Overboard

I.

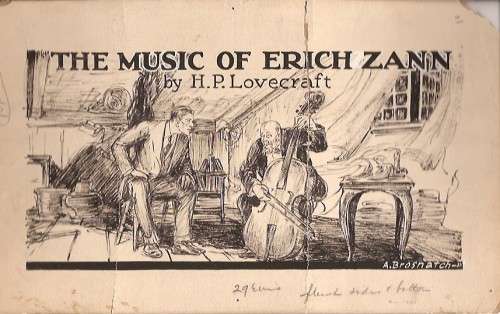

On this particular evening, the musician allows his fellow lodger in the house on Rue d’Auseil to listen to his feverish viol music. “It would be useless to describe the playing …. He was trying to make a noise; to ward something off or drown something out—what, I could not imagine,” writes H.P. Lovecraft in “The Music of Erich Zann.” The listener, a metaphysics student at an unnamed university, is an interloper, a voyeur who, on hearing Erich Zann fill his garret room with this crazed playing, hopes to peak into the source of the music’s beauty, to penetrate some “far cosmos of the imagination.” On this particular evening, the cosmos stabs back. Lovecraft describes Zann’s playing, which grows “fantastic, delirious, and hysterical …. [l]ouder and louder, wilder and wilder,” until other-worldly chaos and pandemonium explode into the house on Rue d’Auseil and the listener flees. It is a bit much.

Howard Philips Lovecraft wrote “The Music of Erich Zann” in 1917. Over the next 20 years, he would go on to write his best known tales of horror and wonder, those involving Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep, and Azathoth, his mythos monsters, the Great Old Ones whose names you can’t pronounce. The language in “Erich Zann” is toned-down, tolerable, a pale lilac compared to the rich purple of his later prose, where, as Michel Houellebecq writes, “the adjectives and adverbs pile upon one another to the point of exasperation, and he [Lovecraft] utters exclamations of pure delirium.” Most readers would not consider anything by H.P. Lovecraft well-written in the traditional sense, and yet there is power in his work, a majestic and odd darkness that isn’t matched by much else, an appeal to the unimaginable, our dread of looking into the night sky and hoping, only hoping, we’re alone. Lovecraft’s best sentences are always overwrought. There are excesses of bland fright words—“monstrous”, “horrible”, “grotesque”—mixed with archaic vocabulary, weird words that both in texture and meaning evoke the unusual, “eldritch”, “rugose”, “squamose”; there are extended hallucinations, delirious exclamations, and dream descriptions of nightmare cities, all of which are the antithesis of subtlety. All stylistic restraint has been set aside. Lovecraft eschews any kind of linguistic modesty so he can unleash his unmistakably curious vision of cosmic horror and god-things—this is the source of his style.

“HPL would probably have considered a story a failure, if in writing it he did not have a chance to go overboard once at least,” Houellebecq writes in H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life (published in France in 1991; translated into English by Dorna Khazeni and published by Believer Books in 2005). Houellebecq, a French novelist who writes about sex, brand names, technodystopian malaise, and ennui-ridden postmodern consciousness (very French, yes), sees Lovecraft as an American original whose uncompromising weirdness and “stylistic explosion[s]” lead to a unique body of work, the sole goal of which is to fascinate the reader. Houellebecq sets Lovecraft up against more mundane sci-fi and horror writers and against all realism. Lovecraft, Houellebecq argues, whose style is defined by precisely that which it’s easiest to criticize, is interesting not in spite of his grandiose and ridiculous prose, but because of it.

The Books I Want to Read During the Summer

Much like Mary Tudor and Anne Boleyn, summer and I are the antithesis of amicable. I hate heat. I heat sweat. I hate seeing human skin. I hate swimming. I hate sunlight. All of these tasteless traits are allotted a starring role in June, July, and August. Already, I want winter to come. The cold, the frost, snow, booties, mittens! Winter is sort of more elaborate than summer. While I never want to be a part of this world, (and by this world, I mean you-know-whos with you-know-what values), I really don’t want to be a part of this world in the summer. Since Mary refused to recognize Anne as England’s queen, I’ll refuse to recognize summer. Instead, I’ll read books (one, obviously, should always read books, since it’s one of the utmost Christian activities), including:

FunSize&BiteSize by Ji Yoon Lee: She resembles a cute tiny kitty who everyone wants to pet, only no one actually does, since nearly everyone is aware that if you attempt to do such a thing then she’ll bite you, and while that bite may not hurt much at first, eventually it’ll turn into a disease much more fatal than the kind gay people get. A preview: “Fetishize my misery / Not white American male’s.”

