A D Skywalker vs. Darth Higgs

Adam: Last weekend, playing a stray note on my recorder summoned a cyclone that whirled me away to the swamps of Tallahassee. There I impinged on Christopher Higgs and his wife, who lodged me in their spacious Rococo flat (refurbished from a gator-packing warehouse). Over dinner, Chris and I had numerous opportunities to discuss—and to disagree about—the nature of experimental fiction…

A D JAMESON [leaning back from his seventh helping of tiramisu]: At the risk of spoiling such a fine meal, perhaps you and I can finally figure out why we’ve butted been butting heads regarding the nature of experimental fiction.

CHRISTOPHER HIGGS: OK.

ADJ: Let’s start by each defining what we think experimental fiction is!

READ MORE >

Craft Notes / 48 Comments

February 27th, 2012 / 8:01 am

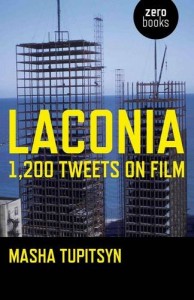

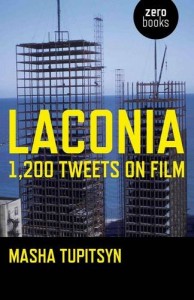

When I first read Masha Tupitsyn’s hybrid-genre book Beauty Talk and Monsters (Semiotexte), I was completely floored by it. So I was excited to read her new book LACONIA: 1,200 Tweets on Film (Zero Books)—a book of aphoristic film and media commentary written in the spirit of cultural observers like Chris Marker. There is something beautiful about Masha’s way of “reading” culture, how she honors the connections and resonances of the media she encounters, the way it is processed, assimilated and re-invented when it is filtered through her perception; intermingling with specific memories and preoccupations. Masha integrates the subjective and the critical in a way that demonstrates the specificity of our encounters with media. Both Beauty Talk and LACONIA could be described as a literary approach to film criticism, but it’s also fitting to describe the works as a cinematic approach to literary writing. In Beauty Talk, narrative and a criticism are tightly interwoven. As stories, the essays are stunning; as critical analysis, sharp. Masha’s recent book LACONIA reminds me of the ways in which the viewer is also a meaning-maker, a participant critic.

When I first read Masha Tupitsyn’s hybrid-genre book Beauty Talk and Monsters (Semiotexte), I was completely floored by it. So I was excited to read her new book LACONIA: 1,200 Tweets on Film (Zero Books)—a book of aphoristic film and media commentary written in the spirit of cultural observers like Chris Marker. There is something beautiful about Masha’s way of “reading” culture, how she honors the connections and resonances of the media she encounters, the way it is processed, assimilated and re-invented when it is filtered through her perception; intermingling with specific memories and preoccupations. Masha integrates the subjective and the critical in a way that demonstrates the specificity of our encounters with media. Both Beauty Talk and LACONIA could be described as a literary approach to film criticism, but it’s also fitting to describe the works as a cinematic approach to literary writing. In Beauty Talk, narrative and a criticism are tightly interwoven. As stories, the essays are stunning; as critical analysis, sharp. Masha’s recent book LACONIA reminds me of the ways in which the viewer is also a meaning-maker, a participant critic.

#481. IN AMERICA, WHEN YOU ATTACK THE CULTURE INDUSTRY, YOU ARE CALLED CYNICAL. BUT IT SHOULD BE THE OTHER WAY AROUND. *

“Postmodern irony means never having to say you are sorry. Or that you are serious.”

–Suzanne Moore, Looking for Trouble

Cultural studies is on the rise. The canon is dying, or at least is seriously ill. Critics are now turning their attention to the media that surrounds them—sitcoms, Hollywood films, magazines, pop music, kitsch, reality TV, fashion trends, internet memes. Repulsed by the academic elitism of cultural criticism as well as the notion that there are certain texts that are unworthy of the critic’s attention, the proponents of cultural studies have launched a vitriolic attack on the hierarchical distinction between high culture and low culture. The exclusion of “low” and popular culture and the privileging of refined culture and art that caters to a specialized/trained audience has its problems: it reinforces the idea that art is an “autonomous” institution while implicitly promoting classism, eliminating the perspective of lower class folk and ignoring subaltern cultural production and engagement (Adorno famously denounced jazz music).

