The Best Version of Whoever That Is: A Teaching Philosophy

Ed: Over the coming weeks (and maybe months given the number of posts I’ve received), I’ll be featuring conversations about the teaching of creative writing from teachers, both new and experienced, as well as students, all of whom are trying to answer the question, “How the hell do we teach creative writing?” Our first post comes from Laura van den Berg, author of What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us. –RG

—

For a handful of years I have been teaching creative writing in a variety of settings, mostly academic. I entered into the whole enterprise feeling a touch uneasy about claiming to be able to teach that maybe can’t be taught. My biggest worry was oversimplifying. I knew my students would need to learn the craft fundamentals of fiction, but how could I convey them in a way that does justice to the form that I love, the form that thrills and confounds me on a daily basis? Fast forward a few years and I have some ideas. I always tell my students there are no rules in fiction, only principles. Here are some of my teaching principles:

1. One of the basic problems in introductory-level workshops is that students are grappling with how to talk about what they and their peers put on the page. At the same time students want to come to class with something to say, preferably something smart-sounding (and often they succeed; I am regularly knocked-out by how insightful my students are). This can result in an unhealthy attachment to surface level issues, such as the dreaded questions of plausibility—i.e. “Was it really plausible for Aunt Ida to walk 10 miles in a hurricane? Shouldn’t it have been more like 5?” Unfortunately these questions have little relevance to the larger enterprise of the story. Of course Aunt Ida could have walked 10 miles in a hurricane and if for some reason she could not, that issue can be addressed with a margin note and a click of the keyboard. What the student probably means to say is something like: I don’t believe in the world you’ve created. You’re not convincing me. And questions of world-building are way more fruitful conversation topics than how far someone can walk in a hurricane. I ask that students push themselves—both in their reading and in discussion—beyond the surface, toward those underlying questions. I have gone as far as to ban the word “plausibility” (“likability” is another one) from workshop, as it is so often a euphemism for: “I sense there’s something going on here but I don’t have the language for it, so I’m saying this other thing instead.” Let’s help our students find the language.

The Call

The Call

The Call

by Yannick Murphy

Harper Perennial, 2011

240 pages / $14.99 Buy from Harper Perennial

Rating: 9.0

I picked this book off the shelf at the closing Borders based entirely on Yannick Murphy’s name, having been familiar with previous books, particularly Stories in Another Language, one of the Knopf titles under Lish. I decided to buy the book immediately after opening the book to its first page, and finding there the manner of deployment of information that appeared:

September 13th, 2011 / 12:06 pm

41 Endings: Cheever [with comment (mixed)]

I gave this to Ralphie and went home. [Only I didn’t say “Fudge”]

Then he went away, and, although the race was beginning, she saw instead the white snow and the wolves of Nascosta, the pack coming up the Via Cavour and crossing the piazza as if they were bent on some errand of that darkness that she knew to lie at the heart of life, and, remembering the cold on her skin and the whiteness of the snow and the stealth of the wolves, she wondered why the good God had opened up so many choices and made life so strange and diverse. [Pretty damn 19th century and pretty damn good. The next ‘experimental writer’ will actually write like Thomas Hardy]

She was always on the move, dreaming of bacon-lettuce-and-tomato sandwiches. [That’s very Brautigan, sir]

“I’m walking the dog,” I said cheerfully. There was no dog in sight, but they didn’t look. “Here, Toby! Here, Toby! Here, Toby! Good dog!” I called and off I went, whistling merrily in the dark. [I use this same tired move, only I say I’m “returning the movies.” A friend of mine “goes for donuts” and returns tired, with gin on her breath]

“Oh, we thought, signore,” he said, ‘that you were merely a poet.” [Like Yeats?]

The touchstone of their euphoria remained potent, and while Larry gave up the fire truck he could still be seen at the communion rail, the fifty-yard line, the 8:03, and the Chamber Music Club, and through the prudence and shrewdness of Helen’s broker they got richer and richer and lived happily, happily, happily, happily. [I got nothing. Excellent fucking ending line. That’s why you are you and I am me. Well done]

Then he put his head back on the pillow and died—indeed, these were his dying words, and the dying words, it seemed to me, of generations of storytellers, for how could this snowy and trumped-up pass, with its trio of travelers, hope to celebrate a world that lies spread out around us like a bewildering and stupendous dream? [Conrad? I hope a PhD is studying how long these ending sentences—dissertation, dis?]

Nothing less will get us past the armed sentry and over the mountainous border. [A bit Hemingway, but it’s cool, we all do that]

Dennis Cooper is interviewed in the new issue of the Paris Review (“I’m as interested by what sex can’t give you as by what it can.”)(as is Nicholson Baker)(as is a story by the rad Kerry Howley).