I Will Never Be Beautiful Enough to Make Us Beautiful Together by Mira Gonzalez: She seems sad, depressed, moody, discontent, and all the other things that most anyone with any perceptiveness would be right now. She also has a rather captivating name. “Mira” is light and delicate, like a fine piece of fabric. “Gonzalez” is also the last name of the former Texas Ranger baseball player Juan Gonzalez. This All Star constantly hit home runs, which are quite dramatic. Preview: “i feel like 400 dead jellyfish in the middle of a freeway.”

Lemonworld & Other Poems by Carina Finn: She’s basically a modern princess (one of the poems in this book is titled “modern princess”) who has come home for winter break to visit her mommy and sigh flippantly and eloquently at the whole entire universe. Carina likes yummy food (browniemix), fashion accessories, like ribbons, violence (“peace is a field of graves”), and the types of things Gertrude Stein would like — “16-year-old girl looking to buy a moustache.” To spotlight her forceful mercuriality, Carina includes plentiful exclamation points, one of the most comely types of punctuation marks ever. A couplet: “don’t trump the mode / there’s a rabbit in the marshmallow!”

Pageant Rhymes by JonBenét Ramsey: Last summer, the cute Tumblr literary corporation Bambi Muse published Baby Adolf’s Nursery Rhymes to much acclaim. Even presumed adversities (presumed, due to a certain trait) were laudatory. “Nothing to complain ’bout here,” was Saul Bellow’s hearty response. This summer, Bambi Muse will publish a collection of couplets by the sensational JonBenét. The verse touches on yummy victuals, fashion, and other things. A couplet: “Cheddar broccoli soup is most profound. / I was killed in my pink Barbie nightgown.”

Taipei by Tao Lin: This boy, though a straight boy, seems like a manipulative psychopath, so I’m invariably curious about his compositions.

TwERk by Latasha N. Nevada Diggs: A little bit ago, Joyelle McSweeney posted about these poems. From what I’ve read, they contain the qualities of a circus as well as a loud, unmitigated drag ball. Even the author’s name teems with theatrics. Nevada is home to quite a few cinematic creations, like Casino (a mafia movie) and Liberace (a boy first and now a movie starring Michael Douglas and Matt Damon).

The Diary of Anne Frank by Anne Frank: I’ve read this book bountifully, obviously, and I will continue to do so during the summer months (and I’m not talking about the Sex and the City version either!) Caitlin Flanagan says Anne is an “imp, a brat, a narcissist, a sulker, a manipulator, a manic talker, a flirt, and a person who insisted on the rapt attention of everyone around her at one moment, and on the pure privacy that all misunderstood people demand at the next. ”

Petocha/Chiflada by Monica McClure: The sharply chic Mona is publishing a bratty chapbook with wtfislongsdrugspress, a new press founded by Carina and Stephanie Berger, the princess of The Poetry Festival. It’s invariably estimable when tiny, pretty girls work together on a particular project, it’s kind of like an episode of The Babysitters Club.

The Bible: A ton of people are on a path to hell, but by perusing this text (not just for summer, either) they just may be able to take the trail to heaven, where Edie Sedgwick and Edith Sitwell convene tea parties.

