fun camp blooper negation

Seven days ago HTMLGIANT received an anonymous review submission for Fun Camp by Gabe Durham. An anonymous review went live today around noon. However, the review had to be taken down today a little after five. Sometimes you get an email at 8:04 AM and then another at 8:08 AM and you just read the one from 8:04 AM and then that causes a blooper. This is perhaps irrelevant to the following:

DAVID LYNCH’S DESTABILISING AFFECT

GOOD DAY TODAY: David Lynch Destabilises the Spectator

GOOD DAY TODAY: David Lynch Destabilises the Spectator

By Daniel Neofetou

Zero Books, 2012

93 Pages, $14.95 (buy it at Amazon)

The initial conceit of Neofetou’s Good Day Today is one that I inherently agree with, and one that I think should be considered in larger terms of not only film studies, but an understanding of how to watch movies in general. As a theoretical construct it was first introduced to me in Cinema and Sensation: French Film and the Art of Transgression by Martine Beugnet, a brilliant study of affect found in the mileu of the “new french extremity,” the art house mavericks Bruno Dumont, Philippe Grandrieux, Catherine Breillet, and so on. While Beugnet’s book does lose itself to a final chapter devoted to a Deleuzean study of film & embodiment that, in my opinion, adds nothing to the first two-thirds of the study, overall the book presents and articulates, with careful, pointed examples, what cinema can do for the spectator.

Neofetou’s book, while seemingly not indebted to Beugnet’s book at all (something that I would argue is, in a sense, unfortunate) takes certain theories that have formerly been applied only to experimental (non-narrative) cinema, and looks at David Lynch’s films within this context. His thesis is that these modes of cinema, particularly within the diegetic sway of a narrative & representational film, serve to–as the title would suggest– destabilise, disorient the spectator, the viewer of the film. As such, the book offers a very close reading of a number of Lynch’s films–though the titles of note are, of course, Inland Empire, Lost Highway & Mulholland Drive–& the scenes therein, showing the reader just exactly how Lynch manages to simultaneously play with affect while still insisting upon the “rules” of narrative/figurative/”realist” cinema to the point where when the rules are broken, we are destabilised not because said scene doesn’t make “sense,” but because the scene violates the inherent logic of the film & undermines the authority of an omniscient narrative position.

And the book does this well. Neofetou, throughout the book, takes examples from a number of canonical experimental films (Meshes of the Afternoon, Flaming Creatures, Gidal’s Epilogue) and compares their techniques to the techniques of certain scenes found in Lynch’s films, highlighting both the similarities between the scenes & the differences that arise out of the context of the films as a whole. There’s also a brilliant chapter near the end of the book dedicated to the idea of Lynch’s use of pop-music, absent dialog, and sound, that is a great chapter in its own capacity in looking at the way audio works toward the viewer in a cinematic exegesis.

Another strong point of the book is that within his examination of Lynch as a filmmaker who works with affect more than representation, Neofetou does an excellent job of both rejecting and explaining this rejection of the idea that Lynch’s films are “puzzles” to be solved–closed films where there is a literal solution. This, of course, is ridiculous, and a repeated mode of viewing that I personally find insufferable because, as Neofetou points out that Sontag mentions in her essay Against Interpretation, this mode of viewing “blinds [the spectator] to the work’s sensual facets”.

The book is not perfect, however, and there are two major faults that certainly don’t kill the book, but strike me as perhaps frustrating. The first being a short 7 page look at Lynch’s films through the eyes of the ‘Bechdel Test,’ ultimately considering accusations of Lynch’s films as misogynistic. Unfortunately the chapter ends up sounding apologetic instead of actually engaging with the idea, as its idea loses itself in a self-aware politically correct feedback loop that undermines any sort of look, thus rendering the chapter as blank space in terms of critical thought. I’m curious as to its place in the book, as there are repeated comments regarding Lynch’s ostensible a-political stance.

Which, in a way, leads to my other complaints–the subtitle of the book, the copy on the back, leads one to believe that after introducing (& proving) the idea that Lynch destabilises the spectator, there is little suggested beyond this in the text itself. There are a lot of directions that this could be taken, and the copy suggests that the book will take this idea in the direction that it helps to shake the politically hegemonic mode of representation, which helps to destabilise the idea of binary, simplicity, homogeneity.

April 30th, 2013 / 3:58 pm

The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson

The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson

The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson

by Bryan Furuness

Black Lawrence Press, March 2013

309 pages / $18 Buy from SPD or Black Lawrence Press

Bryan Furuness’s first novel, just out from Black Lawrence Press, takes on taboo territory – both the taboos of polite society (parental separation, suicide, rape, incest, abortion), and the taboos of impolite contemporary fiction (namely, Jesus). By which I mean Jesus as a good guy, Jesus as possibly ourlordandsavior. The volatile tension that results when you mix the unspeakable with the overspoken complicates what could otherwise be a well-written but conventional coming-of-age novel. Its subtle moralizing threatens didacticism but is consistently surprising and complex enough that it will at least goad readers into remembering how daunting it was as child to observe so much of the adult world invested in the Bible – a kid’s story of good and evil, impetuous gods and walking dead.

I was first introduced to Furuness – and to Revie Bryson – in a story called “Ballgrabber” that appeared in Hobart 9. Revie surveyed the world of kids in such an irreverent, fresh, hilarious way that I filed Furuness’s name away and vowed to read his first novel whenever it came out. I read Lost Episodes in three days, and that same irreverent freshness was there to remind me why I’d been anxiously awaiting its release.

The book opens with Revie believing that, on his twelfth birthday, God will reveal that he is, in fact, the second coming of Christ. As Revie begs his father to take off work and be there for the big event, Furuness riffs on a quote from the Gospels that lingers somewhere in many of our minds: “I needed him there when the big voice came from the sky, declaring me His son, with whom he is really excited to be working” (24). Revie’s mother, whose Hollywood dreams were dashed by early motherhood, departs early in the novel for a last-ditch pilgrimage to La-La Land, leaving Revie and his father back in Indiana, feeling – I love this – “awful and tender” (107). The family’s brokenness brings out the worst in everyone: Mom’s pathetic optimism, Dad’s inability to handle the most meager domestic duties, and Revie’s devastating speculations, such as: “Our family was the toxin my parents were trying to flush from their systems” (130).

As with any novel that takes risks, this book is vulnerable to some heavy questions. Why do our estranged parents finally have makeup sex right after discussing their son’s sexual activity? Are they getting off on it? Why do Revie’s clothes need to come off as a peripheral character steps up to deliver the novel’s main moral crux? Part of me wants to tap the side of my nose and suggest we should give kid nudity and catechism class a bit of distance, but a greater part of me applauds this book’s exploration of daunting life circumstances we normally hide behind euphemisms like “messy terrain.” I’d rather a novel raise problematic questions than just answer comfortable ones.

April 29th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Another way to generate text #7: Gysin & Burroughs vs. Tristan Tzara

A while back, I ran a little series, “Another way to generate text.” The first one proved fairly popular, and I’ve been meaning to make more of them, but generative techniques haven’t been on my mind. However, my post last week, “Experimental fiction as principle and as genre,” generated a lot of text (haha), in the form of comments. Some people who chimed in questioned whether the Cut-Up Technique that Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs developed and used in the 1950s was ever all that experimental. Specifically, PedestrianX wrote:

I find it hard to accept this argument when its main example, the Cut-up, didn’t start when you’re claiming it did. I’m sure you know Tzara was doing it in the 20s, and Burroughs himself has pointed to predecessors like “The Waste Land.” Eliot may not have been literally cutting and pasting, but Tzara was.

This comment got me thinking about the role influence plays in experimentation; more about that next week. Today I want to address the point PedestrianX is making, as it strikes me as pretty interesting. Were Gysin and Burroughs merely repeating Tzara? Or were they doing something substantially different?

To figure that out, I decided to run through the respective techniques, documenting what happened along the way. Because if I’ve learned anything in my studies of experimental art, it’s that thinking about the techniques is usually no substitute for sitting down and getting one’s hands dirty.

If you want to get dirty, too, then kindly join me after the jump . . .

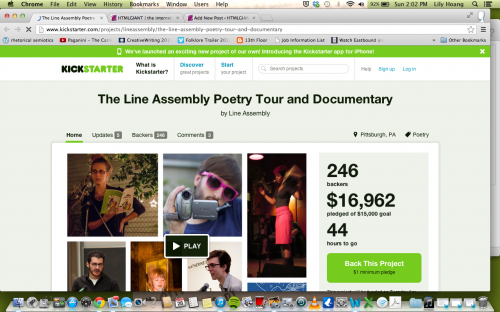

Support POETRY now

Got some dollar dollar bills? Support six kicking poets kick it through the US.

