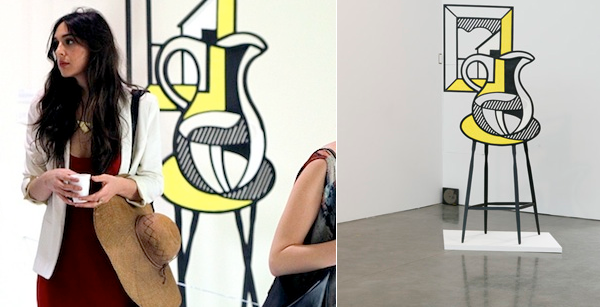

Still Life

As Claudia of Bravo’s Gallery Girls stood in front of a Roy Lichtenstein still life, the base on which the jug stood — a cut-out sculpture (technically) rendered as a flat painting and oriented in unison with its counterpart behind it — was cropped off, so that the average unacclimated viewer, blockaded online in two-dimensions, would have thought it was merely a painting. In this world of illusion, of collapsible iconic space, one may also be drawn to Claudia’s beauty, the sides of her hair as curtains to the constant one-act play of herself. One night after work, scanning through my Comcast options — with that kind of defeated shameful complicity in television viewing — I settled upon this show, skeptically, as it had appeared on some bitch’s facebook timeline. It basically follows half-a-dozen women through their lives as they maneuver New York City’s gallery world. We see effeminate attitudinal men in rimless spectacles, often holding obnoxious dogs; women whose countenances have been stretched both severe and eerily frozen by plastic surgeries; the glass spiderweb of a cracked iPhone being cried into, inside a cab whose fare their father is, well, faring. I may have shouted at the TV and lowered my pants. I may have drank a bottle of wine. “My still life paintings have none of those qualities, they just have pictures of certain things that are in a still life,” says Roy concerning his less than palpable work. Implicit satire is the spoiled child of the homage. In the episode I saw, Claudia got upset with soon-to-be ex-bff Chantal — whose distant Xanax induced gaze reminds me of a Nebraskan horizon one can never drive closer to — for supposedly getting sick in Paris, causing her to miss out on some hefty electricity bills. We then cut to commercial: a woman riding a bike with a tampon inside her, smiling as if ’twasn’t there. Perhaps menstruation is the opposite of God. We pretend it doesn’t exist. I felt sorry for myself, and the dead author whose novel I was neglecting. Later that night, some claws came out at a table adorned with tulips, its still life barely noticed in the background.

How do you revise, like literally, how do you do it: print and cut, type and delete, erase with an old school eraser, white out, etc.?

A Return to Candide

Candide

Candide

by Voltaire

Norton Critical Edition, 1991 / 224 pages Buy from Amazon ($11.56)

Penguin Classics, 1950 / 144 pages Buy from Amazon ($11)

I must have had g-rated goggles on when I first read Voltaire’s Candide because I didn’t remember how violently twisted the book got. Published as satire in 1759, it attacked Leibniz’s idea from his Monadology that this world was the best of all possible worlds. History intertwines with fiction in Candide as the backdrop of the Seven Years’ War and a deadly earthquake in Lisbon that killed more than fifty thousand people fueled Voltaire’s rage. The religious men of his age, the ‘optimists,’ tried to comfort people with the idea that everything, no matter how vile, happened for a greater good as it was driven by a higher power. Dr. Pangloss, Candide’s tutor and an obvious caricature of Leibniz, espouses this belief and Candide carries forward it as a conviction throughout much of the narrative. Voltaire drills in his rebuttal with the violent imagery of something straight out of a Takashi Miike film.

Take for example, Cunegonde, the love of Candide’s life, as she shares her tragic story:

As horrific as this sounds, shortly afterward, they meet an old woman who assures them her misfortunes outweigh theirs. She used to be a princess until her betrothed was poisoned through chocolate. She was then carried off as a slave:

October 5th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Slime Dynamics

Slime Dynamics

Slime Dynamics

by Ben Woodard

Zero Books, September 2012

84 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon

Ben Woodard’s SLIME DYNAMICS, recently released by Zero Books, offers a continuing exploration of subjects and modes of thinking developed over the last few years within the realm of philosophy that has donned the title of “speculative realism.” Woodard concerns himself primarily, both in this book and in his academic engagements, with the ideas of Dark Vitalism, which, as the book posits is

…the sickening realization of an inhospitable universe, stating that the production of life as an accidental event in time which is then contorted and bent by the banality of space, of our particular (and just as accidental) universal geometry and then further ravaged by accident, context, feedback and the degradation of wear and age.

Taking Dark Vitalism as its launching point Woodard continues to trace the idea of slime as “a viable physical and metaphysical object necessary to produce a eralist bio-philosophy void of anthrocentricity.” A turn away from anthromorphism, away from humanism perhaps, is another trade mark of developing thought, as it recenters the organicism of the world, the infinitude (outside of the phenomenological existence of human-beings–aka what came before Beings, what can come after, what this means). These continuing strands are carried throughout the short study in true continental style, vis a vis literary horror fiction, horror movies, video games and comics. This presents a fun context, at least for someone as genre obsessed as I am, to explore larger concepts.

While ultimately not utterly convincing in its case-studies, Woodard’s book does prove to be a fully engaging read and an interesting footnote on the development of speculative realism, specifically that of dark vitalism and the uncanny terror of the world carrying on without us.

October 4th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Death By Subtitle: How Extravagantly Fallacious Subtitles Are Ruining Books

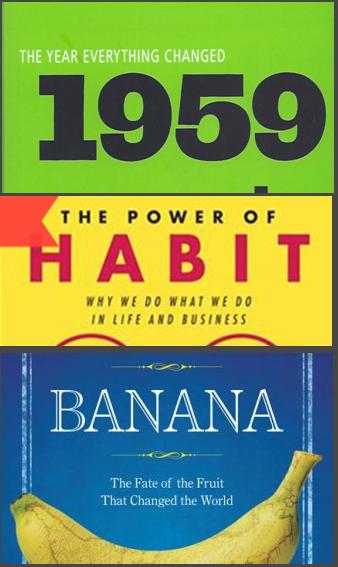

1959: The Year Everything Changed

Habit: Why We Do What We Do In Life

Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World

And now there’s Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How The World Become Modern, a book which, while very good, doesn’t live up to its subtitle. None of these books do. They can’t. Their subtitles are overly ambitious, promising that everything the reader has ever wondered about will be explicated in grand, enriching, yet academic detail over the course of the next 300 pages. Except this doesn’t happen and reader disappointment ensues. These books are all overpowered by their subtitles.

Greenblatt’s The Swerve is the history of a Latin poem, On the Nature of Things by Lucretius, which was lost ages ago and found in 1417. While Greenblatt’s love for this poem is clear and while he extols its greatness, he never comes close to explaining how the world becomes modern.

There are a few half-hearted attempts to justify the subtitle and a Malcolm Gladwell-esque idea that in history there are swerves, moments where everything suddenly shifts. (The key to having a Macolm Gladwell-esque idea involves capitalizing a noun then making it seem extremely important; luckily, Greenblatt has the dignity to avoid random noun capitalization.) Really, though, this book is the wonderfully well-researched history of Lucretius’s poem. It doesn’t have a lot to do with the entire world or momentous modernity. But if you’ve been keeping up with publishing trends, you probably already knew that.

Do you think it’s inappropriate to talk politics on HTMLGiant? Do you tell people who you’re voting for? Are there any honest Republicans out there willing to write a long ideological rant about Mitt Romney? (Please no liberals.)

DIED: Griffith Edwards

Griffith Edwards, Oxford-educated MD and addiction specialist, invented alcoholism. In 1976.

That is to say, he and a cowriter named Milton Gross first published a description of Alcohol Dependence Syndrome in the British Medical Journal in 1976, making the whole darn thing official.

Edwards spent his life considering, studying, talking about, writing about, and helping others with addictions.

*

ALCOHOL in HISTORY: Edited Highlights READ MORE >