Death Centos by Diana Arterian

Death Centos

Death Centos

by Diana Arterian

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2013

24 pages / UDP Page

When my 12 year old daughter rolls her eyes at me, I tell her stop it. I say, stop it. You shouldn’t treat me like that. I’m going to die someday.

She says, Mom, I know.

My husband says, Both of you, stop it.

But I can’t. I can’t stop. So I tell her, we’ll be dead forever. Just think about that: forever. Infinity. All of time. And we are only alive for a little second of it, and we barely even get to know each other, and you want to waste the little time we do have being alive rolling your eyes at me.

My husband says, Please, Sara. Not this shit again. Don’t say that.

Jeez, Mom. Seriously. I know we’re going to die.

But you don’t get that it is really soon. I could die tomorrow. So could you.

My husband says, Stop. No more. Stop saying that shit tonight. Just not tonight. Let’s just watch a show together, and enjoy our evening. Please, he implores, not tonight. No death stuff tonight.

The book of poems, Death Centos, by Diana Arterian is a book of poetry made by collage and with constraint. Arterian has created a mixed tape of famous figures’ final words. Her poems pull the final phrases of famous persons from their resting places of mythology and arranges these phrases into poems. Death Centos, conceptual in conceit or not, is a book of poems that is rich and profound. The author doesn’t seem as displaced as in most pieces of conceptual writing. This contributes to a feeling of stability within the text. The poems are full of hearty material. The words are the actual final words of folks before death. Most of the folks quoted carry some importance in the trajectory of civilization. These words lend to the power of the poems, but that isn’t the whole story. The arrangement of the words is of paramount importance. I am not a poet. And because of this I can consume poetry in a way that allows my mind to form ideas from the poem, or access to the subtext in a way that feels more mystical than an outright technical analysis would. I’m talking about feelings here. I feel that the work is good. I feel the poems are strong. I felt stirred by them, and provoked. I take this to mean that art is working.

In the first poem “I” in the section LAST WORDS OF THE DYING there is a list at the side of the page highlighting the people whose words have been arranged in the poem: Ludwig van Beethoven, Frederic Chopin, Thomas Edison, Franz Ferdinand, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Victor Hugo, Timothy Leary, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Theodore Roosevelt, Tom Simpson, Rudolph Valentino. There are only ten stanzas in the poem and the punctuation defies orderliness. There are no clues here, just a list of contributors. From the first I realized there would be no real correlation between the order of the contributors, and the poems’ inclusion— or, if there was, it would be more work than any book of poetry should be. I found myself wanting the poem to align with list of personas so that I could figure out who said what at the end of his life, but Arterian wasn’t going to let that happen.

Perhaps this description of my experience with this conceptual piece of work seems pedestrian to you. I think though, that my experience is worth talking about. For so long I felt shut out of conceptual work. That is a huge part of the culture to miss out on. Conceptual projects and poems intimidate cultural consumers. MFA programs like the one I went to are rife with what could be either interesting experiments or half-hearted attempts at grabbing some attention. You have to get close to tell the difference. Only now, years after school, do I find myself brave enough to get close, to engage, and to speak about the work. However, by no means am I an expert. I am a dilettante.

Arterian’s first poem taught me how to read the rest. It taught me what to do from the first. I think this says something about the accessibility of her work. About the potential appeal. Not everyone is going to care about poetry, but everyone should feel welcome to engage. I think that the content of Death Centos is inviting. Macabre, yes, but death is coming. To each of us. And “this is the fight of day/and night.” This is a space of common ground. This is a book of inclusiveness. This is a book of successful appropriation where the original text adds up to so much more than any of the snippets.

Each of the poems begs to re-read. There is a smoothness despite the punctuation. The poems flow and drip. Arterian is a master at moving you down through poem at a steady pace. In the poem “V” in the first section of LAST WORDS OF THE DYING three names are listed down the side: Warren G. Harding, Frida Kahlo, Martin Luther King Jr. I read the poem “V” three times in each voice, letting each one of these famous persons own the words of the others in a vision of their respective deaths.