Utterance

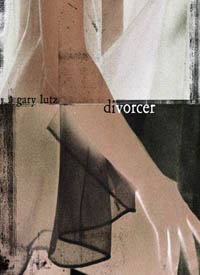

Divorcer

Divorcer

By Gary Lutz

Calamari Press, 2011

120 pages / $13 Buy from SPD

It’s no wonder that someone who might be said to live in the sentence would apply its logic—and its subversions—to his lens on the higher-order structures of life. In Divorcer, Gary Lutz tinkers with each level of human-linguistic interaction, cascading from social power structures, to family dynamics, personal relationships, full-scale utterances, isolated sentences, words, morphemes and phonemes, with an eye to at-once humorous and devastating exposure of the failures of empathy and failures of semantic coherence echoing throughout.

READ MORE >

September 12th, 2011 / 12:00 pm

Art’s a Fucking Mess

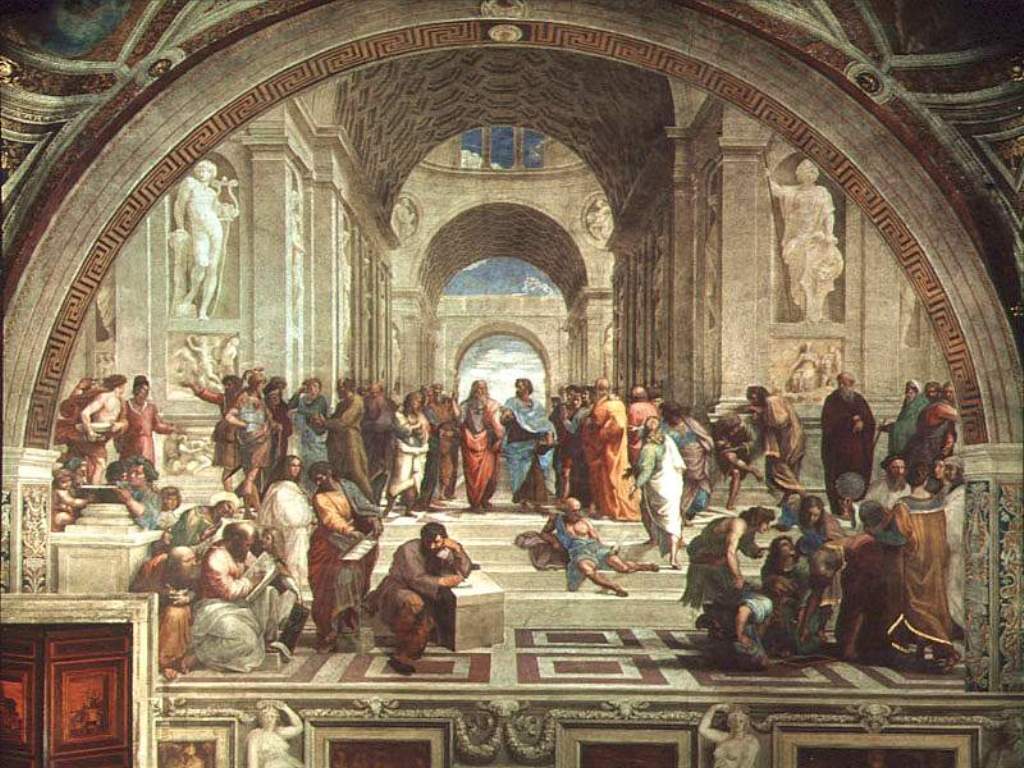

My friend Tadd over at Big Other has a post up about why Plato wanted to kick all the poets out of his ideal republic. And I’m no philosopher. But my understanding has long been that Plato’s problem with poets/art (besides the whole mimesis “copy of a copy” thing) is that art is messy, uncontrollable.

Like, consider this:

Someone—some artist somewhere—decided to make this. Is it good? Bad? Funny? Sick? Evil? Juvenile? Calculated? Hip? Clever? Stupid? Immoral? Amoral? Sure—it’s all those things, and more! It supports a variety of readings. In fact, the better an artwork is (I think this is a pretty OK one), the more irreducible it tends to be (at least, according to certain lines of aesthetic reasoning that I think Tadd would agree with).

Good art disrupts the social order. It wakes you up, shocks you, makes you feel alive—it makes you see the world again, differently. Bad art is boring, predictable, prescribed, a weak illustration of what you’ve already been thinking. (That’s my problem with so many depictions of September 11th, Roxanne—they reduce that day into something so digestible, so mundane, it’s as though it never happened.)

A follow-up to my last snippet post: What’s the “best” novel or story or poem or comic or song “about” September 11th? (Besides Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits).