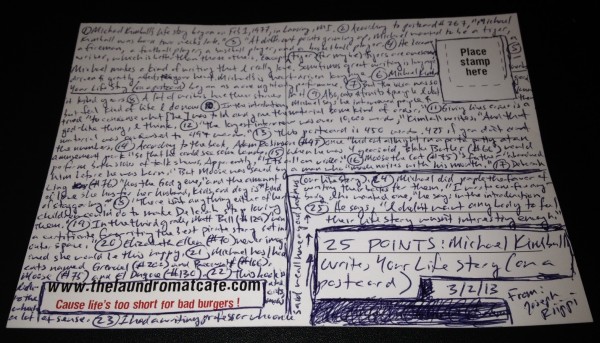

25 Points: Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (on a postcard)

Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (on a postcard)

Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (on a postcard)

by Michael Kimball

Mud Luscious Press, 2013

162 pages / $15.00 buy from SPD or Amazon

March 21st, 2013 / 12:09 pm

In case you’ve missed it, Kent Johnson’s gone after Marjorie Perloff (PDF) for her entry on “Avant-Garde Poetics” in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 4th ed. Writes Johnson:

[With] exception of a passing reference to the Brazilian brothers Augusto and Haroldo de Campos and their Concretista moment, not a single poet or group outside the Anglo-American/European experience is acknowledged. The entire Iberian Peninsula, even, goes missing!

Among those missing, he argues, are Vicente Huidobro, César Vallejo, Aimé Césaire, Kitasono Katue, Alejandra Pizarnik, and Raúl Zurita—plus he takes a few swipes at Conceptual Poetry and Flarf. Well worth reading.

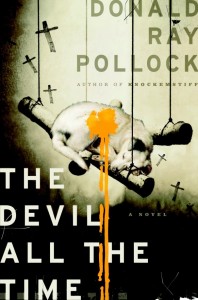

An Interview With Donald Ray Pollock

Several years ago I was about to board a plane to Virginia where I was to explore the campus of a school that would teach me to become a mortician. It’s since become a joke in various places that ‘I’m here, because my job as a mortician fell through…’ etc. Before boarding the plane, I grabbed a magazine—my memory eludes me as to which magazine it was, some cultural blah blah blah; something where books are mentioned—and during the two or so hour ride I read most of the magazine, finally rereading one portion over and over again.

Several years ago I was about to board a plane to Virginia where I was to explore the campus of a school that would teach me to become a mortician. It’s since become a joke in various places that ‘I’m here, because my job as a mortician fell through…’ etc. Before boarding the plane, I grabbed a magazine—my memory eludes me as to which magazine it was, some cultural blah blah blah; something where books are mentioned—and during the two or so hour ride I read most of the magazine, finally rereading one portion over and over again.

It was a blurb written about a novel called The Devil All the Time, with corresponding cover art featuring mangled marker-drawn crosses and skulls; and a glowing review from somebody somewhere. The writer’s name was Donald Ray Pollock, a name most people recognize along with the titles of his books nowadays.

Again, didn’t wind up becoming a mortician, but on that trip I stopped at a bookstore and picked up a copy of Pollock’s second book, reading it from cover-to-cover on the plane and car ride back to the middle of nowhere in Wisconsin; and for the first time in a long while I started to find romantic little moments along the barren roads beside our car, having Pollock’s eyes to see that you didn’t need New York to have literature, I guess, that sort of thing.

A month or so later I was cursing myself, finding out that Pollock’s first book, Knockemstiff, was sort of a prerequisite for the second—set as they both are in similar vistas of rural Ohio, where everything reeks of old death and strange blood. I picked up a paperback copy of his first as soon as I could and immediately set to reading it.

Both times, in similar and yet subtly different ways, I was floored. Knockemstiff reads as if Raymond Carver and Dennis Cooper had a kid and he lived down the street from Scott McClanahan; gloriously fucked-up images balanced against the monotony and odd sense of peace you get when you’re so far off the radar that you forget it even exists. This is Pollock’s coming out into the world of literature, and he does so with no shit-covered stone unturned. With his second, The Devil All the Time, it could be said that Pollock prolonged the sting of his previous short stories and the result is a portrait of American life nearly impossible to forget. The book opens with a father and son walking out to a small grove where they’ve been sacrificing animals, hoping for some kind of good fortune, and from then on it barrels headlong into a story spanning many years and veering off into these dirty cinematic takes on growing up, dealing with death, and out-and-out crime.

Fou Magazine came back from the dead. Check out their 4th issue here. They also have a twitter account.

25 Points: The Man Who Noticed Everything [UPDATED]

The Man Who Noticed Everything

The Man Who Noticed Everything

by Adrian Van Young

Black Lawrence Press, 2013

200 pages / $16.00 buy from Black Lawrence Press

[Update]”The Sub-Leaser,” discussed here, is now available to read in Electric Literature’s “Recommended Reading” [End Update]

1. I first met Adrian Van Young at 2012 AWP, when he was hanging out at the Gigantic table. I remembered him as an engaging person to talk to. That’s saying a lot, cuz, you know, AWP.

2. Six months later he emailed me about reading in Baltimore. That’s when I remembered what a nice guy he was.

3. His email was cordial but also professional, and he attached a press release about his book, The Man Who Noticed Everything, and a headshot. The color scheme in the photo matched the colors on his book jacket: black and dark green.

4. Ben Marcus said “you’d think this book was an anthology collecting the work of the best young writers of the new generation”—talking about The Man Who Noticed Everything.

5. So we set up a reading for January, even though I hadn’t read his book and even though the main provision for the series that Stephanie Barber and I run is that we’ll only host writers whose work we really admire. I guess the thinking was, this guy has his act together.

6. And he does. I’m not just saying that because he brought a fresh bottle of Jameson to the reading.

7. At the reading, Adrian read a short story. Sometimes I have a hard time listening to fiction. It can be so boring.

8. But while Adrian read, I laughed and laughed. The story was called “The Sub-Leaser,” and listening to it, I felt like it was full of jokes. Or, actually, it struck me as a better kind of funny writing, in which there aren’t actually jokes, but the whole concept (and the way the concept is delivered) is meant to be funny.

9. What’s more, the funniness happens within the prose, which is primarily descriptive, and that is a really hard and precarious thing to do. The story’s narrator is describing his apartment. He says, “My apartment is a standard one for the part of the city where I live. It begins at the door, which opens, like so, to show the splintered wooden hallway that I mentioned before. On the right is a bathroom, ill-sequenced of tile, with a sink built onto the wall and a bathtub, where a thin and mildewed curtain hangs, clad in a pattern of green and white plaid. To the left of the curtain, an insolent toilet, coated with a film of brown.”

10. “ill-sequenced of tile”? “an insolent toilet”? You see what I mean. The whole story is like that. READ MORE >

March 19th, 2013 / 11:09 am

A Mountain City of Toad Splendor by Megan McShea

Yeah but come on, that’s the title of a book right there.

As Blake put it, it’s as if Megan studied at the Harvard for Ooh, and as Jeff Jackson said nicely, “You’re never sure what’s around the next comma.”

Lucy Corin said she remembers Megan’s dreams as if they were her own.

This book comes out today. It’s poetry and microfiction. It’s just $9 at PGP. And there are videos about it. Cool.

March 19th, 2013 / 8:37 am

My Last-Ever AWP Apology

Unlike some other stuffed animals, I had a very good time in Boston. Admittedly, that’s probably because I didn’t get there until Friday. I also tried to avoid any and all conversations that had to do with books. The only time I talked about writing was when my buddy Mike and I drunkenly explained “epistemology ” to our non-MFA friends. Gross.

The two coolest stuffed animals I met there were Tyler Gobble and Layne Ransom. We probably hung out for a total of 25 minutes, but it was a real dope 25 minutes: we played dice and Tweeted from each other’s phones and hopped around on a dance floor that was pulsating. I always leave AWP with a swollen, stupid heart because of all those instances where internet user names morph into actual people. Meeting these two actual people was definitely one of my most swollen moments (ew).

But all that said, I have to apologize to Layne. Because I did something stupid.

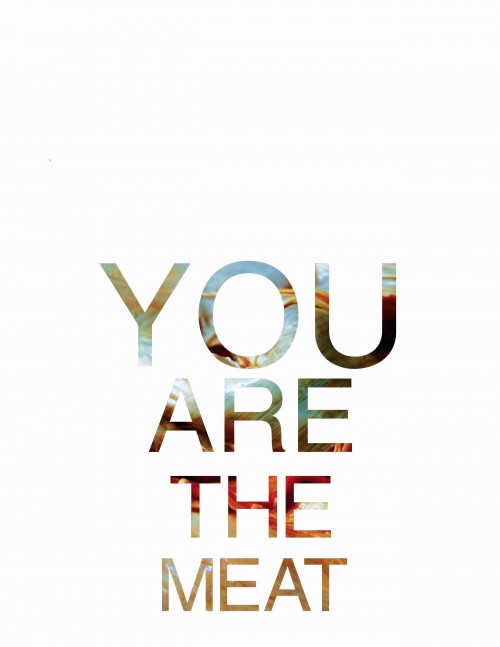

The week before AWP, I had bookmarked about ten new online lit journals and chapbooks, because AWP was coming up and OMGWTF I had so many travel-sized tubes of toothpaste to buy. The last thing I wanted to do was virtually thumb through lit shit, but then someone posted a link to You Are The Meat (Layne’s new jumpoff from H_NG_MAN Books) right when I was about to eat some Chinese food. The Chinese food was disgusting; You Are The Meat was anything but. I was completely captivated by each of the fourteen poems in this digital chapbook (which you can download for free, BTW). Layne’s writing is like the dude you always want to invite to your dance party—these poems are going to hug you for twenty seconds too long, drink all the empties in your recycling bin, and pick a drunken fight with the choad who accidentally says something sexist. Then, in the morning—when you’re really hung over and want to do nothing but eat some eggs—they’re going to say something silly and beautiful that will remind you of how nice it is to be around good, good people. READ MORE >

