Pasolini: Observations on the Long Take

I’ve been thinking about the cinematic long take a lot lately. I’ve always been obsessed with the long take. Among my favorite directors are Tarkovsky, Pasolini, Wong Kar Wai, Tsai Ming-liang. And lately I’ve been watching Bela Tarr on repeat. Like all his films over and over again, because I’m convinced that his use of the long take is accomplishing something very different than these other directors, a sort of reaching of a moment of clarity that results not in understanding but something else. Maybe something like the feeling of intimacy and claustrophobia and fear and relief that comes with giving a confession. Anyways, more thoughts on this coming soon. In the meanwhile, I wanted to post up Pasolini’s great essay on the long take. It framed a lot of thinking about the long take in film, what it means, etc. Sharing the essay with you below…

Werckmeister Harmonies dir. Bela Tarr

***

Observations on the Long Take

By Pier Paolo Pasolini

Translated by Norman MacAfee and Craig Owens

. . . .

Consider the short sixteen-millimeter film of Kennedy’s death. Shot by a spectator in the crowd, it is a long take, the most typical long take imaginable.

The spectator-cameraman did not, in fact, choose his camera angle; he simply filmed from where he happened to be, framing what he, not the lens, saw. [1]

Thus the typical long take is subjective.

In this, the only possible film of Kennedy’s death, all other points of view are missing: that of Kennedy and Jacqueline, that of the assassin himself and his accomplices, that of those with a better vantage point, and that of the police escorts, etc.

Suppose we had footage shot from all those points of view; what would we have? A series of long takes that would reproduce that moment simultaneously from various viewpoints, as it appeared, that is, to a series of subjectivities. Subjectivity is thus the maximum conceivable limit of any audiovisual technique. It is impossible to perceive reality as it happens if not from a single point of view, and this point of view is always that of a perceiving subject. This subject is always incarnate, because even if, in a fiction film, we choose an ideal and therefore abstract and nonnaturalistic point of view, it becomes realistic and ultimately naturalistic as soon as we place a camera and tape recorder there: the result will be seen and heard as if by a flesh-and-blood subject (that is, one with eyes and ears).

Dreams for Kurosawa/Raul Zurita (trans. Anna Deeny)/A View

Dreams for Kurosawa

Dreams for Kurosawa

by Raúl Zurita / translated by Anna Deeny

arrow as aarow , 2012

$10 Buy from arrow as aarow

I would like you to see how I’ve scratched and bent and battered this beautiful book. I have been holding this bark relatively near to my person for almost every day of the past few months. (I don’t go to the wheezy bar or to the co-op or to any grass just outside without some kind of bike bag growing out of my back. It rains on the way. There was an angry spill in August.) Do you think it’s still in a magical shape this way? I do. I thought I might want to write something about Raul Zurita when I got Dreams for Kurosawa in the mail, and I kept waiting for the bones of the poetry to dry out. They still haven’t. They drip on me. “Once again I see the worlds,” says a line in poem simply called #2 that I repeat to myself like tattoo berries.

Being near poetry means clanging mis-remembering and remembering together into brackish jewels. Both make the cardboard around us shine. In the case of Zurita, we have some kind of glimpse of where the lines between a real event and the logical leaps writing causes the brain to take exist. If you are familiar at all with the shapes that pus in and out of Zurita, you know he is a Chilean poet who writes primarily about surviving Augusto Pinochet’s atrocity-ridden coup d’etat in 1973. You know that his life is a circle of hinges burning around the real sadness it was pulped into. “I was seized by the Arauco brigade and before/dying I remembered the worlds” (#2). During the coup, Zurita was detained in the hold of a ship with a thousand others deemed enemies of the new military government. (He was carrying poems at the time, which were thrown into the water by a soldier. Those poems are his book, A Song for His Disappeared Love.) Over 30,000 people are estimated to have been tortured and a little over 3,000 killed during Pinochet’s time at the helm.

Being near poetry means clanging mis-remembering and remembering together into brackish jewels. Both make the cardboard around us shine. In the case of Zurita, we have some kind of glimpse of where the lines between a real event and the logical leaps writing causes the brain to take exist. If you are familiar at all with the shapes that pus in and out of Zurita, you know he is a Chilean poet who writes primarily about surviving Augusto Pinochet’s atrocity-ridden coup d’etat in 1973. You know that his life is a circle of hinges burning around the real sadness it was pulped into. “I was seized by the Arauco brigade and before/dying I remembered the worlds” (#2). During the coup, Zurita was detained in the hold of a ship with a thousand others deemed enemies of the new military government. (He was carrying poems at the time, which were thrown into the water by a soldier. Those poems are his book, A Song for His Disappeared Love.) Over 30,000 people are estimated to have been tortured and a little over 3,000 killed during Pinochet’s time at the helm.