The Line Assembly Poetry Tour and Documentary might even be coming to a city near you.

I love them. You should too.

Late work

One wonders if the staff of Dunder Mifflin ever saw the late Monet waterlilies painting, a print at least, framed in the conference room as a kind of covert bourgeois window through which one might mentally escape to softer times, whose chubby mascot was a man slowly taken by cataracts, whose artistic vision was no doubt clearer than his literal one. French impressionist (and, to a degree, Pop Art and Abstract Expressionist) prints are mainly used in corporate settings to placate the employee, condescendingly, as if all they needed to be happy was something pretty to stare at, when in fact it only implicates the dissonance between surrendered office life and the more vigorous ideals of artistic inquiry. I’ve always found the late Monet print an odd, yet provocative, choice. Perhaps the set designers wanted something deep behind the shallowness of Michael Scott. As The Office plays out its final season, we may be left with some more inadvertent metaphors: the casting politics of who would play the boss, and the legacy of an unstable company, who in a realist market would have been eaten alive by more faceless competitors Office Depot and Office Max; the sweet courtship and eventual nuptials of Jim and Pam, whose subsequent boredom of each other seemed to ooze from the actors without acting; the rogue zen of Stanley Hudson, who solved 10,000 crossword puzzles in what were likely out-of-body experiences; the increasingly comical scenarios less probable, obsolete after the novelty of the ironic “fourth wall nod” wore thin. Most compelling were the accurate personnel departments (e.g. Accounting, Office Relations, Sales, Human Resources, Executive, Warehouse, Production) ascribed to each character, whose demeanor and actions held consistent with them. Such vocational intricacy had, in the past with other shows, been simply consolidated as an abstract “job” to which someone went when they weren’t on the main stage, that is, home. The Office took the family away from home, into their own personal world of laughter and resent. Monet, the more successful of the French impressionists, built Giverny garden for the sole purpose of having a final chronic subject to paint until his death; he painted around two-hundred-and-fifty waterlilies, whose muddled canvases, thick and opaque, wore the transparent mask of a lake’s surface barely there. At its best, art is the profound realization of the invisible. Imagine a half-blind man — who famously declined ophthalmological help in aid of his abstractions — squeezing out more and more purple like an inside bruise finally surfacing, each work darker and darker, as if to trace the slow yet unwavering arc of an hourhand as it approaches night.

SOME BOOKS THAT I’VE RECENTLY ACQUIRED THAT I ‘M REALLY EXCITED ABOUT.

***

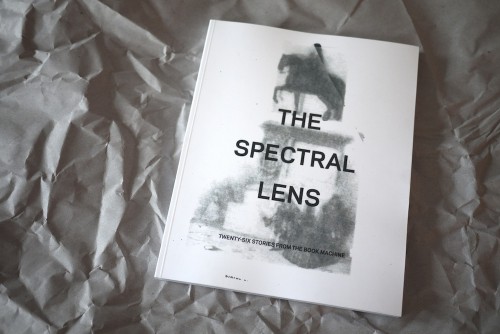

The Spectral Lens & Apparition of a distance, however near it may be by Paul Soulellis

I met & discovered the work of Paul Soulellis at the recent LA Art Book Fair and got super excited right away.

As taken from his website (as are the photos above):

The Spectral Lens (Twenty-Six Stories from the Book Machine) (2012) is a visual poem featuring images photographed by Google book scanners through tissue paper. The scanner treats the tissue paper as a “valid” page in the book and scans it as it would any page, capturing the image (or text) behind it. The images are degraded in various ways, depending on the texture and opacity of the vellum. Rips or folds in the tissue are sometimes captured.

The images are “mistakes”—visual information that might normally be corrected or removed by bots. Instead, the errors remain as permanent additions to the Google Books library, forever altering the viewer’s perception of the work.

I search for these mistakes and treat them as found photography. My screencaptures expose deviations in the algorithms hiding deep within the archive.

The Spectral Lens is at once the glass eye of the book machine and its faceless human operator; it is also the lens-less “camera” of my computer.

I was immediately struck by the haunting simplicity of these images, that such a strange and technological process could aid in creating such immediate & subtle emotional works.