Make sure you play “Precious Lord”

tonight—play itreal pretty. That’s good.

I hope the exit is joyfuland I hope to never

July 4th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Inclusion in Ed Steck’s The Garden

The Garden

The Garden

by Ed Steck

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2013

104 pages / $14 Buy from UDP

If the Romantic model of the garden is cultivation, then the Post-War model is invasion. Robert Duncan inquires of that famous, primordial garden, “is it dream or memory? homeland of the pleasure principle in the libidinal sea, an island girt round with forbidding walls?”[1] And of ornamentation, William Carlos Williams reminds us “that the bomb also is a flower.”[2] The multiflorous gardens of Ronald Johnson abstract whole histories for admission into their horticultural field. Rampancy, tended by besieged consciousnesses, overruns “the old garden-ground of boyish days.”[3]

The degradation of idealized forms is, of course, a hallmark of post-modernism, but the temptation of placing the world within the garden, or enlarging one’s garden infinitely, enacts a dialogue of control and ownership that becomes problematic for any anti-imperialistic project. Similarly, there is the risk of oversimplification that an artist runs when attempting to account for the volume of media produced around the event of war. Ed Steck’s The Garden: Synthetic Environment for Analysis and Simulation, published by Ugly Duckling Presse, continues the erosion of privileged space begun midcentury with an all-important newness equipped to navigate the bizarre landscape of the 21st.

June 23rd, 2014 / 10:00 am

Imperial Nostalgias by Joshua Edwards

Imperial Nostalgias

Imperial Nostalgias

by Joshua Edwards

Ugly Duckling Presse, April 2013

96 pages / $15 Buy from UDP or SPD

Joshua Edwards begins Imperial Nostalgias with two short parables. One tells the story of a Traveler, another of an Outsider. The poems are immediately evocative and irresistible in the tradition of Italo Calvino and his Invisible Cities, or more recently Srikanth Reddy’s take on Dante. From there, Edwards wades into cinematic territory in a series of photos. These describe a journey through a “Valley of Unease.” We see ruins, a stray dog, and a bonfire at night.

The third section, a prose poem called “Departures,” is the strongest in the collection. The travelogue model works as a compelling framework to satirize and embrace American anxieties in “slightly foreign” lands. The poet approaches Imperial Nostalgias with clear eyes. In an interview earlier this year with the Studio One Reading Series he admitted, “Imperialism is in the cereal I eat and the culture I consume, and the ghost of Manifest Destiny looms large in the histories of the states I’ve spent most of my life in.” Like Ben Lerner’s terrific Leaving the Atocha Station, the work engages the aesthetics and the ambivalence of young Americans abroad.

Edwards works through anxieties, but he still perpetuates the myth that there is such a place as “abroad.” So while there is little talk of the cringey Tinker, Tailor, “These boys were born to empire,” type nostalgia in the collection, there is still a very clearly articulated imperialist nostalgia. This comes out in snatches,

I wake up and then drink tea, then relax

On my friends couch to watch Paris, Texas

For the first time. When someone goes silent,

Or when a siblings room is filled with sorrow,

The whole world resembles a motel room.

Edwards chooses a very particular aesthetic (He evokes French minimalists like Toussaint, art galleries, (Like Lerner, Imperial Nostalgias repeatedly returns to art museums as if too say this too is a high concept endeavor), washed out desert scenes, vague Orientalism, Paris, Texas, etc) that effectively conveys a certain moment in American (therefore world) history: 80’s independent film and Conceptual Art.

In the translation of this aesthetic, Edwards shows a drive towards the mysterious and apophatic. When Bell Hooks wrote about Imperialist Nostalgia, she focused on celebrities like Madonna, performing blackness. She employed the now well-worn “eating the Other” type analysis. But really, it’s important to remember there’s a lot of Other there (too much to eat), and in terms of nostalgia this comes out in the apophatic or the unknowable. For 80’s Conceptual Art or even Paris, Texas, the mystery deepens as it ages. And difficult to decipher social orders become conflated with truly the truly unknowable. The work of Cindy Sherman, or Vancouver School Photographers, lately much celebrated and mimicked, have taken on a sheen of romance. And this says something about conceptual photography in the 80’s and a whole lot more about the way we live now. It’s common for artists to romanticize and re-imagine the past, but this has everything to do the artist’s personal contemporary.