READ MORE >

READ MORE >

November 10

Struck by the abstract nature of absence; yet it’s so painful, lacerating. Which allows me to understand abstraction somewhat better: it is absence and pain, the pain of absence–perhaps therefore love?

I always get an innate pleasure out of reading Roland Barthes. To be fair, I haven’t read much of his early work in which he lays out his ideas on structuralism, but I did read & briefly obsess over Writing Degree Zero. However, I think it’s the later works, where some sort of self is revealed, that I find most pleasurable. Take the ubiquitous Camera Lucida, a text that, surely, enraptures a large number of readers: Barthes centers his ideas on a photograph of his mother in her youth, the entire text, the ideas, arrive at the reader from this starting point.

There’s an intellectually rigorous, yet somehow still very casual, sense of thought present in the work of Barthes. As a thinker, especially a thinker involved with the Tel Quel group & (eventually) post-structuralism, his writing is also remarkably lucid, simple even. Where Derrida, Deleuze & Guattari, Sollers himself can accurately be described as dense in their thoughts, the words on the page, with Barthes there’s a sense of breathing. Many of his books are also often less than 120 pages.

But this is not a trick– Barthes is not post-structuralism lite, and I don’t think anybody would imply this. But I guess that’s not the point here. A friend sent me a copy of the most recent of Barthes’s work to be translated, Mourning Diary. The book is a series of notes left almost daily by Barthes on note cards after the death of his mother. Barthes was remarkably close to his mother, and the death struck a very heavy blow.

READ MORE >

11 Comments

March 10th, 2011 / 6:49 pm

From “Blind and Dumb Criticism” in Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers:

From “Blind and Dumb Criticism” in Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers:

Why do critics thus periodically claim their helplessness or their lack of understanding? It is certainly not out of modesty; no one is more at ease than one critic confessing that he understands nothing about existentialism; no one more ironic and therefore more self-assured than another admitting shamefacedly that he does not have the luck to have been initiated into the philosophy of the Extraordinary; and no one more soldier-like than a third pleading for poetic ineffability….

The reality behind this seasonally professed lack of culture is the old obscurantist myth according to which ideas are obnoxious if they are not controlled by ‘common sense’ and ‘feeling’: Knowledge is Evil, they both grew on the same tree….

In fact, any reservation about culture means a terrorist position.

True, there are revolts against bourgeois ideology. This is what one generally calls the avant-garde. But these revolts are socially limited, they remain open to salvage. First, because they come from a small section of the bourgeoisie itself, from a minority group of artists and intellectuals, without public other than the class which they contest, and who remain dependent on its money in order to express themselves. Then, these revolts always get their inspiration from a very strongly made distinction between the ethically and the politically bourgeois: what the avant-garde contests is the bourgeois in art or morals–the shop-keeper, the Philistine, as in the heyday of Romanticism; but as for political contestation, there is none.* What the avant-garde does not tolerate about the bourgeoisie is its language, not its status. This does not necessarily mean that it approves of this status; simply, it leaves it aside. Whatever the violence of the provocation, the nature it finally endorses is that of ‘derelict’ man, not alienated man; and derelict man is still Eternal Man.

*It is remarkable that the adversaries of the bourgeoisie on matters of ethics or aesthetics remain for the most part indifferent, or even attached, to its political determinations. Conversely, its political adversaries neglect to issue a basic condemnation of its representations: they often go so far as to share them. This diversity of attacks benefits the bourgeoisie, it allows it to camouflage its name. For the bourgeoisie should be understood only as synthesis of its determinations and its representations.

–Mythologies, page 139-140

Power Quote / 30 Comments

October 11th, 2009 / 4:32 pm

From “Blind and Dumb Criticism” in Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers:

From “Blind and Dumb Criticism” in Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers: