Bookmaking: !@#$%^&*

[In this series I will think aloud about the multifarious process of publishing a first book.]

The first time I ever cursed was in the fourth grade. I’d just transferred out of Catholic school to public school. I was standing at the door to Mrs. Rogers’ portable classroom, friendless and waiting to be dismissed, when I mouthed the word “shit.” Then I whispered it. Then I said it. Just like that. Shit! I couldn’t stop smiling.

I didn’t feel the same exuberant freedom again until I was 18 and shaved my head. I remember looking into the rearview mirror of my ’86 Le Sabre after I’d buzzed my hair off; I couldn’t stop grinning.

I’m 33, and it just happened for the third time. For weeks I’d been awaiting the publication of my first book, but I’d become petrified of its first poem—that it IS the first poem in the book with its one goddamn, one fucker, and one motherfucker in 20 lines, and that certain people (such as my Italian Catholic grandmother) would read that first poem and get their feathers ruffled, feel disappointed that I’m actually such a no-good heathen. What were my publishers thinking?

This poem will always be the first poem of the book. It’ll always set a tone, which is why it’s the first poem. It’ll be there to remind me that I like to run my mouth (but also to remind me that I enjoy mis-hearings, misunderstandings, and even occasional misanthropy). That’s a lot of pressure for one little guy in a sea of bigger fish (it’s close to the shortest poem in the book).

Then I got my author copies in the mail, and I realized that the language I very deliberately chose for this poem—and every poem—simply embodies my fourth-grade epiphany or my freshman-year hair buzz, those times I used my body as the subject of my own story, pleasuring in the language of the forbidden, simultaneously defining and deferring definitions (the eternal tension of différance), and felt the freedom therein.

Basically, I’m saying that if I ever go to hell, I hope it’s because of my motherfucking mouth. That’s not all I’m saying, but it’s a start.

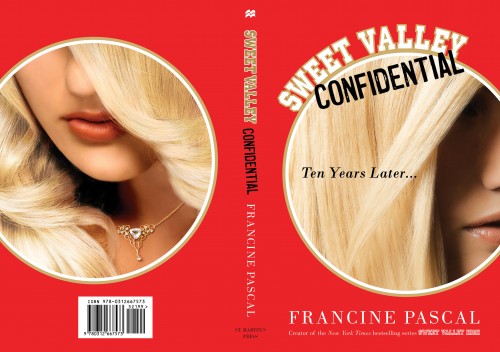

Oh, Sweet Valley Confidential!

I have an intense attachment to the books I loved as a child and teenager. I think we all do. As you might imagine, when I learned there would be a new addition go the Sweet Valley High canon, I clutched my pearls and lost my shit. I started reading Sweet Valley Confidential when it downloaded to my Kindle at 2:30 in the morning on the day it was released. Ten years have passed since we last encountered our heroines, Elizabeth and Jessica Wakefield. Everything has changed and yet, truly, nothing has changed in Sweet Valley, California. Almost every woman I know who is my age or thereabouts is reading this book right now and it has little to do with the book itself (terribly, terribly written) or the plot (horribly contrived and outlandish). It’s about remembering how much we loved the original series, and following the lives of The Twins, who were perfect, All-American girls we either loved or loved to hate. I have every reason in the world to hate everything about these books but I don’t. I love them, unabashedly and I will admit that I love this reboot, too. The drama! The scandal! Knowing where they are now!

In the original series, nearly every book began with a breathless description of The Twins and their blonde perfection. It did my heart good to see that SVC has not strayed too far from the path:

Like the twins of that poem, Elizabeth and Jessica Wakefield appeared interchangeable, if you considered only their faces.

And what faces they were.

Gorgeous. Absolutely amazing. The kind you couldn’t stop looking at. Their eyes were shades of aqua that danced in the light like shards of precious stones, oval and fringed with thick, light brown lashes long enough to cast a shadow on their cheeks. Their silky blond hair, the cascading kind, fell just below their shoulders. And to complete the perfection, their rosy lips looked as if they were penciled on. There wasn’t a thing wrong with their figures, either. It was as if billions of possibilities all fell together perfectly.

Twice.

Who else is reading this? Fess up!

my face is a gavel

Is there a correlation between someone’s personality and their literary output? Do you ever find yourself anticipating/hypothesizing/predicting/assuming what someone’s work will be like based on their intelligence/sense-of-humor/self-awareness/”‘moral’ character”/etc.? If someone is annoying in real life do you assume that their work will come at you in a 14 pt., bold, helvetica-like font and be annoying as well? And then, after you assume that, how often do you find that to be the case? If you are well liked, will your work be well liked? For those of us TOTALLY CONSUMED BY POETRY AND LITERATURE, is not our work the truest representation of ourselves? I want stories. Please share.

“Sweet Potatoes” etc

My desk is messy but on Wednesday Joe and I did a lot of work around HQ. We took down the old artish and put up some new pictures and my favorite thing was finally figuring out a way to display my chapbooks in a rack. I kept putting in chapbooks that I had in boxes and getting excited and showing them to Joe. Like, JOE! LOOK AT THIS TITLE “FALLING STARS TO SMASH MOTHERFUCKERS IN THEIR FACE”! AH HAHA AND LOOK AT THIS ONE! “CONGRATULATIONS! THERE’S NO LAST PLACE IF EVERYONE IS DEAD” – okay so maybe those titles are kind of pessimistic but there are a lot of other ones that I liked. I kept also being like JOE! THERE’S A LOT OF CHAPBOOKS IN HERE A PERSON WOULD ACTUALLY WANT TO READ!

Life is moving too fast. I can’t keep up with things like the Internet. HTMLGiant is fast like the wind — beyond me. I don’t know what’s going on anywhere. I don’t like the feeling. I feel like I’m withdrawing into my own small world of rush. I can’t talk crap about people anymore because I don’t know what anyone is doing. READ MORE >

Power Quote: Hélène Cixous

This is how I would define a feminine textual body: as a female libidinal economy, a regime, energies, a system of spending not necessarily carved out by culture. A feminine textual body is recognized by the fact that it is always endless, without ending: there’s no closure, it doesn’t stop, and it’s this that very often makes the feminine text difficult to read. For we’ve learned to read books that basically pose the word “end.” But this one doesn’t finish, a feminine text goes on and on and at a certain moment the volume comes to an end but the writing continues and for the reader this means being thrust into the voice. These are texts that work on the beginning but not on the origin. The origin is a masculine myth: I always want to know where I come from. The question “Where do children come from?” is basically a masculine, much more than feminine, question. The quest for origins, illustrated by Oedipus, doesn’t haunt a feminine unconscious. Rather it’s the beginning, or beginnings, the manner of beginning, not promptly with the phallus in order to close with the phallus, but starting on all sides at once, that makes a feminine writing. A feminine text starts on all sides at once starts twenty times, thirty times, over.

–from “Castration or Decapitation?” trans. by Annette Kiihn, included in French Feminism Reader (pg. 287)

Book Klub [w/ Sam Pink, Noah Cicero, & Jordan Castro]

3 dudes and some ladies talking to each other about wild ass books, you know?

Literature as a Two-Way Conversation

After we posted about reading Alexander Chee’s blog Koreanish as though it were a book whose ending hasn’t yet been written, Chee tried to read Koreanish as though it were a book whose ending hasn’t yet been written, and he was surprised that what he found was different from what he thought he would find. An excerpt:

After we posted about reading Alexander Chee’s blog Koreanish as though it were a book whose ending hasn’t yet been written, Chee tried to read Koreanish as though it were a book whose ending hasn’t yet been written, and he was surprised that what he found was different from what he thought he would find. An excerpt:

“What struck me, in other words, is that Koreanish the blog, is, if read narratively, something of a dystopic novel, in which a writer is living inside a country that is blind to its own destruction, a destruction it pursues relentlessly, to his increasing dismay.” (Read the rest at Koreanish.)

It’s a strange feeling to read a blog as a book whose ending hasn’t yet been written, then to have your note about reading the blog as a book whose ending hasn’t yet been written become part of the fabric of the book the blog has become, and in so doing to influence the future trajectory of the blog-as-book, which means the ending of the book you’re reading and about whose ending you are curious has now been influenced by you the reader as you act upon the writer by responding to what he has already written but has not yet finished.

If this seems newfangled and Back to the Future-ish (I briefly worried about the possibility of erasing my own existence, but, fortunately, time is only moving in one direction, for now), maybe it’s not. It seems likely to me that writers who serialized their novels in magazines or newspapers before they appeared in book forms (Dickens, for example, or Dostoevsky), and their readers, might well have been candidates for similar experiences. Ditto writers whose books appear in successive volumes over time, before they are complete — Cervantes, Proust, more recently Murakami. Or writers of trilogies or quartets — Updike, or Justin Cronin’s, which is one volume in progress.

This would be a useful subject for inquiry, I’d think — how does the reception of an in-progress book by its readership impact the future trajectory of that work. And then, of course, we’re soon thinking about the entire arc of a writer’s career, where these matters likely influence future work more often than we purists might imagine. Almost all the time, would be my guess, even if your name is Thomas Pynchon or Cormac McCarthy. Even Salinger’s great long silence seems a function of his response to the audience’s response to his work.

Maybe literature is more of a two-way conversation than we would prefer to imagine.

The Terrible Satisfactions of Fan Fiction (and Writing Who We Know As Fan Fiction)

In the late 90s, I was obsessed with a television show on USA Network, La Femme Nikita,* which was vaguely based on the wonderful French movie La Femme Nikita and the horrible remake Point of No Return. The show centered around Nikita, a woman who was forced into being a government agent for a nefarious covert agency who often had to consider the greater good while doing bad things. There were all kinds of supporting characters like Michael, her love interest and the main who trained Nikita as an agent, Birkoff, the computer genius who helped run the covert operations from headquarters, Operations, the dastardly man in charge of Section (the covert agency), and Madeline, Operations’s sometimes lover and the second in command at Section, and also worked with Nikita who was the tormented emotional core of the show. The show was filled with angsty goodness in each episode as Nikita struggled with the life she was forced into, having to kill or be killed. She had freedom, but only so much. She had Michael, but only so much. It was romantic and agonizing and wonderful. Sometimes, I wanted more than what I could get from a one hour episode. That’s how I learned about fan fiction, where fans of the show wrote elaborate stories using the characters and the world built within the show as a starting point for telling new stories. There were hundreds and hundreds of stories that asked and answered the question, “What if?” posed in countless different ways. I could read stories about Nikita marrying Michael and having a child and negotiating their careers as spies, or Birkoff and Operations having an affair (SLASH), or Nikita and Operations having an affair, or Nikita escaping and starting over only to be caught, or Madeline taking over Section or Nikita going rogue. The permutations were endless and there was something terribly satisfying about seeing just what was possible within the Nikita universe when the characters were freed from their creators.

Cool article on Mark Hogancamp in today’s NY Times. Hogancamp was the subject of the documentary Marwencol, which I posted about when I saw it a few months back. I can’t encourage you strongly enough to see this documentary, it’s one of the best films I’ve ever seen about the process of and the reasons for making art.