November 2nd, 2012 / 12:00 pm

You Private Person: An Interview with Richard Chiem

I interviewed Richard Chiem on the occasion of his first book, You Private Person, published by Scrambler Books. Photos via Frances Dinger and (the above) Matthew Simmons.

What was your favorite book when you were younger? What books have made you lol or cry or feel excited?

I think I read a lot of Goosebumps books and Animorphs books, and I was trying to collect the whole series for each. If I think about 1995, there were many times of me just waiting by myself inside a Safeway, because you could find them in the book aisle. I could read one of those books in about two and a half hours, so it became an easy addiction, since I wanted to know everything, to know the whole story. I would stack up my stacks of books next to my video games and my comic books in towers. They were each numbered like episodes, and in different colors. It seemed perfect to me at the time to have them all. I would save up six or seven dollars, everything other week or so in 1995, waiting in line at a Safeway. I recognized a particular need to read. But they never made me cry or laugh. I don’t really remember what exactly I was feeling when I was eight years old, in third grade, but I remember those simple horror and adventure stories, and I can still talk about them.

I turn on subtitles when I watch movies now. Some of my friends hate it and some really like it. It was adding another dimension to every movie and it quickened the pace of the viewing experience for me. And I watch a lot of movies. I always write after watching

a movie when everything still feels really alive about the story.

Bourbakists for memory, unite! Jacques Roubaud’s MATHEMATICS: (a novel)

Mathematics: (a novel)

by Jacques Roubaud

Dalkey Archive, 2012

312 Pages, $14.95

Buy from Dalkey Archive or Amazon

Jacques Roubaud, a premiere intellectual force throughout the history, to some extent, of French letters, as they say, is primarily known to American readers as a member of the OuLiPo and a poet. Roubaud’s reach, however, spans far beyond these simple categorical realms, throughout his massive ouevre of work, much of which has actually be translated into English.

Mathematics:, while recalling ideas, perhaps, that come up in specific OuLiPian exercises, is not inherently an OuLiPian work, nor is it a work of poetry. The cover of the book, in Dalkey’s translation, presents the work as “a novel,” and to an extent, within the heterodoxical forms that a novel can take, it is indeed a novel, but in the bookstore-culture of American publishing, it would find a place more comfortable within that loose genre of the memoir, the autobiography, the academic term of ‘creative non-fiction.’

The book at hand is the third “branch,” as Roubaud himself calls them, of a larger project dealing with the issue of memory and also, really, Roubaud’s life. And Roubaud has had a full intellectual life, in his work and his academic career, his interactions with the French literati, his presence in the OuLiPo, his poetry and, as it turns out, his career in mathematics.

Copy on the back cover of the book presents the idea that Roubaud is one of the few writers who has successfully bridged the gap between left brain and right brain thinking, hyperbole to an extent because I would insist that there is not such a clear divide in the generation of texts, but there’s a literal application in Roubaud’s mathematics career, and how it’s affected his interactions with the OuLiPo. But, regardless, despite exploring the branch of his own life that is in tangent with his career in mathematics, this insistence is no more than a structural system for Roubaud to explore memory within this specific realm of his own personal history.

There’s nothing too exciting about the literal events that occur within this branch of Roubaud’s life if you’re not connected to a historical exploration of the development of mathematics, specifically in France, from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s. It is interesting to read about, but there’s nothing specific to launch onto–so really, the question is, what’s the draw to read 300 pages of Roubaud’s life as it connects with mathematics?

The answer is simple, and beyond any sort of right brain articulation–Roubaud writes with a pleasantry that moves swiftly, a story-teller of diversions, splitting his own history into the rhizome of existence, a refusal of a straight narrative, an abundance of (as Roubaud himself points out) non-essential details, simply the creation of a narrative space.