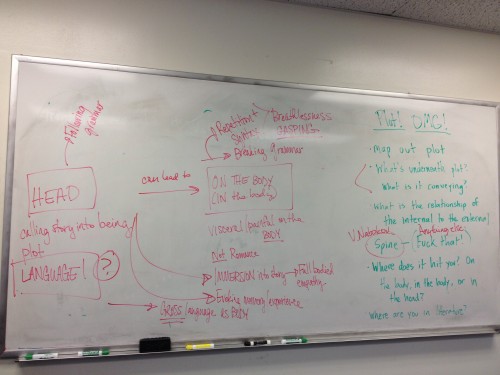

in which Lily teaches a class on a whiteboard

This is what happened in my grad Form & Technique in Fiction class today:

Here is how it happened. Every Wednesday, students read articles and essays that are NOT fiction. Last class, they read & we discussed a unit I called “The Human Body,” which included the following texts: Dong et al, “Unilateral Deep Brain Stimulation of the Right Globus Pallidus Internus in Patients with Tourette’s Syndrome”

(from The Journal of International Medicine); Grahek, Feeling Pain and Being in Pain, “Ch. 1: The Biological Function & Importance of Pain”; Ramachandran, Tell-Tale Brain, “Ch. 3: Loud Colors and Hot Babes: Synesthesia”; and

Scarry, The Body in Pain, “Ch.3: Pain and Imagining.”

Here is how it happened. Every Wednesday, students read articles and essays that are NOT fiction. Last class, they read & we discussed a unit I called “The Human Body,” which included the following texts: Dong et al, “Unilateral Deep Brain Stimulation of the Right Globus Pallidus Internus in Patients with Tourette’s Syndrome”

(from The Journal of International Medicine); Grahek, Feeling Pain and Being in Pain, “Ch. 1: The Biological Function & Importance of Pain”; Ramachandran, Tell-Tale Brain, “Ch. 3: Loud Colors and Hot Babes: Synesthesia”; and

Scarry, The Body in Pain, “Ch.3: Pain and Imagining.”

My Pet Serial Killer by Michael Seidlinger

My Pet Serial Killer

My Pet Serial Killer

by Michael Seidlinger

Enigmatic Ink, 2013

312 pages / $13.99 Buy from Amazon

Some people raise cats and dogs. Claire, the protagonist of Michael Seidlinger’s My Pet Serial Killer, raises serial killers. Caged within the pages of the book is the ‘Gentlemen Killer,’ his gallery of helpless women, and a whole panoply of cultural idiosyncrasies that seem strangely alien when viewed through the cool detachment of Claire. Claire is an experienced collector who dissects social rituals with the vivifying apathy of a biologist. I’ve read a lot of serial killer books in the past two years, most trying to differentiate themselves by latching onto a more unusual gimmick. My Pet Serial Killer distinguishes itself with a unique foray into the world of mass murderers that’s best encapsulated by Claire’s proposition to the Gentlemen Killer: “I support you financially. I give you a place to hide. I make sure you are never under suspicion of being what you really are, a cold-blooded psychotic killer (so hot), and, in return, you clue me into your process. You become mine.”

The prose flows in a conversational rhythm and her tone remains relatively level throughout, despite the fact that she is describing horrific scenes of murder. The macabre episodes are lent an especially disturbing tone because of the way Claire chastises her pet for not carrying out the murders in an optimal way. She treats him like a puppy gone awry and complains about him like an unruly boyfriend: “He doesn’t want instruction but, as master, I feel like I need to show him how it’s supposed to be done. He’s too lenient on method and MO. No wonder we find ourselves needing to find patsies covering our tracks every few girls.”

Interspersed within the narrative are italicized segments that are described as “optional” but provide deeper insight into the issues at stake and break apart traditional relationships. Targeted are friendships, classmates, strangers at parties, lovers, master and pet, and even reader and author. Claire refuses to reveal her name to Victor, AKA the Gentlemen Killer, who is a suave and dashing man that can woo almost any woman into bed. She’s less impressed by him, especially after her initial exhilaration dies down: “I’m quickly discovering he’s not much of a talker after he’s exhausted all introductions and quick casual lines. Everything’s practiced until he’s out of memorized and rehearsed material. He’s awkward at his most pure, and he’s incapable of matching my gaze when I’m still there looking for more… So I’m the one that has to tell him what to do. I’m telling him to go into his room.”

March 18th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

25 Points: Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation”

“The Silence” (still), directed by Ingmar Bergman (1963)

[Update: I posted a follow-up to this post, here.]

1.

Susan Sontag’s seminal mid-60s essay has come up several times at this site. I’ve been busy rereading it since Xmas, and want to take this chance to set down some thoughts regarding it.

2.

Obviously, whatever interpretation is, Sontag seems against it.

3.

What, then, does Sontag mean by “interpretation”? Does she mean any and all interpretation, as my fellow contributor Chris Higgs recently argued? Or something else, something more specific?