For artists of a certain generation Paris, Texas becomes a type of nostalgic touchstone; it represents not a time before there was American empire, but perhaps before the artist knew about American empire. The unknown swirling around Harry Dean Stanton would be a lot less unknown for an older generation of filmgoers that had seen him act in movies beginning in the 1950’s. In a recent HMTLGIANT post, Felix Bernstein imagines art “that may or may not know (symbolic order) networks exist.” Paris, Texas is a beautiful film, certainly nostalgic for great Cowboy and Noir films of an earlier era, but the complex social networks it explores (poverty in the panhandle, cold war malaise) might be different for an older artist living in Houston, for example. Recognizing the precarious position of a would be counter-cultural American artist abroad, Edwards compulsively recreates an aesthetic of the Imaginary or in-between, when the startling symbolic order networks do not exist for him, but not an aesthetic from when they did not exist. And by translating this aesthetic again and again, Edwards is free to play Cowboys and Indians.

***

Joseph Houlihan lives and works in Minneapolis, MN.

November 4th, 2013 / 11:00 am

25 Points on Ideisms: Beginnings Toward the Poetics of Always After

Being a Review of Notes

on Conceptualisms

by Robert Fitterman and Vanessa Place

Notes on Conceptualisms

by Robert Fitterman and Vanessa Place

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009

80 pages / $10 buy from UDP

As it is high time that our growing faction of Ideists had a manifesto around which they could unite, we, that is, Joel Kopplin and Kurt Milberger, humbly offer these notes toward a report of the history and conceptions of Ideisms with particular emphasis on the practice’s aesthetics, specifically poems.

1) The poetry of Ideism: the hangnail that breeds, that bleeds when finally plucked.

2) Books are bound to remain unread because to really read is a kind of rape.

3) Ideism thinks through houses, beyond their walls and windows, and out into the atmosphere where it burns as falling space junk.

4) Ideism is the eternal window out, the rhombus artfully set before venetian blinds, condensed so as to see the street below to approach the equation: what, finally, is next?

5) The permutations of the phrase reveal the poetics of Ideism. Id-e-ism. I-deism. Id-eism. The symbol multivocates, illuminates, and refuses to condense its referent.

6) Ideist poetry reconstructs new acronyms which compress and describe discourse-specific speak: philistines and neophytes fall down and weep with shame upon the altar of each letter of the new word. READ MORE >

July 2nd, 2013 / 1:08 pm

It’s No Good

Kirill Medvedev was born in Moscow in 1975. In addition to writing, he has translated, written critical essays on contemporary Russian literature and politics and their “bloody crossroads”, run his own bare bone publishing house, and organized opposition against Putin.

His first book of poems, Vse Plokho (Everything’s Bad or It’s No Good) appeared in 2000; his second book Vtorzhenie (Incursion) combined poetry and essays on subjects ranging from 9/11 to the vocabulary of pornography. Soon, thereafter, fed up with Moscow’s intellectuals acquiescence with Putin’s stabilization (or, as he might say, pacification), he went into “internal exile”—renouncing all contacts with literary life, whether publishing, readings, or roundtables or even claiming copyright for his writings. While continuing to post his poems and essays on his website and Facebook page, he has channeled his considerable energy into publishing (mainly canonical leftist criticisms of capitalism, well known in the West but not in Russia), political activity as part of the small socialist movement Forwards (Vpered) and taking to the streets to challenge Putin’s regime together with a few supporters holding handmade signs.

