human figure with a terrifying face, full of wrath and threats” appearing to the protagonist “in the sky, on a night when the stars were shining and she stood in prayer and contemplation.” These two elements – the terrifying face of the big Other, and the lost subject in search of meaning and the miraculous – are constants in Philip K. Dick’s biography. In the late seventies, Dick recalled: “There I went, one day [in 1963], walking down the country road to my shack, looking forward to eight hours of writing, in total isolation from all other humans, and I looked up in the sky and saw a face. . . . and it was not a human face; it was a vast visage of perfect evil.” To the psychological impact of such an encounter, Janice Lee supplies a concrete example: “At the sight of it, she feared that her heart would burst into little pieces. Therefore, overcome with terror, she instantly turned her face away and fell to the ground. And that was the reason why her face was not terrible to others.”

April 30th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

REVOLT, SHE SAID

Where Art Belongs

Where Art Belongs

by Chris Kraus

Semiotexte, 2011

160 Pages / $13 Buy from MIT Press

&

Girls to the Front

by Sara Marcus

Harper Perennial, 2010

384 Pages / $15 Buy from Amazon

If you’re invested in the lives and work of girls as cultural agents, then you’ll like Sara Marcus’ Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution and Chris Kraus’ Where Art Belongs. Like certain of my punk obsessed friends, my interest in bands like Bikini Kill and Bratmobile developed in high school during the late 90s. And by then the whole riot grrrl phenomenon in its original incarnation, with Kathleen Hanna front and center at the mic, was more or less dead. By the time I was introduced to Bikini Kill’s first album, the band had already released its final album Reject All American and played its final show in April 1997. Subsequent fans were left to speculate on both the political origins of the band and the interpersonal relationships that constituted riot grrrl as a living, breathing feminism.

September 19th, 2011 / 12:00 pm

AT LAST, SEXUAL SATISFACTION FOR CINDY SHERMAN WITH YOUR BIGGER AND NEWEST ATEMPORAL NETWORK CULTURE!

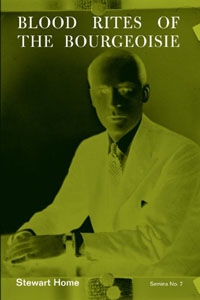

Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie

Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie

by Stewart Home

Book Works, 2010

120 pages / $19.99 Buy from Amazon

&

The New Poetics

by Mathew Timmons

Les Figues Press 2010

112 pages / $15.00 Buy from Les Figues

If you’re anything like me, you’re probably keen on the emergent discourse surrounding our current atemporal, altermodern new media status. Facebook, Flickr, Google, iPad, iPod, Myspace, Youtube, etc, etc: its all grist for contemporary philosophers, and writers too have attempted to capitalize on the ubiquity of Twitter feeds and Facebook updates – with mixed results. Zen literary terrorist Stewart Home and Los Angeles-based poet Mathew Timmons are both authors of recent books that are candidates for an emergent atemporal literature (for lack of a better term); what Home and Timmons have managed to do is to avoid the trap of the ever-expanding rotting mounds and heaps of aspiring internet-based fiction, and needless to say – that trap is the perennial lure of narrative storytelling.

August 1st, 2011 / 12:00 pm