Dressing Up Maggie Nelson

I first became of aware of Maggie Nelson when I overheard two feminist girls debating whether or not what “she was doing” was ethical. I did not know what “she was doing,” nor did I care. I was forbidden to read her. She was a girl, and for quite a bit it was against the law for me to read girl poets besides, of course, Sylvia. The ban against girls began when a teacher (another feminist, and certainly not the catty, commendable kind) assigned us the Sharon Olds’s poem “The Language of the Brag.” The poem perpetuates the base boast: “I have done what you wanted to do, Walt Whitman, / Allen Ginsberg, I have done this thing.” Oh bother! A demographic whose primary goal is to be like two hairy free-verse guzzling perverts will elicit neither esteem nor heed from me. But then another teacher (a boy one) suggested I read Ariana Reines. Ariana isn’t an intolerably gregarious gay and she isn’t a beatnik-hippie sodomite. Ariana is a monster. In one poem in The Cow, she munches her own poop, sips her throw up, and goes down on herself. She is “self-contained”: disciplined and exacting. She is a sword-sharp: the antithesis of the free verse commoners who are as loose and watery as Barack H. Obama’s negotiating skills.

I first became of aware of Maggie Nelson when I overheard two feminist girls debating whether or not what “she was doing” was ethical. I did not know what “she was doing,” nor did I care. I was forbidden to read her. She was a girl, and for quite a bit it was against the law for me to read girl poets besides, of course, Sylvia. The ban against girls began when a teacher (another feminist, and certainly not the catty, commendable kind) assigned us the Sharon Olds’s poem “The Language of the Brag.” The poem perpetuates the base boast: “I have done what you wanted to do, Walt Whitman, / Allen Ginsberg, I have done this thing.” Oh bother! A demographic whose primary goal is to be like two hairy free-verse guzzling perverts will elicit neither esteem nor heed from me. But then another teacher (a boy one) suggested I read Ariana Reines. Ariana isn’t an intolerably gregarious gay and she isn’t a beatnik-hippie sodomite. Ariana is a monster. In one poem in The Cow, she munches her own poop, sips her throw up, and goes down on herself. She is “self-contained”: disciplined and exacting. She is a sword-sharp: the antithesis of the free verse commoners who are as loose and watery as Barack H. Obama’s negotiating skills.

Obviously after I discovered Ariana and the rest of Rebecca Wolff’s spitfire songstresses my ban against girl poets had to be banned. This meant I could finally read Maggie, which turned out to be marvelous. Maggie is obsessed with ghastliness, terror, and the dead. She devotes “years of compulsion, confusion, and damage” writing about her Aunt Jane, a girl who was viciously murdered while returning home from college. Moreover, she’s compelled by one of the most blessed, articulate, and mischievous girls to ever be forced to live on earth… Anne Frank! “But who can guess / what Anne would have said / about the last place she went,” Maggie tantalizes. Indeed, Maggie has outstanding tastes and curiosities, so I will provide her with three outfits so that she feels fabulous in her wonderfully horrific world.

The Romantic or The Playful: a conversation about art and happiness

In response to this excellent post, Sean Lovelace said this:

I detest the write-or-I will-die-school.

Why can’t people write an intellectually stimulating activity, as intellectual play?

It has to always be ink-as-blood thing?

I don’t get it.

I’m going to suture in my (slightly edited) response here, as well. I would love input from all.

Styles

Do you fear style in poetry?

Do you skeptic it?

Once the style is figured out, does it become less impactful?

My favorite writers are styled.

Their words have good hair.

Lack of style seems to be what keeps good words from becoming distinguished words.

I still look for things that I think are “cool”

“Cool” I think appeals to the mind more than the heart.

It doesn’t need to be overt.

“Cool” is the neon sign that comes to mind when reading Cows by Frederic Boyer just published in the new Puerto Del Sol

V.

The cows are useful and sure. Their existence is an infinite number of successive

presents.

It is thus understandable with what pleasure we exterminated them.

The cows are only themselves when gathering into their own finitude the infinite

totality in which they found themselves. Beneath a tree. In a meadow. On the earth

lost in the universe.

The human being is quickly jealous of the cows. Oh, if only the gods would arm

me with such power—comes the muffled voice of tiny Telemachus that is held in The

Odyssey.

The cows don’t read what’s in our hearts. They don’t understand us any better

than we understand ourselves. They ask neither for our recognition nor our gratitude

nor our hate as we ask it of ourselves. And never have we contemplated them in their

truth.

Thought, the cows immediately knew in our presence, betrays general indifference.

It’s only when dangers become evident that indifference ends. In our presence

the cows learned this at their own expense.