In It’s No Good, Keith Gessen brings together a representative sample of Medvedev’s diverse ouvre. Selections of poems from his two collections and later works as well as of his essays are preceded by Gessen’s extensive introduction to Medvedev, the poet and, equally importantly, Medvedev the critic of literature, the literary establishment, and Russia’s stunted politics. We learn how Gessen discovered Medvedev’s poetry and political writing and how it downed on him that Medvedev had very important things to say to him and to his New York friends who were trying to confront the inequities of capitalism in their own backyard. The collection, an obvious labor of love, works effectively at many levels and will surely widen the circle of Medvedev’s admirers in this country. Would it be wishful thinking that it will also, as if by ricochet, do it for Medvedev in Russia?

January 18th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

It Takes Two, Baby

long past the presence of common

long past the presence of common

by j/j hastain

Say It With Stones, 2011

87 pages / $12 Buy from Say It With Stones

&

Dear Failures

by Trey Sager

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2011

28 pages / $10 Buy from UDP

This week I went to an art museum showing contemporary work by two gay male artists. The two exhibits were chosen to put the pair in conversation with each other: Donald Moffett, who worked with Act-Up in the eighties, and Glen Fogel, who was born in 1977. I wandered through the exhibits looking at the projected paintings, arms emerging from holes, wedding rings and re-painted love/hate letters. Afterwars, I walked outside into the cool autumn air and sat down in the sculpture garden next to the museum. I’d been trying to make time to read j/j hastain’s new book long past the presence of common, and I finally had made the perfect moment. The sun was setting through the trees, the air was warm enough.

October 28th, 2011 / 12:00 pm

Thinking Around gowanus atropolis by Julian Brolaski

gowanus atropolis

gowanus atropolis

by Julian Brolaski

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2011

104 pages / $15.00 Buy from UDP

We no longer reveal totality within ourselves by lightning flashes. We approach it through the accumulation of sediments.

– Edouard Glissant

Every word in gowanus atropolis carries the traces of having been moved, altered, shifted. Even the undergirding of the lines and stanzas feels rearranged and restructured to create a different kind of progression, far from a logical exposition. Both syntax and spelling have been remade: “one ynvents a grammatical order / (& haf done).” We are in a specific post-industrial space, the New York City around the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, and we are listening to an elegy for the pastoral in a stridently non-pastoral setting, a polluted landscape struggling to survive. The experience of this landscape through words is only possible, Julian Brolaski seems to be saying, once everything has been pushed off its foundations a bit, with everything askance, a little slanted by the inclusion of a slew of portmanteaus, archaic words, macaronics, neologisms, transpronouns like xe, and of-the-moment slang. Suddenly even the most obvious and brutal contemporary slang seems bizarre and highlighted in the mass of new or n-used words. In the thicket of all these strange words, there are some we recognize, some which very few readers could ever possibly know and then others that no one has ever read on the page before. These (queer) words open up all sorts of possible readings, mis-readings and failed readings, and they also open up a space for play, for contradiction and confusion, for being lost.

August 5th, 2011 / 12:00 pm

Another Something Happening for You City Folk

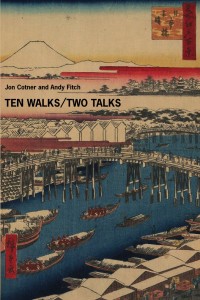

I know there’s never anything going on in NYC, but tomorrow night it looks like there’s an exception. Certainly it’s something I would attend if I wasn’t four hours away: the release party for Jon Cotner and Andy Fitch’s book, 10 Walks/2 Talks, now published by Ugly Duckling Presse.

I know there’s never anything going on in NYC, but tomorrow night it looks like there’s an exception. Certainly it’s something I would attend if I wasn’t four hours away: the release party for Jon Cotner and Andy Fitch’s book, 10 Walks/2 Talks, now published by Ugly Duckling Presse.

At McNally Jackson Booksellers in Soho — 52 Prince St

7pm

Here is the Time Out NY write-up.

This book looks to be fantastic. Definitely a great cover of 2009 (my post on this is forthcoming, late). The concept for the writing is that Jon and Andy walked around Manhattan and talked about stuff. I had the privilege of running one of their talks in Everyday Genius (read it).

They seem like pretty cool guys.