There is no explicitly beautiful language present, as it seems that Roubaud saves that for his more highly emotional works (the incredible beauty that’s present in some thing black, Roubaud’s book of poetry written after the death of his wife Alix Cleo Roubaud, is nowhere to be found here). Instead we move through the maze of memory, constructed within a labyrinthine Proustian totality. Roubaud addresses the reader throughout the work, explaining the project, offering his insistence on the work both as exercise and project, aiming towards, perhaps, an unspoken totality, but this is not the totality that Mallarmé was after with his notes toward le livre, rather this is just a re-articulation of a full life in the form of the book.

Roubaud himself being an interestingly detached character, the scenes that occur are both instantly understandable and curiously casual–in fact, Roubaud’s decision to arbitrarily move from poetry and language into mathematics is an understandable one: there’s this thought, perhaps, a thought that I share at least, that in some way mathematics offers an answer to all the questions we as writers have; mathematics offers a totality to these great ideas of life. None of us could say how, and even if we were to attain the level of higher mathematics required to understand the really heavy and earth-shattering proofs that have arose within mathematics throughout its continued development, the lever of pure abstraction wouldn’t offer any solace. But it’s a quantifiable goal, an idea that while maybe we won’t understand the answer, we’ll at least have it.

And through this there is hardly nothing present outside of Roubaud’s interactions with mathematics–there are tangents that arise, tangents of humanity, but only when they’re linked to the mathematical narrative, through people and places met and involved through classes, other professors, drinking soda in the army, reading treatises on algebra in the desert during the war, watching a woman always wait for the train at the same time; all of these things don’t add up to a point, they simple contribute to a life, life as a whole, as something imperfect and incomplete, as something that can be interesting exclusively in the way it’s told to someone else.

November 1st, 2012 / 8:55 pm

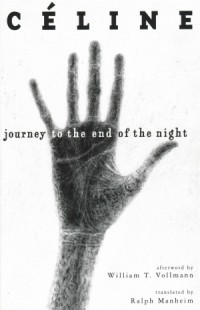

25 Points: Journey to the End of the Night

Journey to the End of the Night

Journey to the End of the Night

by Louis-Ferdinand Céline

New Directions, 2006

464 pages / $17.95 buy from New Directions

1. Will Self compared Joyce’s life before Ulysses to Céline’s experience in the war before writing Journey, in his exquisite discussion of the book upon some anniversary publication in The New York Times. I think I read that review about halfway through the novel and it complimented the thing quite well, gave a necessary contemporary slant on the whole thing.

2. Though remembered—much like Knut Hamsun—for his anti-Semitism (later in life) before his talents as an author after so many years gone by, a return to Céline and this novel in particular has occurred among authors and intellectuals almost every decade since its publication in 1932.

3. A new sort of manic transcription of the author’s experiences through his protagonist Ferdinand Bardamu jettisons the reader from war-torn France into the jungles of colonial Africa (my absolute favorite portion of any picaresque I’ve ever read) to post WWI America and back to France without missing a beat and yet the effect is akin to a hammer pounding against your chest.

4. I’ve read the book on three occasions, the last of which I suppose I felt ready enough and barreled through it in a couple of days and felt the aforementioned chest pounding that I’ve never experienced reading another book.

5. Its second translator, Ralph Manheim, also translated Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

6. Every time I remember that this is Céline’s first novel a little part of me that used to believe in writing as a career dies, then runs itself over in some hellish ghost tank, and dies again.

7. Famous for his use of three dots (“…”) in the sprawling paragraphs of his books, Céline—to me—has created a new and perfectly original way of de-Salinger-izing your first bildungsroman and turning it into a strange fucked up masterpiece.

8. Here we have the antihero, and the antihero’s doppelganger (in so many words) Robinson, who comes out of nowhere after any number of times to keep the protagonist company while he evades work, wanders around like a lunatic, and speculates about the desperate stupidity of mankind.

9. Bardamu’s a fan of kids, however; this being one of the few hopeful characteristics of the man. He believes in them, the promise of a good future, that maybe—just maybe—they won’t wind up shit like every adult he sees around.

10. The simplest characterization of this book is to say that it’s a picaresque, which is valid, but feels like the largest slight inflicted upon a great work of literature since everyone said all that shit that one time about your favorite whoever the hell; so I don’t want to do that. I want to call it a bible for people with less-than-hope but more-than-pettiness who hope to suck the congealed blood from the wounds of a better life forgone in the name of money, or democracy, or the nuclear family; and those who read it needing that companionship, needing that sense that all is not lost just yet, you’ll find it here. READ MORE >

November 1st, 2012 / 12:09 pm