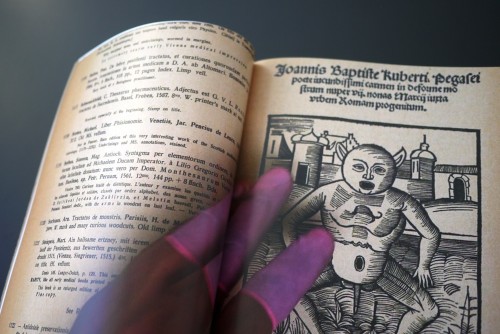

His other project, though similar in technological source looks at a different sort of glitch. Also from his website:

Apparition of a distance, however near it may be (2013) is a collection of found images portraying Google Books employees physically interacting with books inside the digital space of the book scanner, gathered into a 42-page print-on-demand publication.

As accidental recordings, the images mistakenly add human physicality, movement and distortion to the experience of consuming the static book in a browser window. These anomalies are usually corrected or removed by bots, but sometimes the errors remain, becoming spectral additions to the Google Books library and permanently altering the viewer’s perception of the content.

Here the images aren’t haunting, but slightly unsettling and creepy. Something about the lingering, partially-gloved hand that adds a strange layer to the usually austere realm of Google Books.

April 26th, 2013 / 2:46 pm

Consider supporting Kindergarde Anthology for Children

This is the first time I’ve ever donated to a Kickstarter project, because this is the first one that really compelled me to participate. Check out their project page to see a video of kids reading poems from the anthology and talking about the avant-garde, and then consider joining me in donating to this worthwhile project:

Black Radish Books is proud to present KINDERGARDE: Avant-garde Poems, Plays, Stories, and Songs for Children, an award-winning anthology that features 85 experimental writers from across the country, including: Anne Waldman, Beverly Dahlen, CA Conrad, Christian Bök, Douglas Kearney, Eileen Myles, Etel Adnan, giovanni singleton, Harryette Mullen, Joan Retallack, Johanna Drucker, Juan Felipe Herrera, Julie Patton, Kenny Goldsmith, Kevin Killian, Leslie Scalapino, Lyn Hejinian, M. NourbeSe Philip, Noelle Kocot, Robin Blaser, Rosmarie Waldrop, Sawako Nakayasu, Vanessa Place, Wanda Coleman, and many others!

Our goal is to make the book as widely accessible to kids as possible. And since we are an independent, collective press, we need additional support to fund this project thoroughly. We’re hoping that 100 people will purchase books through this Kickstarter campaign so we can fully fund a large print run of the KINDERGARDE anthology.

The KINDERGARDE project helps kids know that there are many ways to think and be in the world and that their ideas are important — no matter how different or “strange” they may seem. By supporting this project, you are expanding kids’ ideas about what literature can be and do. And you are also supporting creative risk-taking and open-mindedness. Join us!

I DON’T “GET” POETRY READINGS

I’m a soon-to-be graduate of an M.F.A. program in creative writing. All I have left to do is teach a few classes, defend my thesis, and read a few books. Oh. And I’ve also been tasked to write a report on a poetry reading. This last point is why I’m writing to you now.

Let me backtrack for a moment though to tell you that before I was an M.F.A. student, I was an undergraduate working my way towards a B.A. in creative writing and a B.S. in advertising. Before that, I was a teenager that lived with my father, who was a professor, and my mother, who was an English major. My mother took her major very seriously, and as a result I began reading Poe, Melville, Plath, Tennyson, and other “canonical” writers at a very young age.

In short, I’m no stranger to poetry.

However, after going to the Hoa Nguyen reading at the University of Colorado at Boulder on February 21st, I realized that I don’t really “get” poetry. Or rather, I kind of “get” poetry, as much as it’s possible to be “gotten,” but I don’t “get” poetry readings.

After the reading, I confronted a friend about my dilemma: having to write a piece on something I don’t really understand. He recommended I read the VICE article by Glen Coco titled: “I Don’t ‘Get’ Art.” I ripped off the title, but what choice did I have when Coco said it so well the first time? Coco’s title is modest. It blames no one but Coco himself for his inability to “get” art.

There are others, however, who are more hostile towards poetry and its various, associated artifacts.

With the whole Lena Dunham Girls craze sweeping the nation, I thought I’d watch her film, Tiny Furniture. What particularly stuck out to me about the film was a statement one of the characters made about poetry. It went, “Poetry is a very stupid thing to be good at. Poems are basically like dreams–something that everybody likes to tell other people but nobody actually cares about when it’s not their own. Which is why poetry is a failure of the intellectual community.”

April 26th, 2013 / 12:00 pm