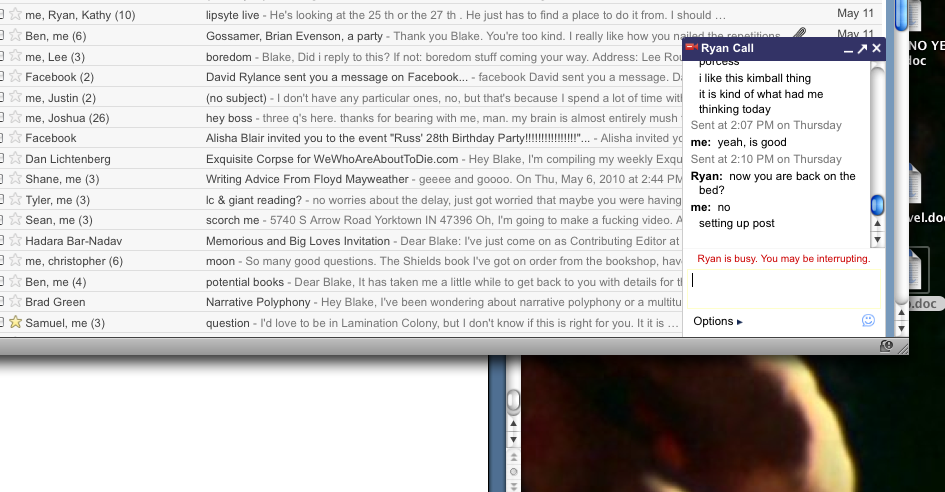

Where the Words Come From: A Gmail Fuckoff about Getting Work Done

Ryan: wat else you doing rightnow?

like this instant what ar eyou doing!

i am always curious what you doSent at 1:45 PM on Thursdayme: hahai was laying on the bedthen i got back up and saw your msgi got up cuz i thought of a sentence for this collab thing i am trying to finish a draft ofRyan: hahai seeyou just think sentences?i dont think sentencesi dunnoi cantmy braini dunnome: well i have a set of images the thing is ending withand i had a sentence that resolves one of them occuryeah i think entirely in sentences mostlybut often based out of an initial image or situation of imagesso the sentence kind of falls out of the image in specific wordsbut i dont really think about the wordsor the image

Michael Kimball Guest Lecture #5: Language and Sentences

We are writers. Writers use language. There are lots of things we can do with language. As Robert Lopez says: “I always start with language.” And when he says that, he means his language, his particular language, and that every writer should have their own particular language. Raymond Carver gets at that with this (from “On Writing”): “It’s akin to style, what I’m talking about, but it isn’t style alone. It is the writer’s particular and unmistakable signature on everything he writes. It is his world and no other. This is one of the things that distinguishes one writer from another.”

We are writers. Writers use language. There are lots of things we can do with language. As Robert Lopez says: “I always start with language.” And when he says that, he means his language, his particular language, and that every writer should have their own particular language. Raymond Carver gets at that with this (from “On Writing”): “It’s akin to style, what I’m talking about, but it isn’t style alone. It is the writer’s particular and unmistakable signature on everything he writes. It is his world and no other. This is one of the things that distinguishes one writer from another.”

When I think of language, I think of sentences. As John Banville says: “The sentence is the greatest human invention of civilization.” There are lots of things that we can do with a sentence. We can manipulate the syntax, the diction, the stresses, the tenses, the acoustics, the morphemes and the phonemes, syllables and prefixes and suffixes, the speed, and the length. As Andy Devine says: “The English sentence – because of English syntax – is infinitely expandable.”

We can manipulate objects, subjects, predicates, infinitives, participles, gerunds, phrases, clauses, and determiners. We can manipulate articles, nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, and prepositions. Joseph Young says: “Articles propel the sentence, push it off and keep it moving.” Stephen King says: “The road to hell is paved with adverbs.” Joseph Brodsky says: “Don’t use too many adjectives.” Andy Devine says: “Adjectives are not as bad as adverbs.”

For instance, I like to structure sentences around articles and conjunctions and prepositions—the more perennial parts of language—so that my narrator has a singular way to speak. And I like to move prepositions to the end of the phrase or the end of the sentence. That was one of the first sentence things that I figured out for myself. It’s not what we’re taught to do, but it is still quite obviously English, and it creates a kind of semantic link in the sentence—and this vaguely unsettling feeling.

‘Late-Night Special’: A Conversation between Dennis Cooper and Blake Butler

Dennis Cooper and I met outside of PS122–the East Village-ish space for his glorious Jerk–and stood in the cold and talked for a while. Eventually, Blake Butler and Justin Taylor showed up (he’d be listening–a conversation between him and Josh Cohen is forthcoming). We were in no little rush, since Dennis had to be back at the theater in forty-five minutes. I wanted to do the interview in a Subway. No one thought that was funny. Eventually we ended up in some ill-lit restaurant chosen on a whim. Dennis ordered a quesadilla. He eventually finished it. Dennis is a vegetarian.

Dennis Cooper and I met outside of PS122–the East Village-ish space for his glorious Jerk–and stood in the cold and talked for a while. Eventually, Blake Butler and Justin Taylor showed up (he’d be listening–a conversation between him and Josh Cohen is forthcoming). We were in no little rush, since Dennis had to be back at the theater in forty-five minutes. I wanted to do the interview in a Subway. No one thought that was funny. Eventually we ended up in some ill-lit restaurant chosen on a whim. Dennis ordered a quesadilla. He eventually finished it. Dennis is a vegetarian.

I listened. I recorded.

There was such bad music playing in there.

This is a pretty long conversation.

January 21st, 2010 / 5:22 am

Thinking about Intervals and Nature

As the new year and decade begin, I’m thinking about intervals. Most instantly, a year seems to be a more natural interval than a decade. Roughly the same things happen each year. There will be a shortest and a longest day and the air will grow warm and then cool again. The arbitrary part of a year is in its stopping/starting point. Nothing is magical so far as I can see about where we choose to end one year and begin the next. If anything, I’d prefer to wait until mid-February or so to conclude all of last year’s business and begin anew.

As the new year and decade begin, I’m thinking about intervals. Most instantly, a year seems to be a more natural interval than a decade. Roughly the same things happen each year. There will be a shortest and a longest day and the air will grow warm and then cool again. The arbitrary part of a year is in its stopping/starting point. Nothing is magical so far as I can see about where we choose to end one year and begin the next. If anything, I’d prefer to wait until mid-February or so to conclude all of last year’s business and begin anew.

A decade in the natural world seems to mean not much. But what about in a lifetime? Age 0-10, age 10-20, age 20-30, and so–these seem a bit more adequate as era-markers. Even in the 1800s decades were given sobriquets. There were the Hungry Forties (think potato famine) and the Gay Nineties (aka the Naughty Nineties; aka the Mauve Decade). But not before that; what about modernity made the decade seem like a definable, describable, identifiable interval?

Day is perhaps the truest time-interval. The sun will rise and set. While a year is a real thing, a felt thing, it is usually too drawn out and diffuse to pinpoint or summarize in a word. If you say that 2003 was a good year, I will know that it took the space of time for you to make that judgment. Mid-year, there is no telling. But a day has a character and a shape detectable even as it passes. It is defined by its largest moment. It can be remade no more than once, and the next day may be something else entirely. “Weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning” (Ps. 30:5).

These are time intervals. Modern space intervals mean very little (inch, mile, pint) and exist only for the purpose of standardization, ratio.

Then there are language intervals.